Karabakh Horse Rides Again: A Comeback for a Azerbaijan Treasure

Strength, speed and a lustrous coat made the Karabakh horse a symbol of status, power and beauty in its native Azerbaijan, and beyond. Wars over the past century nearly eliminated them, but now breeders are steadily restoring their numbers.

Written by Tristan Rutherford Photographed by Rebecca Marshall

As director of the Agjabedi Horse Center in the highlands of western Azerbaijan, Elman Qadirov starts each day at his desk under the gaze of an artist’s depiction of a spellbindingly beautiful horse with a radiant, golden coat the color of burnt butter. The horse is a Karabakh. Outside his window Qadirov can see some of the approximately 300 purebred Karabakhs currently being reared in the center that includes a laboratory, an indoor riding area and even a horse spa.

The high-tech center opened in 2018 for one reason: Just a quarter century ago, the Karabakh breed, native to the central Caucasus and emblematic of its equine heritage, was on the brink of dying out.

The story of the Karabakh started on the other side of the Caspian, on the grasslands of the Turkmenistan steppe. Here the Turkoman horse—extinct now for more than 1,000 years—had adapted to the steppe’s rocky, barren terrain with tough hooves and an extended back for long-distance riding. The Turkoman gave rise to Turkmenistan’s famously sturdy, nimble Akhal-Teke breed that similarly could cover great distances. One of the oldest of the world’s 200-plus horse breeds, and with a history stretching back at least 1,000 years, the Akhal-Teke is a prominent parent breed of the Karabakh.

The Karabakh’s home in the Caucasus meant the breed carried these steppe characteristics to a land slashed by snowcapped mountains and pockmarked with deep valleys and lakes. Its tight, muscular frame and slender limbs gifted Karabakhs superior abilities both to climb mountains and gallop through flatlands at pace. The horses adapted also with uncommonly large nostrils that can dilate in warm weather and constrict in the mountain air more than other breeds. According to Qadirov, this evolution allows the Karabakh to climb up to where even a truck might seize up in the thin air and cold. So exceptional were the best Karabakhs that, up to three or four centuries ago, they were one of the top gifts bestowed by regional khans.

The breed was certainly in its current physical shape and form 250 years ago, in the late 18th century, when the Palace of Khans was constructed in the city of Shaki, which lies in the mountains 150 kilometers north of Agjabedi. This former royal residence, today inscribed as a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), was built without using a single nail. It took two years to build, but another six to decorate: Every wall is painted with multicolored scenes and patterned frescoes. One salon displays a hunting scene with 140 horses galloping around the entire room, and among them, the Karabakhs are recognizable by their glowing coats in shades from light cinnamon to burnt gold.

“Karabakh horses were a symbol of power and beauty,” says Zamina Rasulova, a palace guide since 2004. “The unseated horses in the palace frescoes depict Karabakhs that were given as gifts from Azerbaijani khans, usually following a peace agreement,” she continues. The breed was so integral to regional culture that if a Karabakh’s owner died, the horse was declared “a widow.” If authorities wished to punish somebody, they would cut the hair of their Karabakh.

Rasulova, whose book, The Notes of a Palace Guide, was published last year, points also to Azerbaijani proverbs, many of which, she says, refer to horses. These include sayings such as, “A horse is the wings of a man,” “A good horse adds beauty to any hero,” and “A nail will protect a horseshoe, a horse will protect a hero, a hero will protect a people.”

“Karabakh horses were a symbol of power and beauty.”

—Zamina Rasulova

The Karabakh horse also lends its name and silhouette to Azerbaijan’s current football league champions Qarabağ Futbol Klubu. (The country’s premier women’s league champion is currently the team from Shaki.)

Trade along the Silk Road made Shaki wealthy. Beginning in the first century CE, horses and carts loaded with metalwork, carpets and spices were carried to and from mainly China and what are now Uzbekistan and Pakistan. Caravans tied up inside the 300-room caravanserai that sits a few minutes’ walk from the Palace of Khans. Until the 1970s, Shaki residents still reared silkworms inside their handsome homes, which were for the most part built from river stones washed down from the mountains.

The Silk Road required horses that could trot tirelessly across any topography. “We have needed horses since ancient times,” confirms Mammad Ahmadov, director of the Palace of Khans. Craftsmen came by horse with goods to sell, and for those who could afford them, Ahmadov adds, Karabakh horses were preferred to venture into the forest and mountains to help bring wood for heating. In addition to its other qualities, the Karabakh’s svelte coat is surprisingly warm.

