The Islamic Roots of the Modern Hospital

By the mid-ninth century, more than 30 bimaristans—centers for treating illness and injury—were working from the Arab Middle East to Persia in the east and Al-Andalus in the west. Dedicated to the empirical pursuit of wellness, their design, organization and goals were much the same as those of hospitals today.

The hospital shall keep all patients, men and women, until they are completely recovered. All costs are to be borne by the hospital whether the people come from afar or near, whether they are residents or foreigners, strong or weak, low or high, rich or poor, employed or unemployed, blind or signed, physically or mentally ill, learned or illiterate. There are no conditions of consideration and payment; none is objected to or even indirectly hinted at for non-payment. The entire service is through the magnificence of God, the generous one.

—policy statement of the bimaristan of al-Mansur Qalawun in Cairo, c. 1284 ce

The modern West’s approach to health and medicine owes countless debts to the ancient past: Babylon, Egypt, Greece, Rome and India, to name a few. The hospital is an invention that was both medical and social, and today it is an institution we take for granted, hoping rarely to need it but grateful for it when we do. Almost anywhere in the world now, we expect a hospital to be a place where we can receive ease from pain and help for healing in times of illness or accidents.

We can do that because of the systematic approach—both scientifically and socially—to health care that developed in medieval Islamic societies. A long line of caliphs, sultans, scholars and medical practitioners took ancient knowledge and time-honored practices from diverse traditions and melded them with their original research to feed centuries of intellectual achievement and drive a continual quest for improvement. Their bimaristan, or asylum of the sick, was not only the true forerunner of the modern hospital, but also virtually indistinguishable from the modern multi-service healthcare and medical education center.

The bimaristan served variously as a center of treatment, a convalescent home for those recovering from illness or accident, a psychological asylum and a retirement home that gave basic maintenance to the aged and infirm who lacked a family to care for them.

Asylum of the Sick

The bimaristan was but one important result of the great deal of energy and thought medieval Islamic civilizations put into developing the medical arts. Attached to the larger hospitals—then as now—were medical schools and libraries where senior physicians taught students how to apply their growing knowledge directly with patients. Hospitals set examinations for the students and issued diplomas. The institutional bimaristans were devoted to the promotion of health, the curing of diseases and the expansion and dissemination of medical knowledge.

The Nur al-Din Bimaristan, a hospital and medical school in Damascus, was founded in the 12th century. Today it is the Museum of Medicine and Science in the Arab World.

The First Hospitals

Although places for ill persons have existed since antiquity, most were simple, without more than a rudimentary organization and care structure. Incremental improvements continued through the Hellenistic period, but these facilities would barely be recognizable as little more than holding locations for the sick. In early medieval Europe, the dominant philosophical belief held that the origin of illness was supernatural and thus uncontrollable by human intervention: As a result, hospitals were little more than hospices where patients were tended by monks who strove to assure the salvation of the soul without much effort to cure the body.

Muslim physicians took a completely different approach. Guided by sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (hadith) like “God never inflicts a disease unless He makes a cure for it,” collected by Bukhari, and “God has sent down the disease and the cure, and He has appointed a cure for every disease, so treat yourselves medically,” collected by Abu al-Darda, they took as their goal the restoration of health by rational, empirical means.

Hospital design reflected this difference in approach. In the West, beds and spaces for the sick were laid out so that the patients could view the daily sacrament of the Mass. Plainly (if at all) decorated, they were often dim and, owing to both climate and architecture, often damp as well. In the Islamic cities, which largely benefited from drier, warmer climates, hospitals were set up to encourage the movement of light and air. This supported treatment according to humoralism, a system of medicine concerned with corporal rather than spiritual balance.

Mobile Dispensaries

The first known Islamic care center was set up in a tent by Rufaydah al-Aslamiyah during the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad. Famously, during the Ghazwah Khandaq (Battle of the Ditch), she treated the wounded in a separate tent erected for them.

