Al Sadu Textile Tradition Weaves Stories of Culture and Identity

Across the Arabian Gulf, the traditional weaving craft records social heritage.

In the sanctuary of her bespoke workshop in Doha, Qatar, Al Anoud Al Subaie works a wooden loom with practiced hands. Strands of wool stretch across the frame, with unique patterns and shades that have colored desert life for generations. Around her rolls of woven fabric and tools sit neatly on shelves, a modern space rooted in tradition. She is making Al Sadu-an embroidery unique to the Bedouin culture of the Arabian Gulf.

For Al Subaie, a Qatari artisan, the craft has offered a profound way to reconnect with both her ancestry and inner stillness. "I was at a point in my life where I was looking for something more meaningful," she reflects. "When I found Al Sadu, it felt like it found me."

Centuries ago, Bedouin women of the Arabian Peninsula sat at ground looms, weaving more than just fabric. They were crafting the story of their people, connecting generations through wool, warp and weft. Mostly used in traditional tents and décor, Al Sadu nowadays has expanded to arts, décor and fashion and plays a significant role in preserving Gulf culture.

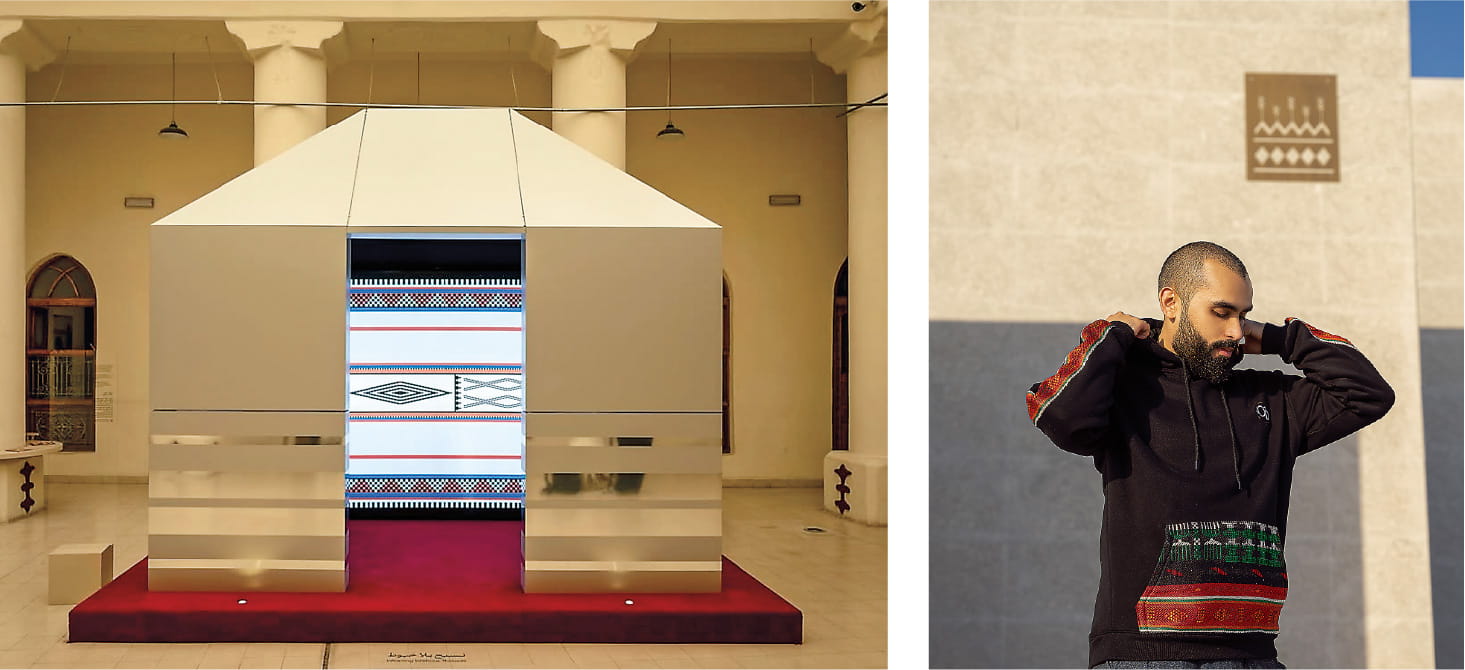

A landmark public installation by AlSadu Society integrates traditional patterns into Kuwait's urban fabric. (ALSADU SOCIETY)

Al Sadu is more than a means of textile production. It's a form of storytelling, a visual language that records identity, migration and social heritage through geometric patterns and motifs.

