Tapping Into Andrew Nemr's Story: Exploring Art and an Artist’s Motivation

Art

Levant

Americas

Explore how dancing and storytelling open opportunities for communication among people.

The following activities and abridged text build off “Andrew Nemr Taps Into Story,” written by Ken Chitwood and photographed by Bear Gutierrez.

WARM UP

Scan the article’s photos and captions to predict its theme and main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Watch a video of Andrew Nemr describing how he became interested in tap dancing. Then discuss the main points of the video and Andrew’s philosophy of life and art.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Engage in an “inside/outside discussion activity” to gain a broader understanding of Andrew Nemr and his philosophy of life.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Play the role of a magazine editor, formulate a caption for a photo and create a gesture drawing to accentuate the action and energy of the photograph.

Directions: As you read, you will notice certain words are highlighted. See if you can figure out what these words mean based on the context. Then click the word to see if you’re right.

Andrew Nemr Taps Into Story

Sweat beads Andrew Nemr’s face as he glides and clacks on his portable performance stage. Sound reverberates from his tap shoes. But he’s not just dancing; he’s also talking, telling a story. It’s 2017, and his one-man production, Rising to the Tap, combines tap dance with storytelling.

His subject: life, and our journeys to discover purpose, across continents, among cultures and over time. In dance, he tells his own story. It begins at his birth in 1980 in a suburb of Edmonton, Alberta. He takes his audience from that small town and builds toward an understanding of his identity within cultural, national, and religious contexts.

Five years later, Nemr is still performing Rising to the Tap. As he has evolved, so has his show.

Nemr’s parents fled the Lebanese Civil War before he was born. But their memories are part of his story. In his show, he shares those memories in images of black smoke and bombed-out buildings in Beirut. These images are framed by family discussions of a Lebanon that was.

At the family dinner table, Nemr remembers his father, Joseph, telling stories from Lebanon’s past. “Even though I didn’t have personal connections to some of these stories, the relationship to Lebanon was evident,” he says.

Question: Why does Nemr begin the story of his life before his birth?

Because his own life was shaped by his parents’ experiences.

Question: Why does Nemr think of stories about Lebanon as part of his story?

Because he believes his story is both individual and communal. Lebanon’s history is part of his history.

Nemr says his parents never framed their own lives in terms of the war that had forced their emigration. Nonetheless, “it does something to a kid when you turn on the TV … and there are pictures of the place where your parents are from being bombed,” he says. “I could see that my parents were feeling the pain of the war.”

When he was 3 years old, the family moved to the United States, just outside Washington, D.C. Soon after arriving he enrolled in his first dance class. At age 9 Nemr recalls he “fell in love” with tap dance. He was inspired by the 1989 movie Tap, which starred Gregory Hines and Sammy Davis, Jr. Most compelling was the film’s “challenge dance” scene, which featured several tap legends.

“They were so free, so expressive, so in tune with themselves and the tap,” says Nemr. “I wanted to be like them.”

Nemr would later be mentored by Gregory Hines, one of the most-celebrated American tap dancers of all time. Nemr studied under Hines in New York at Woodpecker’s Tap Center, honing what Hines called Nemr’s “rich and truly expressive” skills.

It was at Woodpecker’s that Nemr also met New York tap dancer, actor and renowned dance mentor Savion Glover. Later he joined Glover’s DC Crew, then helped found Glover’s dance company. He danced alongside and studied under some of the world’s best tap dancers. These dancers, he says, became his “gateway into the oral tradition of the craft. They mentored me not only so I could share their steps but also share who they were.”

For Nemr, dance has always been about the collective and the wider story of traditions and peoples sidelined, put down by injustice or chased by conflict.

“I am one person, but there are tons of other ‘one persons’ around,” he says. “I was grafted into a kind of communal story in which you begin to parse out your place. It goes beyond performance or learning a craft.” Dancing, says Nemr, “if it’s done well, it tells a story: something historical, something commonplace or something that is both at the same time.”

Question: What “communal story” is Nemr talking about here?

He is talking about the stories of other dancers.

Viewing dance that way puts Nemr in a class by himself. Contemporary US artist Makoto Fujimura once described Nemr as “one of the greatest tap dancers of our time” and perhaps “even greater of an artist.”

As a TED Fellow, Nemr has explored how digital technology can help oral traditions survive in changing times. In a talk entitled “Stepping Back in Time Before It’s Too Late,” Nemr related how his emergence into the tap-dancing scene in the US enabled him to become a carrier of its oral tradition, a raconteur of its “good ol’ days” and a chronicler of its 1990s reemergence into the national psyche.

