The Place of Many Fish

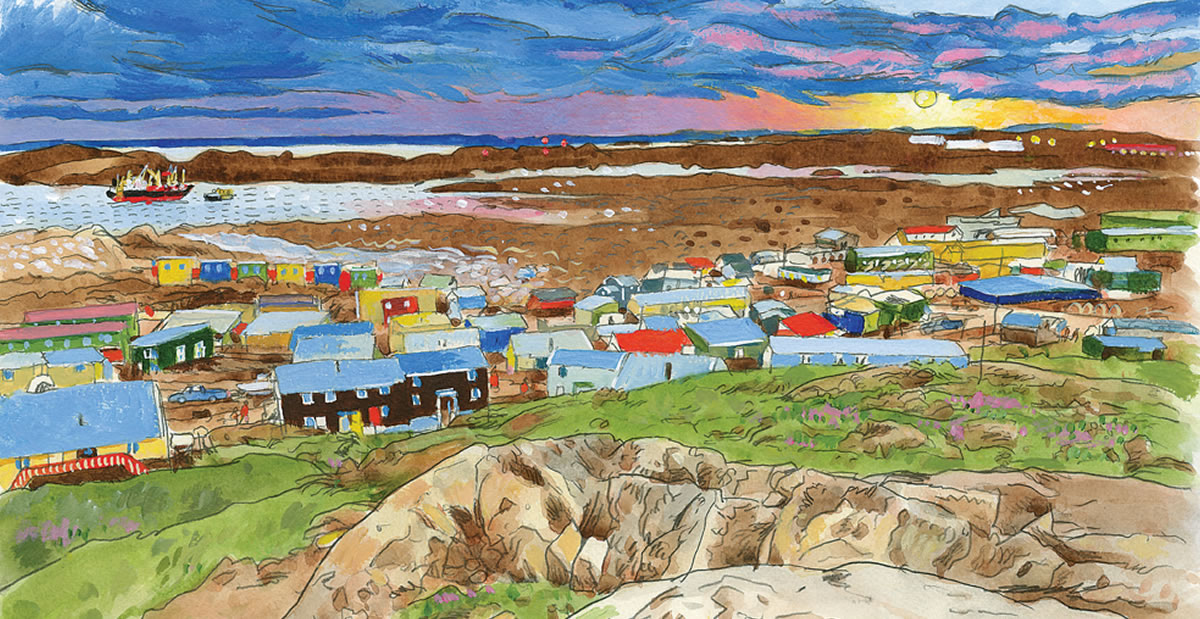

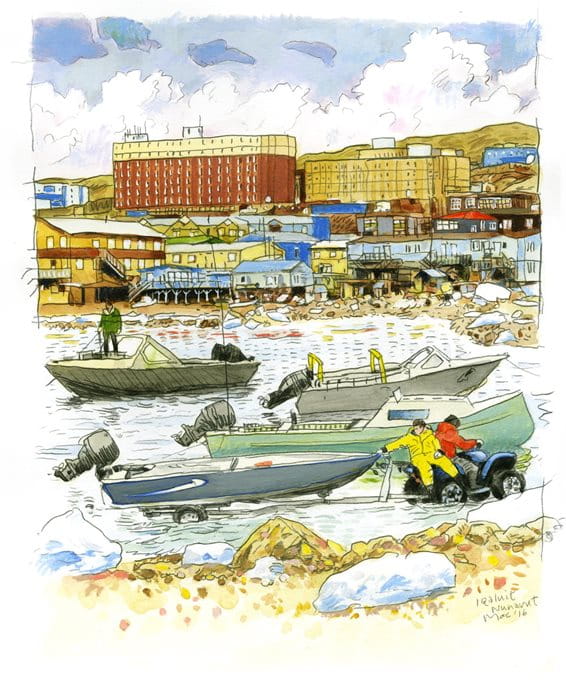

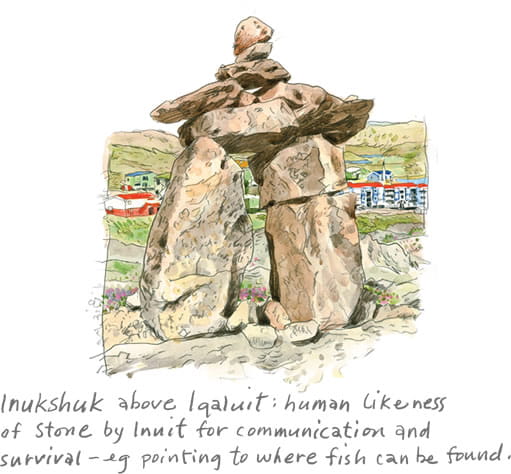

That is how “Iqaluit” translates into English from the Inuit language. It’s the name of Canada’s smallest territorial capital, just 8,000 people on the chilly shores of Frobisher Bay, a town governing a polar archipelago half the size of Western Europe that is Canada’s largest—and newest—province, Nunavut. Once a frontier for fishing and hunting, later for whaling and the fur trade, Iqaluit today is a fast-growing outpost on the world economic stage.

There is no road to Iqaluit. You fly in or, in the summer for a few weeks, you can arrive by boat. It’s a city of 8,000 people at the western point of Frobisher Bay, on Baffin Island, just below the Arctic Circle. Its name means “Place of Many Fish” in the Inuktitut language. Its history is one of travelers and centuries of nomads of the water, land and ice. Seventeen years ago Iqaluit became the capital of Canada’s farthest northeast territory, Nunavut. It was around then that it began attracting more people from the Canadian South and even around the world.

In oral history, the Inuit he met during his stay, and who still make up most of the population, descended from the Thule culture that had come from Asia. Traveling by boat and dog sled, they spread across the North American Arctic as far east as Greenland between 1000 and 1600 ce.

In the 18th century, as elsewhere in the Americas, the Inuit were decimated by diseases that came from European contact.

For the next 300 years, the Inuit who survived trapped and hunted, trading furs, meat, clothing and labor for metal knives, harpoons, pots, guns, ammunition, flour and tea with the Hudson Bay posts and whalers. When the ice broke up each year, a ship arrived with supplies and left with furs.

