How Azza Fahmy's Jewelry Blends Egyptian History and Art

Azza Fahmy has become a legend in the world of artisanal jewelry from the Middle East. Her designs, now some of the most sought after in the Arab world and internationally, have long championed the history and culture of Egypt and the greater region with contemporary style, forms and vision—often with references to Pharaonic symbolism, Mamluk architecture, Egyptian modernism and vernacular cultures.

8 min

Written by Rebecca Anne Proctor Photographs Courtesy of Azza Fahmy Jewellery

Working side by side in four rows of vintage wooden craft stations, some two dozen craftsmen are making, by hand at every step, some of the most elegant and artistically influential jewelry in the Middle East. The workshop belongs to jewelry designer Azza Fahmy, and it lies in the basement of a practical building that sets itself apart from the surrounding warehouses and showrooms with nods toward the historic architecture an hour’s drive to the east in medieval Cairo.

Born in 1945 in Sohag in Upper Egypt, Fahmy has become a legend in the world of artisanal jewelry from the Middle East. Her designs, now some of the most sought after in the Arab world and internationally, have long championed the history and culture of Egypt and the greater region with contemporary style, forms and vision. This includes references to the poetry of Lebanese poet and writer Kahlil Gibran, pharaonic symbolism, Mamluk architecture, Egyptian modernism and vernacular cultures.

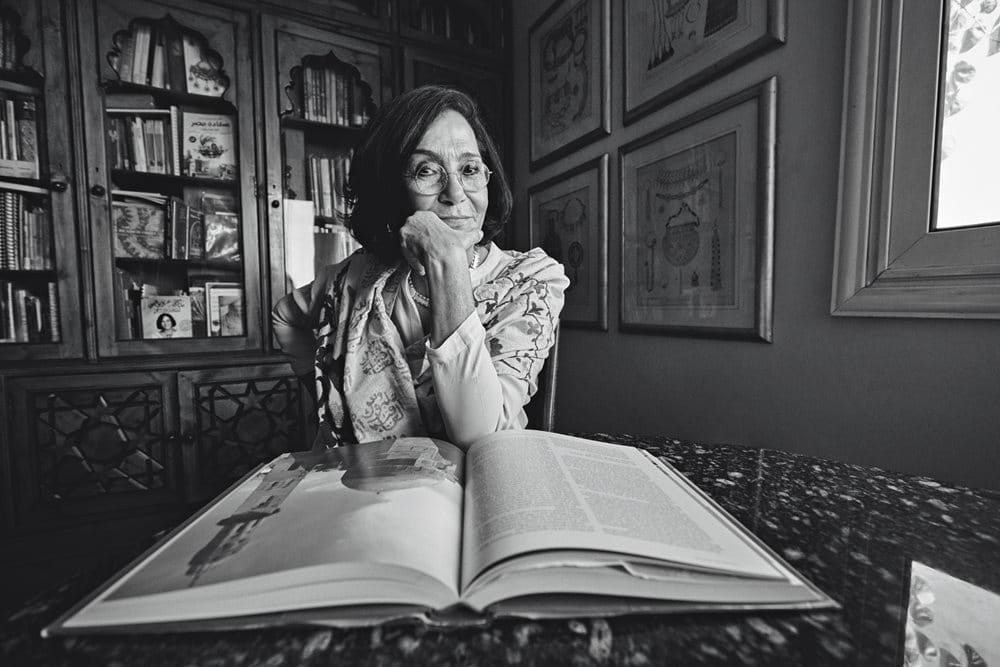

“Jewelry is intellectual, for through it we can share our Arab history, culture and identity with the world,” says Fahmy in her office adjacent to the downstairs workshop. She sits nonchalantly at her table made from an old Egyptian heritage door and covered in glass, as she takes a sip of her coffee. “I do what I do with love,” she says with a smile. “A love for my country, a love for jewelry and a desire to share this with humanity.”

She also does it with passion to research the vast sweep of histories in her homeland and to then interpret them in jewelry. Fahmy graduated in 1965 from Egypt’s Helwan University with a bachelor’s degree in interior design, and in 1969 she discovered a book about medieval European jewelry design. Transfixed and enchanted, she says it was then she became aware of her true calling. While continuing her day job illustrating books for the government, Fahmy broke into a traditionally male world to train under the master goldsmiths of Khan el-Khalili, Cairo’s historic bazaar.

