Beirut Sounds Like This

An alchemy of creativity and adversity, the Lebanese capital’s indie/alt music scene feels ripe for global gold. Find some of our starter tracks on page 22 to listen to while reading and decide for yourself.

“When I first began making Oriental music as a teenager, it was the way foreigners fantasize it,” says Zeid Hamdan, leaning back into the couch with a cup of chamomile tea. Though it is nine in the morning, he has already wrapped up one meeting, and in an hour he has to be at the studio where he is set to put in an eight-hour day producing musician and film composer Khaled Mouzanar’s new album.

At a free concert in Beirut’s Karantina neighborhood, Hamdan and Egyptian singer Maryam Saleh keep fans on their feet.

There is no account of the contemporary Beirut alternative music scene that doesn’t begin with Soap Kills, with how it felt to turn on the radio, after years of nothing but news-report jingles, more traditional Arabic tarab music and the beloved and wholesome Lebanese diva Fairuz, and hear something that felt both entirely of now and of us. Though the son of Fairuz, musician and playwright Ziad Rahbani, did much in the 1980s to pave the way, mixing politically conscious lyrics delivered in Lebanese dialect with Oriental jazz orchestrations, Soap Kills was the postwar generation’s answer to what it meant to be at once both homegrown and contemporary, tearing down and stepping past the war-enforced contradiction between those two terms.

Beirut today, says Hamed Sinno, lead vocalist of Mashrou’ Leila—currently the Arab world’s biggest pop-rock band—“is the experience of being in a place and yearning for it at the same time.”

“Listening to Soap Kills as a kid changed everything for me,” says Hamed Sinno, lead singer of Mashrou’ Leila, inarguably the Arab world’s biggest pop-rock band right now, having premiered its latest album with a concert in London’s Barbican Theatre last November that was two-way live-streamed to Beirut, so important was it for the band to include Beirut in its debut. “Yasmine’s vocals … I’d never heard Arabic used and sung like that before.”

This, explains Hamdan, was a conscious decision on the part of Soap Kills and the crux of its local appeal. Both Zeid and Yasmine had grown up abroad with parents who had fled the war to Europe. Despite, or perhaps because of, having grown up in a house where his parents never listened to Arabic music, never read Arabic books and rarely even spoke to him in Arabic, Zeid came back to Beirut “fantasizing about being an Arab and making Arabic music.”

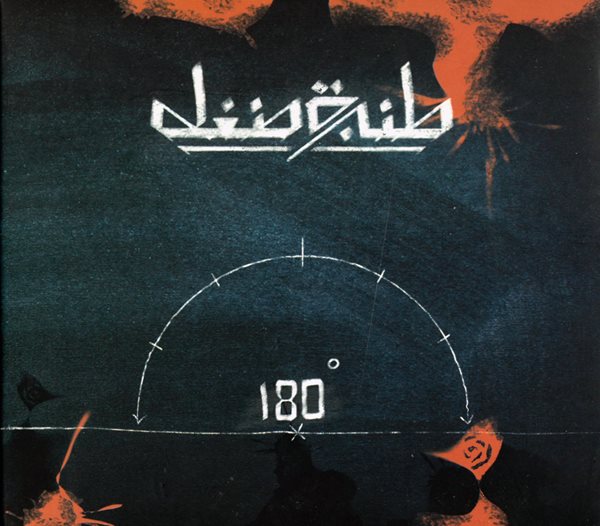

Guitarist Tarek Khuluki, drummer Dani Shukri and lead vocalist Khaled Omran are Tanjaret Daghet (Pressure Cooker). The trio arrived in Beirut from Syria in 2011 and released 180°, its first album, in 2013.

But the first songs he wrote, with a band called Lombrix (through which he met Yasmine) dissatisfied him. “It was exotic Arabic music, using the cliché scales,” he says. He began listening to Arabic music in earnest, spurred on by Yasmine, who played him classics by Abdel Halim Hafez, Asmahan and Um Kulthum, and when he sat back down to write, it was with the idea that it had to be something he wanted to listen to. Writing Arabic music, he came to see, was not so much about Arabic scales or quarter tones, but addressing an Arab audience, and so it had to be sung in Arabic.