Every year in Shaki, Ahmadov continues, “we host çövken games where we use Karabakhs.” In 2013 UNESCO inscribed çövken (chov-KEHN), a hurly-burly ancestor of polo, onto its list of intangible heritage. But unlike polo, in which players wear riding helmets, çövken players wear traditional lambswool Astrakhan hats. From the saddle they wield wooden mallets big enough to thwack a ball about the size of a football. It’s a high-velocity, 45-minute contest that would, Ahmadov maintains, tire most other breeds in minutes.

Paintings depict the game being played in the Caucasus as far back as the ninth century CE. The Book of Dede Korkut, a 14th-century Turkic-language epic that gathered tales from Central Asia, also described a stick-and-ball horseback game with the words, “Your lovely back can take one to its goal. I shall not call you horse, but brother.”

Qadirov, at the horse center, once also served as an umpire in the Shaki çövken tournaments, and he is author of today’s official rules of the game. The drive from Shaki to Agjabedi winds through the kind of high hills in which Karabakh horses thrive. Forests of mulberry trees, the leaves of which form the sole nutrition for silkworms, line the route. Each successive village specializes in a different fruit, from grapes and plums to apples and apricots. The road follows a river the color of Azerbaijani tea, and its waters host carp that is served in roadside restaurants.

Qadirov explains that the game plays to the Karabakh’s strengths to turn rapidly and block an opponent as their small head and slender legs grant them not only unrivaled endurance but also speed. The record average across a 1-kilometer course is 52 kilometers per hour, which compares to most other breeds’ top gallops that tick in between 40 to 48.

It was in the 19th century that the breed began to attract interest from outside the Caucasus. In 1823 a British company purchased 60 purebred mares from the last Karabakh owned by a khan. In 1867 a stallion, aptly named Khan, won a silver medal at the Universal Exposition in Paris.

Yet increasing unrest in the Caucasus began to curtail the stock. The rising power of Russia to the north demanded large, pack horses to carry goods across its vast distances, such as the Don, of which the Karabakh is a parent. But a century ago the Karabakh was decimated during battles between the Soviet and anti-communist forces. It was diminished further in 1993 when another conflict broke out among newly independent, formerly Soviet states of Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Qadirov explains how the surviving Karabakhs narrowly escaped. “I was born and raised in Aghdam, a flat area at the foot of the mountains, where the Karabakh horses are from,” he explains, where his uncle was “an important man” at the Aghdam horse farm. Together with five colleagues, the team drove nearly 400 horses across open fields to escape shelling. The journey to a safe space in Agjabedi took several days. Not one horse was lost in the escape, although it required the men to leave most of their personal possessions behind. Yet tragically wartime food shortages ravaged the herd, and by 1997 as few as 50 purebred Karabakh horses remained.

Today the breed appears to have found a haven at the Agjabedi Horse Center. Written on a plaque in front of each stable is each horse’s name, parentage, age, gender and coat color. Many Karabakhs have a white, diamond-shaped mark on the forehead, as if they have been struck by lightning. When trainers walk past their comfy stables, the horses regularly lean out to give him or her a kiss. “I love them,” says Panah Allahverdiyev, an Agjabedi graduate who now trains other riders. “I wanted to be a trainer since childhood.”

This 1956 photo shows Zaman, the stallion gifted that year to the United Kingdom’s Queen Elizabeth II. The jockey is Ali Tagiyev, grandfather of trainer and Baku Golden Horse Therapeutic and Educational Center founder Sarxan Tagiyev, shown below carrying on his family tradition of breeding and training Karabakhs and educating people about them.

From the stables, jockeys Cafar Cafarzada and Kurkan Huseynov trot their horses Qalam and Siyazam to the adjoining racetrack. Both riders are proud to perform a walk, trot, canter and gallop to show off “our heritage, our blood,” says Cafarzada. The walking gait hits a 1-2-3-4 beat as the horse uses its slender legs independently. The trot pairs limbs diagonally to pick up speed. The canter is quicker still until the horses blister forward with three legs off the ground at once, propelled alternately by a single rear leg.

