How 'The Journey' Anime Film Brought Saudi Stories To Life

The Japanese style of animation known as anime is underpinned with narratives of community, loyalty and collective purpose. Its ubiquity feeds a growing appetite for the art form, becoming popular in the Middle East.

In 2018, on an upper floor of a modest office building in the Nakano district of western Tokyo, Mohammed Aldhafeeri adjusted his traditional Arab shamagh headdress and prepared to go into battle.

The building was the headquarters of Toei Animation, one of Japan’s oldest and best-known animated-film-production companies.

Toei staffers watched enthralled as Aldhafeeri squared up to his brother, who was similarly dressed in a thawb — a men’s ankle-length robe, tucked in at the waist — and armed with a carefully designed cardboard sword. Cameras recorded the “battle,” as the two men exchanged good-natured blows.

“We were models,” says Aldhafeeri, now 38, a concept artist born and raised in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, who lived and worked 12 years in Japan. He explains how his Japanese colleagues were tasked with animating a battle scene from ancient Arabia. But they were falling short with their lack of firsthand historical knowledge.

They needed to see how a shamagh wrapped around the head, how the fabric of a thawb moved in the air, how a traditional Arabian sword differed from more familiar Japanese weapons.

Aldhafeeri explains that he tailored costumes himself and brought them to the office to wear in front of his colleagues, so they could study them and touch them, and also created weapons and other cultural artifacts to be as authentic as possible. “In the end, we broke both swords—it was a long fight!” he laughs.

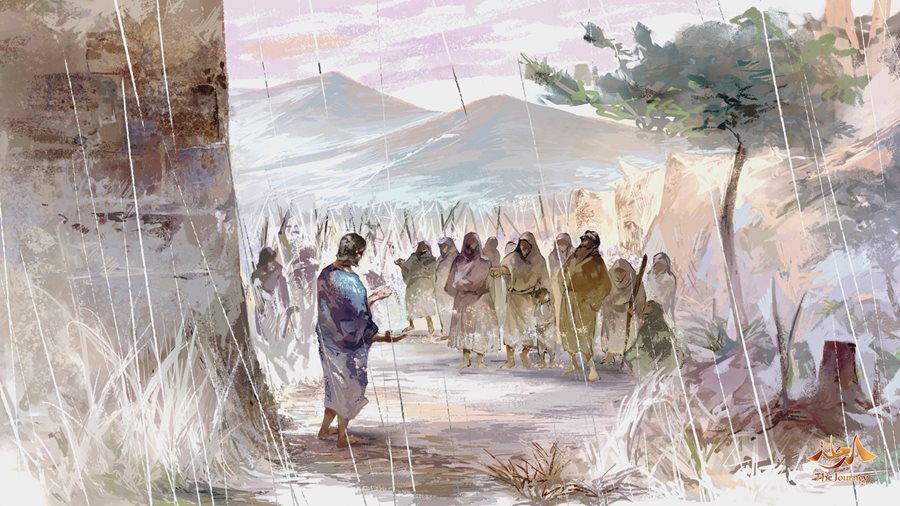

The battle scene formed part of The Journey, a unique co-production between Japan and Saudi Arabia in the burgeoning field of animated movies, or “anime” (AN-ee-may). This distinctively Japanese style of animation is often characterized by bright colors, flat backdrops and complex, dramatic storylines. As in manga—a related Japanese art form whose medium includes printed graphic novels and comic books—characters are drawn with bold lines and oversized, expressive eyes, displaying strong emotions through a range of stock facial expressions and body movements. Community, loyalty and collective purpose underpin many narratives, and the lone superhero figure of American comic books is almost entirely absent.

In many parts of the world, cartoons may be dismissed as kids’ stuff, but in Japan, manga and anime are hugely popular across society. Stores in every town include racks of manga. Multiple broadcast and streaming channels feature anime series of all genres and styles. Ride Tokyo’s subway and you are likely to see many fellow travellers, young and old alike, reading manga or glued to anime on their phones. Some content is aimed solely at children or teens, but much also addresses adult concerns: war, social issues, sex and spirituality.

Japanese pop culture spread internationally during the 1970s and ’80s, as TV networks across the world began to screen anime dubbed into local languages. By the time one of the most successful series, Pokémon, premiered in 1997, anime was already in demand across the US, Europe and farther afield.

That popularity fuelled the imaginations of a global generation. One example is Captain Tsubasa, which centers on the exploits of soccer prodigy Tsubasa Oozora and his friends. It first appeared in 1981, serialized in a manga magazine and then broadcast on Japanese television. It is still in demand, with a new TV series premiering in late 2023.

Some 90 million copies of the manga are in circulation, across more than 100 editions, alongside dozens of TV shows, movies and video games. World-renowned former Spanish striker Fernando Torres, who played for several of Europe’s leading soccer clubs between 2001 and 2018, credited his childhood enthusiasm for the sport to watching Oliver y Benji, the Spanish-language dub of Captain Tsubasa.