This was where Soap Kills enacted its musical revolution. Arabic tarab music is all about the singing—and what singing it is: grand, emotive, impassioned and virtuosic, with sustained notes that leave both audience and singer breathless. To hear a woman’s voice singing like Yasmine’s—minimal, restrained, intimate, sometimes almost whispering—signaled a new kind of Arabic music that played with and responded seamlessly to the electronics and samples layered behind the voice. It was not so much fusion music as music arising from immersion in and knowledge of two separate cultures, made by artists who were the hybrid children of a Beirut marked by immigration, separation, disjointedness and loss, but also postwar homecoming and tenuous aspirations for a future that might repair those ruptures.

“In my opinion, Soap Kills were the first,” says Ziad Nawfal, “but they weren’t the only ones.” Nawfal is a walking, talking archive of the Beirut alternative-music scene, having come of age right along with it, documenting it through a radio show he began hosting in the ’90s as a teenager and then later, in 2009, creating a record label, Ruptured, that grew out of the show and bears the same name. In addition to his roles as radio host and label owner, Nawfal is also a dj, record producer and promoter, organizing concerts and performances. More than that, though, he is a huge music buff and a committed supporter of local musicians, showcasing both established talents and young newcomers who approach him with their demos on his radio show.

He cites the noise/punk/experimental rock group Scrambled Eggs and the rap duo Aks’ser (Wrong-way Traffic) as other major players on the emerging scene in the early 2000s. “Before that,” he says, “I played foreign music on the show, and then when these bands came along, I started playing local musicians. When I first started out, I would play one or two local bands during my show. Now, I can compose an entire dj set out of only local musicians.”

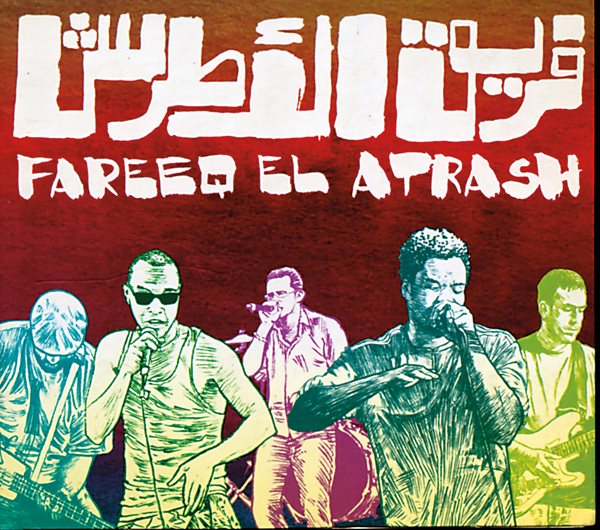

Bassist and beatmaker for the rap/hip hop crew Fareeq el Atrash, John Nasr explains that although they rap often in Arabic, “We don’t really use Arabic beats in our music. If we were to play with Arabic music or beats, we would have to do it in such a way that it would be as accomplished as the rapping.”

The scene grew and thrived as artists played with music and sounds from hard rock to electro to experimental improvisation (a genre that has established such a devoted following, thanks to its yearly festival Irtijal, that it has gone from a single day of performances in 2001 to almost a full week of some 20 concerts by both local veterans and international artists). At the end of 2002, a showcase concert was held at Beirut’s Music Hall, a shiny new venue built on the former no-man’s land that once divided the warring halves of Beirut, and in 2003 a compilation was put out by the alt-music store La CD-thèque, where Nawfal worked at the time. The compilation, Beirut Incognito, was a who’s who of the young Lebanese bands that had started in the late ’90s. It was an acoustic portrait of Beirut at the time: eclectic, all over the place, impossible to define, but above all exuberant, willing to experiment, try anything. “It was magnificent,” says Nawfal. “It blew up all expectations and preconceived ideas. For the first time, we had the feeling that something different was happening, that we were opening up and going places.”

It was the last time all the notables would be able to fit on a single record.

