The Age of Ivory

Some were found at the bottoms of wells. Some were scattered about palace rooms. Thousands of exquisitely carved works of ivory, all produced nearly 3,000 years ago in and around what is now Iraq, make up one of the most beautiful and enigmatic legacies of Assyria.

British archeologist and adventurer Austen Henry Layard may be best known for the discovery in 1845 of the colossal winged bulls from Nimrud that are displayed at the entrance of the Assyrian gallery at the British Museum. But that same year he found the first of more than 100 exquisitely carved ivory specimens—the initial pieces of a 2,500-year-old jigsaw puzzle that is still being put together today. In fact, it would take another century before the Assyrian capital from the ninth to seventh centuries BCE would yield the largest concentration of ancient worked ivory ever discovered, illuminating Middle Eastern art, culture and history, and earning the period the title “The Age of Ivory.”

It’s not just the splendor and sheer amount of worked ivory that captivates. Most of the highly artistic pieces were found in what first appeared to be the unlikeliest of places: in well bottoms, in the remains of warehouses or even strewn haphazardly about. Furthermore, despite being found in an Assyrian capital city, relatively few are of Assyrian origin or style.

“They’re incredibly beautiful,” says Georgina Herrmann, honorary professor and emeritus reader in Near Eastern Studies at University College London. “You can spend hours with them. They are a fabulous art archive that has been very little studied.” Herrmann is probably the world’s leading authority on the ivories found at Nimrud, as illustrated by her latest work, Ancient Ivory: Masterpieces of the Assyrian Empire, which appeared in 2017.

We’re having breakfast at the ornate Athenaeum Club in London, where Herrmann is a member. Petite and silver-haired with meticulous manners, she talks enthusiastically about her passion for the ivories she’s been studying, cataloging and publishing for decades.

“One of the things about ivories is that they look very dead in an exhibition case. You really need to see them in your hand, and also you have to remember how they were used,” she says. “Most of them were elements of furniture; you’d have sets of them on the backs of chairs, for example. They weren’t designed just to be looked at as an individual piece.”

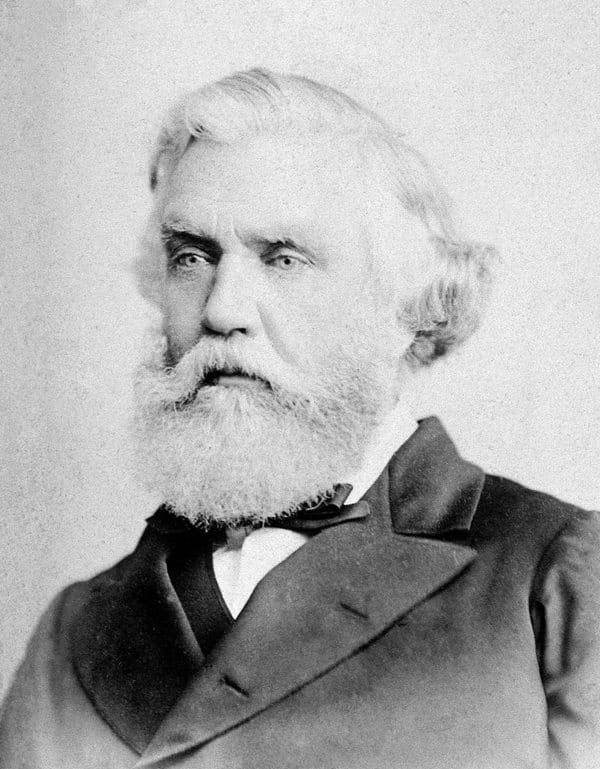

It was from this very club that Henry Rawlinson, a former British diplomatic resident in Baghdad, corresponded with Layard regarding additional funds to continue excavating at Nimrud and to work in nearby Nineveh. Layard had discovered the first of the ivories at Nimrud, 30 kilometers south of Mosul, in the autumn of 1845 when he cut the initial trench through what would be identified as the North West Palace of Ashurnasirpal, king of Assyria from 883 to 859 bce.