People are coming to Iqaluit today from all over the world, mostly for jobs in education, medicine, construction, mining and more. It even has a website promoting tourism. Sixty percent of the residents are Inuit and most others are white. Recently people from different parts of Asia and North Africa have been arriving. Being born in the South (New Brunswick) myself, I was curious about what life is like in this northern frontier of globalization.

Mayor of Iqaluit

As a mayor, you don’t have as much power as people perceive. You work with other councilors, staff and other levels of government. Iqaluit has grown tremendously since 1999. We were just over 3,000, and now we’re approximately 8,000. That puts a lot of pressure on us to manage and keep up with the growth. We have to develop new areas of land for development, laying roads and pipes, which is very expensive. To give you an idea, a kilometer of road, unpaved, is C$750,000–1,250,000. Laying pipes is another million dollars per kilometer, and to pave the road is another million.

Even though we have had five women mayors, a woman member of Parliament and a woman premier, politics here is seen as a male-dominated arena. Inuit society is divided very much on gender.

So it takes a woman with fortitude and conviction. I chose not to re-run for mayor when I was getting my first grandchild. I was glad to be able to help my daughter. Health issues are huge in Nunavut. That’s why our territorial government spends a quarter of its C$1.6 billion budget on health. My background is law, so I try to highlight and bring some rational thinking to the situation. Being a mayor is a position of influence. It’s all I can do. Sometimes I succeed.

