Mundane to Magnificent: Yale Manuscript Exhibition Illuminates Muslim Knowledge

Manuscript exhibition reveals handwritten treasures spanning centuries and nations, in graying script and glorious technicolor, on ancient papyrus and gold-coated paper.

I walk toward the square, modernist building through cold, driving rain. A stark block crafted from marble, granite and bronze, Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library hulks among the institution’s neo-classical, Greek- and Roman-inspired structures. To some, this building exemplifies the best of modern architecture. To me, its sightless marble windows make it a perfectly symmetrical gray honeycomb with none of the sweetness.

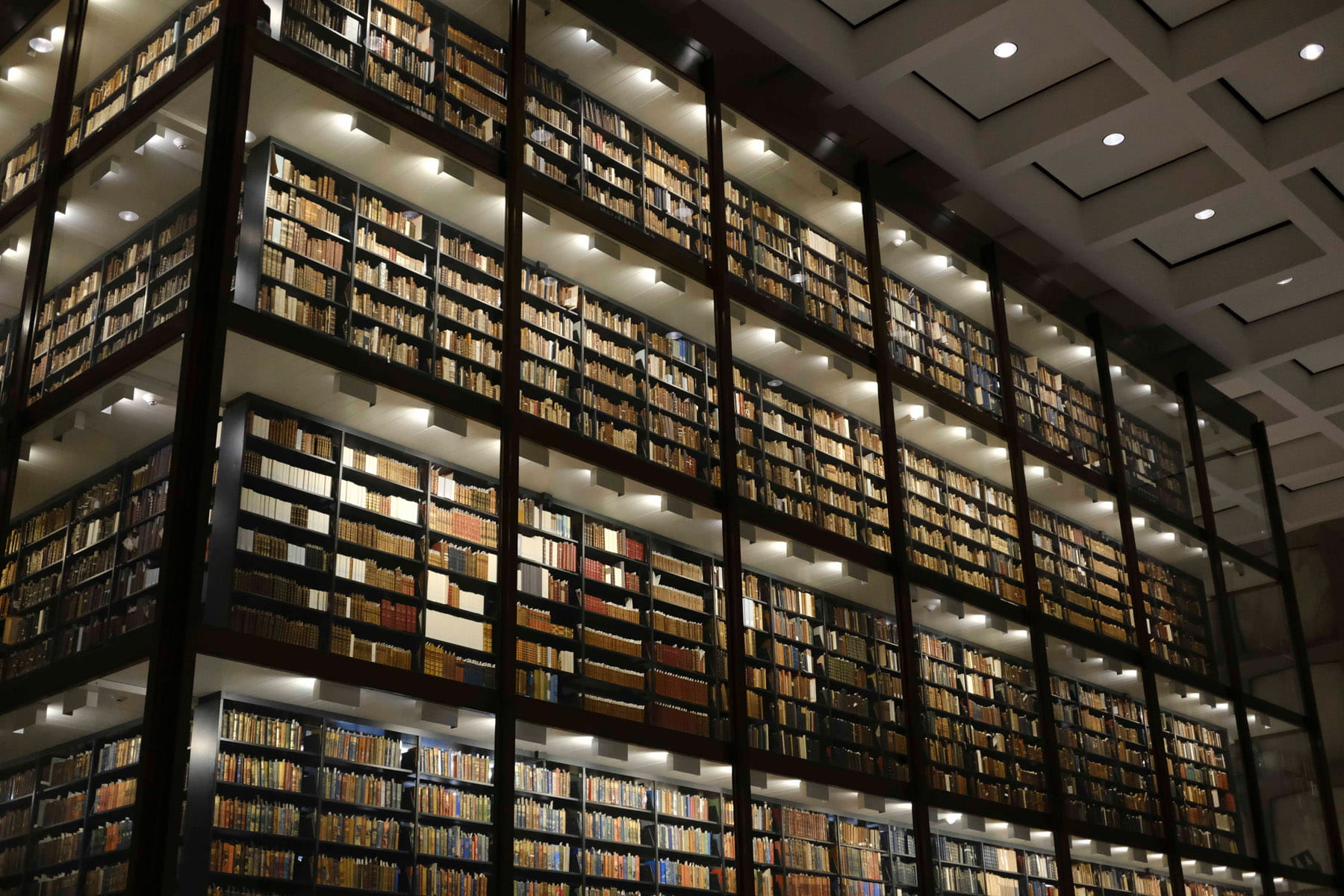

But stepping through the doors, I am momentarily dumbstruck by the golden incandescence waiting on the inside: Six stories of glass-encased rare manuscripts soar upward, bathed in gentle yellow light that warms the leather covers of ancient books, setting their tooled covers and gilded lettering aglow.

