Saving Sarajevo’s Literary Legacy

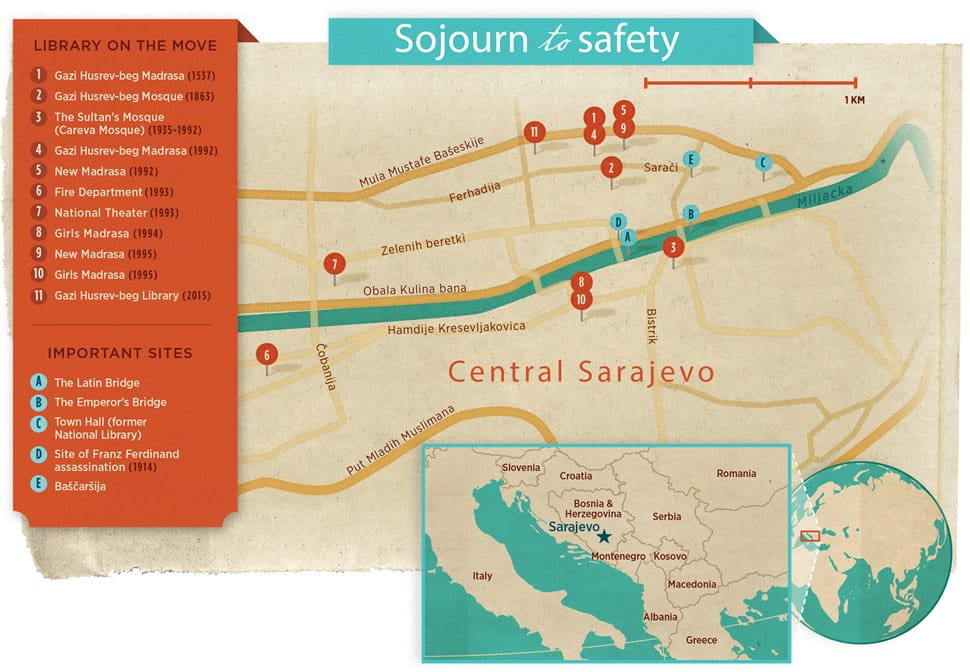

Braving sniper bullets, Mustafa Jahi and friends carried the historic volumes of the Gazi Husrev-beg Library from one hiding place to another throughout the three-year Siege of Sarajevo. Last year, the library found a new, permanent haven—close to where it was founded nearly 500 years ago.

In the autumn of the year 1521, Gazi Husrev-beg, the newly appointed governor of the Ottoman province of Bosnia, rode at the head of a detachment, fresh from Istanbul, bound for the provincial town of Sarajevo, on the banks of the Miljacka River.

The appointment was a gift to the 41-year-old general from his cousin, Sultan Suleiman i (“the Magnificent”), who regarded Husrev-beg (Hoos-rev-bey; the suffix beg is an honorific, akin to the English “Sir”) as one of his most trusted military officers and diplomats.

The new governor likely entered Sarajevo across a stone bridge over the Miljacka, just east of the Careva Džamija or Sultan’s Mosque, among the first structures built by his predecessor and Sarajevo’s founder, Isa-Beg Ishaković (ih-sha-ko-vich). Creaking along behind, packed among his wagonloads of possessions, were Husrev-beg’s many books and manuscripts, some of which he ultimately bequeathed to posterity. In time, his bequest would grow into the largest library of Islamic manuscripts and documents in the Balkans, the most extensive collection of Ottoman manuscripts outside of Turkey and one of the largest libraries of its kind in all of Europe.

Sarajevans walk north across the Emperor’s Bridge, the same route Jahić and his team took under the guns of snipers. The Sultan’s Mosque, the library’s home from 1935 until 1992, stands in the background.