"My favorite Sadu pattern is 'Shajara, meaning tree in Arabic, because it allows me to weave designs alongside traditional ones by crafting different motifs each time. It allows me to be creative," explains Al Subaie.

Hailed as both functional design and cultural expression, Al Sadu offers a window into nomadic life and the enduring bond between people and the land in which they live.

Across the Arabian Gulf, efforts to revive the craft are gathering pace, in workshops, heritage centers, institutions and living rooms where grandmothers teach granddaughters.

In Qatar, the practice is more than a revival; it's a quiet act of cultural grounding.

We wanted a fabric that speaks to Bedouin culture. ... It's more than fashion; it's art, history and pride.

Sarah Hannibal works on a traditional pattern using natural dye yarns.

Foundations in the desert: understanding Al Sadu’s language

Al Sadu, which means "weaving done in a horizontal style" in Arabic, draws inspiration from the Bedouin heritage and the desert environment. The textiles, traditionally made from the wool of sheep, goats or camels, are known for their striking red, black and green arrowlike motifs and repeating bands. What sets Al Sadu apart from other weaving traditions is its use of geometric patterns as a form of visual storytelling, often reflecting the weaver's identity, environment and heritage.

"To those who understand its language," Sheikha Bibi Duaij Al-Jaber Al-Sabah of the AlSadu Society in Kuwait explains, "each design holds meaning, tribal affiliations, marital status, even invocations of protection. More than just a craft, Al Sadu is a cultural language passed down through generations."

The AlSadu Society was founded in 1979 by a group of Kuwaiti women intent on preserving Bedouin weaving traditions. Under the leadership of Sheikha Bibi, it has transformed into a nationally recognized institution, blending heritage with contemporary creativity.

Al Sadu was initially inscribed on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding in 2011 as traditional weaving of the United Arab Emirates.

In 2020, Kuwaiti AlSadu Society efforts helped secure a joint UNESCO inscription for Al Sadu weaving with Saudi Arabia. Two years later, the society deepened its commitment through a separate UNESCO nomination for the Al Sadu Educational Program: Train the Trainers, which enables teachers to pass on their weaving skills to future generations.

"Each year we hold a student exhibition to help them take pride in their work. We have in-house training workshops and courses for both children and adults for different skill needs," Sheikha Bibi says.

Woven textiles featuring regional motifs and Al Sadu-inspired patterns fill a vendor's stall at Souq Waqif Doha in Qatar. (BADER ALBALAWI)

For Sheikha Bibi, the connection to Al Sadu began in childhood, carried by her mother, one of the founding figures of the Al Sadu Project, that predates the Society.

Sheika Bibi says the group also developed the Sadu Art and Design Initiative to encourage creativity and innovation. "It's a yearly residency program that allows artists to explore contemporary themes. I love seeing Al Sadu reinterpreted through their lens and draw in a fresh new audience to experience this craft in a contemporary manner."

The Society's efforts in preserving the craft paid off, as Kuwait City's recently became designated as "World Craft City for Al-Sadu Weaving," by WorldCrafts Council.

In neighboring Saudi Arabia, where the desert landscape has shaped the lives of its people for centuries, Al Sadu has always been more than functional. "It is a visual storytelling tradition, rich in symbolism and history," says Laila Saleh Al-Bassam, an expert in Saudi Arabia's cultural heritage and textiles and a professor of the history of clothing and textiles at Princess Noura bint Abdul Rahman University.

She's spent years studying how Al Sadu's motifs are passed down through generations of Bedouin women, carrying the legacy of their people. According to Al-Bassam, Al Sadu is "a record of life in motion," capturing not just the physical environment but the "social, familial and cultural landscapes that have defined Bedouin existence."

Al-Bassam says it's not enough just to teach Al Sadu's techniques. "Whether it's making carpets, bags or wall hangings," she says, "we must keep our tradition alive, and we must learn to innovate." Al Sadu was popular with women, particularly of the desert, says Al-Bassam. "They needed a big space for the loom, for the weaving, for the dyeing. It was the life of women living in the Arabian desert, not in the cities. These women would carry their lives across the desert, so not all women in the Middle East or even the Gulf are familiar with Al Sadu. You had to be a woman of the desert."But she notes young women today are keen to learn about the threads of their past. "They want to learn about all kinds of traditional arts, weaving, beading, including Al Sadu. It's important to them and is part of their identity.