DIY

As the scene developed, it broke off into little genre “spheres,” as Nawfal puts it, each with its own small, growing and dedicated legion of fans. The political upheaval of 2005 and 2006 in Lebanon, which saw both the shocking assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri and a 33-day assault on the country by the Israeli army, also had reverberations in which the music scene, with some bands breaking up as their members left the country to seek more stable lives elsewhere, and different bands coming together around that time with a sense of urgency no doubt informed by the situation.

After discovering and coproducing Mashrou’ Leila’s debut in 2008, Jana Saleh has worked as a popular dj and producer for singer Aziza. Trained at Berklee College of Music in Boston, she credits the influx of Syrian musicians to Beirut for bringing “strong, academic musical know-how to the scene.”

The alternative-music scene in Beirut is an alchemy of creativity and adversity. It’s not so much because of the fraught state of the region (though that certainly plays a role) but due also to the void of an industry or government-sponsored arts initiatives. While there is a giant regional music industry that supports traditional Arabic pop and tarab acts, it is slickly corporate, incredibly lucrative and tightly controlling, with composers, musicians and videographers associated with particular labels, like Rotana, for example, hired to create and manage a singer’s brand and sound from A to Z. By contrast, the alt scene is entirely diy, with improvised venues, musicians exchanging favors, producers lending out their studios, bands paying out of pocket to print their own records, and friends and supporters offering their networks for distribution. It is much like everything in Beirut: a loose, self-made, often chaotic and collaborative solution to a structural problem.

It is precisely this chaos and collaboration, however, that some cite as the draw to working and creating in Beirut. Raed El-Khazen is a musician and producer who studied at the Berklee College of Music in Boston where he met Jana Saleh, a fellow Lebanese student, who happened to be the daughter of his favorite teacher. The two kept in touch over the years as they both moved to New York and worked in music and production—El-Khazen playing with bands and recording his own music, Saleh working in digital distribution and new project development at VP Records. After she moved back to Beirut in 2008, she gave El-Khazen a call: She had “discovered” a group of young musicians who had a rough but exciting sound and the talent and drive to grow into something really special. Moreover, they had something she hadn’t encountered on the indie scene in Beirut in a long time: They sang in Arabic. Did he want to come to Beirut and work with her on producing them?

This was how the two of them came to set up their own studio, B-root, where they arranged, recorded and produced Mashrou’ Leila’s eponymous debut album.

While El-Khazen initially planned to be back and forth between New York and Beirut, “once I got here, I found I really wanted to just be here. I didn’t want to be in New York anymore. It’s much freer here, easier to be innovative, creative, to cross boundaries. There’s no industry and hence a nonchalance. People are willing to try things because there’s no consequences, no guy who’s going to tell you, ‘You can’t do that because no one will play it on the radio.’”

After finishing the Mashrou’ Leila album, El-Khazen and Saleh went separate ways, drawn to different projects and artists, though they often consult with one another and help each other out. In 2014, El-Khazen met Samer Saem Eldahra, aka Zimo, a young visual artist who’d moved to Beirut from his native Syria to escape the war. Zimo was also creating electronic music under a project entitled Hello Psychaleppo: dark, twitchy, psychedelic concoctions of bass-heavy beats and hallucinatory synths infused with keening Bedouin mawwals and filches of old tarab tracks, what Soundcloud has categorized as “electro-tarab,” a subgenre that Hello Psychaleppo seems to singlehandedly own. Very quickly, he took the underground scene by storm. “I heard this guy’s stuff and I was just blown away,” says El-Khazen. “I knew I wanted to work with him immediately.”

Saleh, meanwhile, who is also a popular dj on the Beirut scene, found her new muse in Aziza, a young Lebanese singer-songwriter who “combines classical Arab tarab rules of composition with pop.” Saleh approached the Aziza project with relish and playfulness, eager to develop a sound, album and persona with a narrative modeled on the classic Lebanese and Egyptian musicals of the ’50s and ’60s. They recorded a studio album followed by a live album.

Broadcasting online, Radio Beirut also showcases live and dj performances in the pulsating Mar Mikhail neighborhood. DJ, label owner and radio host Ziad Nawfal says that in the 1990s, “when I first started out, I would play one or two local bands during my show. Now, I can compose an entire dj set out of only local musicians.”