Nearly five centuries later, in 1992, the latest in the line of scholars to whom Husrev-beg had entrusted his legacy, Mustafa Jahić, then director of the library, warily approached the southern end of the landmark bridge together with a handful of colleagues. Clutching boxes filled with the library’s precious collection literally and figuratively close to their hearts, they calculated their chances of making it across the river alive. In the buildings and hills around them, Serb snipers waited to train crosshairs on anyone drifting into the exposed thoroughfares that became known during the 1992-1995 Siege of Sarajevo as “sniper alleys.” If they made it today, they would do it again. And again, over the next three years, throughout the besieged city.

Jahić and his colleagues were willing to take those risks to preserve part of the surviving cultural heritage of their city and newly declared country. Established in March 1992 following the breakup of multi-ethnic Yugoslavia, Bosnia-Herzegovina had turned almost immediately into a battlefield. In Sarajevo, both Muslim Bosniak and Catholic Croatian populations found themselves targets of Orthodox Serb nationalists supported by neighboring Serbia. In addition to claiming the lives of nearly 14,000 in Sarajevo alone—5,400 of whom were civilians—the Serb militia also systematically attacked Bosnia’s cultural identity: by August 1992, two of Sarajevo’s top libraries, the National Library and the Oriental Institute, had been reduced to cinders.

Jahić was determined to save Gazi Husrev-beg’s legacy from the same fate. With the help of others who shared his devotion to the library and commitment to Bosnia’s intellectual history, the dedicated librarian led the spiriting of the collection from one hidden location to another throughout the war until, in 2014, it ultimately came to rest in a brand-new and secure building just steps away from the site of the original library established by Gazi Husrev-beg.

This is their story: Of one man who regarded books and knowledge as essential legacies and of another who risked his life to preserve them both.

The year Gazi Husrev-beg took up his governor’s residence, Sarajevo was classified in Ottoman records as a kasaba, meaning it was bigger than a village but smaller than a šeher, or city. Founded by Ishaković around 1462, it lay within the boundaries of the medieval Bosnian kingdom of Vhrbosna, conquered by the Ottomans a decade earlier. Though well sheltered by surrounding mountains and well watered by the Miljacka, at the same time the city was potentially vulnerable to aggressors who could scale those selfsame mountains encircling the valley town. Still, its strategic location, within marching distance of “the empire’s shifting boundaries with Venice and the Hapsburg Monarchy,” as historian Robert J. Donia observed, made it an increasingly important commercial, administrative and military center for Ottoman expansion into “Rumelia”—the Balkans.

—Mula-Mustafa Ševki Bašeskija

Ljetopis o Sarajevu 1746-1804 (Chronicle of Sarajevo)

The city was named after the saraj (sar-eye), or royal court, Ishaković erected on the south side of the river near a large ovaši (oh-vah-shee), or field, and hence Sarajevo, a Slavic contraction of Sarajovaši. The founder also built a fortification on a rocky outcrop to the east, the city’s natural gateway where the Miljacka chisels its way through the mountains. Crumbling remains of this stone fortress, together with later Ottoman-era defenses, still dot the city’s forested highlands like broken teeth.

It was Gazi Husrev-beg who would, over 20 years, help grow Sarajevo into a šeher. It was a job the middle-aged diplomat-general was bred for. Born in Seres, Greece, in 1480, Husrev-beg was the son of the local Ottoman governor, the Bosnian-born Ferhad-bey, and a Turkish mother, Sultana Selçuka, daughter of Sultan Beyazid ii. His mother’s royal connection made him first cousin to Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. During his tenure as governor of the eyalet (province) of Bosnia—which comprised territory roughly equivalent to today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina—Sarajevo grew into the empire’s third largest European city after Salonica and Edirne. The era has been called Sarajevo’s “Golden Age.”

By way of transforming the provincial capital into an “expression of Ottoman civilization,” as Donia put it, Husrev-beg used the Empire’s basic blueprint for growth: Divide it into residential neighborhoods, called mahalas, with a house of worship at the center of each. Prior to Husrev-beg’s arrival, Sarajevo had only three Muslim mahalas; under his administration, that number increased to 50. By the early 17th century, there were nearly a hundred, together with a small number of Christian and Jewish mahalas in the decidedly interfaith city.

