Step Into a Visual Exchange Between Rembrandt and the Mughals

Exposure to the art and culture of India via Dutch trading ships translated to a unique phase of Rembrandt’s oeuvre. The master artist re-created 25 Mughal portraits.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606-1669), popularly known as Rembrandt, is arguably one of the greatest artists ever, famed for his myriad creations, which include biblical scenes, resplendent portraits of European elites, and a multitude of self-portraits, intense and nuanced. He was also a printmaker, draughtsman and a keen and voracious collector, acquiring from the world over.

As his career progressed over the years, Rembrandt’s collection grew noteworthy. But the distinction came with a cost. The Dutch painter spent unceasingly, compounding a financial burden that compelled him to declare bankruptcy. Consequently, the municipal authorities of Amsterdam inventoried the artist’s possessions, putting his beloved collection and his house up for sale to pay his lenders.

Among the artist’s voluminous inventory was a slim book listed as item No. 203. It contained curious drawings in miniature as well as woodcuts and engravings on copper of various garments.

The finding opened one of the intriguing chapters in the famed painter’s career, leading to a new understanding of his life and times. And nowadays we are piecing together Rembrandt’s lesser-known works.

Rembrandt’s Mughal works mark a departure from his oil-on-canvas style, such as a 1659 self-portrait, opposite, and often in size. Indian artist Bichitr’s “Jujhar Singh Bundela Kneels in Submission to Shah Jahan” (1630-’40), left, was the model for Rembrandt’s 22.5-by-17.1 cm (8.8-by-6.7-inch) drawing in pen ink and brown wash of Shah Jahan (1656-’61). (Left: ARTGEN/Alamy; Right: CMA/BOT/Alamy)

“Scholars hypothesize that this album contained Mughal artwork, the ‘miniatures’ that inspired him,” says Stephanie Schrader, curator of drawings at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California, who has explored Rembrandt’s ties to South Asia.

According to Rembrandt experts, the artist had never visited India, suggesting he had no direct exposure to Indian culture. Yet he came up with his own versions of Mughal portraits, 25 in all, depicting emperors and courtiers.

Nearly 100 years later, these Mughal portraits, drawn between 1656-1661, came to light when British artist Jonathan Richardson the Elder’s collection was auctioned in 1747.

The album was marked as “A book of Indian Drawings by Rembrandt, 25 in number” and tells the story of the artist’s Mughal connection.

“After making pen-and-ink drawings after the Mughal paintings, Rembrandt does turn to a flat, motionless language with subtle color; these qualities are found in later paintings.”

Above: Rembrandt produced this 9.4-by-8.6-cm (3.7-by-9.4-inch) version of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan and one of his sons (1656-1658) in ink on Japanese paper with a light-brown wash. (Rijksmuseum)

Indian Art in the Netherlands

What was marked as No. 203 in the inventory was just one of a variety of objects originating from China, Japan, Türkiye and India, which was then ruled by the powerful Mughals. Indian acquisitions consisted of cups, baskets, fans, garments for men and women, boxes and some 60 hand weapons.

But how did they land at Rembrandt’s doorstep?

The short answer: via the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Nederlandsche Geoctroyeerde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC)’s trading ships that sailed from Surat, a port city in west India.

“He also collected many objects from foreign countries that came into Amsterdam on VOC ships,” Schrader says, “so his interest in Indian culture wasn’t unusual.”

The Dutch East India Company arrived in India in 1602, looking out for cotton textiles produced in the southern and western coastal areas of Coromandel and Gujarat. The initial plan was to source textiles to exchange for spices like pepper, nutmeg, mace and other goods in Southeast Asia. However, in the following years Dutch trade expanded unexpectedly, leading to an enormous intra-Asian network, with Indian commodities like raw silk, muslin and opium taking center stage.

Left: “Shah Jahan With His Son Dara Shikoh,” 47.8 by 34.2 cm (18.8 by 13.4 inches), by Indian painter Govardhan (1630-’40). Right: A similar drawing by Rembrandt in ink, 21.3 by 17. 8 cm (8.2 by 7 inches), was displayed in a 2018 exhibition on Rembrandt’s artwork at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California. (Left: San Diego Museum of Art/Bridgeman; Right: ©J. Paul Getty Trust)

Who Was Rembrandt?

“Old Master”: label for Europe’s most prolific pre-19th-century painters

Known mostly for: portraiture and religious paintings and drawings

Time and place: lived and worked in Amsterdam, hub of European trade with Asia, Africa and the Levant

Mughal creations: Whether Rembrandt chose to make the copies or they were commissioned, living during the Dutch Golden Age would’ve brought items from the East into his orbit.

Rembrandt’s Mughal works mark a departure from his oil-on-canvas style, such as a 1659 self-portrait. (IanDagnall Computing/Alamy)

“Trade remained Dutch East India Company’s priority. They had permission from the Mughals to begin trading in Surat, Bengal, Coromandel,” notes Robert Ivermee, a Paris based historian of British and wider European colonialism in South Asia. “Textiles and raw silk bought in Bengal and the Coromandel coast were traded in Japan and Southeast Asia, as well as being taken back to Europe.”