Later rulers developed these forerunners of “mash” units into true traveling dispensaries, complete with medicines, food, drink, clothes, doctor and pharmacists. Their mission was to meet the needs of outlying communities that were far from the major cities and permanent medical facilities.

They also provided the rulers themselves with mobile care. By the early 12th-century reign of Seljuq Sultan Muhammad Saljuqi, the mobile hospital had become so extensive that it needed 40 camels to transport it.

Permanent Hospitals

The first Muslim hospital was only a leprosarium—an asylum for lepers—constructed in the early eighth century in Damascus under Umayyad Caliph Walid ibn ‘Abd al-Malik. Physicians appointed to it were compensated with large properties and munificent salaries. Patients were confined (leprosy was well known to be contagious), but like the blind, they were granted stipends that helped care for their families.

The earliest documented general hospital was built about a century later, in 805, in Baghdad, by the vizier to the caliph Harun al-Rashid. Few details are known, but the prominence as court physicians of members of the Bakhtishu’ family, former heads of the Persian medical academy at Jundishapur, suggests they played important roles in its development.

Over the following decades, 34 more hospitals sprang up throughout the Islamic world, and the number continued to grow each year. In Kairouan, in present-day Tunisia, a hospital was built in the ninth century, and others were established at Makkah and Madinah. Persia had several: One in the city of Rayy was headed for a time by its Baghdad-educated native son, Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi.

In the 10th century five more hospitals were built in Baghdad. The earliest was established in the late ninth century by ‘Al-Mu’tadid, who asked Al-Razi to oversee its construction and operations. To start, Al-Razi wanted to determine the most salubrious place in the city: He had pieces of fresh meat placed in various neighborhoods, and some time later, he checked to determine which had rotted the least and sited the hospital there. When it opened, it had 25 doctors, including oculists, surgeons and bonesetters. The numbers and specialties grew until 1258, when the Mongols destroyed Baghdad.

The vizier ‘Ali ibn Isa ibn Jarah ibn Thabit wrote in the early 10th century to the chief medical officer of Baghdad about another group:

I am very much worried about the prisoners. Their large numbers and the condition of prisons make it certain that there must be many ailing persons among them. Therefore, I am of the opinion that they must have their own doctors who should examine them every day and give them, where necessary, medicines and decoctions. Such doctors should visit all prisons and treat the sick prisoners there.

Shortly afterward a separate hospital was built for convicts, fully staffed and supplied.

This plaque on the wall of the Bimaristan Arghun in Aleppo, Syria, commemorates its founding by Emir Arghun al-Kamili in the mid-14th century. Care for mental illnesses here included abundant light, fresh air, running water and music.

In Egypt, the first hospital was built in 872 in the southwestern quarter of Fustat, now part of Old Cairo, by the ‘Abbasid governor of Egypt, Ahmad ibn Tulun. It is the first documented facility that provided care also for mental as well as general illnesses. In the 12th century, Saladin founded in Cairo the Nasiri hospital, which later was surpassed in size and importance by the Mansuri, completed in 1284. It remained the primary medical center in Cairo through the 15th century, and today, renamed Qalawun Hospital, it is used for ophthalmology.

In Damascus the Nuri hospital was the leading one from the time of its foundation in the mid-12th century well into the 15th century, by which time the city contained five additional hospitals.

In the Iberian Peninsula, Cordóba alone had 50 major hospitals. Some were exclusively for the military, and the doctors there supplemented the specialists who attended to the caliphs, military commanders and nobles.

With its airy, high-ceiling rooms, the Bimaristan Arghun functioned as a hospital until the early 20th century. Later, it became a museum.

Above and right: Fountains were central to the architecture of the Bimaristan Arghun: Three courtyards each held a fountain, around which patient rooms were arranged, while the central courtyard featured a large rectangular pool and well. (Since these photos were taken, unesco has listed the bimaristan as damaged by warfare.)