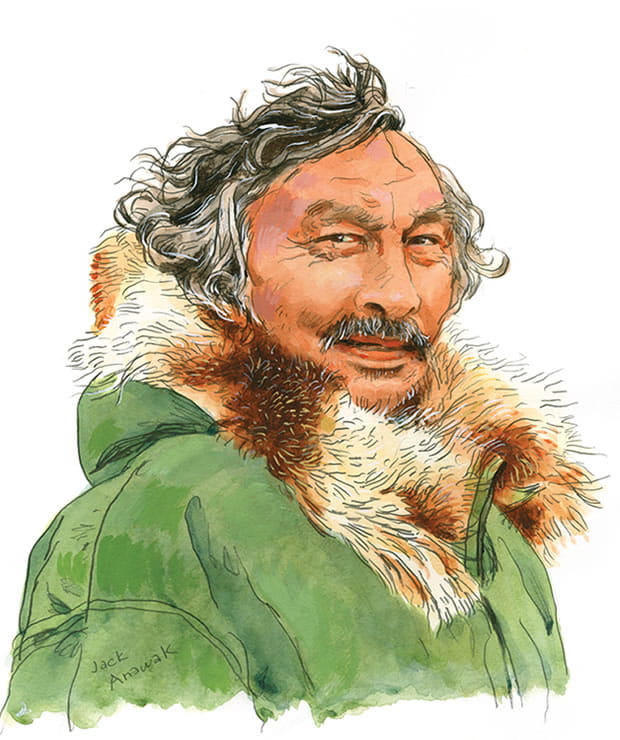

Former Member of Parliament

At the same time, I read any book I got my hands on—romance novels or the history of World War ii, didn’t matter. I was learning. None of my kids have lived in an igloo or a sod hut.

In 1975 we were introduced to our form of government. Our first local government was called a settlement council, which had no power. I was at that time mayor in Rankin. In 1988 I got a chance to run for Parliament and won a seat.

When Jean Chrétien was prime minister of Canada, we had a G7 conference in June 1995 in Halifax. The pm was a friend of Helmut Kohl, the German chancellor. He brought Kohl north after the meeting. There was a polar bear skin spread out to dry. It was the time the eu was planning to ban the fur trade the following year. “Jack,” he said, “I want you to talk to Kohl about you growing up in the North wearing fur. There’s an interpreter.” Jean claims I got Kohl to delay the ban on fur for at least another year. That gave the hunters a bit more time to plan ahead.

Executive Director, Inuit Heritage Trust, Inc.

My grandfather Abraham told me this story about when he went to the Hudson Bay trading post. If anyone wanted a rifle, he said, they stacked the Arctic fox furs flat on the floor until the stack was as high as the length of the rifle.

Inuit then were nomadic and had seasonal areas. That was our life back then. In the ’50s and ’60s, they were forced to locate in settlements, usually where there was a trading post and a Roman Catholic church. That’s where they decided to build the community. My father came from Scotland and became a Hudson Bay boy, met and married my mother in 1969.

The settlements gave the government more control of the North to prove it was part of Canada. I was born in a hospital in ’73, but my uncle was born seven years earlier out on the land, no nurses or doctors. The change happened very quick. It’s been 50 years. That’s all. Some parents never went to school, or not like the kids do now. We are slowly improving. More Inuit are going to university. We need to take on leading roles and higher positions.

Syllabics is the writing system introduced to the Inuit by the missionaries. The Cree Indians also use it. Today we are losing this in the younger generation. English is everywhere, on tv, radio, Internet, but there is an app from iTunes for Syllabics.

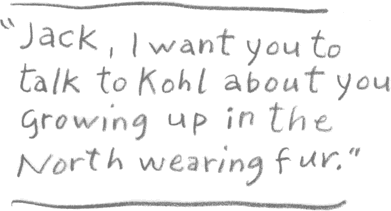

Chief Boiler and Gas Inspector, Nunavut

There’s multiculturalism in this country. Half here in Iqaluit are Inuit. Most workers have come from down south, and we work together. No problems have I seen. We are now more than 100 Muslims in Iqaluit among Jews, Christians, Hindus and so many other cultures.

I’m happy here. I like my work and the people I work with. I’m a government employee. I inspect gas and boilers in all of the 25 communities all over Nunavut. There is also an electrical inspector and also building and fire-marshal inspectors. All in our safety division. If anything is not working properly, I report it and it’s taken care of.

I was born in Pakistan, Karachi. My schooling was the British system. I’m a mechanical engineer. That’s also what I did in the military for 20 years. Once I received my immigration papers, I came right here. Most of my family were already here, in the South or in Michigan in the us.