“In the rubbish I found several ivory ornaments, upon which there were traces of gilding; amongst them was a figure of a man in long robes, carrying in one hand the Egyptian crux ansata, part of a crouching sphinx, and flowers designed with great taste and elegance,” he wrote in Nineveh and its Remains, published in two volumes in 1849. (Although many of the plates in the volume of illustrations deal with Nimrud, Layard chose the title to appeal to a public that was familiar with biblical Nineveh.) Layard continued with his excavation of the palace, and by 1847 he had identified 28 chambers. One, which he labeled “V,” was “remarkable for the discovery of a number of ivory ornaments of considerable beauty and interest,” he wrote.

About a decade later, writes Herrmann, British geologist William Kennett Loftus found “an immense collection of ivories, apparently the relics of a throne or furniture,” at Nimrud in the very first room he excavated in an area showing fire damage. Appropriately, he named it the “Burnt Palace.” The ivories were then largely forgotten for almost a century—until Max Mallowan entered the picture.

Nimrud “will rank with Tutankhamen’s tomb, with Knossos in Crete, and with Ur.”

—archeologist Max Mallowan to his wife, crime novelist Agatha Christie

Mallowan, a professor of Mesopotamian archeology at the Institute of Archaeology, University of London, was intrigued with the ivories. He was a man who appreciated beautiful art objects and was seeking to start an appropriate major excavation. In 1948 he told his wife, famed crime novelist Agatha Christie, Nimrud “will rank with Tutankhamen’s tomb, with Knossos in Crete, and with Ur.” So he mounted a major series of campaigns at the site which lasted from 1949 to 1963 under the auspices of the British School of Archaeology in Iraq (bsai), now the British Institute for the Study of Iraq (bisi).

Mallowan focused his first efforts on the palace chambers where Layard had discovered his finest ivories. “We wanted to know not only how many fragments he had overlooked, but how the ivories had originally been situated,” he wrote in his memoirs. He and his team were soon rewarded, finding “one ivory of rare delicacy, a model of a cow … giving suck to a calf.” Then more ivory quickly filled the expedition’s dig-house.

Elated with the volume of spectacular finds, the bsai pressed on season after season. The greatest number of ivories came from an area where a vast building of over 200 rooms had once stood. Mallowan dubbed it “Fort Shalmaneser,” after Shalmaneser iii (859–824 bce), the Assyrian king responsible for its construction. Excavations commenced in 1957, and the variety of finds was striking.

“Among the most beautiful are the animals … oryx, gazelle and other horned beasts,” Mallowan wrote. The bsai team also excavated the Burnt Palace, where “of all the discoveries the ivories were outstanding.” A final tally of the Nimrud ivories is elusive, but Herrmann estimates the number runs well into “the tens of thousands.”

It was all, she writes, “an enormous jigsaw puzzle.” To date seven volumes devoted to the ivories from Nimrud—the bulk authored or coauthored by Herrmann—have been produced under the auspices of the bisi, with yet another planned.

The 14 seasons of British excavation, and subsequent Iraqi work at the site, were not devoted primarily to the search for ivories. The teams uncovered thousands of clay tablets with cuneiform text detailing daily life, and sculptures, paintings, seals, colossal carved stone figures and lavish royal tombs. However, the ivory pieces proved Nimrud’s artistic crème de la crème. As David and Joan Oates from Cambridge University put it in Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed: “[I]f one were forced to select a single category of object for which Nimrud stands out above all contemporary ancient sites, it would have to be the carved ivories.”

Julian Reade joined them at Nimrud as a junior assistant after graduating from Cambridge in 1962. “I had arrived more or less as a detached observer,” recalls the retired British Museum curator of the Department of Western Asiatic Antiquities and honorary professor at the University of Copenhagen.