“The approach to the studio album,” says Saleh, “was how to take the traditional compositions of old Lebanese music and freshen them up, while the live album was how to take that freshening up and to deconstruct it.” The live album, she says, actually achieved something unique thanks to the wave of Syrian musicians who came into the country around that time. “In Lebanon we have a more conceptual approach to things. The Syrian musicians brought strong, academic musical know-how to the scene. They have an education in Arabic music through their conservatory that we don’t even have access to here, and they’re also culturally more in touch with those roots.”

One of those musicians was Tarek Khuluki, the wunderkind electric guitarist with the Syrian-origin rock band Tanjaret Daghet (Pressure Cooker), whose albums El-Khazen has gone on to produce. The rehearsal space used by Tanjaret Daghet—guitarist Khuluki, bassist and keyboardist Khaled Omran and drummer Dani Shukri—happened to be right next door to El-Khazen’s underground Hamra Street studio. He was so impressed with what he heard—literally through the walls—that when they approached him, he immediately agreed to work with them. Their second album, currently in the mixing stage, is a heady mix of hard-edged rock with ferocious guitar solos, raucous drums and vocalizations that veer eclectically between boisterous rock-n-roll and soulful mawwal-type chanting.

While several producers talked about the rich addition Syrian musicians have brought to the Beirut scene with their musicianship and relentless hard work, it would be remiss not to mention the difficulties they must navigate. A large part of their modest earnings must cover the fee for the annual residence permits that allow them to remain in the country, and each person must secure a local sponsor to renew that permit—not to mention that working at all requires additional, hard-to-get papers and permits. Not surprisingly, many found help within the music community, with Lebanese producers often stepping in to sponsor Syrian musicians—all adding yet another layer to what it means to be collaborative in Beirut.

The Language of the “Arab Street”

John Nasr is the bassist and beatmaker for the rap/hip hop crew Fareeq el Atrash, which he describes in one breath as “a live hip hop band modeled after the classic funk bands from the ’60s and ’70s with musicians, rappers and a beat boxer taking a somewhat improvisational call-and-response approach.” The band came together around 2006, when Nasr began working with rapper Edd Abbas and then later with whizz beatboxer FZ and the Syrian-Filipino rapper Chyno (who recently released a solo album, Making Music to Feel at Home, garnering international attention and securing a European tour). A third rapper, Qarar, has now joined their lineup. Abbas and Qarar rap in Arabic, each with his distinctive rhythm and style, while Chyno switches between Arabic and English. “Edd was one of the first rappers for me to really crack the code of making Lebanese dialect sound good in rapping,” says Nasr.

Tanjaret Daghet's guitarist Khuluki relaxes while Omran practices in the apartment shared by the trio-in-exile: Each band member left a family and friends in Syria. They are now at work on their second album of ferocious guitar, raucous drums and vocals that veer eclectically between boisterous rock-n-roll and soulful mawwal-type chanting.

The band’s sound and beats are much influenced by Western and African American styles, and they often eschew samples in favor of jazzy, funky, melody-rich layers that create an expansive soundscape against which the rappers throw down their rhymes. Their approach is lively and humorous even when the subject matter is dark, sometimes playfully quoting rap classics with their own signature twist, such as the infamous hook from the 1979 hit “Rapper’s Delight” on their track “Njoom ‘Am Te’rab” (“The Stars Are Getting Closer”).

“We don’t really use Arabic beats in our music,” says the California-born Nasr, explaining that the band members prefer to rely on what they know and, more importantly, understand, in terms of sound. “We never want it to sound like a gimmick. If we were to play with Arabic music or beats, we would have to do it in such a way that it would be as accomplished as the rapping.”

This does not mean that the band, like many others, doesn’t proclaim and wear a staunchly regional, rather than local, identity. Besides the fact that they rap (predominantly) in Arabic, they also collaborate often across regional lines, both as a band and as individual producers and beatmakers with rappers and emcees in Jordan, Palestine, Egypt and Syria.