I knew nothing about Nunavut. Writing the citizenship exam, I had to find out where it was. When the plane landed, it was dark outside. I stepped out of the plane and thought, “Oh my God!” It was winter. My inspector showed me around Iqaluit. When I went to my apartment, the depressing thing was it was light for only a few hours a day, and the temperature was in the minus-50s. There was nothing but white snow and ice. I was homesick.

When I go south I stock up on food. There is no halal meat up here. So when my provisions get low, I go south for more, and of course the family gets together as best we can. I am on the board of some committees, so I can travel south three or four times a year to meetings and conferences.

Walrus and seal are not halal because they are not fully sea animals. Fish is halal because it is always in the water. Prawns and lobster are good. In Islam there are different sects, Sunni and Shi’a. Each has its own rules for halal. Some say if a fish has scales, don’t eat it. We should all be on the same footing, but each has its idiosyncrasies.

Our plan is to set up a food bank to help serve the community. We have to nominate someone at the mosque, and our organization down south in Toronto will help out with the food storage. We need freezers and space for the other foods like cans, etc. They are waiting for us to give the go-ahead, but we have to get things here in order first. They will pay the salary for the person we hire.

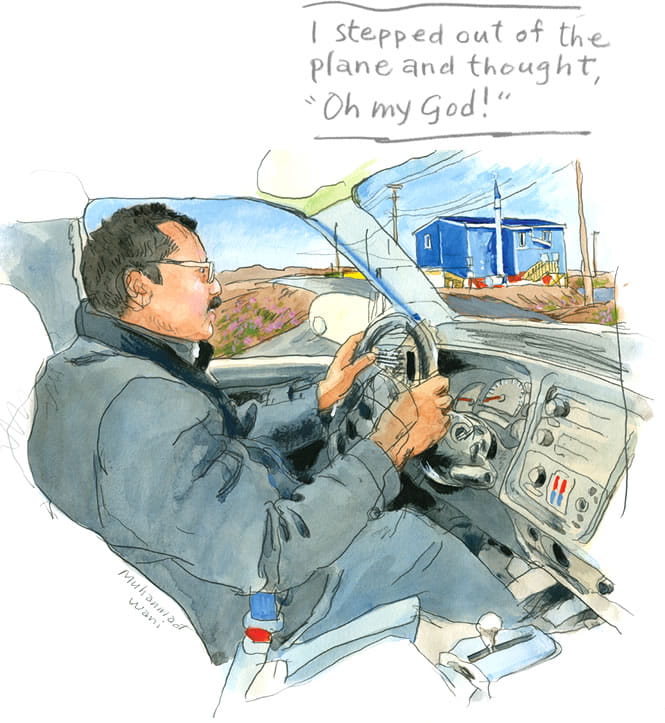

City Councilor and Editor of Nunavut News/North

I worked for a newspaper in Newfoundland after graduating from university in Fredericton, New Brunswick. I then traveled across Canada for three years before moving back to Corner Brook, Newfoundland. Tired of the gypsy lifestyle, I started to work for the Western Star there. That was in the ’90s. When I saw in that newspaper an ad for the Northern News Service, I was hit by the lure of the North. When Nunavut became a territory in 1999, they wanted someone to open the Nunavut North office.

With the increase in population, there seems to be a lot of people from Newfoundland and Quebec. Newfoundlanders are transient people anyhow. The fishing industry deteriorated so you couldn’t buy a job there in the ’90s. The 2000s had the offshore oil boom. So I took the big adventure.

Because of jobs, Iqaluit is becoming really multicultural. Workers come from as far away as Pakistan and Africa. Before it was local Inuit people. Now it’s global and some have been here longer than I. The fear here is that the language and culture may die, especially in Iqaluit.

The truth-and-reconciliation council considered the residential schools for native children as cultural genocide. Treaties have been signed, and we Canadians have not been honoring these treaties. After 17 years I still feel the distrust.

Chef and Student

I was working at Research in Motion, Blackberry, for five years at their factory in Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario. Then I went to Norway for two years, and when I got back, the job I was told that would be there wasn’t. Two weeks before I got back, they laid off 600 people from the two departments I worked in.