Organization

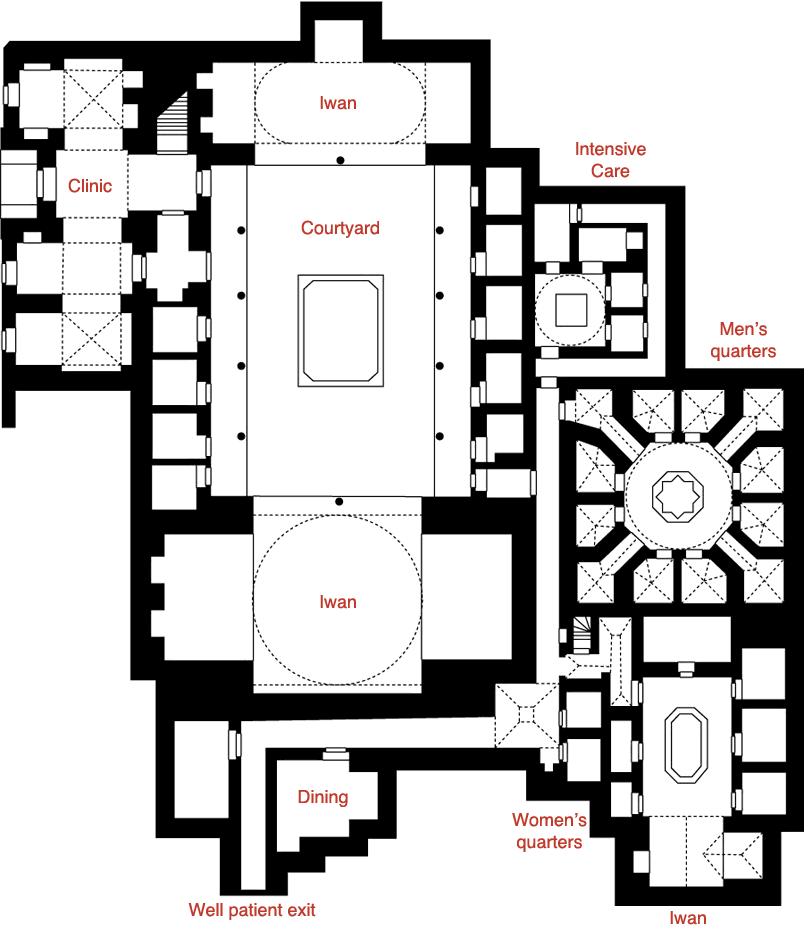

In a fashion that would still be recognizable today, the typical Islamic hospital was subdivided into departments such as systemic diseases, surgery, ophthalmology, orthopedics and mental diseases. The department of systemic diseases was roughly equivalent to today’s department of internal medicine, and it was usually further subdivided into sections dealing with fevers, digestive troubles, infections and more. Larger hospitals had more departments and diverse subspecialties, and every department had an officer-in-charge and a presiding officer in addition to a supervising specialist.

Hospitals were staffed also with a sanitary inspector who was responsible for assuring cleanliness and hygienic practices. In addition, there were accountants and other administrative staff to assure that hospital conditions—financial and otherwise—met standards. There was a superintendent, called a sa’ur, who was responsible for overseeing the management of the entire institution.

Physicians worked fixed hours, during which they saw the patients who came to their departments. Every hospital had its own staff of licensed pharmacists (saydalani) and nurses. Medical staff salaries were fixed by law, and compensation was distributed at a rate generous enough to attract the talented.

Funding for the Islamic hospitals came from the revenues of pious bequests called waqfs. Wealthy men and rulers donated property to existing or newly built bimaristans as endowments, and the revenues from the bequests paid for building and maintenance. To help make it pay, such revenues could come from any mix on the property of shops, mills, caravanserais or even entire villages. The income from an endowment would sometimes also cover a small stipend to the patient upon dismissal. Part of the state budget also went toward the maintenance of hospitals. To patients, the services of the hospital were free, though individual physicians occasionally charged fees.

Patient Care

Bimaristans were open to everyone on a 24-hour basis. Some only saw men while others, staffed by women physicians, saw only women; still others cared for both in separate wings with duplicate facilities and resources. To treat less serious cases, physicians staffed outpatient clinics and prescribed medicines to be taken at home.