“I tied my hair back, put on my overalls and spent my days in a workshop full of men learning the tricks of jewelry making,” she recalls on her website. “I never thought of what I did as unusual or difficult. I just did it with love, and it happened,” she says from her office next to her workshop. “I never thought, ‘I’m a woman, I can’t do this, and I am in an environment only for men.’ I saw my early training as an experience, a flow and a way to learn. I continued to meet many people and craftsmen who inspired me. I did what I did because of my love for jewelry.” While the craftsmen at Khan el-Khalili perfected their familiar designs laden with pharaonic motifs, Fahmy watched, studied and took her own novel direction into a fusion of past and present within the forms and styles of the contemporary. A British Council grant gave her the chance to study at the London Polytechnic’s Sir John Cass College, where she also learned techniques of manufacturing.

She came back to Egypt soon afterward. “I can’t leave Egypt,” she says. “I am like a fish—if you take me away from the country, I won’t be inspired, I won’t be able to create what I do here.” In Cairo she set up her first eponymous atelier with two employees, and she set out to design pieces imbued with Egyptian history and culture with a focus on often overlooked aspects. One of her first collections, Houses of the Nile, created during the 1980s, was inspired by the traditional architecture, unique geometric decorative pattens and Nile-side palm trees of Nubia, the historical land that straddles today’s boundary between Egypt and Sudan. Crafted with a realism rare in fine jewelry—so much as to make the pieces akin to dioramas—she was yet able to shape them with the abstract curves and forms of contemporary sculpture. The result was an act of cultural preservation: Both the wearer and the viewer feel that these houses, many of which no longer exist, are still present, living designs.

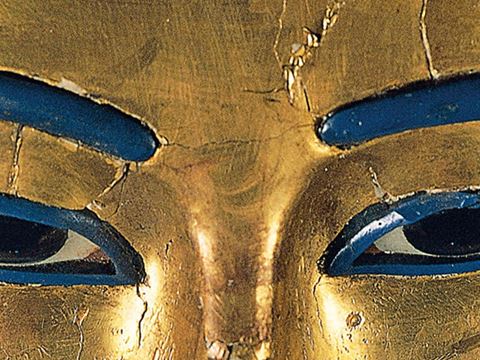

In 1990s she furthered what was becoming her signature style, this time through contrasting combinations of gold and silver, and this led to her trademark Pharaonic Collection. It was work that, she explains, took years of research as well as the advice of an Egyptologist, all to produce a jewelry line that reflected both a modern spirit and a fidelity to historical facts.

“Jewelry has always been an important part of Egyptian culture because it was a way to prepare for the next life,” she explains. Through this emphasis on marrying the past and the present through elegant craftsmanship and attention to detail that ranges from elemental to extravagant, Fahmy has pioneered the popularity of intellectual jewelry—jewelry that is an object of esthetic beauty and also serves as a document of heritage.

More recently several of Fahmy’s collections have incorporated quotes from poems and proverbs in Arabic that celebrate the heritages of Arab-world scholars, poets and writers. This has proven inspiring to other designers in the region, such as Dubai-based Nadine Kanso, whose Bil Arabi line similarly celebrates not only Arabic literature but also the beauty of its calligraphic forms.

“Azza Fahmy is inspiring younger generations of Egyptians to become artists and designers and work with their hands like a traditional craftsperson,” says Egyptian architect Omniya Abdel Barr, who adds that until Fahmy became well known in Cairo, Abdel Barr’s own grandmother would never have worn a ring with a design referencing ancient Egypt. “When she began 50 years ago, this was unheard of. To engage with such crafts was done by different social classes. Azza elevated the rank of craftsmen, made us feel pride in traditional crafts, and in Egypt’s heritage,” says Abdel Barr.

Fahmy attributes much of her love for discovery and celebration of her homeland to her father. Even at age seven or eight, and living in Upper Egypt, she recalls her father taking her to visit monuments. And at home, she adds, “we had a huge library filled with books where I could study, and then he would take me to different parts of Egypt where I learned about the Pharaohs, the Copts and other periods and cultures,” she recalls. “It made me curious to learn more, and this was thanks to my father.”

Fahmy has always been a diligent student. She is also the author of books including Enchanted Jewelry of Egypt: The Traditional Art and Craft (2007), The Traditional Jewelry of Egypt (2015) and My Life in Jewelry: A Memoir, which she wrote in Arabic together with Sarah Enany, and which is forthcoming in English this fall.

“Azza Fahmy is inspiring younger generations of Egyptians to become artists and designers and work with their hands like a traditional craftsperson.”

—Omniya Abdel Barr, Egyptian architect

“Azza Fahmy is always eager to learn, and that is something that I love about her,” adds Abdel Barr. “She’s taught me that it is never too late to learn and to dedicate oneself to what they love. That is why her business is so successful. She cares about quality and the message she’s delivering. She cares about being authentic and genuine. Azza always says, ‘We design, we don’t copy.’ In this way she is constantly trying to promote Egyptian art and culture whether it is through her jewelry with their sculptured architectural design or through her written words.”