The VOC ships didn’t just carry silk, cotton, spices and opium but also artworks in great numbers. By the early 17th century, art produced in the Mughal ateliers had begun circulating in Europe, with contemporary Dutch inventories referring to works as Mogolese (Mughal), Oostindes (East Indian) or Suratse tekeningen (Surat drawings). Whether Rembrandt owned an exclusive Mughal album is not known, but it is certain that he was inspired by these “foreign” paintings.

“Dutch East India Company was an incredibly active mercantile powerhouse from the beginning of the 17th century. Exchanges of goods, arts, objects would have been taking place regularly between the VOC and the Mughal court; thus, material goods and objects, including paintings, sketches and artistic renderings would have been arriving in the Netherlands in large quantities, and artists like Rembrandt would have seen and clearly had access to these,” explains Mehreen Chida-Razvi, a London-based art historian of Mughal South Asia and deputy curator of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art.

Chida-Razvi says Rembrandt produced “copies” or versions of Mughal paintings between 1656-61, by which point his interest had likely peaked. She adds Rembrandt “existed within a cultural milieu in which awareness of arts of Mughal South Asia, as well as other regions where Dutch EIC traded, would have easily come by.”

Among the surviving 23 of 25 creative copies by Rembrandt of Mughal paintings are portraits from 1656-’61 of rulers and courtiers such as opposite “Mughal Nobleman on Horseback,” believed to be Shah Jahan. (©The Trustees of the British Museum)

Rembrandt’s Mughal drawings

Exposure to the Mughal world translated to a unique phase of Rembrandt’s artistic creations.

In Schrader’s opinion, “Rembrandt was interested in the Mughal paintings as portraits as he was a portrait painter. Mughals were popular figures in Dutch culture, and Shah Jahan was Rembrandt’s contemporary—the Mughals were wealthy and powerful, much more powerful and sophisticated than the Dutch merchants.”

As for the Dutch merchants, this was about a fascination for exotica, an advertisement of sorts that hinted at their power and global outreach.

“In his earliest works, there is an interest in the exotic as markers of another time, geography and culture,” notes scholar and Rembrandt specialist Amy Golahny. “Familiarity with foreign costumes and customs would have been essential for artists if they were to portray [foreign] subjects.”

“Mughal Nobleman on Horseback,” believed to be Shah Jahan, and right Emperor Jahangir receiving an officer bearing a document, pen and ink with brown and gray wash on Asian paper, 21 by 18.4 cm (8.2 by 7.2 inches). (©The Trustees of the British Museum)

Rembrandt drew portraits of Mughal rulers including Jahangir, Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb and Muslim scholars. Shah Jahan seemed to stand out the most, as Rembrandt drew the ruler more than once.

The artworks that are not replicas but rather the Dutch painter’s interpretations still display his remarkable ability to imitate. The final creations reflect a shift in his oeuvre. All the drawings were made on Torinoko, an expensive Japanese art paper, sourced directly from Japan.

Experts portray this artistic departure from Rembrandt’s usual style as a way to reinvent himself.

Rembrandt himself attached an unusual importance to these Mughal paintings, evident in his exclusive use of Asian paper. Though in the 1640s he often used the paper to print his etchings, it is the Mughal portraits that survive on it today.

“There is more color in Rembrandt’s Mughal drawings than in most of his drawings, so he did imitate some of the color,” Schrader notes, adding that the Asian paper was more refined than European paper and a better vehicle for conveying vivid colors. The artist was fond of experimenting with different papers in his printmaking, so he probably kept it in his studio.

Chida-Razvi says Rembrandt typically worked on a much larger scale than the painted page. “His sketches could have been for self-training exercises as well.”

What Was The Dutch East India Company?

Also known as: United East India Company and Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC). The first publicly traded company in the world, VOC was devised using money from private investors to launch trade ventures in Asia.

Purpose: to secure commercial empire for then-Dutch Republic (today’s Netherlands) in Indian Ocean

Power: held monopoly on all Dutch trade and shipping with Asia and had the right to make treaties with Asian governments, enlist soldiers and wage war

Trade and influence: VOC transported millions of goods between Europe and Asia, including two-decade monopoly on East Asian spices. Ships also returned with exotica that previously reached Europe via Silk Route from China across Central Asia to Middle East and Mediterranean Sea. Commodities could be distributed in larger quantities through the VOC.

