Looking Closer: A Conversation With Food Historian Nawal Nasrallah

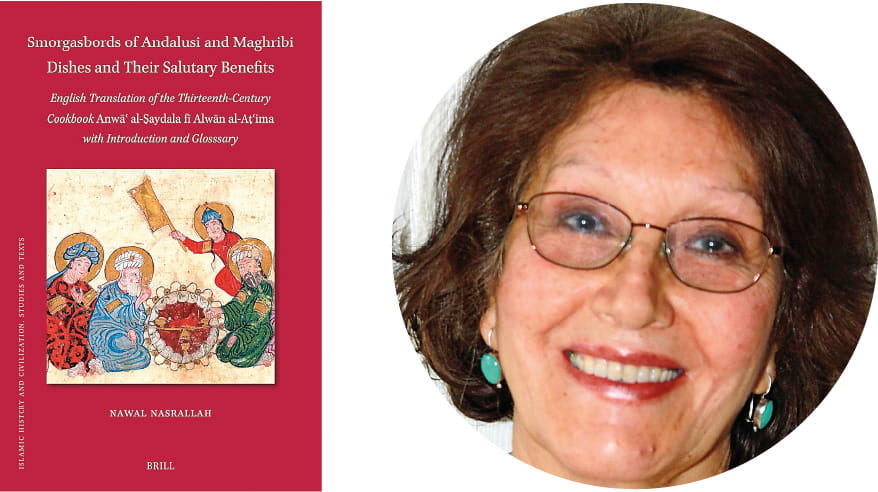

In Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, Arab food historian Nawal Nasrallah breathes new life into an anonymously compiled 13th-century cookbook.

