A Personal Exploration of the `ud: A Conversation With Rachel Beckles Willson

Entranced as much by its sound as by its centuries of history, in 2010 Rachel Beckles Willson started playing the `ud (oud), building enough skill to start performing on the instrument. She also became curious about its origins.

Growing up in London, Rachel Beckles Willson was surrounded by Western classical music. Her mother, a children’s book author, played piano at home, and when she wasn’t playing, BBC’s Radio 3 filled the air with Mozart, Beethoven and Bach.

“I don’t think there was any moment in my life when I didn’t think I’d be working with music,” Beckles Willson recalls now.

Beckles Willson’s own skillful playing won her a place at the Royal Academy of Music studying piano performance, and she later became a concert pianist. By the time Beckles Willson obtained her doctorate from London’s King’s College in 2003, she chose to focus on academia, hoping to balance performance and research. But she let go of performing, as it didn’t seem possible to do both.

That is until she discovered the `ud (oud), the pear-shaped lute descendant found in the Middle East and North Africa.

Entranced as much by its sound as by its centuries of history, in 2010 Beckles Willson started playing `ud, building enough skill to start performing on the instrument. She also became curious about its origins.

In 2016 she won a fellowship to explore how the instrument has been used around the world. That research resulted in her latest book, The Oud: An Illustrated History, an engaging chronicle featuring a wide array of photos, drawings and illustrations.

Today Beckles Willson is a professor of intercultural performing arts at Codarts University of the Arts, in Rotterdam, and Leiden University in the Netherlands. She performs whenever she gets the chance.

AramcoWorld caught up with Beckles Willson to discuss her book, and her personal and scholarly exploration of one of the world’s most iconic musical instruments.

Images from The Oud: An Illustrated History include a postcard sent from Constantinople in 1929 highlighting two female ‘ud performers.

How did you first meet the `ud?

I was writing a book in 2006 about European musical missions in Palestine and met `ud player Nizar Rohana. He showed me his collection of historic `uds. Each one was different. Each had a unique sound and story. I was completely captivated. Whenever I returned to the region working on that book (published in 2013), I would meet with him.

A few years later, I was living in Berlin and had a circle of Syrian friends. Often, when we got together, someone would have an `ud, and everyone would start singing. When I moved back to London in 2010, I decided that I needed to have an `ud in my new home. So I bought one and started trying to play it.

What place does the `ud hold in Arab society?

I think the `ud has a particular symbolism for the Arab world. It’s an instrument that people in the Arab world are obsessed with. Many people absolutely love it. It’s very much connected, I believe, to identity and probably to male identity in the Arab world. It’s a treasured thing, it isn’t just an instrument.

How do you explain the origins of this symbolism?

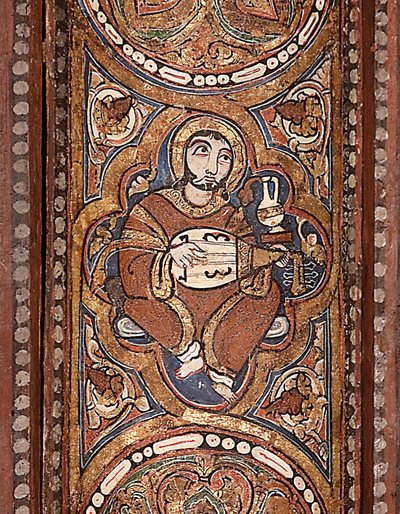

It comes, in part, from its history. The `ud was played at the time of the great Arab civilizations, the caliphate when there were thousands of women, great choirs of women playing the `ud. It was a time of great plenty, of joy, at least in the courts, where we have the sources, and the `ud was there. I suspect it still carries a sense of this past greatness.

Then there’s the instrument’s physical beauty. Each `ud has the opportunity for wonderful decoration, even calligraphy in the rosette.

Was it challenging to learn to play it yourself?

It’s a very awkward thing for a woman to hold. For a small female like me, the standard Arab `ud is very large, making it extremely uncomfortable and difficult. I couldn’t get my arm around it. Then it’s very hard to hit the right string. You can’t see what you’re doing when the `ud is in the correct position, which is facing away from you. The `ud slips in your lap until you get the knack. So, there are all sorts of difficulties, in combination with the culture, that expects you to just “get on with” this marvelous instrument.

Your book is not so much an academic work as it is a personal guided tour through a rich woven tapestry of ideas, stories and themes. Why did you write it this way?

We know history isn’t a straight line. As the `ud moved through time, there were at least three parallel developments in different countries, which may or may not be connected. So how do you tell three or more stories happening at the same time? It becomes impossible. I approached it more topically with themes while following a broad chronology. The book is intended to engage people who pick it up, look at the pictures and read a chapter or two. They should get something out of it, even if they read just one chapter.

What do you hope readers will learn from your book?

A richer understanding of the instrument and the cultures around it, as well as its history. I hope readers will discover connections between spaces that are sometimes separated.

I also feel passionate about telling the stories of women `ud players, about recognizing that the `ud has a very deep history with women. Currently, it’s associated with men, but that is very recent. I was able to source and include several old photographs of women playing the `ud in the book.

As an `ud player yourself, you prefer to play older instruments. Why is that?

I think every `ud player has their preference. I’m very attached to two `uds, both extremely imperfect, both made by Armenians. One is a tiny `ud made by Ali Galip in 1920. The other one is a larger one made by Beirut-based craftsman Leon Istanbuli.

There’s something different in the way these two instruments sound, but it’s not obvious. Frequently there’s something less direct, a little more complex. The sound might not be technically as good as a modern instrument, but it just pulls me.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

You may also be interested in...

Mappila Rhythms, Monsoon Connections

Arts

It was mainly the pepper in Kerala, at the southwest tip of India, that lured early traders to ride seasonal monsoon winds across the Arabian Sea. With the mariners came music that mixed with Keralan sounds to become the complex, percussion-driven traditions of today’s Mappila culture.

Tracing American Jazz's Roots to the Nile

Arts

The Nile river has been used as motif, a metaphor or both in popular culture, most prolifically in music in the United States for more than 125 years. The most notable uses of the Nile arose during the jazz period, which peaked in the second half of the 20th century and continues to this day.

Moroccan Musician's Mission: Revive Overlooked Folk Traditions

Arts

For more than 10 years, Moroccan native and New York resident Hatim Belyamani has focused his non-profit Remix⟷Culture on offering digital sample and remix tools that give exposure and preserve access for traditional acoustic music around the world.