I’m sitting with Reade on a park bench in sunny Russell Square, just a few hundred paces from the British Museum where thousands of the Nimrud ivories are kept. A dozen or so are on display for the public, including several pristine examples of winged sphinxes and goddesses, and the exhibition “I am Ashurbanipal: king of the world, king of Assyria,” running at the museum until February 24, shows a number of other prime examples. Herrmann is right: These are hauntingly beautiful objects of art.

Reade attests to the meticulous, painstaking work required to clean them and reveal their exquisite detail: “It was very tricky. Earth was firmly adhered to them and you didn’t want to nick the ivory removing it.” And, he says, it was a race against time to preserve the ivories as the soil would gradually harden once exposed to the dry air.

Agatha Christie regularly pitched in. “I had my own favourite tools; an orange stick, possibly a very fine knitting needle ... and a jar of cosmetic face cream ... for gently coaxing the dirt out of the crevices,” she wrote in her 1977 autobiography.

All of the excavated ivories belonged to the isbah, so it had to be decided which ones could leave the country. “The finds were divided into two groups,” explains Reade. “The director of the excavation together with the Iraqi director general of antiquities would lay out everything on a table basically balanced in two groups. Together they would decide which would go to the Iraq museum and which would be allocated to the expedition for export to the British and various other museums.” Luckily, there were a large number of duplicates, which facilitated the process.

Valuable pieces, including the mauling lioness, are now missing. But the British Museum’s sister piece remains, and Reade credits Mallowan for that. “Without his energy and drive, I don’t think anything like as much would have been done,” he says. “The very last time I saw Max was at the British Museum, and on the way out he paused in front of the lioness ivory he had found and looked at it for a long time. I very much thought he was drinking it in as one of his major achievements.”

Nimrud had a profound impact on Reade too: He went on to pursue a doctorate in Assyrian architecture, buildings and their decoration. Nimrud influenced “what I’ve done since then [and] has become part of my academic life,” he says.

Nonetheless, significant questions remain: Where did the ivory come from? How did this incredible treasure trove come to be at Nimrud? Mallowan believed it was sourced from the Syrian elephant, which may have been hunted into extinction. Herrmann, however, believes that most of the ivory must have come from Egypt, the Sudan or North Africa. “It’s one of those academic disputes,” she says.

Herrmann also reckons most of the ivories came as booty from conquered cities. “The ivory images were meant to protect people,” she explains. “They provided power. So if your city was conquered, then their power had clearly failed. The conquerors didn’t use the ivories but kept them because they didn’t want other people to have the signs of kingship.”

Herrmann says the political picture in the region at the time was volatile and complex. “You are looking at a huge area and a lot of different kingdoms, each producing their own visual and propaganda art, each slightly different. And then you had Assyria gradually sweeping in and absorbing them all, knocking them out. And after a while, they got knocked out.”

The Assyrian empire expanded rapidly in the early first millennium bce to control an area from modern Iran to the Mediterranean. Its power peaked around the 8th century bce. Then its heartland came under increasing attack from the Medes and the Babylonians. The empire finally crumbled in 612 bce when the allies sacked Nimrud. This is thought to be the reason so many ivories ended up in the wells—although one Iraqi excavator surmised they might have been lowered in baskets so they could be pulled up again later.

This tapestry of independent minor powers underlies the regionalism reflected in the art of the area, says Herrmann. And it is the art, specifically the ivories, that reveals the great wealth of these states.

Dating and sourcing the ivories calls for some creativity. “The ivories [the Assyrians] brought back were made in a number of different centers and we can’t tell which came from which center,” Herrmann says. “There’s no ‘Made in Birmingham’ stamp on them. But from stylistic analysis you can begin to group them.”

They can generally be sorted into three stylistic groups, Herrmann says. The first is Assyrian, characterized by similarities with the kingdom’s sculptures. In spite of their ivory hoarding, “the Assyrians were not great ivory lovers,” she notes. “They did carve some but it was very limited.”

