Is the Sky the Limit for The Gambia's Groundnuts?

From co-op farms and export-driven factories to market stalls run by young entrepreneurs, continental Africa's smallest country is adapting its globally popular crop of groundnuts peanuts to changing climate, changing markets and rising aspirations.

A late-morning sun shimmers off the broad mouth of the Gambia River as Tamsir Saho fishes into the pocket of his kaftan for his second phone. He takes the call from atop the ferry between Banjul, capital of The Gambia, and the semirural port of Barra on the north bank. A tall chap, Saho, 53, has built a thriving business in groundnuts—peanuts—the crop grown on a third of the country’s arable land, and which sustains livelihoods for roughly half a million people, or a quarter of Gambia’s population.

On the line, Saho breaks into a mix of some his country’s nearly two dozen languages. Switching among Wolof, Serer and Sengembaian Fula, and peppering in Anglo-French phrases like “soixante kilos top quality,” he is both a skilled linguist and a testament to the diversity within Gambia, smallest of the 48 countries of mainland Africa.

When he ends his call, he doesn’t look up but glances over to his other phone’s weather app. “In the growing season, I check it each morning before I check messages from my wife,” Saho says as the ferry chugs past cargo ships clustered in the waterway. Some of them, he points out, will carry groundnuts abroad, including his own, which he mainly sells to buyers in South and Southeast Asia.

Growing up on a farm with his father and grandfather informed Saho about groundnut cultivation, he says, and now he oversees three of the nine largest groundnut processing plants in Gambia.

It is mainly to the north and east of Barra that the Atlantic monsoon has long poured some 800 millimeters of rain every summer—more than London sees in a year. When the rains come, they transform sere bronze uplands over some 40 to 50 days into an emerald carpet. Varieties of peas and beans flower, nourishing seedpods underground.

But changing weather patterns are forcing adaptations and inspiring innovations. Modou Touray, who leads the agribusiness component of the nationwide Youth Empowerment Project (YEP), backed by the European Union in an effort to safeguard Gambia’s agricultural future, has been observing the changes and assessing challenges facing the groundnut industry.

“What we are seeing is changes in rainfall … along with increased pollution,” says Touray from his office at the International Trade Centre in Bakau, just west of Banjul. “This has affected groundnuts more than other agricultural sectors because they have a minimum amount of rainfall to make the crop viable.”

The monsoons, he explains, are “not always distributed evenly. … Sometimes half of it might fall in a few days,” rather than across the entire five-month growing season.

Records kept by the World Bank Group back up his observations. According to the international financial nonprofit, rainfall has decreased at a monthly rate of 8.8 millimeters since 1960, compounded by a temperature increase over the period of 1-degree-Celsius. As a result, crop yields are lower than they were in the 1960s and 1970s, and farming has been losing allure among the young since the 1990s.

“In those days we had a lot of groundnuts, because the rain came when we liked it,” says Malik, a resolute farmer in his 60s who offers only his first name as he unloads a shipment of groundnuts at a depot in Barra. The city is amid the heartland of tribes that migrated centuries ago westward from Sudan, and who help give Gambia its cultural and historical diversity. The five-month rainy season from June to October peaks in August, after which collected rainwater nourishes groundnuts as well as other major crops like mangoes and cashews. Malik echoes Touray’s concern. “These days it rains, it stops for three weeks, then rains again,” he says.

Erratic rains mean seedlings can fail and even the mature seed pods can yield smaller peanuts. This means less income to the farming family, which in a good year can live sustainably on the crop yields. Hunching down to speak, Malik ponders whether his own children and grandchildren will follow him into the groundnut fields. “Groundnuts have always been The Gambia’s number one crop,” but a litany of problems loom now. “We don’t have the equipment. … There’s no space now. ... It’s expensive,” he says, letting his voice trail off.

Musa Loum, 45, manager of the Barra depot of the Gambia Groundnut Corporation, voices similar concerns. The exodus of young Gambians from farms on the north side of the river to the more urbanized south side have disrupted life as the country once knew it.

“Every child in The Gambia learns that we depend upon groundnuts,” he says, patrolling his depot in a T-shirt and and jeans. “You find only young people there ... young people are going to the city.” Loum points toward the river’s south side, noting the country’s median age of 18.

That’s about the age that the urban centers of Gambia can seem designed to appeal to directly. There’s hustle, it seems, on every corner—a kind of energetic medley of voices and noises that would attract any 18-year-old. Billboard advertising on the highway to Gambia’s southern areas tempt with more idealized urban lures: “Saya Condensed Milk—More Protein For More Strength;” “Qcell—20Mbs For The Price Of 13Mbs.”

More than this, however, the urban south offers job opportunities. Many people on commuter buses carry a trade: wheelbarrow parts, biscuits, bags of pre-peeled oranges, shelled coconuts, fishing rods, drinking water in small plastic bags and hats to guard against the sun.

