The Fragile Songs of the Sumatran Rhinos

“The more I know, the more I love about the Sumatran rhino,” says veterinarian Zulfi Arsan about the smallest and oldest rhino species. With only a few dozen left in the wild, captive breeding may offer the rhinos their best—and perhaps only—hope.

At four o’clock in the morning on May 12, 2016, Zulfi Arsan balanced himself on a tall fence post, poised to jump into a pen with a rhinoceros.

A minute passed. Then, a breath. And another.

Thus was Delilah born, the youngest Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, the smallest, oldest and most endangered species of rhinoceros in the world. With fewer than 100 left of her kind, her first breaths gave hope that Sumatran rhinos still could be saved from extinction, largely thanks to advances in science and the day-to-day work of men and women like Arsan.

Lanky and handsome with a black beard and smiling eyes, Arsan, 42, has a ready grin, and in conversation he can jump easily from the technicalities of Sumatran rhino physiology to a chat about a particular animal’s personality.

“The more I know, the more I love about the Sumatran rhino,” Arsan says. He grew up with animals, both wild and domestic—including a favorite pet heron. Having decided to be a vet at a young age, Arsan graduated in 2003 from Bogor Agricultural University in West Java. As a student, he interned at the srs, located deep inside Way Kambas National Park in southern Sumatra. In 2014 he became the sanctuary’s head veterinarian.

When he tells them goodbye, he sets out on a nine-hour trip that plods though Jakarta’s traffic, ferries across the Sunda Strait and then navigates potholed, sometimes-flooded roads through the rainforest.

“As a father and a husband, it is hard to be away from my family. They need me, and also I need them,” Arsan says. “But we have to do it, and they also understand and [are] proud for what I am doing here.”

For the rhinos, his job carries the highest of stakes.

There are few big mammals on the planet today closer to extinction than the Sumatran rhino. Only the vaquita porpoise, in Mexico, is closer—about a dozen vaquita are thought to remain.

While officials estimate there are still around 100 Sumatran rhinos are left in the wild—down from some 200 a decade ago—most independent experts believe the number is smaller, not more than 80 and possibly as few as 30. These are spread among four geographically disconnected populations. No one really knows if, with these numbers, any of the populations can prove sustainable.

This makes Arsan, the team at the srs and others like them the best hope for the species. At the srs, each of the seven rhinos lives in its own 10-hectare enclosure. Two of them— Andalas and Ratu—have produced offspring, in 2012 and 2016, respectively.

While Arsan works to help his charges create new life, across the Java Sea, in the Malaysian state of Sabah in northern Borneo, another vet is doing all he can to preserve a life.

Zainal Zahari Zainuddin has spent the last few months trying to heal a Sumatran rhino named Iman, one of two rhinos housed by the Borneo Rhino Alliance (bora). She and a 30-year-old male named Tam are believed to be the last Sumatran rhinos of Malaysia.

Iman was captured in 2014 after a camera trap revealed her traveling route. With a pit dug and covered, the team waited eight anxious months before they safely captured her and flew her by helicopter to the bora facility.

On first inspection, Zainuddin recalls that she looked pregnant. But it turned out to be a uterine tumor, a common problem for female Sumatran rhinos linked to the scarcity of mates.

Zainuddin, 59, came to bora in 2010 with 15 years of experience with the species. He knew something was wrong when Iman refused to leave her wallow.

“When they are sick, they always go back to the wallow,” says Zainuddin, who describes a wallow as a kind of “sacred place” for a rhino: Every Sumatran rhino builds one by digging out a puddle where it can enjoy a comforting mix of mud and water.

Eventually, Zainuddin and the bora staff were able to coax Iman, by then also dangerously dehydrated, out of her wallow into her night quarters, where the bora medical team could attend to her.

Iman’s tumor had ruptured. Zainuddin feared she wouldn’t pull through.