My wife saw there was a full-time job available at Arctic College, up there on the hill. She applied, and they got back to her real fast and offered her the job. “Holy cow, I think we are moving to Iqaluit.”

Two days after we arrived, just after New Year’s, there was the worst storm in decades, with 125-kilometer winds, and we couldn’t see anything in the dark. The whole building was shaking. We thought, “What have we done?” The temperature was down in the minus-60s. They close the schools at minus-52. After nine instructional days, they lowered the temperature limit down further to reopen the classrooms.

My wife teaches nursing. Nursing and teaching are the two programs that are available for a four-year degree at the college. My wife had a one-year contract at the nursing college. I took a job cooking at the Gallery restaurant because it would be easy walking away if we decided to leave.

But we liked it, and she took another contract. At this point I thought I should be doing more than cooking. I took a look at the teaching program. It wasn’t terribly expensive. I don’t teach yet. I’m going to do my last year.

The winter is dark, the wind howls, snow blows with crazy noises echoing around buildings. At least three times a week there are the spectacular aurora borealis, at times covering the whole sky with huge shivering green sheets. This is a nice town. People enjoy sitting and talking to each other. This place is full of oral history.

Singer/Songwriter

We don’t have a word for art. We had our community jokers, singers, shamans, healers. Most mothers throat sing to their children. My mother did. Very rhythmic really, very poly-rhythmic.

I started by going to the theater for indigenous people in Toronto. You had to audition (on tape), send it in, explain why you need to be accepted. For me it was overwhelming. I liked acting very much, but I was not prepared to make the move south so I came back north.

It was through the Native Women’s Association of Canada that I was asked if I would perform. With full band, it was new and felt good. I sang my own music.

First song I recorded was “My Mother’s Name.” It was about a dark time in Canadian history, in the ’40s, when Inuit names were replaced with numbers. I toured with my band. What? 20 years. It was never permanent. The first album was about my origins, the community and things around me. The second album was about relationships.

I wrote a song called “Lovely Irene,” and it’s on YouTube. Later I called it “Angel Street,” and it was about an abusive relationship. It was brought to the attention of the mayor of Iqaluit at the time, Elisapee Sheutiapik, whose sister was murdered. She renamed the street the town’s woman’s shelter was on Angel Street. Then she put out a plea to all mayors of capital cities to name a street in their city Angel Street in support of women. I’m not sure how many there are now. There was St. John’s, Edmonton, Regina, Fredericton, Yellowknife, Kamloops and now more. It makes me pretty proud of Elisapee.

Sometime after my last album, I lost the desire to create. It will come back I know. All I know is I’m a woman of the North. In my heart, I am where I want to be.

Documentary Filmmaker

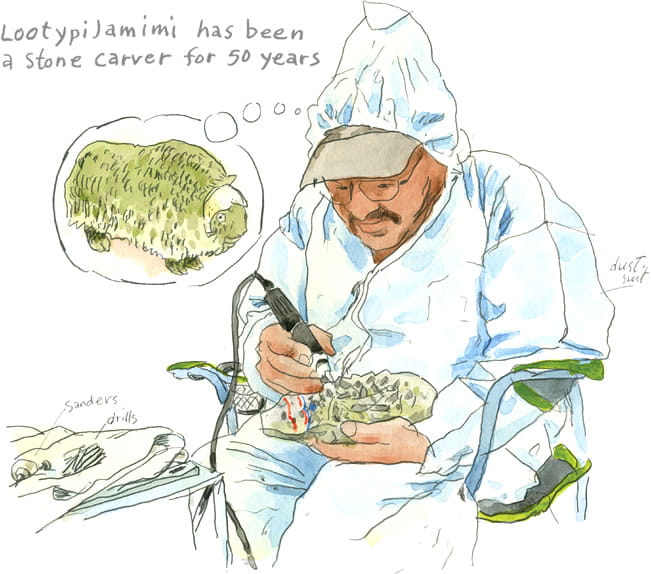

The arts and cultural industries are doing well now. Inuits have the largest number making a living at their arts and crafts per capita in North America. We have a lot of visual artists, printmakers and soapstone carvers. The film industry is relatively small, but it’s surprising the production we do. Tourism is heavily promoted but difficult to do in ways that don’t interrupt communities and wildlife.