It’s this personal and genuine way of expressing her love for Egyptian culture and heritage that has gained Fahmy such a dedicated fan base among Egyptian and international celebrities and designers. Friends of her brand include Egyptian model and actress Elisa Sednaoui, Jordanian actress Saba Mubarak, Tunisian-Egyptian actress Hend Sabry, Egyptian actress and singer Yousra and Egyptian soprano Fatma Said. Over the last two decades she has found a growing international market largely through fashion as well as educational and cultural partnerships. These include collaborations with Preen, Matthew Williamson and Julien Macdonald at London Fashion Week in 2006 and with Justin Thornton and Thea Bregazzi at New York Fashion Week in February 2010. In early 2012 Fahmy worked with the British Museum to create a custom collection for its landmark exhibition Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam, inspired by the pilgrimage and its rituals. Most recently, in 2022, she collaborated with Balmain’s Creative Director Olivier Rousteing on a one-of-a-kind bustier inspired by Egyptian symbolism.

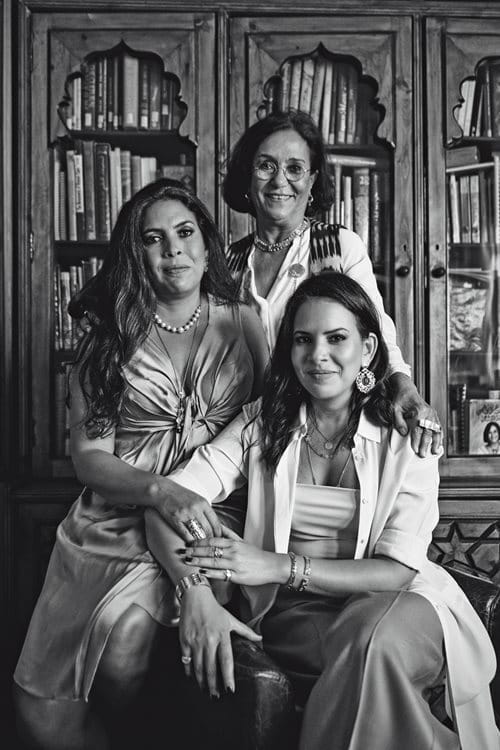

Since 1988, when she opened her first gallery, El Ein, with her sister Randa in Cairo’s Mohandessin neighborhood, Fahmy has launched numerous boutiques, concession stores and flagships in Egypt, and now internationally in London, Dubai, Amman and AlUla, Saudi Arabia. While the business continues to grow and a launch into the US market is in the works, her nine-year-old Azza Fahmy Foundation encourages young designers in Egypt and across the Middle East and North Africa.

“It’s crucial to give back and teach the next generation of designers,” she says, “particularly those with few opportunities.” The foundation was created to offer job opportunities, vocational training and start-up support in craft-based industries to marginalized Egyptian youth. Its focus on crafts both Egyptian and from cultures around the world ensures the preservation of traditional craftsmanship—a practice continually under threat.

Fahmy also in 2013 established The Design Studio by Azza Fahmy, in partnership with Florence, Italy’s Alchimia Contemporary Jewelry School. This studio serves primarily as a jewelry-making vocational school, and it was the first of its kind in Egypt and the Arab world. With courses that blend traditional techniques with alternative creativity, it is shining a spotlight on Egypt as a growing hub in the Middle East for jewelry design.

It would be easy to regard these schools along with her many jewelry creations and dedication to a handmade process as her legacy. But that is not how she sees it. “Jewelry as an expression of love is a notion that has colored all my work,” she says, smiling again. “I don’t want to leave a legacy. I just want to leave love.”

You may also be interested in...

Pretty and Protective: Egyptian Kohl Eyeliner

History

Arts

Science & Nature

The black eyeliner known widely today as kohl was used much by both men and women in Egypt from around 2000 BCE—and not just for beauty or to invoke the the god Horus. It turns out kohl was also good for the health of the eyes, and the cosmetic’s manufacture relied on the world’s first known example of “wet chemistry”—the use of water to induce chemical reactions.

The Meaning of Henna and Its Rise in the West

Arts

The smell of eucalyptus and lavender oil mingles with the earthy aroma of henna paste lingering in the room. Jaya Robbins’s hands, already stained with henna on the tips, carefully pour a freshly made paste into a plastic pastry bag atop a large cup covered with a single pantyhose sock.

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.