Then the horses gallop. For the briefest of moments in each pounding, four-beat gait, all their legs are suspended in the air after every limb has powered forward. The sight is mesmerizing in its force; in the saddle, the jockeys claim, the ride is undulating, wildly exciting and not at all smooth like an English trotter. Qalam and Siyazam thunder past in a cloud of dust before halting with whinnying cries, their golden coats shimmering in the sun like liquid gold.

Jockeys describe riding a Karabakh at full gallop as an undulating, wildly exciting ride.

Qadirov explains how when Azerbaijan was part of the former Soviet Union, the Soviet state safeguarded—and monetized—Karabakh DNA beginning in the 1920s, but collectivization meant horses were taken away, too, in great numbers. “They left only 87 pureblood horses in the yards of people in different villages,” he explains. In 1934, Soviet scientists gathered more Karabakh horses in Shaki to make the best breeding selection. “Each summer, some of the herd would climb toward the top of the Caucasus mountains,” and the offspring were sold across Europe and Russia.

Orucov Natig, a master jockey and trainer at the Agjabedi Horse Center, has worked with Karabakh horses since 1977. During the Soviet period about 50 Karabakh horses were sold abroad each year in exchange for much-needed US dollars, he says. In the 1990s overseas sales were halted, as the Karabakh herd dwindled.

Today there is a slow lift on the ban of Karabakh sales. After much breeding, about 30 horses are sold per year within Azerbaijan, Natig confirms. The starting price of a Karabakh horse begins from the equivalent of US$3,000—roughly equivalent to the average price of a privately sold horse in the US. However, a top horse can fetch much more: At one auction last year, the price of a horse named Sultan began around US$18,000.

Some of the horses are sold to private stables on the shores of the Caspian Sea in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. A new high-speed train, which shuttles across the nation of 10 million people, describes a rapidly modernizing country that remains a continental crossroads. Moving far faster than Silk Road riders ever dreamed, the scenery outside the train leaves behind the orchards and rural greenery as it gallops through rows of oil derricks that pounce up and down like giant ants and then sprints into Baku past skyscrapers and a glittering cultural center designed by the late architect Zaha Hadid.

Sarxan Tagiyev is the founder of an equestrian club next to the Baku State Hippodrome. Inside the stadium, Karabakh horses nibble grass alongside a circular racetrack as more horses rest in stables inside the complex.

Mirroring the Caucasus tradition of gifting horses, Soviet authorities in 1956 decided to use a Karabakh horse as a diplomatic present to England.

As Tagiyev pats his beloved Karabakhs, he recalls a remarkable relationship with the breed that goes back generations. His grandfather Ali and his great uncle Calal started to collect horses in Aghdam in 1946, just after the end of World War II. A decade later, the Soviet Union wanted to cultivate relations with other countries. Mirroring the Caucasus tradition of gifting horses, Soviet authorities decided to use a Karabakh horse as a diplomatic present to the United Kingdom. “They received advice that the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II loved horses,” explains Tagiyev. The horse the Soviets wanted to gift to her was a Karabakh named Zaman, born in the Aghdam horse center in 1953, the same year UK had crowned the young queen.

Here the Soviets hit a problem. “They struggled to find a chaperone to accompany Zaman to London because the chairman of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, didn’t like any of the jockeys they presented,” explains Tagiyev. The authorities discovered that Tagiyev’s grandfather had taught military leaders how to ride on parade and that he looked suitably handsome in a national costume. In 1956 Ali Tagiyev was groomed to ride for the queen and to be prepared to answer questions she might pose. “He became the first Azerbaijani jockey in Britain,” says his grandson with a smile.