This rural-to-urban movement has increased since the 1990s. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs reports that 17 percent of Gambian migrants from the north to the south made the move in the 1990s. That percentage increased to 28 percent the next decade and, since 2010, the percentage of urban residents has increased at an annual rate of just above 4 percent.

Dressed in a blue suit and exuding the calm authority of a master of his subject, Touray sees incentives in the groundnut industry that can retain the young, talented and enterprising. Like Saho and Malik, Touray grew up in the groundnut-growing areas north of the Gambia River. “There were a lot of young people risking their lives to get to Europe by crossing the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea,” Touray says. “We took a market-led approach to the economic root causes of irregular migration,” and, he continues, “As agribusiness is the main driver of Gambian employment, with groundnuts as the key subsector, we saw the greatest potential for jobs and income for young people here.”

Since 2017, YEP has concentrated on vocational training and the creation of export opportunities for small businesses and job opportunities for young adults. “We have trained more than 5,000 young people and purchased over 100 groundnut machines,” he says, including roasters and peanut-paste presses. The government has also introduced new groundnut varieties, like brocous, which can be harvested in just 100 days, and offers improved resilience in shorter, less predictable rainy seasons.

New groundnut varieties can be harvested in just 100 days and offer improved resilience in shorter, less predictable rainy seasons.

Touray also sees youngsters keen to introduce contemporary tech into groundnut farming and processing. YEP has funded training on the installation and repair of photovoltaic solar panels that can power irrigation systems, borehole irrigation maintenance that can increase water retention amid irregular rains, and microgardening to produce extra food and income—again as a buffer against the increasingly higher risks associated with small-hold farming. Independent research showing YEP has created more than 1,000 jobs from its agribusiness support exceeds Touray’s own original forecast of 600 jobs. “We have doubled our targets,” Touray says with a smile. “That means we have the potential to create more.”

“Every child in Gambia learns that we depend upon groundnuts.”

—Musa Loum

Innovation also seems to permeate the independent, small-business commerce in Brikama Market, which sprawls over 4 square kilometers about an hour and a half’s drive south of Banjul. Here are hundreds of stalls selling groundnuts big, small, pulped, powdered, milled into flour and more. Tech here most noticeably takes the form of new roasting machines that spin automatically and roast a 60-kilogram bag of peanuts in half an hour—turning a cash crop into a value-added food commodity.