Left: Sheikha Bibi Duaij Al-Jaber Al-Sabah shows the raw materials essential to Al Sadu weaving, including handspun wool and natural fibers. She says the AlSadu Society in Kuwait is committed to preserving heritage through education. (COURTESY OF ALSADU SOCIETY) Right: A visitor peruses the Al Sadu exhibit at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, in November 2024. (WALEED DASHASH)

Al Sadu: art, décor and identity in fashion

Al-Bassam says the revival of Al Sadu ties in with the resurgence of traditional Saudi arts among the younger generation. "These arts are now being used as products for sale, particularly in tourism and hospitality sectors."

Abdulrahman A. Yousef is a co-founder of the unisex fashion label Own Design, which manufactures hoodies with Al Sadu designs in Saudi Arabia. The company's launch in 2009 was as much a statement of identity as a business decision.

"We wanted a fabric that speaks to Bedouin culture, to the tribes and to the women who traditionally wove it by hand," says Yousef. "It tells the story of how women contributed to our culture. It's more than fashion; it's art, history and pride."

And the appeal of Al Sadu is no longer limited to the Gulf. "We've got customers in Europe, America, Japan. Demand has skyrocketed. We've had to scale up production just to keep up."

For Yousef, the resurgence is deeply personal. "I see it in my own nephews; they're more connected to our heritage than ever before," he says. "Al Sadu isn't just fabric, it shows how our people adapted to the desert, turning what little they had into something beautiful, lasting and meaningful."

Wafa'a Almotawa'a demonstrates how the textiles are woven during a workshop on a nool, or a special wooden rugmaking frame, in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. (WAFA'A ALMOTAWA'A)

The craft has captured the interest of many who were not familiar with it.

For Sarah Hannibal, an American teacher in Doha, the path to Al Sadu began thousands of miles away. While studying special education in Texas, she enrolled in a weaving course — not drawn by artistic instinct but by the craft's mathematical appeal. "I can't draw stick figures," she laughs, "but weaving made sense—it's all numbers, graph paper, calculations."

Years later, married to a Qatari man and raising multicultural children, she sought to connect more deeply with their heritage.

A workshop at Doha's cultural district, Katara, introduced Hannibal to the traditional Bedouin form of Al Sadu, and there she learned the craft from the ground up. "We started with raw wool straight from the sheep. We washed it, combed it with boards full of nails, spun and dyed it over open fires. Every step was old school."