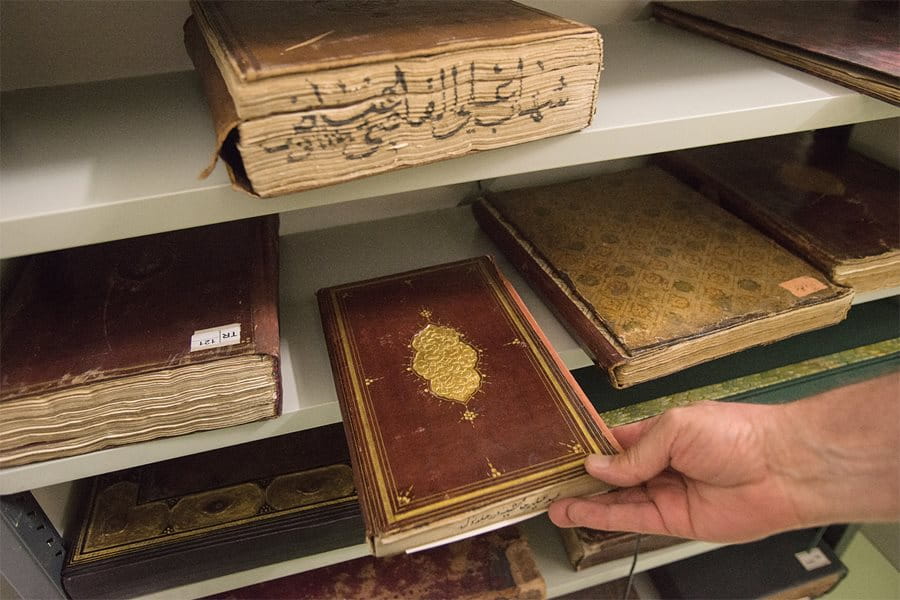

Above: Beautifully bound books with embossed leather covers, dating back several centuries, are numerous within the Gazi Husrev-beg Library’s 25,000-volume collection. At its heart are books that Gazi Husrev-beg brought when he arrived in Sarajevo as governor of Bosnia (today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina) in 1521. Below, right: Lejla Gazič, former director of Sarajevo’s Oriental Institute, watched helplessly as its books burned after Serbian nationalists firebombed the Institute the night of May 16, 1992. She still struggles to understand why they attacked the library.

The heart of Sarajevo’s commercial and cultural activity was the Baščaršija (bahsh-char-see-yah), or marketplace, just north of the river. Both Ishaković and Husrev-beg built bezistans (covered bazaars) here, and to this day it remains the city’s most popular pedestrian thoroughfare. Retaining much of its Ottoman-era flavor, the Baščaršija offers browsers everything from Bosnian soccer jerseys to Persian carpets, as well as post-siege novelties such as ballpoint pens fashioned from spent bullet cartridges harvested from the streets. At five city blocks long, Gazi Husrev-beg’s bezistan is the largest of all.

In Ottoman times, traveling merchants stayed in hans, which were also called karavan-saraj (caravanserai). Essentially business hotels, they featured central courtyards for unloading and stabling pack animals and rooms above where the merchants enjoyed free meals and lodging for a maximum of three days. Many hans survive today as restaurants, including the colorful Morica Han—built by Husrev-beg. In the han’s tree-shaded courtyard, tourists now sip tea or milky, beige-colored Bosnian coffee and chat with the easygoing rug and ceramics merchants operating out of the historic structure’s converted stables.

Most of the city’s cultural, economic and religious institutions—its mahalas, mosques and hans—were supported by charitable endowments known as vakuf, which is a Bosnian adaptation of the Arabic waqf. Vakufs were endowed by wealthy patrons, many of whom were high-ranking military officers like Husrev-beg who amassed fortunes (some might say loot) after years of campaigning. Of all of Bosnia’s vakuf, Husrev-beg’s was the wealthiest and most extensive. In addition to mahalas, hans and bezistans, the governor endowed a hammam (bathhouse), a imaret (soup kitchen), a haniqah (a Sufi study center) and a madrasa (school) that he named Seljuklia, after his mother. (Because its roof was made of lead—kuršum in Turkish—it became known locally as Kuršumlija, and it remains the oldest surviving madrasa in Bosnia and Herzegovina.)