A large, freestanding three-paneled case announces the name of the exhibition: “Taught by the Pen: The World of Islamic Manuscripts.” It includes the full text of Surah 96, the Qur’anic passage from which the title is taken. According to one of the curators, Agnieszka Rec, the surah is also carved above the front doors of Yale’s central Sterling Memorial Library and was chosen because it speaks to how Muslim scholars “extended almost every field of knowledge in astonishing new ways.”

“Taught by the Pen” is the largest public display of Islamic manuscripts to date. (© Photo by Mara Lavitt Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.)

Beinecke Library’s Muslim Manuscripts

If the Beinecke itself is a safe and the antiquarian tomes inside are the jewels, the exhibition I have come to see—"Taught by the Pen”—is an elaborate necklace encircling the graceful neck of the glowing glass enclosure. In each of the cases that surround the column of rare books lies a curated collection of one-of-a-kind, written artifacts of Islamic culture, each one a perfect jewel.

I have been drawn to the exhibit for its promise of a glimpse of some of the rarely seen and unusual items among the Beinecke’s 4,600 Muslim manuscripts. Most of the eclectic collection is written in Arabic, but Turkish, Latin, Hebrew and Persian are also represented.

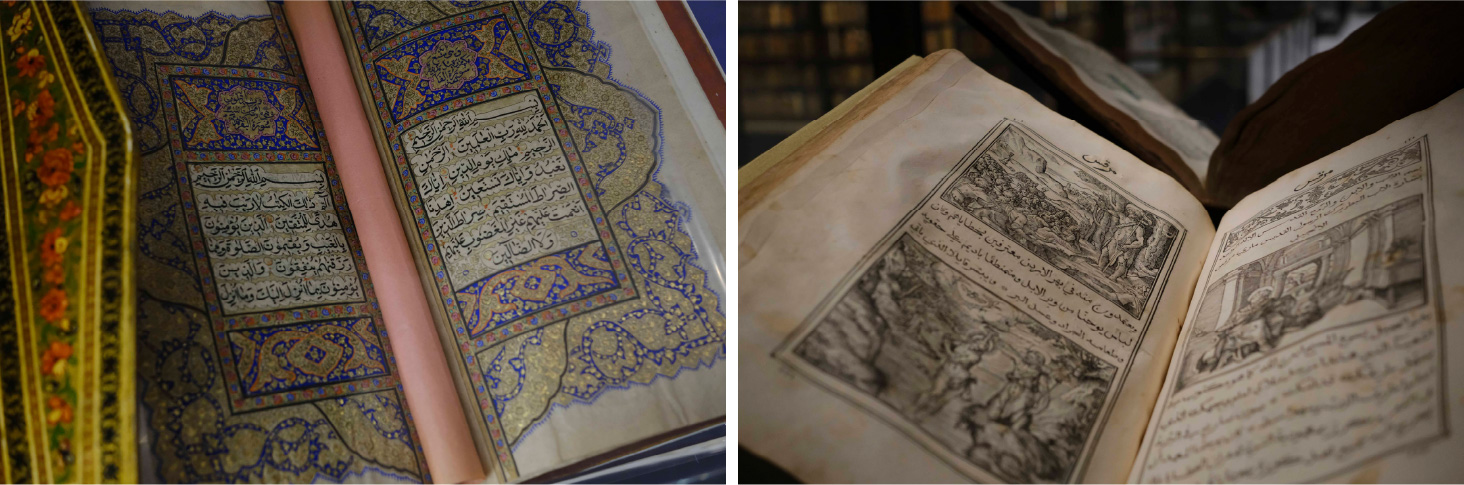

The collection is, indeed, stunning in the diversity and beauty of the objects—but it is the inclusion of items used by people in their everyday lives that is most moving: An astrolabe for calculating the positions of heavenly bodies proved useful for travel but also for finding qiblah (direction of prayer). The 1860 deck of As Nas cards, a popular game in Persian households during the 18th and 19th centuries, remains vibrant. An 1835 travel permit written in Ottoman Turkish was granted to an American man, his wife and their translator as they journeyed across the empire.