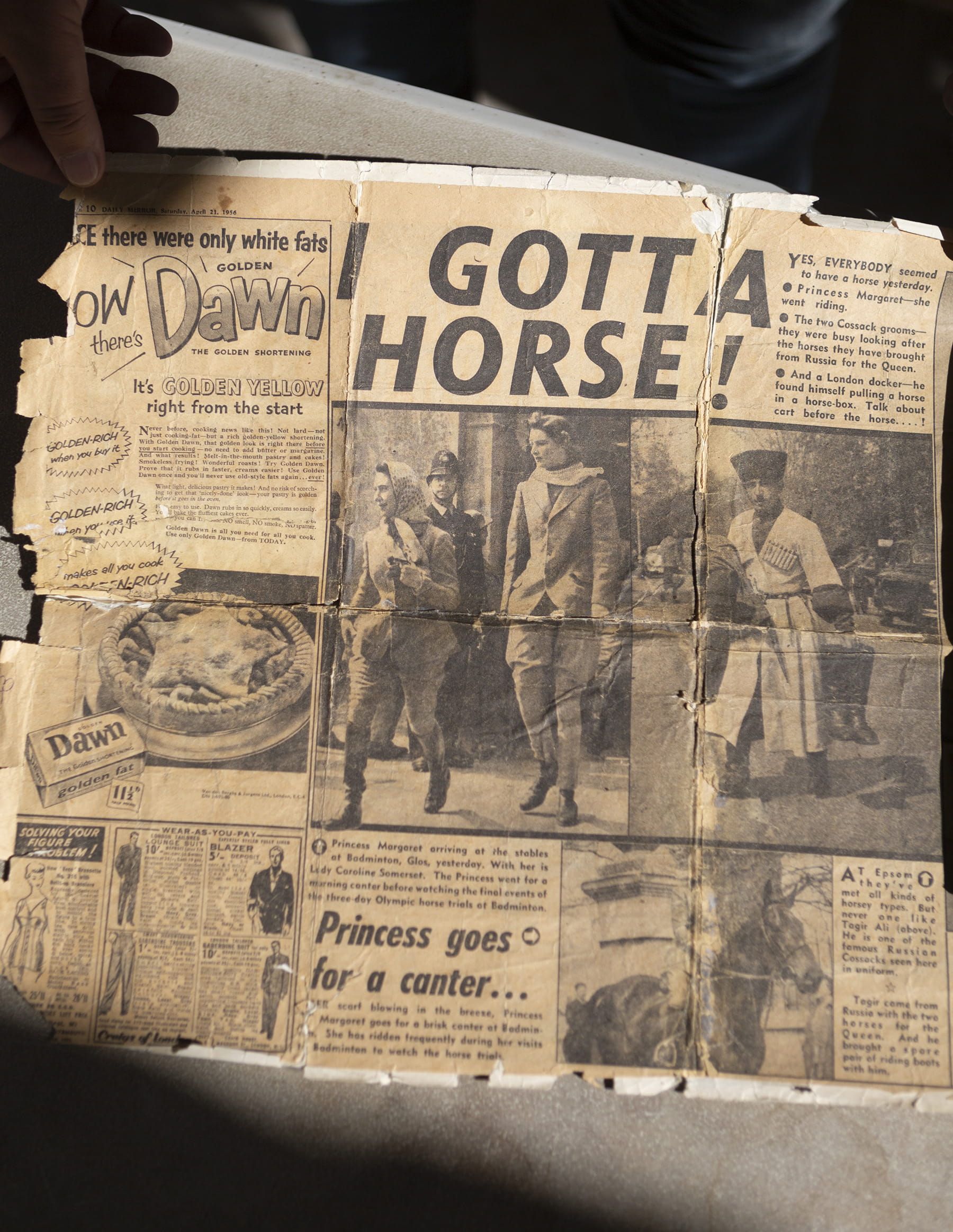

At Windsor Castle, Tagiyev continues, “the queen asked my grandfather to train her new Karabakh horse and stay in England for 10 days.” He unfurls a collection of yellowing UK newspapers that show the national rapture the golden-coated Zaman inspired. “I Gotta Horse!” headlined Britain’s Daily Mirror on April 21. “At Epsom [racecourse] they’ve met all kinds of horsey types. But never one like [Tagiyev],” who was pictured in his traditional costume, wearing leather riding boots and an Astrakhan hat. So notable was Zaman’s unique coat that it even sparked fashion trends, as women allegedly began choosing jackets and coloring their hair in golden hues.

As he pets one of his Karabakhs, Tagiyev describes the history. “My little brother Jamal went to Britain in 2012 with three more horses” to perform at the Royal Windsor Horse Show.

On the east side of the capital, the Karabakh’s resurgence gets confirmation also from the Royal Pegasus Stables, the workplace of Svetlana Kuznetsova. As registrar of the Equestrian Federation of Azerbaijan, Kuznetsova helps compile the Karabakh’s official stud book—the authoritative documentation of the entire breed.

“I first saw Karabakh horses in the hippodrome when I was about 9 years old,” says Kuznetsova as she overlooks the stable of a frisky. 18-month-old stallion named Ucan. “It’s important to create a stud book to keep the pedigree pure,” she continues. “Especially as we only have a small number of them.” The records go back to the Soviet era when every detail describing which stallion paired with which mare on which date was written into the ledgers by hand.