One of my passions is advocating for the revival of the seal hunt because it’s one of the few options we have for a cash income that doesn’t simultaneously destroy the land and the animals. The seal is the biggest untapped resource we have. They are plentiful, and we eat them anyway. My documentary Angry Inuit is about how we’ve been affected. It just premiered at Hot Docs in Toronto.

Professor of Biology, University of Moncton, New Brunswick

When you have a temperature change of up to two degrees, you can have a fivefold change in predator factor. Imagine a bird nesting in Northern Quebec or as far north as Ellesmere Island. The number of predators is not the same, so a bird is very keen to travel as far north as it can to escape the predation factor. It can happen very fast.

Another direct effect of climate change is the increasing presence of humans in the north. The Mary River iron mine wants to ship iron ore south using boats all year round. To do this they have to break the ice, and that eliminates the bridge for many migrating species. Yet Nunavut needs employment and industry.

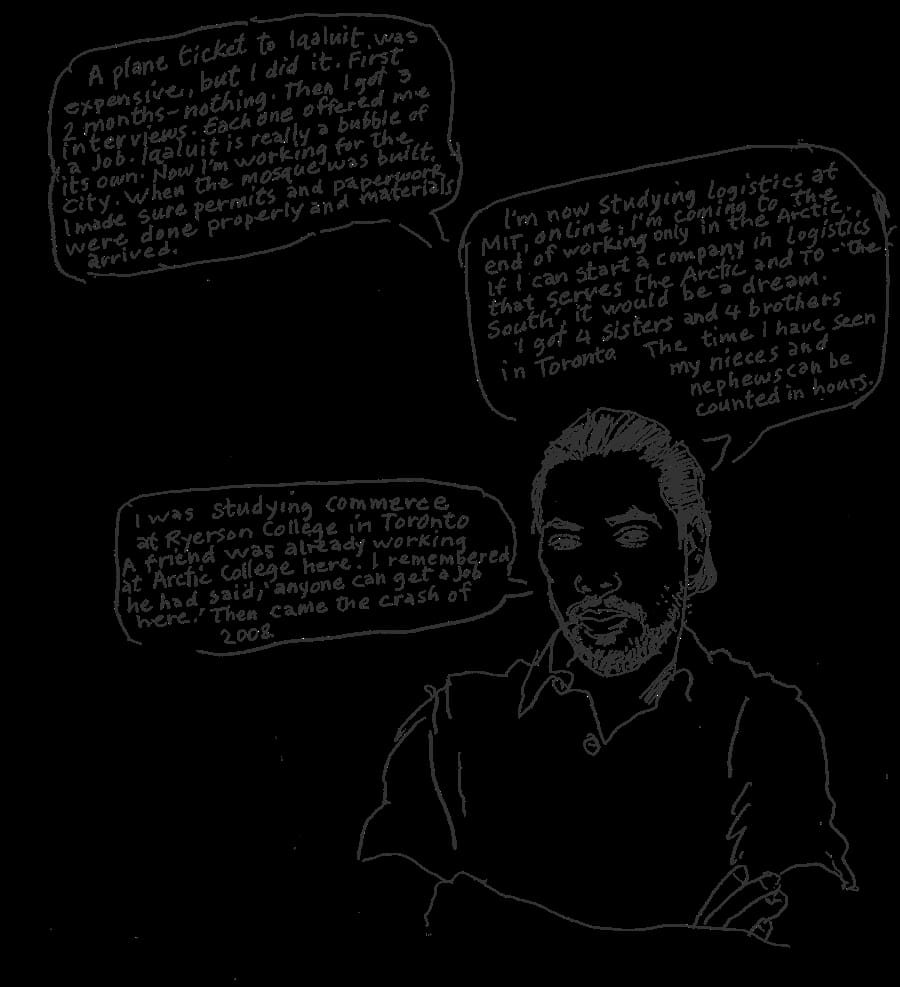

Materials Coordinator, City of Iqaluit

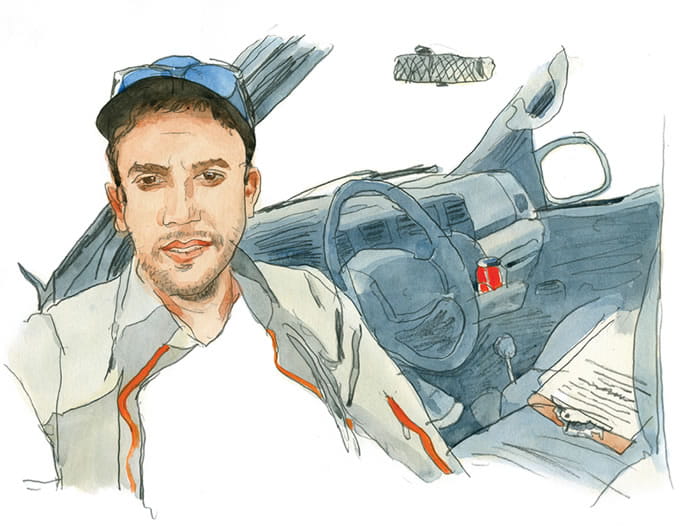

driver

I came from Morocco. I lived a half hour from the capital, Rabat. Casablanca is about two hours from my town. I met my wife online. She asked me to visit Canada, to Iqaluit. We married, and I came here in the summer of 2008. It was a big change for me, especially in the wintertime. Minus-40s to the minus-60s, colder with wind chill. I then walked to the hospital where I worked as a security guard.

Last summer when it was four or five degrees Centigrade, I left for Morocco where it was plus-54 when I arrived. Very hot for me. I couldn’t wear jeans, just shorts and a T-shirt. Most of the time was spent on the beach where there was a breeze. Now I’m used to the weather in Nunavut. Plus-10 is too hot for me.