“Some days we gave her 15 liters of fluid, and it took us eight hours to finish 30 bottles,” says Zainuddin. “It took us almost two months to get her back to near normal condition.”

The Sumatran rhino is unlike any other. Although a full-grown one weighs in at nearly a metric ton, that’s only half the weight of male African white rhinos, which also stand half a meter taller at the shoulder. A Sumatran rhino also sports a shaggy coat of sometimes-reddish hair. While it has two horns—hence its genus name Dicerorhinus, Greek for “two-horned rhinoceros”—it’s not related to Africa’s two-horned rhinos nor to either of Asia’s, the Javan or Indian rhino.

Junaidi Payne, executive director of bora, calls the Sumatran rhino “the last living relic of the Miocene era,” which lasted from about 23 million to five million years ago—ages before we humans showed up. As a genus, he explains, Dicerorhinus split off from other rhinos around 20–25 million years ago. Despite being little known by the global public, there is nothing remotely like Dicerorhinus left on Earth.

“The Sumatran rhino is particularly special because it is the most ancient of the remaining rhino forms,” says Payne. “Most significantly, it represents a genus, not just a species or subspecies or race of rhinos.”

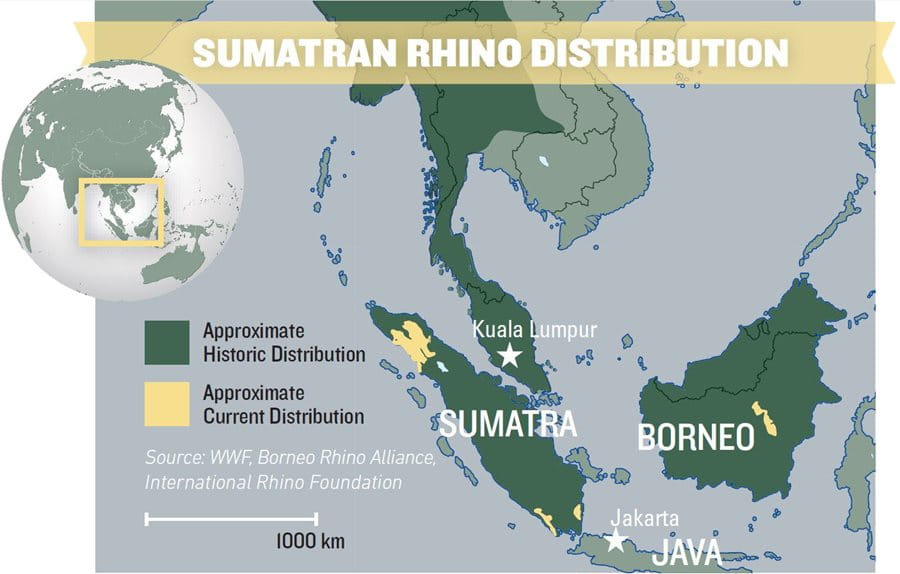

Two of its four surviving populations are in southern Sumatra, in Way Kambas National Park, where the srs is located, and in Bukit Barisan National Park. A third population survives in remote Aceh, at the northern end of Sumatra. A fourth population, discovered in 2013, lives across the Java Sea in Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo. The Bukit Barisan and Kalimantan populations are the most fragile—so much so that they may be nearly, or even already, gone.

Historically, the Sumatran rhino had ranged widely in southeast Asia, as far north and west as Myanmar, Bangladesh and India. Millennia of hunting, slaughter for its horn and deforestation meant it has been all but wiped out, one by one. Yet despite this dire picture, a recent genetic study suggests that the Sumatran rhino has been struggling against extinction since 9,000 years ago, when scientists estimate a minimum of 700 survived climatic changes and, likely, hunting by early humans. In many ways, it’s amazing they had survived the Pleistocene (2.5 million to 12,000 years ago) at all when other large mammals of the epoch, including mammoths, giant sloths and wooly rhinos, had not.