When he speaks about oral traditions in workshops or courses, Nemr says, he reminds his students that until recently, each generation did not have its own styles of music. Music was passed down through generations. Music and dance reinforced the identity of the individual within the story of the community. In a world where every person can curate a unique soundtrack, that communal aspect of music and dance could easily be lost, he says.

Question: According to Nemr, how are music and dance both individual and communal?

They are made by individuals but they are shared across generations and among other people.

“In ‘tap-dance land,’ you learn this thing that you do from people, shaped in part by who they are and their personalities. And as you learn from them, you begin to embody someone else’s personality, someone else’s story—their choices, preferences, approaches to excellence, relationship to the audience, music. And then you can begin adding your own and passing it on,” he says.

It is, as he often tells his students, in these larger stories that one can really find oneself and, perhaps, make the world a better place.

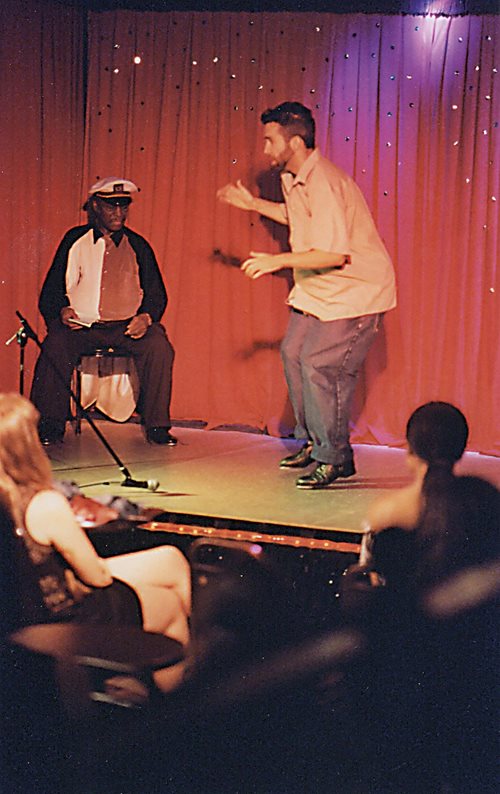

courtesy andrew nemr / tap on barcelona / basilio gonzález

At the 2019 international event Tap on Barcelona, Nemr put on a workshop and performed.

In 2004 Nemr founded his own dance company, Cats Paying Dues. It won critical acclaim with its focus on the ensemble rather than the individual. It also eventually brought Nemr into contact with Jim Dolle, branch director at McBurney YMCA in Brooklyn, New York. In 2016, Dolle watched Nemr perform his mix of tap and spoken word, and a vision began to form in Dolle’s mind.

“I saw Andrew as a catalyst…able to build bridges between different communities in New York City—performers, artists and people of faith,” Dolle says. Nemr became a regular instructor, coach and performer at the YMCA.

“Andrew’s power comes from his ability to cross genres and to connect with people of various backgrounds,” Dolle says. “He can relate different cultures together, where you would not necessarily think there is a natural similarity. “His universal, unique expression through tap—his style—is able to cross boundaries in ways that other forms of storytelling maybe can’t.”

courtesy windrider institute

A screen shot from the film Identity: The Andrew Nemr Story shows Nemr performing on the streets of Tokyo. The documentary film unpacks the complexities of Nemr’s life-journey with tap dancing.

Dolle also says Nemr “brings an interesting mix of heritage and personal experience that shows how circumstances in life are not that simple.”

Nemr describes some of his stories as not just narratives but homilies. They are instructive tales and invite the audience into both wider wonder and compassionate understanding.

“The stories that we tell can either breathe life into someone, or death,” Nemr says. “As a storyteller, there’s a lot of power there. And with a lot of power comes a lot of responsibility.”

That, he adds, requires a firm foundation. For himself, that means always landing in the same place: love.

“Over the course of my life, I experienced significant disappointment and pain, as relationships fell apart on account of things I had no control over. Other peoples’ lives are the same. The question is whether you allow a seed of bitterness to be planted and grow … or try to water the seed of love that is there even in the midst of that pain.”

That, he adds, is “the kind of story the world needs to hear more.”

Other lessons

Aramco World Learning Center: No Passport Required

For the Teacher's Desk

Project-based learning lies at the heart of AramcoWorld’s Learning Center. Link its resources into classroom curriculum, no matter the subject.

The Legacy of Borchalo Rug-Weaving in Georgia: Explore Cultural Change Through Critical Reading and Design

Art

History

Anthropology

The Caucasus

Analyze efforts to preserve a centuries-old weaving tradition, and connect the Borchalo story to questions of identity, memory and heritage.

Visualizing From Where Food Comes: Teaching Environmental and Social Impacts of Global Farming

Environmental Studies

Geography

Examine global food production through George Steinmetz’s aerial imagery and evaluate how farming affects people, ecosystems and sustainability.