Uncovering Georgia’s Unique Wooden Mosques

Until recently few outsiders knew the wooden mosques dotting the highlands of Georgia existed, leaving many of them to deteriorate. The rediscovery of the architectural gems has sparked a movement for their preservation.

A corrugated-metal minaret glinting in the late-afternoon sun is the only indication that the structure beside it is a mosque. The building, also clad in metal sheets, betrayed nothing of the centuries-old woodwork and rich decorations it sheltered.

In sharp contrast to its drab exteriors, an explosion of colors greets visitors within. Orange, blue and yellow floral arabesques blossom on the wooden pillars flanking the central qibla wall that indicates the direction to Makkah. Blue-and-gold floral reliefs frame the deep-green central prayer niche, or mihrab, with swirling medallions in striking metallic hues that highlight the adjacent minbar, or pulpit, from where the imam delivers his sermon. The caretaker points to an inscription on the minbar that dates the decorations back to the Islamic calendar year of 1344, or 1926 in the Gregorian calendar.

This is Beghleti mosque, one of dozens of richly decorated wooden mosques built between 1814 and 1926 that survive in the highlands of Adjara, a region of Georgia. They bear witness to a chapter in the country's rich and complex history as vestiges of its little-known Islamic heritage that survived decades of Soviet rule.

Metal minarets, like that of Beghleti mosque, were rebuilt post-Georgian independence to replace wooden ones destroyed by the Soviets in the 1930s.

Until recently, few outsiders knew of their existence, leaving many of these wooden shrines to deteriorate over time. Now their rediscovery has sparked a growing movement for their preservation.

Georgia, a nation nestled between Russia to the north and Türkiye to the south, is renowned for its deep-rooted Orthodox Christian heritage. However, in the Lesser Caucasus range along the Black Sea coast, Islam laid roots during three centuries of Ottoman rule that began in the late 16th century.

Starting with noblemen, the ethnic Georgian population of Adjara gradually converted from Orthodox Christianity to Islam, leading to a surge in mosques being built in villages toward the end of the 18th century, explains Ruslan Baramidze, an ethnologist at Batumi Shota Rustaveli State University who has written extensively about the history of Adjara’s Muslim communities. He notes that villagers continued to build mosques even after the Russian Empire reclaimed Adjara as a part of Georgia in 1878 and up until the Soviets took over in 1921 and restricted religious practice.

(T)hese buildings in their design and decoration are unmistakably Georgian mosques built under Ottoman influence rather than Ottoman mosques imposed on Georgian territory.

The details of the 1907 Dghvani mosque's central internal dome remain.

Aslan Abashidze, who serves as the mufti, or religious legal adviser and community leader of the Khulo municipality, recalls stories from his childhood about authorities destroying the minarets of every village mosque to stamp out religious practice, but some were spared because their modest exteriors resembled traditional houses.

"Villagers offered to turn the mosques into agricultural warehouses, and this helped save many of them,” recalls Abashidze.

Following Georgia’s independence in the 1990s, it was villagers like Abashidze who, with fellow believers, reopened some of these mosques, carrying out patchwork repairs with materials they could afford.

"We had to work with the resources we had. We get up to 4 meters [more than 13 feet] of snow in winter, and wood is very hard to protect," says Abashidze. This is how historical wooden mosques like Beghleti came to be covered in corrugated-iron sheets with metal minarets rebuilt alongside.

Today, surviving wooden mosques are slowly crumbling away while others have been replaced by concrete mosques.

Nestan Ananidze, left, who campaigns to preserve Adjara's old wooden mosques, shares a love for the architectural gems with Aslan Abashidze, the religious legal adviser and community leader of the village of Khulo.

Wooden mosques’ renewed legacy

It is only in the past decade that historians, international researchers and local activists have begun to shed light on these architectural gems, highlighting their unique blend of Ottoman influence and Georgian craftsmanship.

“(T)hese buildings in their design and decoration are unmistakably Georgian mosques built under Ottoman influence rather than Ottoman mosques imposed on Georgian territory,” writes Angela Wheeler, a Harvard University doctoral fellow and researcher in architecture, urban planning and cultural preservation, who co-authored a book on Adjara’s wooden mosques in 2018.

She says that most mosques, new and historical, are immediately recognizable by their domes, minarets, arched entrances or gates.

“So it’s quite striking to enter a completely unremarkable wooden building … only to find an interior alive with color, carvings and a decorated dome,” she says, adding that locals built Adjara’s mosques in the same style as traditional interlocking wooden cabins and that traveling artists would decorate them.

