Streaming Ramadan TV to the World

New platforms, new stories and more subtitles are making the comedies, thrillers, biopics and dramas of what has long been TV’s peak season in Muslim majority countries into a year-round, binge-ready global window on popular cultures.

Fatima al-Masri, a sales consultant in her 20s, grew up watching TV drama serials during Ramadan as a family tradition in Amman, Jordan. “We will be talking about it for hours, for days even,” she says. “You have no idea how much time we spend watching these shows, analyzing them. It opens up a lot of conversation.”

For nearly 2 billion people worldwide, the holy month of Ramadan is not just 29 or 30 days of fasting from dawn to sunset, prayer and charity. It is also a month of social gatherings and cultural events—including television dramas produced for the season. As travel and public health restrictions have hampered in-person socializing during Ramadan both in 2020 and this year, social media and television have been playing greater roles than ever.

Now along with searching YouTube for advice on how best to fast or what to make for the day’s fast-breaking iftar, observing Ramadan also involves deciding among apps such as Ramadan Diet, Daily Dua or dozens more. It means picking out Ramadan-themed gifs to share on Whatsapp threads. And it means selecting which TV series to binge with the family—and the options are overwhelming. Traditional Ramadan programming powerhouses like Egypt and Turkey as well as ones in Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Syria, Algeria and the UAE are all serving up ever-more sumptuous buffets of social dramas, cooking shows, music specials, comedies and religious programming.

Often described by Arab media experts as a sweeps season for the Middle East, Ramadan boosts TV viewership by up to 45 percent on traditional platforms, and YouTube has recently seen three-fold to four-fold Ramadan spikes. This is why Arabic-language networks so often premiere their top shows in Ramadan—from perennially popular prank shows like Ramez to cooking shows with popular Moroccan chef Assia Othman to Al Namous, a Kuwaiti drama featuring stories across social classes set in the 1940s and 1970s, and dozens more.

While satellite channels have delivered programs like these to millions of Arabic speakers for decades, streaming platforms like Netflix and YouTube are now bringing even more to new audiences, particularly in Europe, North America and Asia, with subtitling in major world languages.

Along with widened distribution and added viewership, streaming platforms and competitive programming are pushing producers to offer increasingly contemporary storylines and series shorter than a month’s worth of 30 episodes. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, Ramadan TV has offered a window on places viewers couldn’t travel to and also offered cultural insights.

“If you want to understand the region, you have to see it through its pop culture,” says Egyptian film critic Joseph Fahim. “A good way to start learning is through a show.”

“If you want to understand the region, you have to see it through its pop culture.”

—Joseph Fahim, film critic

Ramadan TV’s roots reach deep into centuries of Arabic oral story and poetic traditions. One of the most colorful figures of these traditions is that of the hakawati, or storyteller, who provided both entertainment and cultural continuity in streets, coffee shops, homes and salons mainly across the Middle East and North Africa. Hakawatis regaled crowds with romance and heroism, tragedy and comedy, often telling and retelling favorite stories. Many of the stories were serialized and contained moral nuggets embedded in their adventure or mirth—much like Ramadan TV today.

Although hakawatis—again like television—performed year round, they were particularly prized during Ramadan. During the holy month, they would prepare “a sumptuous repertoire of after-iftar tales to delight residents and visitors alike,” as Dubai-based Gulf News writer Sharmila Dhal put it, often competing with one another for pride and payment.

Today’s annual feast of drama and delight may take place around a high-definition screen, but it remains robust—as do revenues. According to Paris-based ratings company IPSOS, ad spending on TV during Ramadan has increased annually by about 12 percent. From Amman to Beirut, Casablanca, Dubai and beyond, streets and rooftops are plastered with massive ads touting the big-budget shows that rely on high viewership to be profitable.