“The ivory they used was that which they decorated with their own art,” she adds. “So the Assyrian style is very distinctive…. You’ll find it in ceremonial and royal areas” in the palaces and in Fort Shalmaneser.

Items of booty, gifts or tribute—usually stripped of any gold overlay by the Assyrians or their conquerors—are mostly found in storerooms.

Based on stylistic considerations, the second group is called Phoenician and shows a strong Egyptian influence; it’s the largest assembly found at Nimrud and includes winged deities and sphinxes. The Phoenicians were famed craftsmen with a long history of woodworking and, as active traders, had access to plentiful supplies of ivory and gold, writes Herrmann. All the conditions were right for the production of luxury goods designed for the court and temple. Panels in this style would have decorated furniture, the backs of chairs, footboards of beds, or chests.

The third group, based on sculptures found along the Syria-Turkey border, is called North Syrian. Academic debate starting in the 1970s added a possible fourth group: Syro-Phoenician, perhaps located in south or central Syria and including a number of style groups.

Working from these observations, Herrmann estimates probable dates for the ivories from the Mediterranean area at between 1050–800 bce, with production in northeastern Syria about 50 years earlier.

A striking and unexplained observation is how comparatively little ivory there is in Egypt, despite its artistic influences. “There is a group of ivories I call Egyptian because they look it,” says Herrmann. “But I had a specialist look at them—reading the hieroglyphs and things—and he said these aren’t really Egyptian. They are fake Egyptian even though they look it. He said nothing like them has been found in Egypt—which to me is surprising.”

This leads to other major puzzles with the ivories: Why are they found in such massive numbers at Nimrud and nowhere else; and did the Age of Ivory end with the sacking of Nimrud?

“It’s accidents of discovery,” offers Herrmann. “We don’t know how much ivory continued to be used because we haven’t found other Nimruds. The finds are so enormous that people think this must be the only one.”

That’s the nature of archeology: Assumptions are constantly upended. Herrmann uses an analogy: “Nobody thought there would be tombs of the queens at Nimrud until they were found in the North West Palace.” And that led to overturning another assumption: It had been thought that the ivories were mostly feminine items. But very few were found in the queens’ tombs. Ivory cosmetic containers, for example, were found only in kings’ tombs. “They were completely a masculine thing,” Herrmann says. “The queens were richly furnished with a wide variety of grave goods; the absence of ivory must have been deliberate.”

“It’s a large and complex subject which requires a lot of additional study,” she adds. But her immediate priority is to continue cataloging the ivories. “My main aim was to try and rescue the ivories because when Max died, thousands of pieces had not yet been described in his three completed volumes. What I’ve published is not yet complete.”

The “Age of Ivory” moniker associated with Nimrud is justified by the record. “[Nimrud] completely changed the picture,” Herrmann says. “Nobody had found anything like it before—not in Egypt or anywhere. The amount they used is just astonishing.”

Reade agrees. “I think it is fair to say that the Nimrud ivories are one of the great stories of the ancient world and they haven’t received the academic attention they deserve,” he says. “The Age of Ivory is a powerful chapter that stands alone in archeology.”

You may also be interested in...

Spotlight on Photography: Drinking in Türkiye’s Coffee Culture

Arts

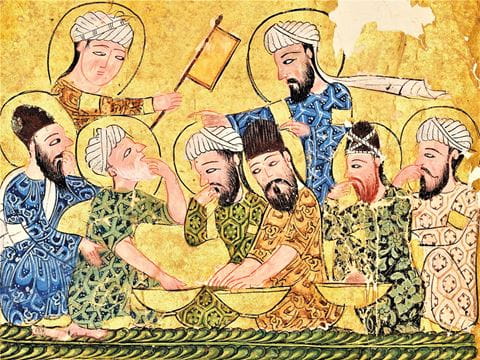

Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

Arts

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.

Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, a Conversation With Food Historian and Author Nawal Nasrallah

Arts

In Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, Arab food historian Nawal Nasrallah breathes new life into an anonymously compiled 13th-century cookbook.