In the Arabic-speaking world, Captain Tsubasa became Captain Majid.

“As a kid, I played video games and watched anime like Captain Majid and [giant space robot] Grendizer,” says Khalid Alshaye, 30, a business-development manager born and raised in Riyadh. “Everything was dubbed into Arabic, and I had no idea it was Japanese. I just loved it.”

Syrian writer Obada Kassoumah, 33, has spoken about how the streets in his neighborhood of Damascus used to empty when Captain Majid came on TV, as he and his school friends tuned in for the latest episode. Then, inevitably, they would head out to reproduce Majid’s soccer tricks.

“Once I tried to copy Majid so hard, I knocked myself out. I was imitating his [acrobatic overhead] kick and hit my head on the ground,” Kassoumah told Japanese news site Nippon.com.

After training for two years with a pro soccer club in Syria, Kassoumah won a scholarship to study in Tokyo. In 2017, he published the first translation of the Captain Tsubasa manga series into Arabic, evoking the vivid linguistic style of the original and restoring storylines that had been rewritten for broadcast to Arab audiences 20 years before.

The ubiquity of TV anime feeds a growing appetite for the art form. Anime has become “wildly popular in Saudi Arabia and the [Middle East],” writes Washington-based analyst Daniel Sharp, with Saudi Arabia hosting “the largest anime fan base in the region.”

That popularity has shaped policy. In 2017, the kingdom’s nonprofit Misk Foundation created animation studio Manga Productions to help kickstart a homegrown industry of manga, anime and video games. Manga Productions opened offices in both Riyadh and Tokyo and began hiring. Although there had already been some experimental short films made as Japan-Saudi co-productions, the 2017 agreement between Toei and Manga opened the door for a full-length animated feature. As part of the agreement, some 300 Saudi creatives moved to Tokyo to work with Toei.

Script development originated in Riyadh, under the title The Journey. The story was based on the legend of the Year of the Elephant, in which Abraha, a 6th-century ruler of the kingdom of Axum—modern-day Ethiopia and Yemen—led a vast army attacking Makkah, only to be repulsed by divine intervention. The tale is well-known from the Qur’an but is referenced there in only five short verses.

Creative content director Sara Oulddaddah, 32, outlines how The Journey’s script teams adhered to their source but also gave themselves the freedom to introduce material to help bring the story to life. They created a new protagonist, named Aws, and filled in his backstory. “We imagined, ‘What if this character had fought Abraha’s invasion and witnessed the incredible outcome of this uneven battle?’” says Oulddaddah.

“We never felt there was a power imbalance. Both sides were really eager to understand each other.”

—Sara Oulddaddah

With a story outline in place, responsibility moved to screenwriter Atsuhiro Tomioka. In 2018, Toei Animation also brought in director Kobun Shizuno—famed for his Godzilla anime trilogy—to helm the project. “Early on I went to Riyadh to meet the Saudi creative team,” says Shizuno, 50. “Their style was different, and I wanted to learn from them. From the start, I knew that we would be able to create something unique.” That exchange went both ways, as Saudi artists and animators also moved to Tokyo to work alongside their Japanese counterparts.

Aldhafeeri speaks of being “fascinated with how beautiful Japanese culture was” as a child. Having mastered the Japanese language in Saudi Arabia, he studied graphic design and illustration at Japan’s prestigious HAL Osaka technology college before being brought on for The Journey, initially as a cultural adviser.

“It was a challenge,” he grins. “I was working directly with the Japanese teams, and there was a lot of misunderstanding to start with.”

Oulddaddah clarifies that the misunderstandings were cultural. “For example, when we would discuss a sad scene, the Japanese team would think of rain—but for us as Saudis, when we see rain, we are happy. It’s very subtle, and it was fascinating to realize how what we think of as common sense is affected by cultural perception,” she says.

Body language was another complication. “If someone is angry, in Arabic we use a lot of hand gestures, whereas in Japanese they prefer expressions or body movement,” she says. For a scene with strangers meeting, Japanese artists would draw a character inclining their head, while Saudi artists would have them touching their hand to their chest. All these issues needed working through.

One of the contrasts proved especially positive, Oulddaddah notes. The age difference between the Saudi creatives, mostly younger than 35, and the Japanese team, mostly in their 40s and older, “really enriched the creative process. We never felt there was a power imbalance. Both sides were really eager to understand each other.”

“Directors are becoming more aware of Arab cultural influences, writing Arab characters and even hiring Arab voice actors in original Japanese productions.”

—Khalid Alshaye

Toei’s animators visited Saudi Arabia, traveling into the desert and experiencing the culture firsthand in order to inform their work. Voice actors added dialogue in Japanese and Arabic (an English-language dub followed), and music director Kaoru Wada composed a sweeping orchestral score.