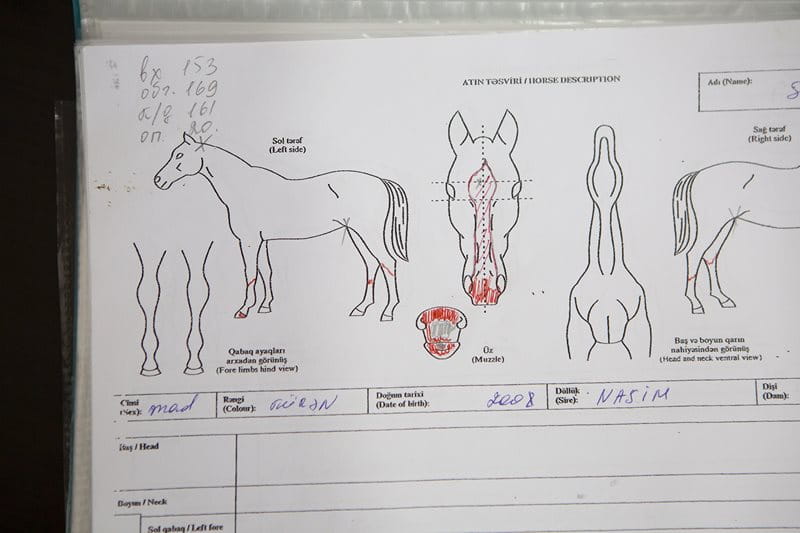

Today Kuznetsova’s task merges big data with pen and ink. “Breeders still need to draw a diagram of each horse,” says Kuznetsova. “Every equestrian passport still contains one.” Kuznetsova believes that only a horse with seven generations of proven parentage can be considered pedigree. To this end she hunts down parent horses all over the country to cross-reference records, count the foals and take DNA samples.

“We used to send blood to a laboratory for DNA analysis,” Kuznetsova explains. “Blood samples are very complicated, as sending them abroad requires loads of documents.” Now she sends horsehair samples to a DNA laboratory in Germany, “which is much easier.” The gene sequence of each horse is then saved onto a microchip that is inserted painlessly near the top of each horse’s neck as a record for the future.

Back at the Agjabedi Horse Center, Qadirov, too, has been involved in the Karabakh stud book. He helped compile an earlier printed edition of it, and he is strolling the stable complex during another busy day. The feral spirit of the Karabakh comes out as three young stallions are trotted toward a trailer, en route to a DNA test and as frisky as children. One of the trio rears up; its slender legs kick skyward. Then the horse accelerates across the manicured grounds until the soothing voice of its trainer cajoles it into the trailer, an unvanquished spirit, ready to break into a new era at a gallop.

About the Author

Rebecca Marshall

Rebecca Marshall is a British editorial photographer based in the south of France. A core member of German photo agency Laif and Global Assignment by Getty Images, she is commissioned regularly by the New York Times, Sunday Times Magazine, Stern and Der Spiegel

Tristan Rutherford

Tristan Rutherford is a 7-time award-winning journalist. His writing appears in The Sunday Times and the Atlantic.

You may also be interested in...

King of the River of Giants

Science & Nature

What do you do after you discover a dinosaur that swam, clawed and chomped its way to the top of the Cretaceous food chain? Paleontologist Nizar Ibrahim wants to display it where he found it—in Morocco.

A Quest to Restore the Marshes of Iraq

History

Science & Nature

Until the 1990s, the reed marshes of Iraq were Eurasia's most extensive wetlands, with a unique ecology that supported the Marsh Arabs' distinctive way of life. Then the marshes were drained and the people scattered. Azzam of Alwash, the emigré son of an Iraqi hydrologist, now works with international aid groups and Iraqi authorities to restore the desiccated marshlands. Reeds are sprouting, birds and fish are returning-and so are people. "A 7000-year-old culture doesn't die in a decade, he says.

Drone Seeding Aids Mangrove Carbon Sequestration

Science & Nature

Mangroves have been drawing increasing global attention for a quiet superpower: the ability to store up to five times more carbon than tropical forests. While coastal development, uncontrolled aquaculture, sea-level rise and warming temperatures have all contributed to the 35 percent decline in mangrove forests worldwide since the 1970s, government agencies, scientists and local communities are increasingly rallying to protect and replant mangroves. One group is taking restoration to notably new heights.