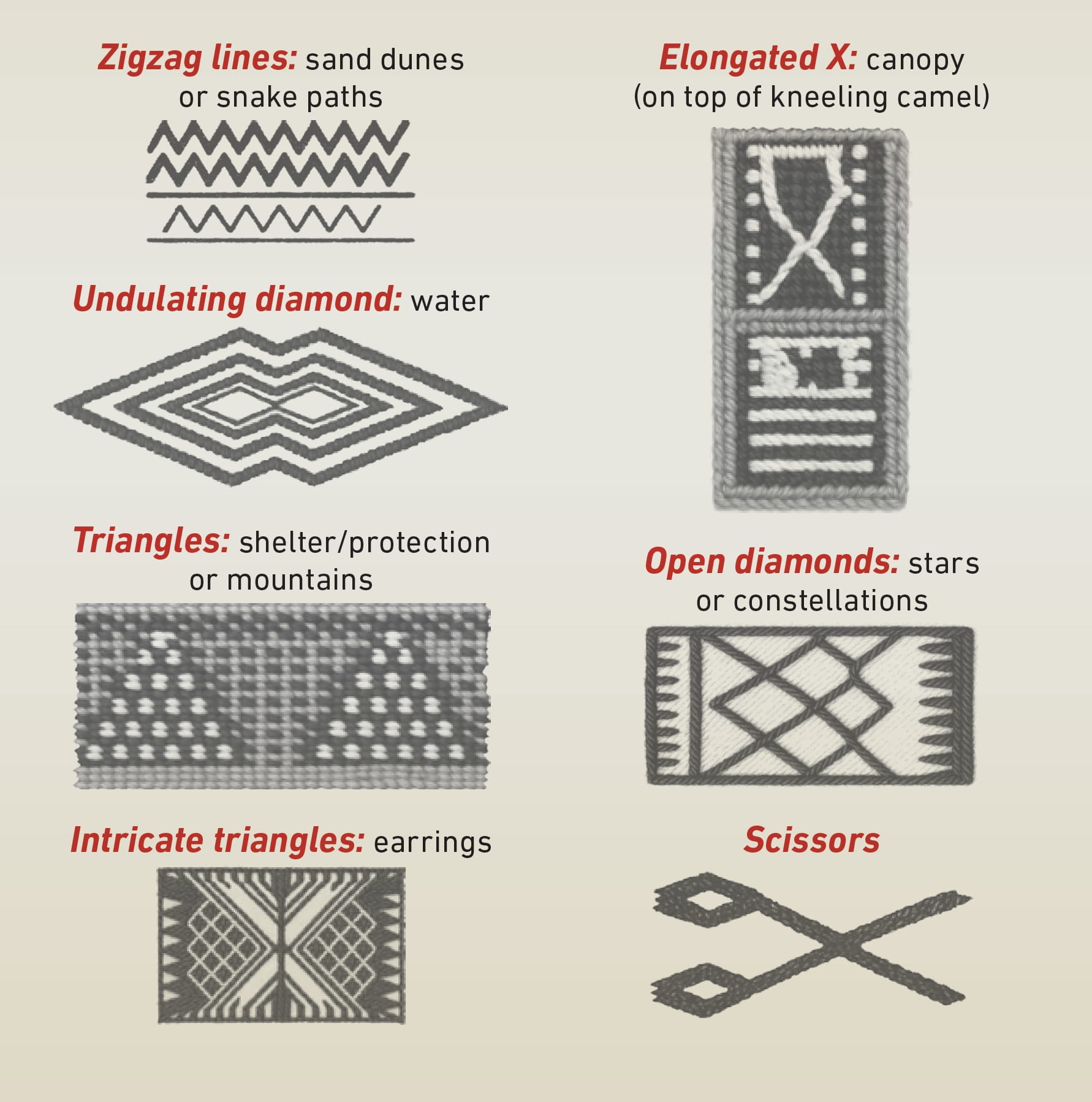

Symbols of Al Sadu

Al Sadu weaving features geometric shapes and distinctive patterns. Motifs vary across the region, but abstract and literal symbols of both desert life and manmade objects are common forms of expression. Here are some examples.

The patterns in Al Sadu represent people, places, memories.

Today, Hannibal's loom sits in the middle of her living room, a conscious nod to the communal roots of Al Sadu. "Traditionally, women worked together. They'd weave side by side, switch in when one got tired. That's why I don't tuck my loom away. My kids used to sit next to me doing their homework." She now weaves with modern tools, sharing techniques and troubleshooting in an active friends group of regional enthusiasts. "It's still handmade. Still hours of patience. But more sustainable."

Hannibal says the majority of Al Sadu weaving is what's described as warp faced, a tight fabric that is thick and sturdy. "I enjoy making functional weaving pieces. The project I currently have on my loom will be a set of kitchen towels. My favorite things to make are baby blankets and towels, but the woven fabric can be transformed into other usable items such as scarves, rugs, table runners and embellishments for abayas."

Al Subaie says Al Sadu has become a bridge between her modern life and the cultural legacy she holds dear. "The patterns in Al Sadu represent people, places, memories," she notes.

Left: "Weaving Without Threads," a contemporary digital artwork by architect Abdulmohsen Al-Oraifan, was highlighted at Sadu House's seventh Sadu Art & Design Initiative (SADI) exhibition, "Ancestral Bonds." Al-Oraifan was part of a SADI mentorship program. Right: A model wears a hoodie by the brand Own Design in Khobar, Saudi Arabia.

Now she shares her passion for the craft by teaching others and spreading its meditative benefits. "Al Sadu became my meditation, my sanctuary," she shares. "When I weave, it's just me, the threads and my thoughts. Time slows down, she says."

Both Al Subaie and Hannibal acknowledge how easily the deeper meaning of Al Sadu can be lost beneath its decorative surface. "What people don't realize," Hannibal says, "is that patterns aren't just patterns-they're identity. Tribes had their own motifs. Women wove their names, their marks, into the cloth. It's how they said, 'I was here.

You may also be interested in...

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

Arts

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.