The result, almost entirely hand-drawn, looks Japanese, feels Japanese and—in its original version—sounds Japanese, but is nonetheless a Qur’anic story that is steeped in Arab tradition. Visually spectacular and conceptually groundbreaking in its cultural blend, it “offered Saudi audiences a glimpse of stories told from their perspective using a popular foreign medium,” Sharp wrote.

Although The Journey was ready by early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic delayed its release. It eventually opened in Japan and Saudi Arabia in June 2021 in Japanese and Arabic versions, subtitled in English. An English dub screened in the US in 2022, and a German-language dub also followed, with the movie available worldwide on anime streaming service Crunchyroll.

Anime critic Ryota Fujitsu called the film “richly thought-provoking,” while Alex Saveliev wrote: “The amalgamation of Arab and Japanese sensibilities works to this unique film’s advantage.” A Japanese anime blogger who goes by the pseudonym Marion Eigazuke noted how The Journey focuses on “people who change the world through their powerful faith. This isn’t easy in Japan, where people have a loose connection to religion. It’s a beautiful achievement.”

One of the film’s most distinctive elements is its confidence in cutting away from the action at crucial points. Nested within the main narrative arc are three mini stories, designed to shed light on the sources of Aws’ determination to prevail against the odds. These sequences, told in flashback, draw on the Qur’anic tales of Noah, Moses and the mysterious lost city known as Iram of the Pillars to evoke hope in adversity. Each sequence has a unique look, decorative and stylized, in contrast with the fluid action of the main story. They are, in the words of reviewer Rebecca Silverman, “striking and…quite beautiful,” and reflect director Shizuno’s skill in adopting the story-within-a-story technique familiar from traditional Arabic folktales.

Oulddaddah, part of a creative community at Manga Productions that is 70 percent women, reflects positively on the production. “We recognize that Japan has exceptional creative power in this industry. Our aim with this collaboration was to transfer that knowledge to our team, to raise our own production capability.”

Internships and training programs run by Manga Productions continue to foster creative exchange between the two countries, while Saudi enthusiasm for Japanese pop culture shows no sign of waning. Jeddah and Riyadh host regular screenings and live performances, alongside the annual Saudi Anime Expo. In 2022 and 2023, Manga Productions announced new partnerships to develop two of Japan’s best-known anime franchises for global audiences: Grendizer—the space robot introduced in 1975, still with dedicated followings in Europe and the Middle East—and Captain Tsubasa.

“There are so many ways now to approach the market, and these stories carry such strong moral lessons,” says Manga Productions development executive Alshaye. He speaks of a tide of Japanese creators eager to develop content for Arab audiences, and notes that that is starting to have an impact. “Directors are becoming more aware of Arab cultural influences, writing Arab characters and even hiring Arab voice actors in original Japanese productions.”

As The Journey producer Shinji Shimizu remarks with a twinkle: “The journey has just begun.”

The writer thanks Tokyo-based journalist Makiko Segawa for her help in research and interpretation.

You may also be interested in...

Ithra Explores Hijrah in Islam and Prophet Muhammad

History

Arts

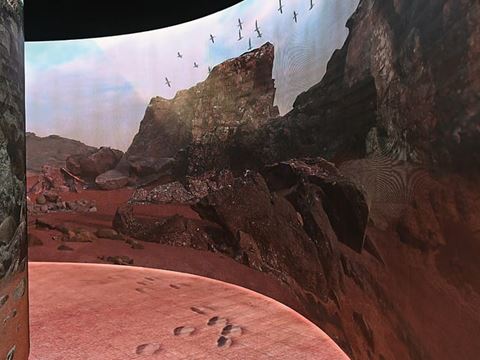

Avoiding main roads due to threats to his life, in 622 CE the Prophet Muhammad and his followers escaped north from Makkah to Madinah by riding through the rugged western Arabian Peninsula along path whose precise contours have been traced only recently. Known as the Hijrah, or migration, their eight-day journey became the beginning of the Islamic calendar, and this spring, the exhibition "Hijrah: In the Footsteps of the Prophet," at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, explored the journey itself and its memories-as-story to expand understandings of what the Hijrah has meant both for Muslims and the rest of a the world. "This is a story that addresses universal human themes," says co-curator Idries Trevathan.

Making Lawrence of Arabia

History

Arts

In 1919 American journalist and filmmaker Lowell Thomas glamorized British Army officer Thomas Edward Lawrence first in war propaganda and then in commercial cinema. His show traveled the world and gave birth to one of the most popular modern legends of Western involvement in the Middle East.

Sami Katafi and The Legacy of 'Mi Amigo Angel'

Arts

By tackling often overlooked societal issues, Palestinian-born Sami Kafati’s body of work has shaped Honduran cinema even years after his passing.