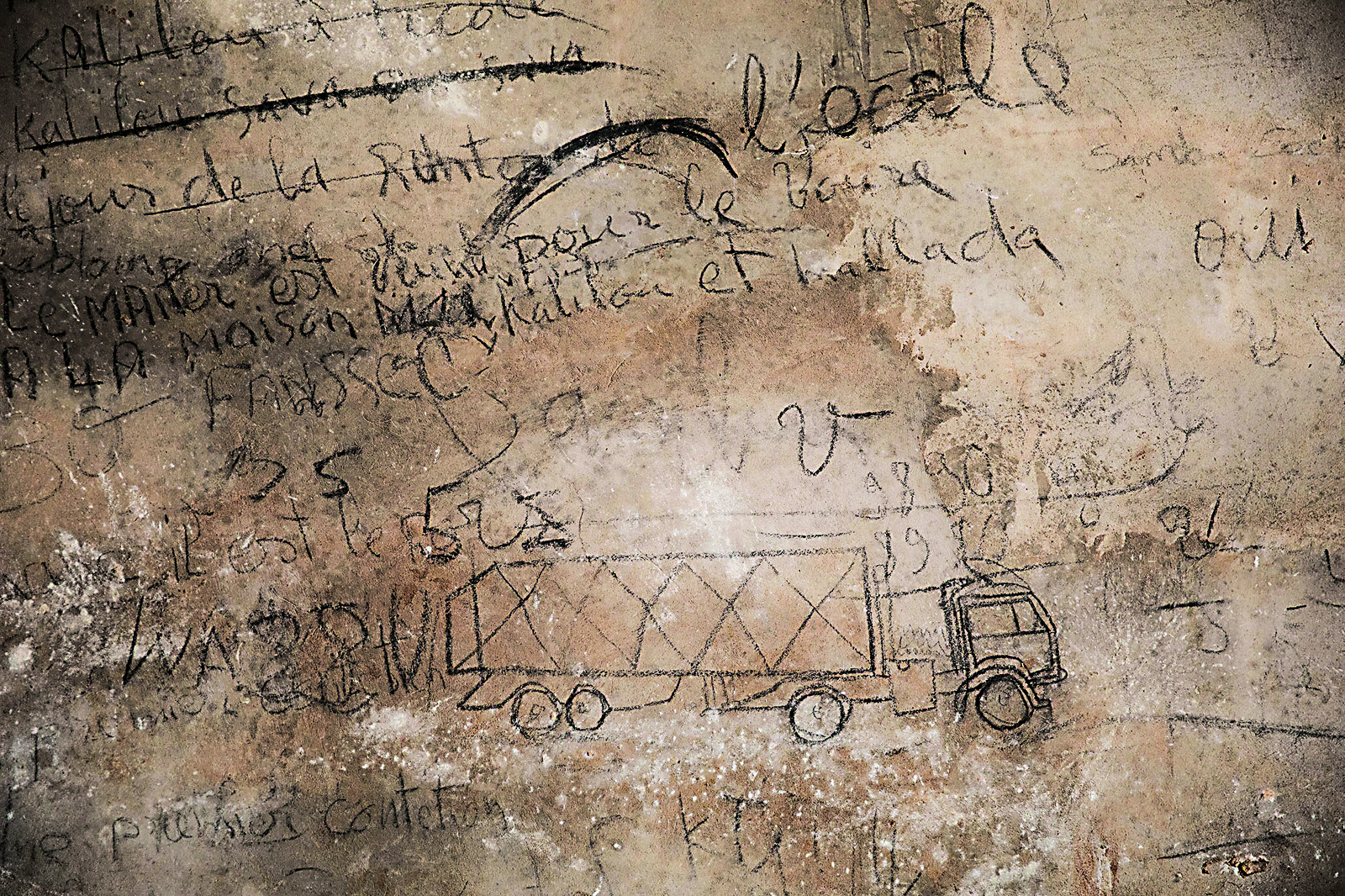

Nearby sit the smokey precursors of the automatic machines. Over a fire of tree stumps, workers labor to roast about 10 kilograms of groundnuts in a metal bowl that must be continuously turned by hand. The new groundnut roasting machines have become especially appealing as they can be fixed locally—and creatively: One machine is running thanks to a motorbike chain that has replaced a worn-out rubber belt.

Not far north of the market, adding value to groundnuts is the theme of agricultural stalls at the annual Trade Fair Gambia International. Some 500 exhibitors showcase goods from textiles to handicrafts at dusk, backed by a DJ and a dozen food kiosks.

Among those set up to sell is Favourite Foods, founded by 19-year-old marketeer Kumba Jobe. She has slickly packaged Gambian snacks like groundnut-coco, a savory mix spiced with nutmeg, coconut and ginger. Each Favourite Foods package lists the nutritional benefits for a young, aspirational audience: antioxidants, potassium, calcium. Jobe’s products include churagerrtah, a ready-made mix of pounded peanuts and rice, together with cooking instructions to turn it into a delicious porridge—perfect for the busy, 21st-century urban customer.

Also marketing her products at the trade fair is Ceesay. Twenty years old, she hopes to take Gambia’s beloved legume to value-added success by marketing her own Adama’s Processing Center groundnut oils and peanut butters. The packaging is splashed with aspirational adjectives like “pure” and “unrefined.” She produces both in the nearby Serekunda district using an oil press and a paste-making machine.

Overseas customers are looking for one thing—“quality,” asserts Ceesay. “I know the person who farmed the groundnuts I use.” This also means she can undercut her competition by purchasing her raw material for a lower price. “I sell my [largest] product at 1,750 Dalasi [about $32] compared to the imported oil, which costs about 2,100 Dalasi.”

Ceesay has her eyes set on markets beyond Gambia. “I sell them on Facebook, but I need help to sell more online,” she says.

Back on the banks of the Gambia River, Saho’s day of making rounds of groundnut processors in Barra is nearly done. Heading back to Banjul on the ferry, he again scrolls through his newer smartphone—this time for WeChat. Saho is ready to ship another container of groundnuts to China, where they will most likely end up as groundnut oil, as that industry gobbles fully two-thirds of the world’s total groundnut harvest. Shipping costs, however, have nearly doubled since the COVID-19 pandemic. A container from West Africa to China that cost $2,500 two years ago has spiked to $4,000, resulting in tough negotiations over WeChat.

But none of this seems to much trouble Saho’s ambitions. As the ferry ride comes to an end, Saho positions himself to be one of the first off. He’ll be back again tomorrow.

About the Author

Samantha Reinders

Samantha Reinders (samreinders.com; @samreinders) is an award-winning photographer, book editor, multimedia producer and workshop leader based in Cape Town, South Africa. She holds a master’s degree in visual communication from Ohio University, and her work has been published in Time, Vogue, The New York Times and more.

Tristan Rutherford

Tristan Rutherford is a 7-time award-winning journalist. His writing appears in The Sunday Times and the Atlantic.

You may also be interested in...

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper..jpg?cx=0.36&cy=0.38&cw=480&ch=360)

From Shimla to Chittagong: How a Fish Dish Helped Me Remember

Food

A writer prepares cookbook author-restaurateur Asma Khan’s recipe for Shimla Mirch Machli in her London kitchen—and is transported to the places of her grandparents’ birth.

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.