In Amman, while al-Masri’s family prefers socially driven cheekiness like the Jordanian sketch comedy Bath Bayakha, the most popular Ramadan genre worldwide is the social-drama serial. In these the biggest stars often attract social media followers by the tens of millions. Al-Masri says that even when she doesn’t like the premise of a show, she still might watch it for the actors. “If the main character is played by a big name—like Taim Hasan or Yasmin Abdulaziz—that’s a huge factor,” she says.

In the past, al-Masri explains that she had to wait a whole year for new programs to be launched during Ramadan. But that is changing.

Heba Korayem, an independent marketing consultant in the UAE, says that until about five years ago, the Arabic TV industry was based on big production houses putting together shows that made a splash on pay TV before being sent to free TV and later ending up on YouTube for residual revenues.

“That lasted until around 2016,” she says, when streaming platforms like Sling TV, Netflix and others began to appear in the region.

“What was bad news for pay-TV networks became good news for the regional production houses,” says Korayem. “It meant new commissioning opportunities and new money.”

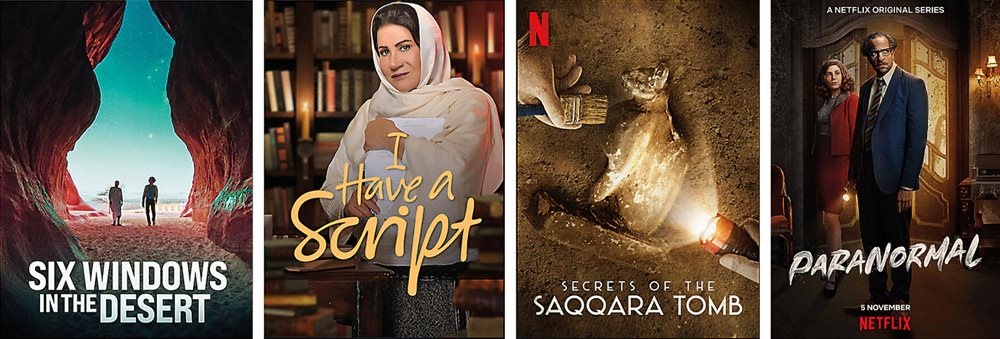

Korayem points out that it was actually in 2014 that Dubai-based ICFlix inaugurated original content in Gulf-region streaming with a social drama, HIV, and a police thriller, Al Makida, both from Egypt and both accompanied by subtitles in English and French. In 2017, with the Emirati series Qalb Al Adala (literally “heart of justice,” but in English the series’s title is Justice), Netflix began stepping in with investments in what she praises as “a diverse range of titles representing some of the best content from the Arab world,” all with subtitles in multiple languages. This year Netflix launched a documentary series, Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb; comedy series Drama Queen, starring satirical Egyptian puppet character Abla Fahita; as well as Jordanian producer, director, writer and comedy actress Tima Shomali’s Al Rawabi School for Girls, which features an all-female cast and crew.

More competition in the industry has sparked new creativity.

Netflix now also hosts a global library of recent Ramadan hits, from the Syrian Lebanese drama Al Hayba to the Egyptian period remake Secret of the Nile, which enjoyed massive success upon its release during Ramadan 2016.

Netflix also announced this year a multipicture partnership with the Riyadh-based Saudi studio Telfaz11, which first became famous a decade ago for homegrown comedy sketches on YouTube. The goal, says Nuha Eltayeb, Netflix’s director of content acquisitions for the Middle East, North Africa and Turkey, is to produce eight new feature films “showcasing the beauty of Saudi storytelling that will resonate with both Arab and global audiences.”

Korayem says the investments streaming platforms are making represent the biggest change since 1997, when satellite TV became widely available. More competition in the industry has sparked new creativity and made shows produced originally in Arabic more accessible worldwide. “You can be a lot more creative with streaming platforms,” she says. “The Arab media industry is experimenting.”

That’s a good thing, says critic Fahim, who welcomes the stimulus to upgrade from flash to substance and “push things beyond patriotic thrillers or stolid social dramas.” Many of the series to date, he says, “are not particularly good. And the ones that are really good usually don’t have bigger audiences.”