“They tame easily to you,” says Zainuddin. “They can associate to you and … they will accept you within the species. You can go close to them.”

This trust gives keepers the ability to train the rhino to come when called and to lie down passively when, say, they need a footbath or another procedure. Arsan calls them “clever” animals that “can learn.”

“Tam is the perfect gentleman,” Zainuddin says. When Tam eats, he always sniffs the food first and never goes “for your hand.” (In contrast, he says, Iman is a “shredder.”)

Tam has even learned to open his night-stall door by lifting the bolt with his head and moving it aside.

“He does it so confidently,” says Zainuddin. “One flip, second flip, and door is open. He just pushes [the] door in, and he walks in. He’ll make a noise, calling for the keepers.”

Still, behavior depends on context. Sumatran rhinos are malleable and calm in their pens because they have come to associate them with human territory. But in the wild, Sumatran rhinos will be protective of their territory.

“Every keeper and I treat the rhinos as family,” says Zainuddin. “They are never pets to us. We understand their feeling and their moods.” For example, he adds, when they are ill, “they let us handle them, and they give in to us, knowing we want them well. [They] can sense this. They are survivors and never give up hope as long as they know we are there for them.”

Both Zainuddin and Arsan stress that each rhino has a distinctive personality, and bonds to its keepers. Zainuddin says that when he and his colleague leave the pen for a time, they hear Iman “yelling from the gate, calling for them.”

In addition to snorting through its nostrils, a Sumatran rhino produces a sound from its larynx that experts compare to a singing whale or a whistling dolphin, as if the rhino is squeaking out a tune.

Arsan says he believes the rhino’s “song” is commonly used when the animal is “asking permission.” He says the rhinos tend to sing when they are waiting to be fed fruit, or wanting to leave their pens to go back to their wallows. A calf will sing out if it loses sight of its mother.

But aside from a short study in 2003 in the Cincinnati Zoo in the us, no one has researched the songs of Sumatran rhinos.

“There is so little known,” says Susie Ellis, executive director for the International Rhino Foundation, which helps manage the srs.

“Everything that we know about their biology has been learned in the captive setting because it’s just very, very difficult to study [in the wild].”

Given their rarity and timidity, very few experts have even actually seen a wild Sumatran rhino. Neither Arsan nor Zainuddin nor Ellis have ever seen one. Payne saw one, once, in 1983.

This paucity of knowledge makes support for captive breeding especially challenging. In the 1980s and 1990s, conservationists captured around 40 Sumatran rhinos for captive breeding, but it took 15 years just to begin to understand how they bred. By that time most of those captured had died.

Arsan explains that Sumatran rhino females are “induced ovulators,” which means they require something outside themselves to kick off ovulation. Biologists still aren’t certain what the female needs, but they suspect that natural breeding behavior—chasing, fighting, ramming and wallowing with a male—activates the required hormones. This is difficult to impossible to trigger if no male is around, and doubly worrisome given the high risk among females—such as Iman—for uterine cancer if they do not breed.

“I think the normal cycle for female [rhinos] is that they are pregnant, have a baby, and then wean and then are pregnant again,” Arsan says. “Waiting is not normal.”

Tumors can lead to infertility. This has likely proven catastrophic: As wild populations declined, surviving females would meet fewer males, likely leading to a more frequent incidence of uterine tumors, all hastening the demise of the population.

Uterine cancer has also plagued captive populations. Last summer Zainuddin had to euthanize Puntung, bora’s other female. Puntung, who had survived losing a foot in a snare as a calf, suffered from both uterine and skin cancer.

At the end, says Zainuddin, she couldn’t even sing.

“That’s when I had to make the decision that we can’t let her go on like this,” Zainuddin says. “It’s a really hard decision to make, but it had to be made because she was suffering.”

Fortunately, Iman’s time has not come: Her condition has only improved. She has been allowed to return to her wallow, and she is eating close to her regular amounts. Still, Zainuddin is skeptical she will ever give birth.