“Local masters from [former] Lazistan, from Adjara, from Artvin, from Shavsheti [present-day Şavşat in Türkiye] built and decorated these mosques using traditional methods of timber masonry common throughout the wider region,” says Baramidze, explaining that these medieval Georgian territories now lie within modern Türkiye and guilds of artisans would freely cross what are now international borders.

Masters from the Laz community, an ethnic Georgian group whose members now live primarily in Türkiye, became particularly sought after to decorate these mosques, working with local Adjaran carpenters and woodworkers.

“They [were] all Georgian masters who had the opportunity to know both the folk buildings of different parts of Georgia and the vernacular buildings of peoples living in Ottoman territory,” concurs Maia Tchitchileishvili, an art historian and professor at Batumi Art State University.

Ismail Beridze, 89, waits for Friday prayers to start at Ghorjomi, Georgia's largest wooden mosque.

A common Laz motif that also appears in the group clothing is murals of cornstalks, which adorns many wooden mosques, serving as signatures of the Laz masters who decorated them, she says.

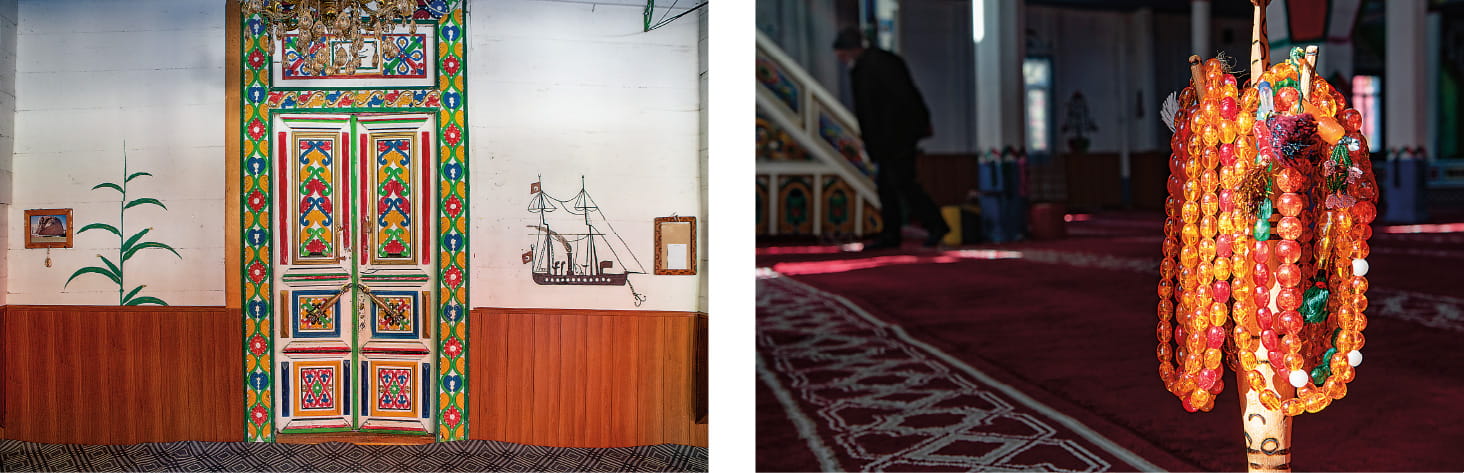

Murals of both cornstalks and Ottoman steamships prominently flank the entrance doors of the 1903 Ghorjomi village mosque, Georgia’s largest wooden mosque. Its centerpiece is five richly decorated internal wooden domes supported by 8-meter (26-foot 3-inch)-tall elm pillars.

Until then, older wooden mosques typically featured a recessed square-shaped pyramidal ceiling with alternating layers of wood, an ancient architectural style common throughout the Caucasus and Central Asia, explains Baramidze.

Older mosques also incorporated many elements of ancient Georgian motifs found in medieval stone churches like the borjgali, a radiating spiral symbolizing the sun, as well as running braids and interlocking spirals. Grape vines, frequently seen in Orthodox church iconography, also appear in engravings and murals alongside popular Ottoman ornamental motifs of the period, adds Tchitchileishvili.

Borjgali spirals are prominently chiseled into the supporting outer beams of Gulebi mosque, abandoned in the early 19th century.

In a neighboring valley, four borjgali motifs decorate the mihrab of Zvare mosque, built in 1834. Tulips, a popular Ottoman-era motif, feature prominently on the minbar's side wall and banister, while the gallery beams and columns bear Georgian braids and interlocking circles.

Despite these masterful carvings in both mosques, missing floorboards, gaps in rotting wood panels and moisture-laden beams indicate their fragile state.