Fahim notes that streaming affects more than just content. It is changing its structure, “from storylines to stars, even the length of a series,” he says, “experimenting with shorter series, more bingeable content whose life isn’t restricted to Ramadan.”

Ramadan may remain “the core prize,” he says, “but streaming services are messing up the whole concept of Ramadan TV.”

Korayem credits Jamal Sannan, founder and CEO of Lebanon-based Eagle Films, with what she senses has become the new normal: “The whole year has become Ramadan season.”

Prominent among the new global audiences are Western viewers interested in Arabic language and Muslim-world cultures. Hannah Forster, a teacher of Arabic in Germany, observes that “there’s no other way you’re going to learn about Arab media and culture in such an authentic way without going there yourself.” And that, for the time being, isn’t yet possible for people without family or business relationships.

Watching Ramadan shows as a non-Muslim Westerner, she says, “confronts you with things you didn’t know about. It’s an educational activity and a challenge.” That’s why she has encouraged her high school and university students to watch as much as they can and take advantage of the subtitles as needed. “These Ramadan shows are authentic materials that convey important sociocultural and political content to students, straight from the source.”

“It’s OK to watch these shows for enjoyment, but you need to have a critical perspective as well.”

—Rebecca Joubin, professor

Julie Williams, who lives in Michigan, USA, is a newcomer to Ramadan TV, one for whom it’s a way to get more acquainted with the extended Middle Eastern family of her daughter’s husband. She says she started watching Secret of the Nile and a few others with English subtitles during the COVID-19 pandemic. The serial drama, lavish costumes and over-the-top plots were more fun than she anticipated. “I was expecting a documentary,” she says. “I was surprised to not see anything about Ramadan or Muslims. It showed me there are lots of different ways Muslims believe and think and act.”

She knows too that, at the same time, viewers need to be careful about what they take seriously and what they don’t. “It would be as if people in other countries thought the US was just like Keeping up with the Kardashians or Law & Order,” she says.

That kind of discretion is vital, says Rebecca Joubin, who is a professor of Arab studies at Davidson College in North Carolina, USA.

As an Arab American, she reflects that on one hand she is happy to see Ramadan TV open new windows into the Arab world for viewers in the West. But on the other hand, she finds herself at times frustrated. “I watch something and think, ‘Ugh, this is what represents us?’ Viewers have to realize that people on the ground are going to have mixed feelings about these series.”

She points to Netflix’s 2019 supernatural series Jinn, which courted controversy for its portrayal of youth culture in Jordan.

“We have to contextualize these programs and dig deeper,” says Joubin. “How are things being represented? Is this being written for a Western audience or an Arab audience? Is what we watch an authentic representation of Arab culture?”

“It’s okay to watch these shows for enjoyment, but you need to have a critical perspective as well,” she continues. “Stop for a moment and reflect on your stereotypes, realize that what makes it to the West will not always be representative of another part of the world—in part because it made it to the West.”

Viewed this way, the expanding vistas through the windows of Ramadan TV are also “a kind of mirror” to the shows’ own audiences, as each show is produced with certain expectations about viewers and what the producers expect will be their preferences. In viewing, she says, “we are also learning more about who we are and what we think about the world.”

You may also be interested in...

How Gulf's New Museums Are Championing Cultural Memory and Heritage

Arts

The result of decades of planning, new facilities in Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arabian Gulf reflect the region's cultural renaissance and effort to preserve its heritage.

Al Sadu Textile Tradition Weaves Stories of Culture and Identity

Arts

Across the Arabian Gulf, the traditional weaving craft records social heritage.

Restoration Uncovers Beauty of Georgia’s Hidden Wooden Mosques

Arts

Until recently few outsiders knew the wooden mosques dotting the highlands of Georgia existed, leaving many of them to deteriorate. The rediscovery of the architectural gems has sparked a movement for their preservation.