Finding Structure: A Conversation with Author Eric Broug

As a boy living in Jakarta, where his Dutch father worked as a civil engineer in the early 1970s, Eric Broug grew fascinated with Islamic culture. By the 1990s, after having begun studies in Middle Eastern politics at the University of Amsterdam, Broug turned his interest to Islamic geometric design and joined the master’s program at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies in Islamic art and archeology.

As a boy living in Jakarta, where his Dutch father worked as a civil engineer in the early 1970s, Eric Broug grew fascinated with Islamic culture. By the 1990s, after having begun studies in Middle Eastern politics at the University of Amsterdam, Broug turned his interest to Islamic geometric design and joined the master’s program at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies in Islamic art and archeology.

After finishing the program in 2002, Broug began recording instructional videos in Islamic design principles and giving lectures and workshops around the world. Over the course of his career, he has also published three books on the art of patterning circles, squares and other geometric shapes in arabesques designed to represent the infinity of God.

The success of these books (translated into at least half a dozen languages) gave way to Broug’s numerous workshops and lectures around the world, as well as several video tutorials teaching the principles of Islamic design.

Now, after 25 years focused on design, Broug has turned his attention back to Islamic architecture, resulting in his latest book, Islamic Architecture: A World History.

Broug recently spoke with AramcoWorld about his career evolution and the origins of his new book.

What led to your interest in Islamic culture and design?

I’ve always been focused on the beauty of Islamic architecture and on the ornate, intricate patterns and designs that decorate these structures. After four years studying Middle Eastern politics in Amsterdam as an undergraduate in the 1980s, I wanted to find something that would allow me to give something—a big challenge, an impossible dream.

Then a book came onto my path—Arabic Geometrical Pattern and Design, by [J.] Bourgoin. I found it fascinating because it’s art, history and science, and Islamic geometric design was under-researched at the time. I thought, if I’m going to choose something this obscure, then I must do it 100 percent and never give up.

Your search for images for this book led you to review more than half a million photos. How did you decide what buildings to include?

I knew that certain buildings would have to be in there, like the Alhambra [Spain] and the Topkapi Palace [Turkey]. But the interesting thing was to see whether I could find less well-known Islamic architecture examples like the mosque in Kouto in the Ivory Coast, or the Mubarak Mosque in Prek Pnov, Cambodia, structures that don’t receive as much notice for their architecture because of where they’re located. It took a lot of time to find such buildings. I couldn’t do every country, but I did want it to be globally representative.

Part of your book explores the roles women have played in Islamic architecture history. What did you discover?

Islamic architecture history is very male-oriented. But, sometimes, in doing research, I found that the influence of a mother of a ruler, or a wife, or a sister will be mentioned. There are so many of these interesting stories that I decided it merits highlighting in a special chapter. It’s not always just men who’ve been doing something.

Who have been some of the most recent influential architects?

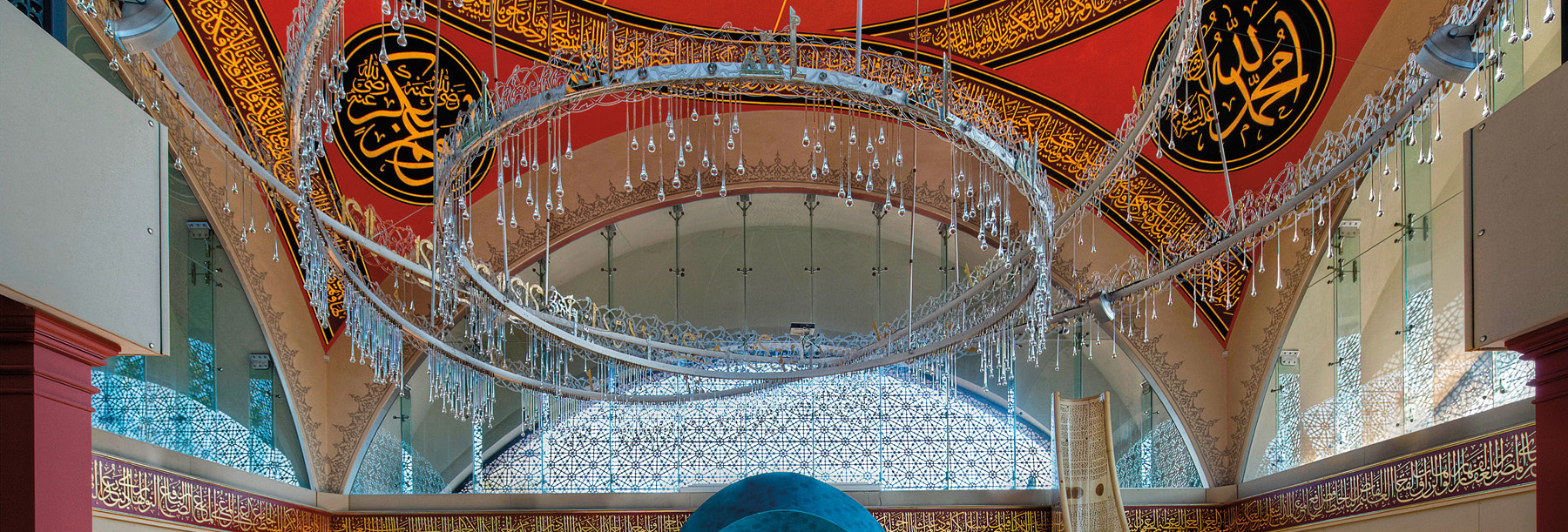

Zaha Hadid designed the prayer space—musalla—of the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, in Riyadh—a wonderful building. And Zeynep Fadillioglu became the first woman to design a mosque interior when she created the interior of the Sakirin Mosque, in Istanbul.

How do you see Islamic architecture evolving today in the Middle East?

The countries in the Gulf are looking in more depth to their own visual heritage and not just using geometrical patterns. You see that in Saudi Arabia and in the UAE, in particular.

Modern architects sometimes draw on various aspects of Islamic architecture for inspiration. Do you have any concerns about that?

What troubles me is the way geometric patterns are used in contemporary architecture because quite often they’re added to an exterior or to a floor to add a little bit of “Islamic flavor” to a building. Traditionally these patterns are meant to engage with the passersby, to invite people to reflect. It would be wonderful if that element of engaging with the people could be taken into consideration in contemporary architecture.

What do you have in mind as your next project?

It’s funny because every time I finish something, I think I’m done. After I completed my first book, Islamic Geometric Patterns, I thought that was it; God’s plan fulfilled. But then I was given the opportunity to write two more books on the same subject, much to my amazement. Again, I thought, surely this is the plan for me fulfilled. So now, I have written this book, and I make no more claims to know what His plan is for me.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

You may also be interested in...

Handmade, Ever Relevant: Ithra Show Honors Timeless Craftsmanship

Arts

“In Praise of the Artisan,” an exhibition at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, aims to showcase Islamic arts-and-crafts heritage and inspire the next generation to keep traditions alive.

Spotlight on Photography: Drinking in Türkiye’s Coffee Culture

Arts

‘Home’: Arab American National Museum Celebrates 20th Anniversary

Arts

Arab American National Museum Director Diana Abouali says the facility—which is marking its 20th anniversary in 2025—in Dearborn, Michigan, has aimed to create a home for Arab Americans by preserving and presenting the history, culture and contributions of Arab immigrants as well as their native-born children and grandchildren.