Special measures were taken to prevent infection. Inpatients were issued hospital wear from a central supply area while their own clothes were kept in the hospital store. When taken to the hospital ward, patients would find beds with clean sheets and special stuffed mattresses ready. The hospital rooms and wards were neat and tidy with abundant running water and sunlight.

Inspectors evaluated the cleanliness of the hospital and the rooms on a daily basis. It was not unusual for local rulers to make personal visits to make sure patients were getting the best care.

The course of treatment prescribed by doctors began immediately upon arrival. Patients were placed on a fixed diet, depending on condition and disease. The food was of high quality and included chicken and other poultry, beef and lamb, and fresh fruits and vegetables.

The major criterion of recovery was that patients be able to ingest, at one time, an amount of bread normal to a healthy person, along with the roasted meat of a whole bird. If patients could easily digest it, they were considered recovered and subsequently released. Patients who were cured but too weak to discharge were transferred to the convalescent ward until they were strong enough to leave. Needy patients were given new clothes, along with a small sum to aid them in re-establishing their livelihood.

In Egypt, the al-Mansur Qalawun Complex in Cairo includes a hospital, school and mausoleum. It dates from 1284-85.

The 13th-century doctor and traveler ‘Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi, who also taught at Damascus, narrated an amusing story of a clever Persian youth who was so tempted by the excellent food and service of the Nuri hospital that he feigned illness. The doctor who examined him figured out what the young man was up to and admitted him nevertheless, providing the youth with fine food for three days. On the fourth day, the doctor went to his patient and said with a rueful smile, “Traditional Arab hospitality lasts for three days: Please go home now!”

The quality of care was subject to review and even arbitration, as related by Ibn al-Okhowa in his book ‘Ma’alem al-Qurba fi Talab al-Hisba’ (The Features of Relations in al-Hisba):

If the patient is cured, the physician is paid. If the patient dies, his parents go to the chief doctor; they present the prescriptions written by the physician. If the chief doctor judges that the physician has performed his job perfectly without negligence, he tells the parents that death was natural; if he judges otherwise, he tells them: Take the blood money of your relative from the physician; he killed him by his bad performance and negligence. In this honorable way, they were sure that medicine is practiced by experienced, well-trained persons.

In addition to the permanent hospitals, cities and major towns also had first aid and acute care centers. These were typically located at busy public places such as large mosques. Maqrizi described one in Cairo:

Ibn Tulun, when he built his world-famous mosque in Egypt, at one end of it there was a place for ablutions and a dispensary also as annexes. The dispensary was well equipped with medicines and attendants. On Fridays there used to be a doctor on duty there so that he might attend immediately to any casualties on the occasion of this mammoth gathering.