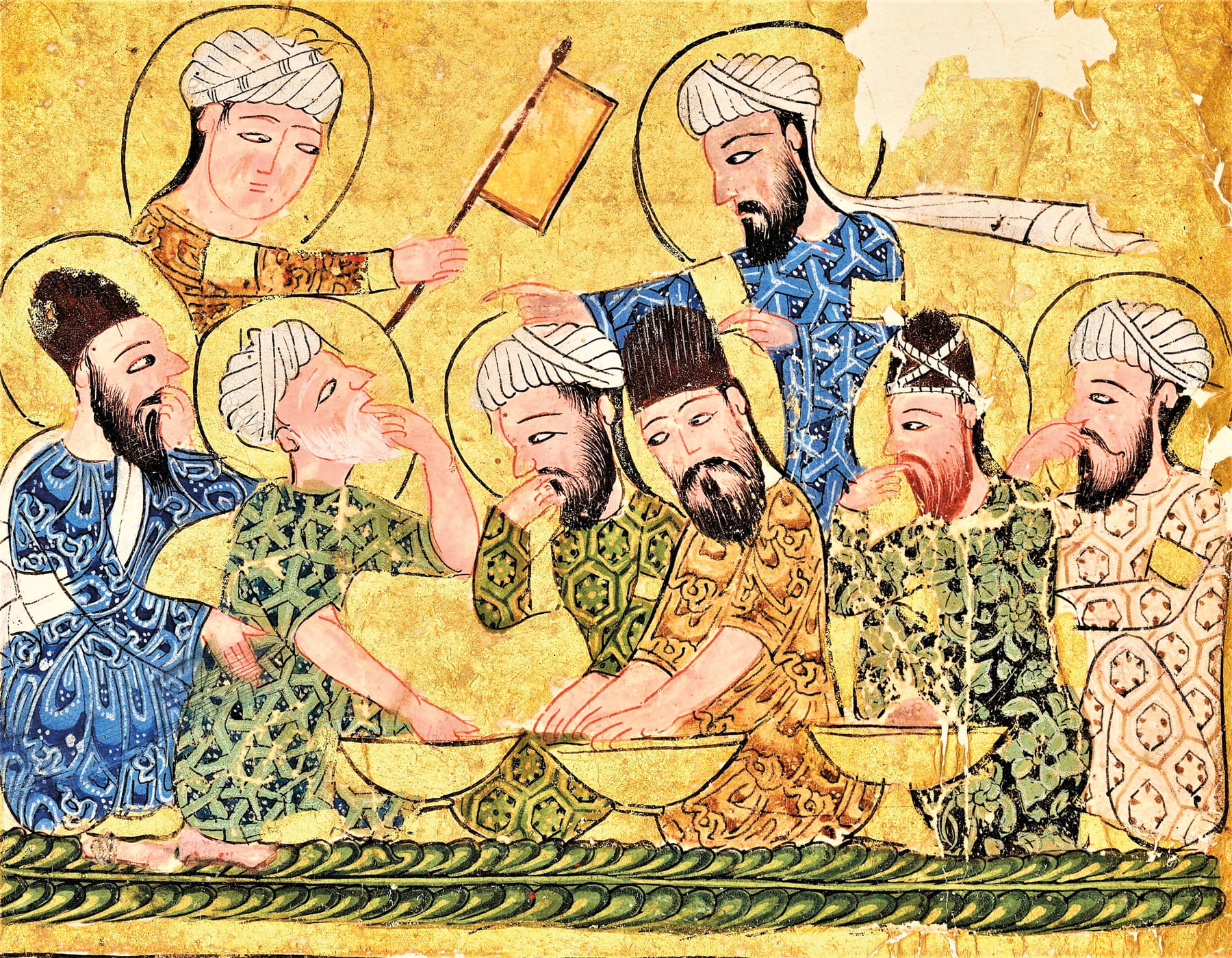

In Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, Arab food historian Nawal Nasrallah breathes new life into what was originally known as Anwa al-saydala, a chaotic, anonymously compiled cookbook from around 1220 CE.

Long dismissed by historians as amateurish, the text had puzzled scholars for decades-its tone jarring, its structure incoherent. But Nasrallah saw potential. After completing her 2021 translation of Ibn Razin alTujibi's Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes, she turned to Smorgasbords and discovered its disorder wasn't a flaw but a clue: The manuscript had been copied out of order. Its recipes, she realized, had been curated buffet style from other now lost cookbooks, likely by a compiler collecting them during bookstore visits-an accepted practice in the medieval world.

By restoring its original flow, Nasrallah reframes Anwa al-saydala not as a failed cookbook but as a rich social document from al-Andalus's cultural height. Unlike al-Tujibi's later work, which mourned a fading Islamic al-Andalus, this earlier text reveals a society still flourishing, its kitchens shaped by multiple classes and faiths. From elaborate roasts for masters to humble dishes for servants, and even edible bracelets for children, the recipes reflect a world where food crossed boundaries. They recorded daily life in a society where food bridged divides, offering rare insights into coexistence.

AramcoWorld spoke with Nasrallah about how Smorgasbords reshapes understanding of medieval al-Andalus, why inclusive cookbooks defy stereotypes and her painstaking process.

Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Maghribi Dishes and Their Salutary Benefits Nawal Nasrallah. Brill, 2025.

Where did the title, Smorgasbords, come from?

It came from the book itself, the way it is laid out when you put all the recipes in the correct order. There had been other translations of the book before mine, but they were working from a text that had recipes out of order. People had dismissed the book as chaotic.

But once I figured out how it was meant to be presented, it became clear the author was compiling the book from different cookbook texts he liked, buffet style, with lots of different kinds of dishes and different ways of making similar dishes. The book itself was organized the way you might organize a buffet. So, when I was coming up with a title, I didn't want to call it "buffet," and I thought "Smorgasbord," a Scandinavian word that is more common now.

How did you realize that the book, long dismissed as having been badly written, was actually out of order?

When other people read the book, they saw it as a writer making a mess. The language would vary, the tone and way of presenting the recipes would change throughout the text, and they assumed it was someone who just didn't know what they were doing. But I started reading it, and it occurred to me that there was another possible explanation-that in fact this was someone pulling together chunks of other books. The language was changing because he was excerpting other works. Then there was the fact that the text itself had been transcribed out of order. For me, it was about asking myself what happened to the book. Three quarters of the way through, I realized the book had been transcribed out of order. It wasn't the writer getting it wrong, it was us.

What do you think is the most probable methodology the author applied in compiling this cookbook?

He might have had the books himself, but it's more likely that he went to a bookstore and just copied the recipes he liked.

At the time, it was possible to essentially rent a bookstore from the owner. Writers would arrange to stay there overnight for a few days or a week, copying whatever they found that they liked. It could be dangerous though. A famous medieval Muslim writer reportedly died when the shelves at the bookstore he was renting collapsed on him!

How does Smorgasbords differ from your previous 13th-century cookbook from al-Andalus?

The previous book was written about 40 years later by a man in exile. There's some bitterness in his tone, and he is most focused on recording his own vanishing culture. This book, by contrast, was probably composed around 1220 CE, when Muslims still ruled most of the Iberian Peninsula in what is modern-day Spain. Because of this, the anonymous author who compiled the book is more relaxed and more expansive. He includes recipes for people from all walks of life, from roasts that will please the master of the house to dishes that a benevolent master may have the household cook prepare for the servants to give them a special meal to enjoy. There are recipes for children, including one for edible bracelets that I think is so nice, the sick, the elderly.