At the center of it all, Husrev-beg erected a mosque that now bears his name. Elegant with its slender minaret, multi-domed roofline and clock tower, it is the largest historical mosque in Bosnia and Herzegovina, reputed to be the finest example of Ottoman Islamic architecture in the Balkans. Rising from the heart of the Baščaršija, it stands as a symbol of the city and a focal point for Sarajevo’s—and indeed all of the country’s—Muslim community, which comprises some 40 percent of the country’s population today. (Orthodox Christians follow at 31 percent; Catholics at 15 percent.)

Thus it was that under Husrev-beg’s governorship, Sarajevo became an urban reflection of the governor’s belief in the enduring virtue of vakuf.

To the east of the new Gazi Husrev-beg Library, which opened in 2014, lies the library’s first home, in the 16th-century mosque-and-madrasa complex built by Husrev-beg. The hills surrounding the city, which held snipers during the Siege of Sarajevo, are today a postcard backdrop to Sarajevo’s old city.

“Good deeds drive away evil, and one of the most worthy of good deeds is the act of charity, and the most worthy act of charity is one which lasts forever,” Husrev-beg declared in his vakuf’s endowment charter, preserved in the archives of the modern Gazi Husrev-beg Library.

With these principles in mind, in 1537 Husrev-beg also decreed in the charter of the school that “whatever money remains from the costs of construction be used to purchase good books to be used in the said madrasa, that they be used by those who will read them and that transcriptions be made from them by those who are involved in study.”

Books purchased under these terms, along with manuscripts Husrev-beg donated, comprised the library at its founding, and it grew quickly. Amid its increasingly notable collection were well-known works on philosophy, logic, philology, history, geography, Oriental languages, belles-lettres, medicine, veterinary sciences, mathematics, astronomy and more. Some were donated (including entire private libraries); many more were transcribed, per Husrev-beg’s directive, by copyists working in the whitewashed cells of the madrasa and haniqah. Meanwhile, just a few meters away, in Mudželiti (moo-zhel-ee-tee) or Bookbinders Street, what began in the 1530s as a clutch of small bindery shops blossomed into a full-blown bookseller’s bazaar, reflecting Sarajevo’s growth as one of the Ottoman empire’s most prolific literary and intellectual centers.

“In these religious complexes, rarely was it only just a mosque. It was usually a number of buildings, and some of them, from the very beginning, had an educational purpose,” observed Ahmed Zildžić, a scholar at the Bosniac Institute, a research center for the study of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s cultural past headquartered in the beautifully restored and repurposed Gazi Husrev-beg hammam. “So there was either a side-library or a little maktab (office), which is like a [Christian] Sunday school, that introduced literacy to Slavic converts to Islam who then started to acquire literacy in Oriental languages,” he said.

Taking full advantage of the Pax Ottomana’s far-flung resources, some of these promising young scholars fanned out across the empire to study in its famed centers of scholarship: Istanbul, Damascus, Beirut, Cairo, Baghdad, Makkah, Madinah and more. Returning to Bosnia, they brought with them still more books and manuscripts, in Arabic, Ottoman Turkish and Persian, all of which enriched the country’s literary heritage and its libraries including Gazi Husrev-beg’s. Books and manuscripts were also acquired through trade or were brought back by individuals completing the Hajj, or pilgrimage to Makkah. Many times, these imported works were translated into Bosnian, while local scholars also began producing more of their own uniquely Bosnian Islamic scholarship: treatises and commentaries on Arabic philology, Islamic law, the Qur’an, etc., composed in their native language. And as this corpus grew, so too did Sarajevo’s reputation as a repository for Bosniak culture and “one of the most significant cultural and scholarly centers of Rumelia,” said Zildžić.