There are also frequent collaborations between the rap scene and the electronic and indie scenes. Chyno collaborated with a number of musicians on his solo album, including Carl Ferneine from Loopstache, “an electro-indie project, mixing folk, swing, funk with electronic beats.” Jawad Nawfal, brother of Ziad, is an avant-garde electro artist who currently creates under the name Munma but began playing live in the early 2000s with other projects. Munma has released 10 albums, under his own name and with different collaborators, including hip hop artist El Rass, who often raps in fus’ha (classical Arabic), recalling and then breaking the formal conventions of Arabic poetry.

A number of bands echo Hamdan’s assertion that “making Arabic music is primarily about addressing an Arab audience,” dismissing the need to work with traditional Arabic scales and compositional rules in favor of a lyrical approach that voices their ideas and concerns predominantly in Arabic.

“I grew up in a really ‘Western bubble,’” says Hamed Sinno, “attending American schools and an American university.” He describes the shock of the 2006 war and the ways in which doing volunteer relief work at the time really sharpened his gaze, bursting that bubble for good. “So when I started writing music, I knew I would only write in Arabic, even though I could barely manage it when I first started out. I still write mostly in English and then I look for the best translations. I have at least five translation tabs open on my computer at any given time.”

Jamming, collaborating and mixing it up Beirut-style, Raed El-Khazen, center in red shirt on guitar, producer of Hello Psychaleppo and Mashrou’ Leila, is backed by Tanjaret Daghet's Omran at far left and drummer Shukri while Khuluki plays keyboards. All joined Walid Sadek (white shirt) on trumpet at the Beirut Jazz Festival on May 1.

It is no small feat, considering Mashrou’ Leila’s powerful lyrics and the way Greek myths are referenced with the same ease as old Egyptian pop songs (the song “Djin,” off their latest album, Ibn El Leil (Son of the Night), is a case in point). In fact, conscious lyrics are a distinctive characteristic of many bands on the scene. Mashrou’ Leila, Fareeq el Atrash, El Rass, Tanjaret Daghet, the Arabic folk and experimental musician Youmna Saba, Edd Abbas (as a solo act) and Chyno all address the personal and collective challenges of navigating a landscape marked by shift and fracture, highlighting the ways in which the personal is political, but also how, in the Arab world, the political is highly personal, as regional events reverberate through individual lives.

Chyno’s verses, for example, in “Ballad of an Exodus,” a track off of Making Music to Feel at Home, eloquently excavate all these multiple layers, positing “home” as a place where “you get out of your comfort zone.” Written during a stint in Barcelona, questions of homeland, identity, responsibility and one’s place in the world echo off of and inform one another, with exile laid atop exile: “My body on a bench in Barcelona’s Paseo Picasso/Cuz this my Blue Period, my mind travels to Damascus corners/Tagging walls in Bab Tuma, manifesto for a New Syria.” Later in that same verse, the situation in Syria, where Chyno grew up, becomes even more personal as the war and its dangers creep closer while his body remains in Barcelona: “Yeah I got mail last month, inbox filled up with texts/‘The old milkshake store we use to chill with our friends/the one in Shaa’lan just got bombed/inshallah we won’t be next.’”

Giving Back

While there is no “Beirut sound,” per se—at least not yet—according to Nawfal, Saleh and El-Khazen, who all seem to agree that the scene has not quite yet matured enough to yield something that can be wholly called its own, there is a Beirut ethos. Beyond the homegrown “industry” inside which all indie musicians and producers here operate, where people must help one another out by necessity, the idea of cooperation extends beyond the material and into something more abstract and idealistic.

“I need to succeed in such a way where I feel I’ve reached a place where I can benefit somebody else,” says Chyno. He credits Fadi Tabbal, musician and founder of Tunefork Recording Studios, as a major force in helping get his album made, not just for his musical knowhow, but also for his generosity. “He basically gave me the studio for free, handed me the keys and let me go mix there on my own when I needed to. It was above and beyond anything I expected.”

Nawfal is motivated by the same sense of mutual responsibility. “I have a role,” he says in reference to his support of local musicians. “It’s my part, my duty.”