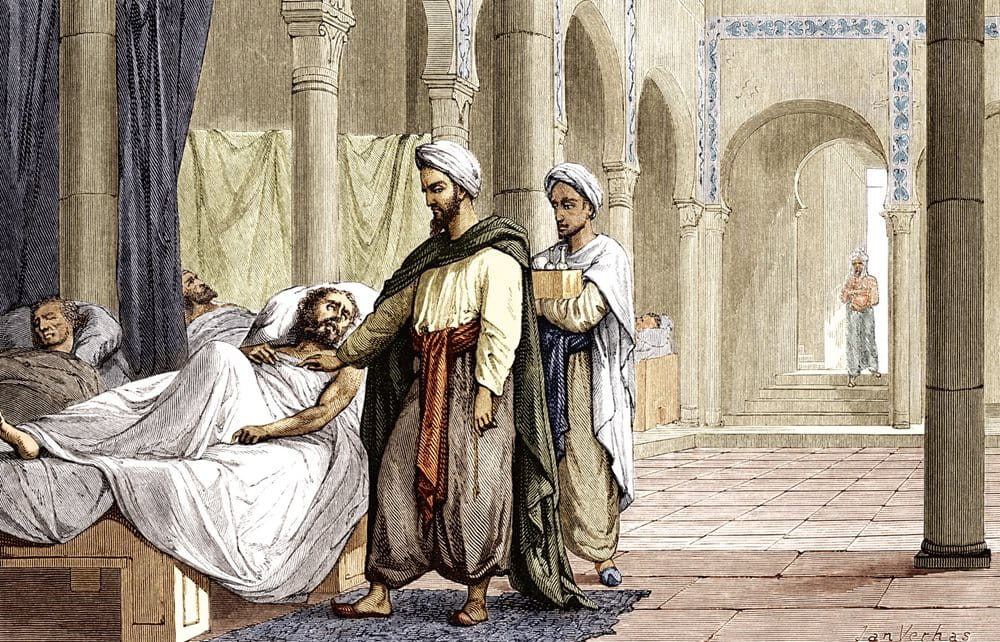

Depicting a scene in the hospital at Cordóba, then in Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), this 1883 illustration shows the famed physician Al-Zahrawi (called Abulcasis in the West) attending to a patient while his assistant carries a box of medicines.

Medical Schools & Libraries

Because one of the major roles of the hospitals was the training of physicians, each hospital had a large lecture theater where students, along with senior physicians and medical officers, would meet and discuss medical problems in seminar style. As training progressed, medical students would accompany senior physicians to the wards and participate in patient care—much like a modern residency program.

Surviving texts, such as those in Ibn Abi Usaybi’ah’s ‘Uyun al-anba’ fi tabaqat al-atibb’ (Sources of Information on Classes of Physicians), as well as student notes, reveal details of these early clinical rounds. There are instructions on diets and recipes for common treatments, including skin diseases, tumors and fevers. During rounds, students were told to examine the patients’ actions, excreta, and the nature and location of swelling and pain. Students were also instructed to note the color and feel of the skin, whether hot, cool, moist, dry or loose.

Training culminated in an examination for a license to practice medicine. Candidates had to appear before the region’s government-appointed chief medical officer. The first step required was to write a treatise on the subject in which the candidate wanted to obtain a certificate. The treatise could be an original piece of research or a commentary on existing texts, such as those of Hippocrates, Galen and, after the 11th century, Ibn Sina, and more.

Candidates were encouraged not only to study these earlier works, but also to scrutinize them for possible errors. This emphasis on empiricism and observation rather than slavish adherence to authorities was one of the key engines of the medieval Islamic intellectual ferment. Upon completion of the treatise, candidates were interviewed at length by the chief medical officer, who asked them questions relevant to problems of the prospective specialties. Satisfactory answers led to licensed practices.

Another key aspect to the hospital, and of critical importance to both students and teachers, was the presence of extensive medical libraries. By the 14th century, Egypt’s Ibn Tulun Hospital had a library comprising 100,000 books on various branches of medical science. This was at a time when Europe’s largest library, at the University of Paris, held 400 volumes.

Cradle of Islamic medicine and prototype for today’s hospitals, bimaristans count among numerous scientific and intellectual achievements of the medieval Islamic world. But of them all, when ill health or injury strikes, there is no legacy more meaningful.

You may also be interested in...

Pearls, Power and Prestige: The Symbolism Behind Byzantine Jewelry

Arts

History

A 1,500-year-old gem-encrusted Byzantine bracelet reveals more than just its own history; it symbolizes an empire’s narrative.

Voices That Shape Cross-Cultural Understanding

History

In its 75-year history, AramcoWorld has enlightened readers with stories about people throughout history and the modern world who have made an impact. Part 5 of our anniversary series examines the magazine’s positive portrayals of explorers, teachers, scientists and others to fulfill a mission of cultural bridge-building.

How Ancient Knowledge Shaped Modern Technology

History

Science & Nature

Part 3 of our series celebrating AramcoWorld’s 75th anniversary highlights the magazine’s emphasis on experts and institutions that push the boundaries of present-day knowledge while paying homage to historical figures and writings that paved their way.