Certainly, 1992 was not the first time these literary treasures came under threat. Punching his way into Bosnia in 1697, Hapsburg prince Eugene of Savoy vowed to “destroy everything with fire and sword,” including Sarajevo, unless it surrendered. True to his word, as he recorded in his military diary, “[w]e let the city and the whole surrounding area go up in flames.” These “Austrian infidels,” as one anonymous Sarajevan reported, seemed especially bent on destroying the city’s Islamic institutions: “[T]hey burned books and mosques, ravaged mihrabs [prayer niches in mosques] and the beautiful Šeher-Sarajevo, from one end to the other.”

In the late 19th century, a citywide fire razed many buildings, and this literally cleared the way for German architects to remake Sarajevo in the image of the Austro-Hungarian Empire during its roughly 33-year rule that began in 1885 under Emperor Franz Joseph i. (One stylistic exception to this early modernism was the city’s Moorish Revival town hall, completed in 1894, which later became the National Library.)

More famous than burning books during this era was the assassination, on June 28, 1914, at the foot of the Latin Bridge just a few meters west of the Emperor’s Bridge, of Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg. The incident ignited the First World War, which ironically largely spared Sarajevo, though the city fared less well in World War ii, when it suffered both German and Allied bombing.

Meanwhile, through it all, the Gazi Husrev-beg Library continued to grow, to the extent that it had to move to expand, twice prior to the Second World War. The first move was in 1863, across the street to a purposefully built room at the base of the Gazi Husrev-beg mosque’s minaret. By 1935, the library outgrew this space, too, and was relocated across the river to a room in the basement of the mufti of Sarajevo’s office, next to the Sultan’s Mosque. Eventually, the mufti—the city’s foremost Islamic scholar—vacated the whole office building to accommodate the growing collection.

To ferry books from one "library safe house" to another during the siege, Jahić and his companions frequently used banana boxes, then as now a common method of storing and transporting books in Sarajevo's open-air book market.

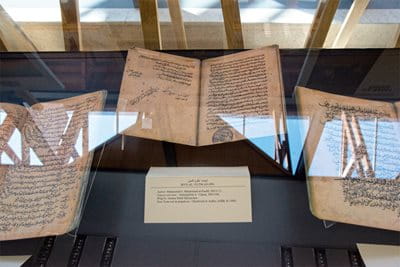

By the early 1990s, the Gazi Husrev-beg Library had become one of the most valuable in the Balkans, with some 10,000 manuscripts in Arabic, Persian, Ottoman Turkish and Bosnian Slavic written in Arabic script, known as arebica or aljamiado. Its oldest and most precious manuscript remains a copy of al-Ghazali’s Ihya’ulum al-din (The Revival of Religious Sciences), produced during the author’s lifetime in 1105. Another treasure is the Tufhat al-ahrar (The Gift to the Noble), a didactic poem by the 15th-century classical Persian writer Nur al-Din ‘Abd al-Rahman, penned in exceptionally beautiful calligraphy in Makkah in 1575. Also significant are the library’s decoratively bound copies of the Qur’an, which served as templates for copyists. Many of these beautifully produced volumes, encased within embossed leather covers, featured richly illuminated pages with calligraphy and border decorations in azure, gold and brick-red ink.

Among its 25,000 books are the oldest printed works (from the mid-18th century) by some of the most prolific Bosnian authors writing in Oriental languages as well as the oldest in the Bosnian language, together with several of the earliest books produced by Hungarian-born Ibrahim Müteferrika, who in his lifetime from 1674 to 1745 became the first Muslim to operate a printing press using moveable Arabic type. The library’s periodical collection includes Bosnia’s oldest newspapers as well as nearly all Muslim newspapers and journals, current and historic, published in Bosnia, including a nearly complete set of Bosna, the eyalet’s official newspaper from 1866-1878. In addition, there are some 5,000 Ottoman firmans (royal decrees) and berats (charters); local sharia court registers known as sijjils; defters (tax records); as well as photographs, leaflets and posters.