Exhibition visitors are greeted by six stories of glass-encased rare manuscripts. (J.P. Vellotti)

An anonymously written 17th -century “conk,” or personal notebook, features silver-painted pages with bits of folklore and poetry while other volumes include elaborate doodles, like the Turkish warships in a 16th- or 17th-century miscellany book. An 18th- or 19th-century amulet scroll written in Arabic with verses from two different chapters of the Qur’an was rolled into a silver and gold cylinder and worn about the neck.

When it came to everyday life, I also find that some of the manuscripts carried a double meaning. For example, the berat (privilege) of Turkish Sultan Abdulhamit II, written in 1896, granted two-and-a-half measures of white flour to a Sufi master for life. The curators included it because it “reflects the administrative power of the ruler” at a time when the Turkish caliphate was the seat of spiritual leadership. But to me this simple stipend signifies that sometimes the most mundane gifts are also the most valuable.

The largest public display of Islamic manuscripts to date, “Taught by the Pen” also offers a glimpse of the rarest items, such as the 12th-century copy of Ahmad ibn Yahya al-Baladhuri’s Futuh al-Buldan, chronicling the expansion of the Islamic Empire after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 CE, along with a fragment of a ninth-century letter written in Arabic on papyrus. Through these I get an intimate look at how Muslims perceived themselves, others and the world around them from the earliest times.

In addition to Rec, who is the Beinecke Library’s curator, “Taught by the Pen” was researched and installed by Roberta L. Dougherty, Yale Library’s librarian for Middle East studies, and Özgen Felek, a lector of Ottoman in the department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations.

They tell me the exhibit’s goal is to reflect how Muslim societies worldwide understood the times and places in which they lived by including what they call “very major texts in each genre,” including science and medicine; literature and poetry; math; philosophy; history; religion; spirituality; language; geography, and more.

Left: The exhibition is remarkable for the diversity and beauty of objects, some ornate and others ordinary. Right: According to the curators, the goal is to reflect how Muslim societies worldwide understood the times and places in which they lived by including a variety of texts. (J.P. Vellotti)

“It is possible to imagine a person from hundreds or even a thousand years ago consulting and using these items.”

Islamic History on Display

Walking among the impressive assortment of manuscripts in all these areas, I am continually drawn to those items that speak to the actual lives of people across continents, social stations and professions. Inclusion of such items is not the norm for exhibitions of Islamic manuscripts, which most often focus on religious texts.

Dougherty says the group chose objects that “emphasize that such things, particularly those items created for non-elite persons, have their own beauty and purpose. It is possible to imagine a person from hundreds or even a thousand years ago consulting and using these items.”