Raed El-Khazen, likewise, expresses a sense of guilt at his recent decision to go back to New York to focus more on creating and performing his own music. Ironically and sadly, he blames the same sense of chaos that initially attracted him so much to the Beirut scene as that which now drives him away from it, emphasizing that the flipside of the disorderliness that can nurture creativity can also be a lack of a sense of discipline that spills over toward nihilism. Still, he’s not done with the city yet. “I’ve given back enough,” he says, and then, pausing for a few beats, adds, grinning: “For now.”

Zeid Hamdan, in addition to his output with his bands The New Government and Zeid and the Wings, has also built a career based on collaborations with other musicians, giving workshops in Congo, Guinea and Algeria on how to produce albums with minimal production equipment and on a shoestring budget, and working with other musicians from the region, such as the Egyptian singers-songwriters Maii Waleed and Maryam Saleh, each of whom he has cut an album with.

“Sure, there are egos and competitiveness and all the usual things you’d find when there are a bunch of artists working in a small scene. Still, I don’t know of anyone who has had to pay another musician to get them to work with them,” says Nasr.

An occasional duo since 2012, Egyptian hip hop singer Maryam Saleh and Zeid Hamdan play for free in the Karantina neighborhood.

The Misguided Search for an “Authentic” Sound

It’s tempting to describe a lot of the music coming out of Beirut as a type of fusion between “Western” and “Arab/Oriental” sounds. But that’s a lazy shortcut more focused on maintaining binaries rather than acknowledging their utter meaninglessness, particularly for a postwar generation hyper-aware of its Arab roots and the Western influences that have long been part of the city’s urban fabric, and more importantly, a generation making conscious choices about how to mix elements from the various cultures it identifies with.

Almost equal to the number of artists making music that plays with and redefines concepts taken from Arab roots, there is also a considerable number who don’t think twice about that approach as they make music you’d be hard-pressed to identify by anything other than its pure musicianship and production value. That, too, indicates a creative freedom unconstrained by expectations of what one “ought to sound like.” Rock acts like Who Killed Bruce Lee and The Wanton Bishops, who recall LCD Soundsystem, Queens of the Stone Age and The Black Keys, or folk acts like Postcards and Charlie Rayne, who have echoes of Belle and Sebastian, Kings of Convenience and Bob Dylan: All write lyrics so competent in imagery and references you’d swear they’d just stepped off the streets of a small North American town.

“If I was forced to describe Beirut,” says Hamed Sinno, “I’d say it’s the experience of being in a place and yearning for it at the same time.”

That’s a fitting characterization of a city marked today not so much by the destruction wrought by war but the rampant reconstruction that swallows up the past as wholesale as any bomb. Still, whatever corporate razing there has been, attempting to numb the soul of the perturbed city, these are musicians determined to never let Beirut forget where it came from and where its place is in the now and future worlds. Beirut, port city, always a mix of everything, stubbornly and proudly undefined and indefinable, also has its private yearning, for a sound, for an identity, for a persona it can call its own, even if that persona is just the ability to perfectly mimic something else, without a trace of “foreignness.” That interplay, ongoing and endless, is in perpetuity the sound of Beirut.

About the Author

George Azar

George Azar is author of Palestine: A Photographic Journey (University of California, 1991), co-author of Palestine: A Guide (Interlink, 2005) and director of the films Beirut Photographer (2012) and Gaza Fixer (2007). He lives in Beirut.

Lina Mounzer

Lina Mounzer is a writer and translator living in Beirut. Her fiction and essays have appeared in Bidoun, Warscapes, The Berlin Quarterly and Chimurenga, as well as Hikayat: An Anthology of Lebanese Women's Writing, published by Telegram Books. Her favorite way of listening to music is through earphones while walking in the city.

You may also be interested in...

Artichokes to Ricotta: How Arab Rule Changed Sicilian Cuisine

Food

The cultivation methods, crops and dishes that Arabs introduced in Sicily not only survive but thrive today through foods that are integral and widely celebrated.

Spotlight on Photography: Drinking in Türkiye’s Coffee Culture

Arts

Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

Arts

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.