Left: Cornstalks and an Ottoman steamship, signature murals left behind by Laz masters who decorated many of these mosques, flank the entrance doors of Ghorjomi mosque, which was completed in 1903. Right: Prayer beads hang at the mosque.

Mosque preservationist work through challenges

Although state agencies officially listed Zvare, Gulebi and 25 other wooden mosques in the region as cultural heritage monuments in 2008, their condition points to the chronic lack of governmental funds to preserve them. But some believe there is a lack of will too.

Nestan Ananidze, codirector of Solidarity Community, a nonprofit that works on minority rights in Adjara, notes tourist signs for churches are visible everywhere, but one can’t see signs for mosques.

As tourism makes inroads into the picturesque region that also hosts four UNESCO protected national parks, the village mosques remain invisible to most visitors, their presence rarely indicated.

In recent years, Solidarity Community has been working with local religious heads and heritage specialists to campaign for the proper rehabilitation and restoration of the mosques as unique examples of Georgian Islamic art.

Left: The abandoned Zvare mosque, which dates to 1834, exemplifies wooden mosques' resemblance to buildings with typical wooden masonry from the outside. Right: Tulips, a popular Ottoman-era motif, figure prominently in openwork detailing along a banister at the Zvare mosque.

Most Georgians identify as Orthodox Christian. While Adjarans are ethnic Georgians, other Muslim minorities in Georgia are descended from Azeri nomadic tribes or North Caucasian groups, and Islamic heritage is often seen as a product of foreign influence, according to Ananidze.

Solidarity Community’s media campaigns and tours of these mosques have helped introduce them to fellow citizens.

“So many fellow Georgians are amazed when they see these mosques, and they start to understand these ornaments came from the Georgian people,” Ananidze adds.

In late 2024, the Cultural Heritage Protection Agency of Adjara committed to restoring two early-19th-century mosques in urgent need of rehabilitation. Zvare mosque now has a new roof to slow down water damage, while another, Dzentsmani mosque, was recently deconstructed to be restored and rebuilt.

Although hopeful about these recent updates, Ananidze remains pragmatic and says her nonprofit must continue pushing local authorities for a unified plan and strategy to protect and preserve all surviving wooden mosques.

Osman Kakhadze, the 26-year-old caretaker of Beghleti mosque, demonstrates how the new chandelier is strung up to the mosque's original rusty iron pulley system. The mosque dates to 1870; its current decorations were added in 1926.

It is important to carry out joint projects in order to preserve these mosques, which represent the common cultural heritage of both [Georgia and Türkiye].

“We are a developing country. There is little budget, but we have to do what is possible,” she says.

Her nonprofit has assessed the rehabilitation needs of several mosques and published a list of low-cost interventions to restore and better protect them.

Turkish studies confirming the Georgian origins of the wooden mosques, also found across the border in Türkiye’s Black Sea region, where they are called Çanti mosques, bolster these efforts.

"The presence of motifs frequently encountered in Georgian medieval Christian iconology and Eastern Christian stone art, such as braiding, two- and four-striped braiding, basket weaving and walking figure eights, alongside Turkish-Ottoman motifs … support[s] the viewpoint that the masters of these mosques came from Georgia," says Alev Erarslan, who teaches the history of architecture at Istanbul Aydın University.

“It is important to carry out joint projects in order to preserve these mosques, which represent the common cultural heritage of both countries, and to restore them and pass them down to future generations,” she says.

Ananidze says Solidarity Community will continue its campaign for inclusivity and the recognition of Adjara’s Islamic heritage as an integral part of Georgia’s culture.

Scholars like Baramidze welcome the growing dialogue surrounding these long-overlooked mosques. He sees them as reflections of the country's multilayered and diverse past, and is optimistic about their future.

“These mosques are part of our history. [They are] part of our rich culture … [and] local memory. They have to be preserved.”

More From AramcoWorld

When Places Are Saved, So Are Traditions

Georgia's heritage revival doesn't end with architecture.

You may also be interested in...

Ramadan Nostalgia Requires Active Reconstruction

Arts

Artists demonstrate how Ramadan traditions endure through deliberate acts of memory and care.

Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, a Conversation With Food Historian and Author Nawal Nasrallah

Arts

In Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, Arab food historian Nawal Nasrallah breathes new life into an anonymously compiled 13th-century cookbook.

‘Home’: Arab American National Museum Celebrates 20th Anniversary

Arts

Arab American National Museum Director Diana Abouali says the facility—which is marking its 20th anniversary in 2025—in Dearborn, Michigan, has aimed to create a home for Arab Americans by preserving and presenting the history, culture and contributions of Arab immigrants as well as their native-born children and grandchildren.