How does the fact that these two people were working in different places and different moments of al-Andalusi history shape each book?

The tones of the books are completely different. In Smorgasbords we have recipes from different places, from chefs, from servants, and there's a variety of dishes. Al-Tujibi [author of the later al-Andalusi cookbook] had a tone of bitterness and urgency. He was already in exile, and he wanted to preserve the cuisine that he had known and that he believed was being lost. There was no real time in his work for exploring Jewish and Christian cuisine. There was no room for anything outside of his immediate culture in his book.

Why is what we see in Smorgasbords remarkable?

You don't see this kind of inclusivity often in this period. And it conveys an idea of what life might have been like there. It offers a glimpse of a community that had a relaxed tempo, where everybody was living alongside each other. Of course, everyone is still aware of the ruling class, and social class is still very present— there are still political pressures playing out—but you can get some ideas about how the community functioned day to day.

What can people learn from reading Smorgasbords and other historical cookbooks?

In the histories and chronicles of wars and sultans and kings, you don't get any idea of how people actually lived, but you can get some ideas from these books. Smorgasbords is even more special because it doesn't focus on the great and powerful. Because of Smorgasbords we know what kind of chicken a person living in Balanssiya [modern-day Valencia] might have cooked for a Friday meal, we have a recipe for mukhallal [meat soured in vinegar], which was commonly served at weddings in Qurtuba [Cordoval and Ishbiliya [Seville). To me that's so much more interesting than what kind of cookies a certain sultan most preferred.

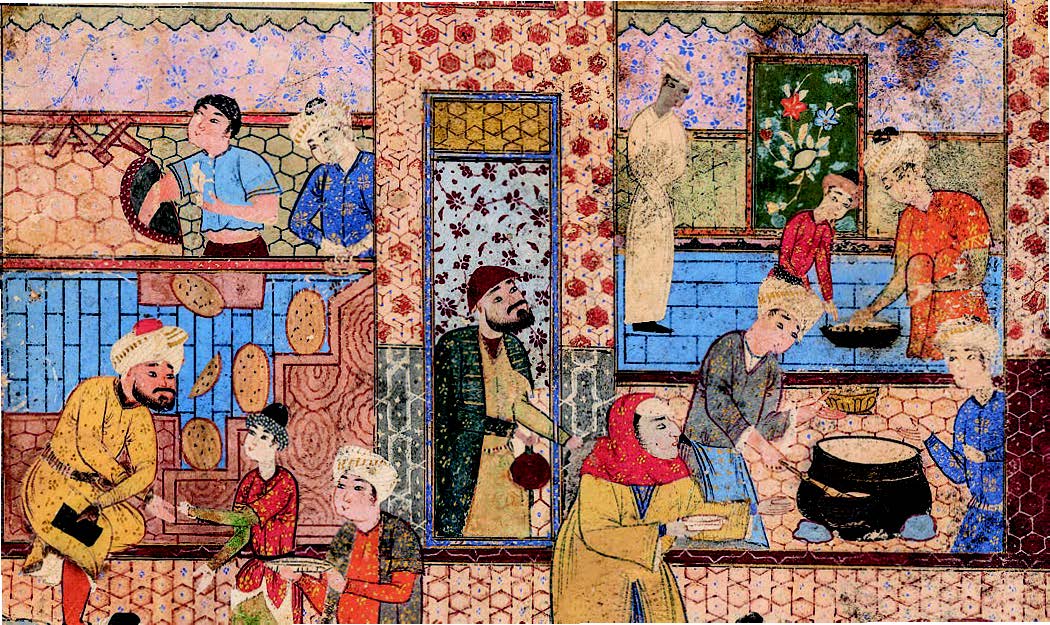

View of 16th-century fol. 11a of Jami's collection of seven poems details a busy marketplace. (BODLEIAN LIBRARIES, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD)

You may also be interested in...

Grand Egyptian Museum: Take a Tour of the New Home for Egyptian Artifacts

Arts

The Grand Egyptian Museum has officially opened its doors, revealing treasures from the ancient Egyptians and their storied past.

Ramadan Nostalgia Requires Active Reconstruction

Arts

Artists demonstrate how Ramadan traditions endure through deliberate acts of memory and care.

FirstLook: Poetic Fusion

Arts

Prior to our modern practice of image manipulation with editing software, photographers worked more with planned intention and craft.