“Census books, tax books, government records: These are indispensable sources if you want to study the history of any religious or ethnic groups in the Balkans, not just Muslims,” said Zildžić.

Adding to these invaluable resources, prior to the Bosnian War, were the collections of the National Library and the University Library of Bosnia Herzegovina, just up the river in the former city hall, and the nearby Oriental Institute, founded in 1950. Together these two institutions housed some two million volumes, 300,000 original documents and 5,263 codices (bound manuscript collections). Along with the Gazi Husrev-beg Library, this entire, precious cache, the body if not the soul of Bosnia’s cultural and intellectual heritage, lay concentrated inside a few square kilometers of the city, open to attack. Keenly aware of this vulnerability, Jahić preemptively moved the Gazi Husrev-beg collection from the mufti’s offices back across the river to its original home, the Kuršumlija, where he thought the books would be safer.

Above: Sarajevo remains a city of bibliophiles. Here, residents and visitors browse at a Ramadan book fair. Below, right: Tourist souvenirs brighten a window in a bezistan (bazaar) shop in the Baščaršija, Sarajevo’s commercial and cultural center.

His decision was prescient. On the night of May 16, 1992, the attack came, within blocks of the Sultan’s Mosque.

The firebombing of the Oriental Institute that night was the opening salvo of a war not only against people, but also against their very thoughts, ideas and cultural identity. Seeking to create a unified, monoethnic state from the rubble of post-Communist Yugoslavia, Serbian nationalists were determined to wipe out Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Bosniak and Croat culture.

The three-year Siege of Sarajevo was to become the longest siege of a capital city in the history of modern warfare. Taking up positions in its surrounding mountains, Serbs firebombed Sarajevo night and day. During lulls in the bombing, snipers watched and waited to pick off pedestrians who emerged from the chaos, desperate for food, water and fuel. Signs reading Pazite, Snajper! (“Beware, Sniper!”) were plastered about like wallpaper. So willfully focused on the eradication of culture was the Serb aggression that philosophy professors at the university were identified as prime assassination targets. So, too, were their writings and those of their cultural predecessors. “The Siege of Sarajevo,” observed Bosnian scholar András J. Riedlmayer a decade after the conflict, “resulted in what may be the largest single incident of deliberate book-burning in modern history.”

On the morning of May 17, as the Oriental Institute still smoldered, former director Lejla Gazič rushed to the scene, hoping to salvage what she could, but firefighters blocked her. Not only was the building unstable, but it remained a target, as Serbs were shooting at the firefighters. Recalling that terrible day, Gazič still struggles to fathom the event.

“People kill people in wars, I understand this,” she said. “But if you kill books, that is something you cannot imagine. Books are a common heritage for everybody, everywhere. How can somebody kill the books?”

Yet the unimaginable got even worse. Three months later, Gazič and her fellow Sarajevans again watched in horror as, an hour after nightfall on August 25, Serb forces immolated the National Library with a barrage of phosphorus bombs. As they had during the destruction of the Oriental Institute, Serb fighters in the hills “peppered the area around the library with machine-gun fire, trying to prevent firemen from fighting the blaze,” according to Associated Press reporter John Pomfret, who was on the scene. Nevertheless braving the sniper fire, librarians and citizen volunteers formed a human chain, passing what books they could gather out of the burning building. But when the heat exploded the structure’s slender Moorish columns and the roof came crashing in, it was too late: The library’s invaluable collection was gone.

“The sun was obscured by the smoke of books, and all over the city sheets of burned paper, fragile pages of grey ashes, floated down like a dirty black snow,” one librarian later recalled. “Catching a page, you could feel its heat, and for a moment read a fragment of text in a strange kind of black and grey negative, until, as the heat dissipated, the page melted to dust in your hand.”