The last blizzard we had, I was driving a school bus and dropped off workers, and then I had to pick up the kids because the school closed down and get them home. After this I bussed workers and co-workers again. When the last one got out, I drove on in the snow and got stuck in a two-meter high snow bank on the Road to Nowhere by the mosque. The road was closed, so I had to leave the vehicle there and start walking. It was late and no visibility. I was well clothed. I had on my winter parka that was made here by the help of an Inuit woman.

When I came here, I didn’t know how to drive a vehicle. No diploma. Nothing. I work with security at the hospital, then at the airport. Then I start driving a cab. I have some friends here, taxi drivers, from different countries like Libya, Tunisia, Algeria and Lebanon. 2011 until now I drive a cab. Now just part time. Night-time shifts became too much for me. We have one boy and want to spend time with him. I talked to my friend. He was manager of a construction company. He said he would teach me to drive everything.

There are some programs here in Nunavut to learn this. I pay half and the government the other half. He taught me to use all the loaders, and now after two years he taught me to drive a tractor trailer. I just got my license, Class 1, this week. Down in the South you have to go to school and spend a lot of money. Thank God I got it here.

When I came here, my wife, father-in-law and her brother took me hunting and started teaching me hunting stuff. I got a license for firearms. I bought a rifle and started hunting with family and friends. With Inuit friends I learn a lot. I bought a Ski-Doo. Driving the first time, I got frostbite. I now have a gamutik, a big box sled, to pull behind the Ski-Doo.

My son is now seven. He went out boating yesterday with his grandpa. My mom was here in March until June, when we still had some blizzards and a lot of snow blowing. We live on the second floor, and the wind shakes the house, which scared her. I told her not to worry, this is normal. She had a good time. She wants to come back again.