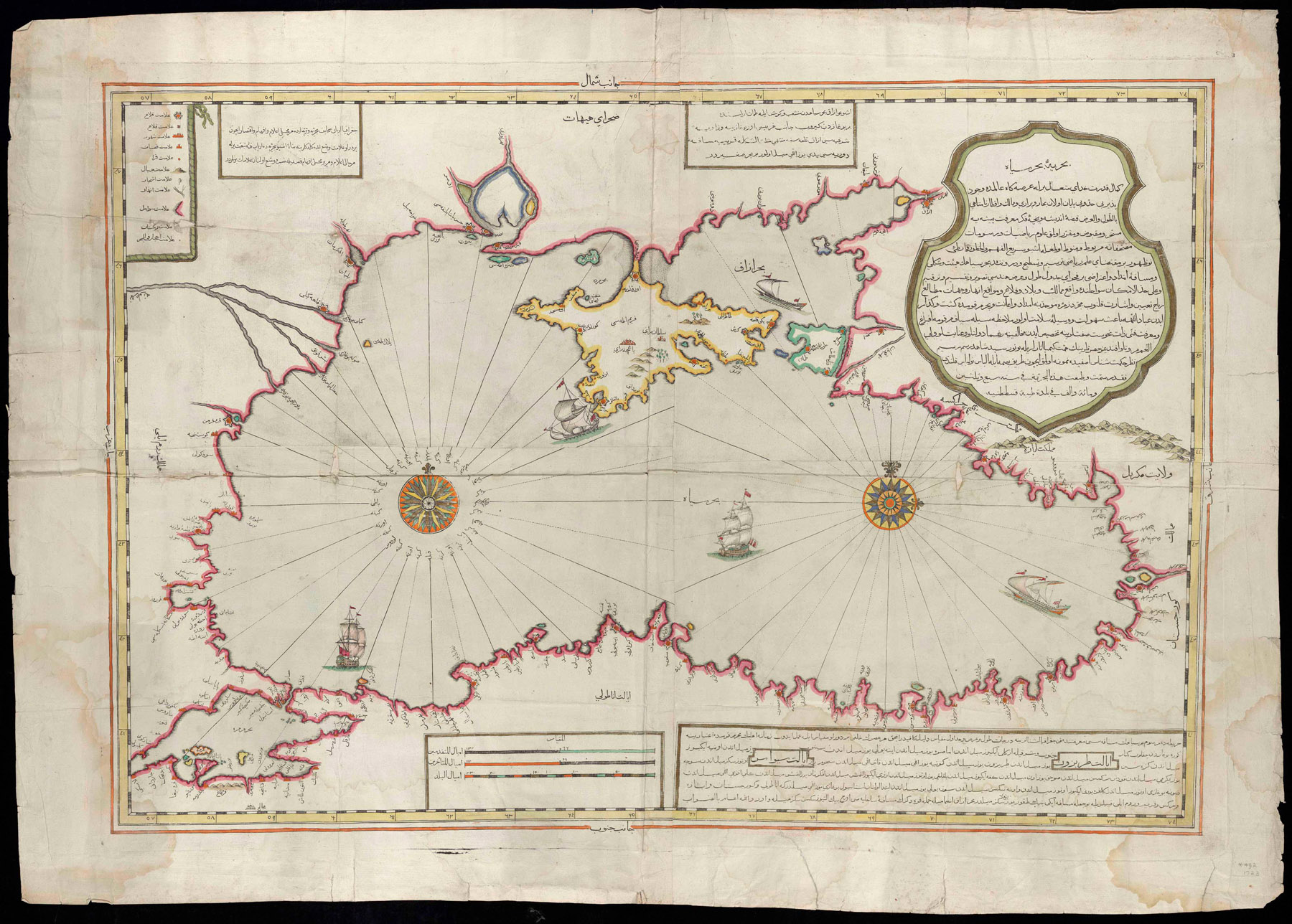

Among these are maps, like those by Unitarian-Hungarian convert to Islam Ibrahim Muteferiika (ca. 1670-1745), which show the reach of Muslim curiosity beyond the borders of the Islamic world that were also practical tools upon which a sailor surely depended. As a scholar of American and Caribbean colonial history, I am delighted by the anonymous Tarikh al-Hind al-gharbi al-musamma bi-Hadith-i naw (History of the West Indies, known as the New History). This treatise on the discovery and exploration of the New World was presented to the 16th-century Sultan Murad III and is only the fourth book printed in the Arabic alphabet in the Ottoman Empire.

Besides the written word, “Taught by the Pen” includes maps, such as this one of the Black Sea from 1724 or ’25, with text in Ottoman Turkish, by Ibrahim Muteferiika.

On the second floor, a gold-paged 19th-century alphabet primer speaks to the daily lessons of a privileged child while another gilded book—a collection of poems by the son of one of the last Crimean Khans—reveals a young man’s ambitions to literary artistry.

The exhibition’s physical layout builds anticipation: on the first floor, one of the oldest handwritten items—some on paper fragments with faded ink that belies their importance. Upstairs, I am bedazzled by illuminated manuscripts illustrating the most beloved tales of the Middle East—the love story of Layla and Majnun or the Persian Shahnameh (Book of Kings)—told aloud over and again, in the simplest to the most magnificent households, even to this day.

Yale University’s Beinecke Library houses 4,600 Muslim manuscripts. “Taught by the The World of Islamic Manuscripts” is on view at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. (© Photo by Mara Lavitt)

I find myself delighted by what I thought was a deliberate nod to the flow of Arabic script in the way some of the text panels and labels lie to the right of the objects, forcing the viewer to move left to observe them. Even though the curators later tell me this is just happenstance to assist the flow of the exhibit, it is a charming bit of luck that stays in my mind.

By the time I reach the last display case, I have long forgotten the rainy world outside. For a few hours I am immersed in Islamic cultural achievement over centuries and across nations, in graying script and glorious technicolor, on ancient papyrus and gold-coated paper. Taught by the pen, I had never dreamed of such stories that are now indelibly scribbled on my mind.

“Taught By the Pen: The World of Islamic Manuscripts” is on view through August 10, 2025, at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

You may also be interested in...

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

Restoration Uncovers Beauty of Georgia’s Hidden Wooden Mosques

Arts

Until recently few outsiders knew the wooden mosques dotting the highlands of Georgia existed, leaving many of them to deteriorate. The rediscovery of the architectural gems has sparked a movement for their preservation.

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.