Asked by Pomfret why he was risking his life against such odds, fire brigade chief Kenan Slinič—“sweaty, soot-covered and two yards from the blaze”—said, “Because I was born here, and they are burning a part of me.”

Jahić understood this intense devotion. Thirty-eight years old at the start of the war, he had been on the job as director of the Gazi Husrev-beg Library for five years when the siege began. Throughout the ordeal, he dutifully made his way back and forth every weekday between the two loves of his life: his wife and children, and the library. It was a perilous commute. His house stood a mere 500 meters from Serb lines, and his family was forced to hide in the basement for most of the day. To minimize the risk of sniper fire along his seven-kilometer journey each way, he snaked through graveyards, crouching for cover behind the broad, flat headstones of the Christian sections, which provided better cover than the slender Muslim headstones.

Strollers throng Sarači Street, a pedestrian thoroughfare in the Baščaršija that runs east-west through hundreds of years of the city’s history. The new Gazi Husrev-beg Library, and its original location at the Kursumlija, are nearby.

Committed to his job and to maintaining as normal a life as he could under the circumstances, Jahić kept the library collection available to scholars as long as possible. Yet he knew that the Serbs knew where it was, which is what prompted him to move the collection in the first place. After the destruction of the Oriental Institute and the National Library, he knew he had to keep the collection on the move, if it was to be spared the same fate.

“I knew that the Serbs’ agenda was to completely destroy the cultural heritage of Bosnia,” said Jahić. “So in order for the enemy not to know the location of the library, I contacted friends and other librarians and had them help me physically move the collection from one location to another throughout the war.”

From 1992 to 1994, Jahić and his faithful, dedicated colleagues—including a volunteer from the library’s cleaning staff and a night watchman—moved the collection a total of eight times, changing locations every five to six months. For the duration of the conflict, Jahić placed the most valuable items, such as the al-Ghazali and other rare manuscripts, in the vault of the Privredna bank near the center of town. But the bulk of the collection he and his colleagues carried by hand, from place to place, usually in cardboard banana boxes, like college students moving in and out of a dorm.

The first hiding place was the library’s original home, the Kuršumlija. This was followed by a move next door, to the larger, “new” madrasa, built during the Austro-Hungarian period. It was moving the books to these locations, back across the river over the Emperor’s Bridge, that was one of the most dangerous, said Jahić.

“This bridge was open to snipers up there in Trebević,” he said, glancing up at the rocky highland from the middle of the bridge.

Next, an influx of refugees from the surrounding area requiring shelter in the madrasa compelled Jahić to move the collection again, to the dank bowels of the old fire department barracks where it languished for several months in a disused, subterranean firing range—hardly an ideal setting for rare books. Still, Jahić knew he had to use whatever resources he could to stay one step ahead of the Serbian militia. Two more moves followed in 1993: to the dressing rooms of the National Theater, and then to the classrooms of a girl’s madrasa not far from the fire department barracks. All the while, Jahić was thinking even further ahead of his enemy’s intentions.

While the library seemed to be relatively safe for the time, he realized that it could yet go up in flames at any moment. So to ensure its intellectual if not physical contents, he began microfilming the entire collection. While this might sound like a daunting project even during the best of times, Jahić had to cope with infrequent electricity, no running water for film processing, no real proper equipment nor knowledge of how it worked once he got it—all the while under enemy fire. A lesser librarian might have faltered or never started. But Jahić, energetic and resourceful, fully grasped what was at stake and, like many an insurgent before him, resorted to the underground.

“We arranged to have microfilm equipment smuggled in through the tunnel,” said Jahić, referring to the 700-meter, hand-dug tunnel beneath the Sarajevo airport. During the war, this narrow passageway, just one meter by one meter, running from a private garage to the suburb of Dobrinja, proved a lifeline that channeled food and supplies to Sarajevo’s 400,000 besieged citizens, and provided the only safe escape route out of the city.

With the help of a local microfilm technician and his hired crew, Jahić commenced photographing as best he could. In spite of all odds, the team managed to microfilm 2,000 manuscripts during the war.