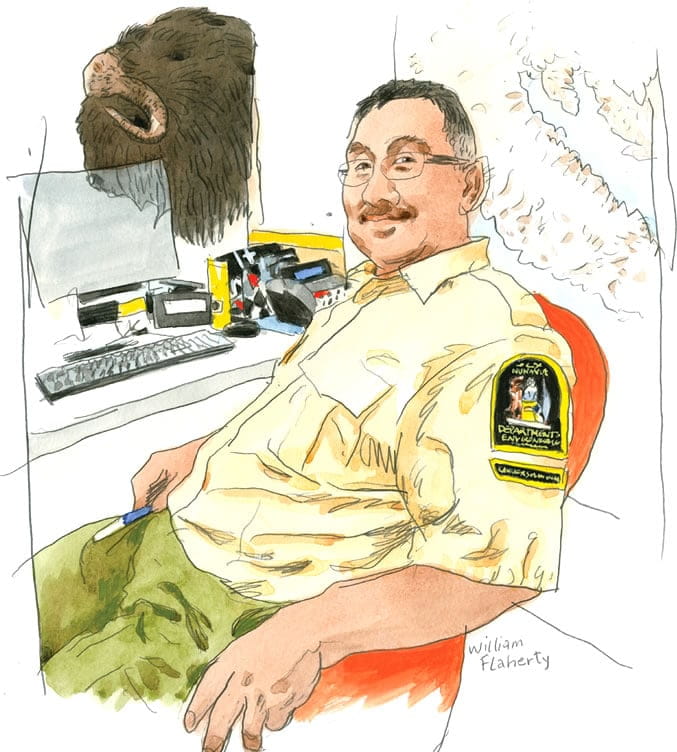

Conservation Officer, Department of the Environment

My ancestors came from Quebec, my parents and grandparents. They lived on the eastern side of Hudson Bay. I don’t have a real sense of home. It’s up there on Ellesmere Island and my home is down south also. I travel to other parts of Nunavut but mainly I stay on Baffin Island. In the winter we use snowmobiles, our only means of transportation in the snow.

When my parents were resettled, meaning sent north, they were put on the beach at Grise Fiord, and the boat left. There were no buildings. No stores. No Starbucks. No food. No shelter from storms. Just dirt and what was lying on the beach. First they had to assess their situation. What were the species available for survival? You can only hope there are caribou or seal. Don’t ask me how, but they survived. I’m one of the children.

Back in former times, your education was for survival on the land. I went out hunting for the first time when I was five years old. I was eight or nine when I got my first seal. Eleven when I helped catch my first narwhale and beluga. In regards to the polar bears, whatever you hear in the media about the Canadian Arctic, like the ice is getting smaller, that’s true, but we have many more bears right now. Healthy. A few years ago, we saw hardly any. Now we can’t stay in tents and feel safe. We have to live and vacation in cabins.

At the moment there are not many caribou on Baffin Island. This fluctuates. The musk ox are multiplying rapidly.

The media tell people there is much less ice so polar bears are unable to hunt. Not true either. Polar bears are very adaptable. They can eat whatever is on the land—eggs, seaweed, berries. They can hunt in open water. Seals sleep on the surface, even on rough sea. A polar bear swims toward a seal, dives deep and comes up under the seal. They are easy pickings.

Member of Parliament

My dad was 13 years old when he moved to a town. That has a big impact on people in that short period of time. Within 60 years we transformed from a traditional nomadic lifestyle to surfing the Internet. Surviving off the land to a wage economy.

I see us as being resilient. In the North people come up to work and fall in love with the place and end up staying. We may have the coldest and harshest climate in the world, but our hospitality and friendliness is warm.

I see now we are moving back to our old culture. We have to be self-sufficient in a different environment. It is now wages and business.

Think of it as a marathon race. Then, we ran the 50-yard dash, timewise. Are we where we want to be? No. Are we getting there? Yes.

You may also be interested in...

Ramadan Nostalgia Requires Active Reconstruction

Arts

Artists demonstrate how Ramadan traditions endure through deliberate acts of memory and care.

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

From Sultan’s Kitchen to Delhi’s Streets: Ni‘matnāma Lives On

Food

A sultan’s 500-year-old cookbook still ripples across South Asia, from kitchens to street stalls to celebratory tables, preserving centuries of technique and taste.