Sources: Brittanica, The J. Paul Getty Museum, WorldHistory.org, Aronson Antiquairs of Amsterdam

An anonymous painter depicts Surat, India, from the second half of the 17th century. For the Dutch East India Company, India was an important center for the purchase of cotton fabrics, spices, porcelain and art. (Roger Hollingsworth/Alamy)

Golahny’s interpretation throws further light on Rembrandt’s oeuvre at this point. “[The] 1650s is the decade of a varied, meticulously careful draftsmanship, as for example with the Mughal drawings. He also copied equally meticulously drawings by [Venetian artist Andrea] Mantegna. So, he is looking beyond local markers to imagery from distant lands more broadly than only the Mughal miniatures. In both the Mughal and Mantegna copies, Rembrandt is interested in the technique of the originals.”

Golhany adds that in the Mughal copies, Rembrandt has a fine pen, but his approach is to capture the pose, garment and sometimes the expression of the model without imitating the originals’ fine and closed outline. That is often filled in with opaque watercolor.

Each drawing paid particular attention to postural gait, clothing and accessories. Rembrandt interpreted Mughal styling and never missed the details of the jamas (stitched frock coats), chakdar (full-skirted frock coats, a variant of jama) mostly made of muslin, ornately designed patkas (sashes), jewelry, turbans and their specific ornaments called sarpech, and the embellished jutis (mules, or flat slide-in shoes worn by both Mughal men and women).

These were alien and culture specific to Rembrandt, yet he included them every time he drew. To highlight the smallest Mughal elements within his otherwise monochrome schemes of brown-wash and gray ink compositions, he used red and yellow chalks and washes of red chalk to color shoes, sashes, turban pins, sword hilts and the like.

He was also interested in the physiological details of his artistic subjects. He meticulously documented Mughal features including noses, beards and moustaches; in one of his Shah Jahan drawings, he produced a white beard, indicating grief after empress consort Mumtaz Mahal’s death. Schrader believes “copying was his way of learning about another style of making portraits.”

Exposure to the art and culture of India via Dutch trading ships translated to a unique phase of Rembrandt’s oeuvre. The master artist re-created 25 Mughal portraits, including the one above. (RIJKSMUSEUM)

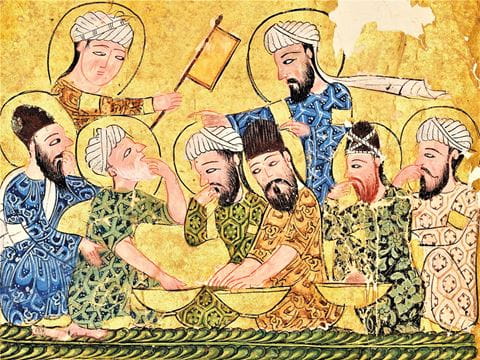

When it came to Rembrandt’s interpretation of Four Mullahs Seated Under a Tree, he prominently included new elements in his signature style. Unlike the original Four Mullahs (attributed to an unknown Indian artist, 1627-1628), in which the four wise men are seen discussing spiritual matters while referring to books on a terrace with a carpet laid out, Rembrandt’s version has no books, and the subjects are under a tree. Other minute differences appear, such as the designs of the coffee cups and background settings.

In his print Abraham Entertaining the Angels (1656), which scholars believe is again inspired by Four Mullahs, Rembrandt changes the theme, expanding beyond studying and recording a Mughal composition. He retains the overall essence of his source but details it with newer elements. For Rembrandt specialists this painting serves as undeniable evidence of his Mughal influences.

“After making pen-and-ink drawings after the Mughal paintings, Rembrandt does turn to a flat, motionless language with subtle color; these qualities are found in later paintings,” Golahny says, citing Flora (Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York), Woman With a Pink (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis (Nationalmuseum in Stockholm).

This distinct set of sketches isn’t well known to most Rembrandt admirers, experts say. “They don’t look like Rembrandt’s work—especially the late work,” Schrader says. “They are atypical and show him working in a much more refined manner than he is known for.”

But Rembrandt’s connection with the Mughal miniatures reflects his aspiration to know about a world beyond Amsterdam and Europe, which in turn unfolds a story of cross-pollination and intimate learning. His immaculate details of the physiognomies, garments and accessories are telling enough of his cosmopolitanism, thoroughly defining him as a lifelong learner, curious and open.

By drawing the rulers and vignettes of the magnificent Mughal empire, Rembrandt may have been performing an exercise in newer art techniques. Or perhaps he instead was signaling a deep interest in a foreign culture and a sophisticated world.

You may also be interested in...

Meet Sculptor Marie Khouri, Who Turns Arabic Calligraphy Into 3D Art

Arts

Vancouver-based artist Marie Khouri turns Arabic calligraphy into a 3D examination of love in Baheb, on view at the Arab World Institute in Paris.

Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, a Conversation With Food Historian and Author Nawal Nasrallah

Arts

In Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, Arab food historian Nawal Nasrallah breathes new life into an anonymously compiled 13th-century cookbook.

Grand Egyptian Museum: Take a Tour of the New Home for Egyptian Artifacts

Arts

The Grand Egyptian Museum has officially opened its doors, revealing treasures from the ancient Egyptians and their storied past.