“It was a problem because there were frequent blackouts and no electricity, so we used car batteries to supply power whenever the electricity went out,” Jahić recalled. The water they required they drew from the Miljacka. All the while, such resources were dwindling.

“Food, water and wood. These were the three most important things during the siege,” said Jahić, recalling that luxuries like the library’s wooden bookshelves were among the first items to be seized by people for kindling during the crisis, followed by the trees in every park in the city, transforming them into vast, empty fields of stumps.

Left: A conservator works on restoring a document in the library’s book-preservation lab, part of the expanded, nine-million-dollar library complex that rose, phoenix-like, after the siege, to open last year. Right: Display cases include this facsimile of the library’s oldest manuscript, Al-Ghazali’s The Revival of Religious Sciences, produced during the author's lifetime in 1105.

Relocating the books themselves was also risky and not only because of snipers. On one occasion, while scuttling through the bombed-out streets with their banana boxes filled with books, Jahić and his crew encountered a pack of young men. The gang accosted them, thinking they were hoarding a load of bananas, an exotic luxury at a time when such basics as bread were at a premium.

“But when they looked into the boxes and saw that they were just books, they threw them to the ground and went on their way,” Jahić recalled.

Certainly neither Jahić nor his crew had signed up for confrontations with street gangs. But like the firefighters waging their losing battles against burning buildings, they viewed what they were doing as not only their patriotic duty, but their obligation to humanity.

“Of course it was worth risking my life for,” said library night watchman Abbas Lutumba Husein later to the producers of the 2012 BBC documentary “The Love of Books: A Sarajevo Story.” An immigrant born in Congo, where he grew up amid violence and conflict, Husein said his life had been transformed by reading the Qur’an. During his night shifts at the library, he took comfort in reading its books, sensing the presence of their authors and feeling at peace among them. The library, he said plainly, “saved my life.” He would have preferred, he concluded, “to die together with the books than to live without them.”

A family prepares to break the Ramadan fast with a picnic at Sarajevo’s old Yellow Fortress, north of the Miljacka River, while other city residents take in a tranquil sunset panorama.

When the siege ended in 1995, the library was back at the girl’s madrasa, and Jahić continued to work on digitizing, microfilming and cataloguing its entire content to preserve it and minimize the threat of its destruction ever again. The cataloguing was completed in 2013 and published with the support of the London-based al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation. Now, the most important items in library’s collection are completely digitized.

In the early 1990s, discussions had already begun about the creation of a new building to house the library’s continually growing collection, but had to be postponed because of the war. Eventually, an architect was commissioned (see sidebar, opposite), and in 2014 the new Gazi Husrev-beg Library opened, thanks to a major donation from the government of Qatar. The glittering, three-story glass-and-marble structure, opposite the site of the original library, holds storage for 500,000 volumes, reading rooms, a conservation room and a 200-seat auditorium with WiFi-connected headsets in every seat for simultaneous translation of up to three different languages. In the basement, there is also a museum dedicated to Bosnia’s history of literacy.

Yet at the heart of the high-tech structure are the books, all of them, which Jahić, now a resident scholar, regards almost as dearly as his own children.

“During the war, I was trying to save both my family and the library,” he said. “In the process, I came to love the books very much. It is difficult for me to speak about them now without great emotion.”

About the Author

Boryana Katsarova

Boryana Katsarova is a freelance photojournalist represented by the Paris-based Cosmos Photo Agency. She lives in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Tom Verde

Tom Verde (tomverde.pressfolios.com) is a senior contributor to AramcoWorld. Like the majority of those who responded to a 2015 global survey, his favorite color is blue.

You may also be interested in...

AramcoWorld Explores Universal Food and Cross-Cultural Identity

Food

History

Nakshi Kantha Embroidery: Tales of Heritage and Revival

Arts

History

A traditional form of quilting in Bangladesh in which women embroider family history, love and memory into the fabric is blanketing markets locally and beyond.

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.