Susie Ellis, International Rhino Foundation

“We shouldn’t give up,” Zainuddin says, noting he thinks extinction can be avoided if Indonesia “acts soon” to do more.

For Arsan, his relationship to the rhino requires a dichotomy. On the one hand, he says, he loves them each individually, sometimes as if they were his own children. On the other, he knows he also has to treat them professionally as a mammal population on the brink of extinction: He has to keep his gaze on the horizon and do everything possible to keep the species going.

“We are aware how important our work is,” Arsan says. “And we are also aware … there [are] many pressures that come with it. All eyes and ears will go to us ... if bad things happen.”

In the face of such scrutiny, he and his team focus on “doing our job” and “keep[ing] our protocols.” They are in constant contact with experts around the world, and they work hard to learn from the mistakes of the past.

History proves that dedicated people can save a species this close to extinction. Both the European bison and the Arabian oryx at one time survived only in captivity. From a population that was down to just 12 animals, the bison is today more than 2,000 strong in the wild, and it thrives in several European countries. Like the Sumatran rhino, it is a rare survivor of the Pleistocene, having avoided the fate of mammoths and cave bears. The Arabian oryx is now more than 1,000 strong, and it has been reintroduced into the wild in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Jordan and Israel.

Payne believes the best chance to save the Sumatran rhino now would be “one program, managed by experts” with the goal to “boost births by any and all means possible.”

“What gives me hope now is that … people are realizing ‘Oh my gosh, we have this window of time that’s going to be a make-or-break window,’” says Ellis. This year, she adds, she has seen increased attention and funding for the species.

Thus nothing brings on unbridled celebration more than the birth of a healthy calf.

At the srs, all eyes remain on not-so-little-anymore Delilah, who turned two this May. She is healthy, playful and, according to Arsan, more independent than her older brother.

“Delilah loves to be touched and rubbed, and she knows and trusts us who care for her daily,” he says.

She is spending less and less time with her mother, and soon they will part—just as they do in the wild. And in about four years, when she’s ready, Arsan hopes she can bear children.

Her name, Delilah, was chosen by Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo. In Javanese, the name means “God’s blessing.” It’s an aptly optimistic choice for one shouldering hopes from both her own 20-million-year-old species as well a much younger fellow mammal—from among which a few individuals are dedicating their working lives to her songs and those of her future kin.

You may also be interested in...

Can Fig Trees Help Us Adapt to a Changing Climate?

Science & Nature

Tunisia, where figs are one of the signature crops, has been an integral part of a just-concluded Mediterranean research project, FIGGEN, to assess how the trees thrive while climate changes are causing other crops to fail. For nearly four years scientists have worked to identify specific genetic traits that enable figs’ resilience and which varieties cope best with heat and drought. When FIGGEN publishes the results, farmers concerned for their future livelihoods may choose to grow the most promising types. Additionally, the study aims to plant a seed for preserving the biodiversity of increasingly arid ecosystems.

The American Hands Weaving Legacies From Saffron Threads

Science & Nature

Meet the keepers of US-grown saffron—a spice prized around the world—who have cultivated it as a culturally important ingredient for generations.

Saudi Arabia's Mustatils: Mysterious Monuments of the Desert

History

Science & Nature

In northwest Saudi Arabia, scattered across an area twice the size of Portugal, archeolog|sts and aerial surveyors have identified more than 1,000 roughly built, low, rectangular stone structures that date back 7,000 years to an era when today's deserts were savannas. These mustatils-"rectangle" in Arabic-have been long-known to regional tribes, and in 2018 archeologists began to investigate and excavate. Discoveries of animal bones and horns point toward ritual purposes. The great number of mustatils may be evidence of population and social organization. But why are there so many-and in so many different places? While no two are quite the same in length and width, all are close in height and shape. Amid more questions than clues, archeologists continue to dig.