The Extraordinary Ordinary #everyday

Founded by journalists to look beyond the headlines, Everyday Projects comprises more than 50 Instagram feeds featuring photography that captures a mosaic of life from just about everywhere, every day.

When picturing the Middle Eastern and Muslim worlds, it can be difficult to see beyond news images covering politics and crises. And yet, every day—literally—dedicated photojournalists, eager to tell the whole story of those lands, are doing just that on Instagram.

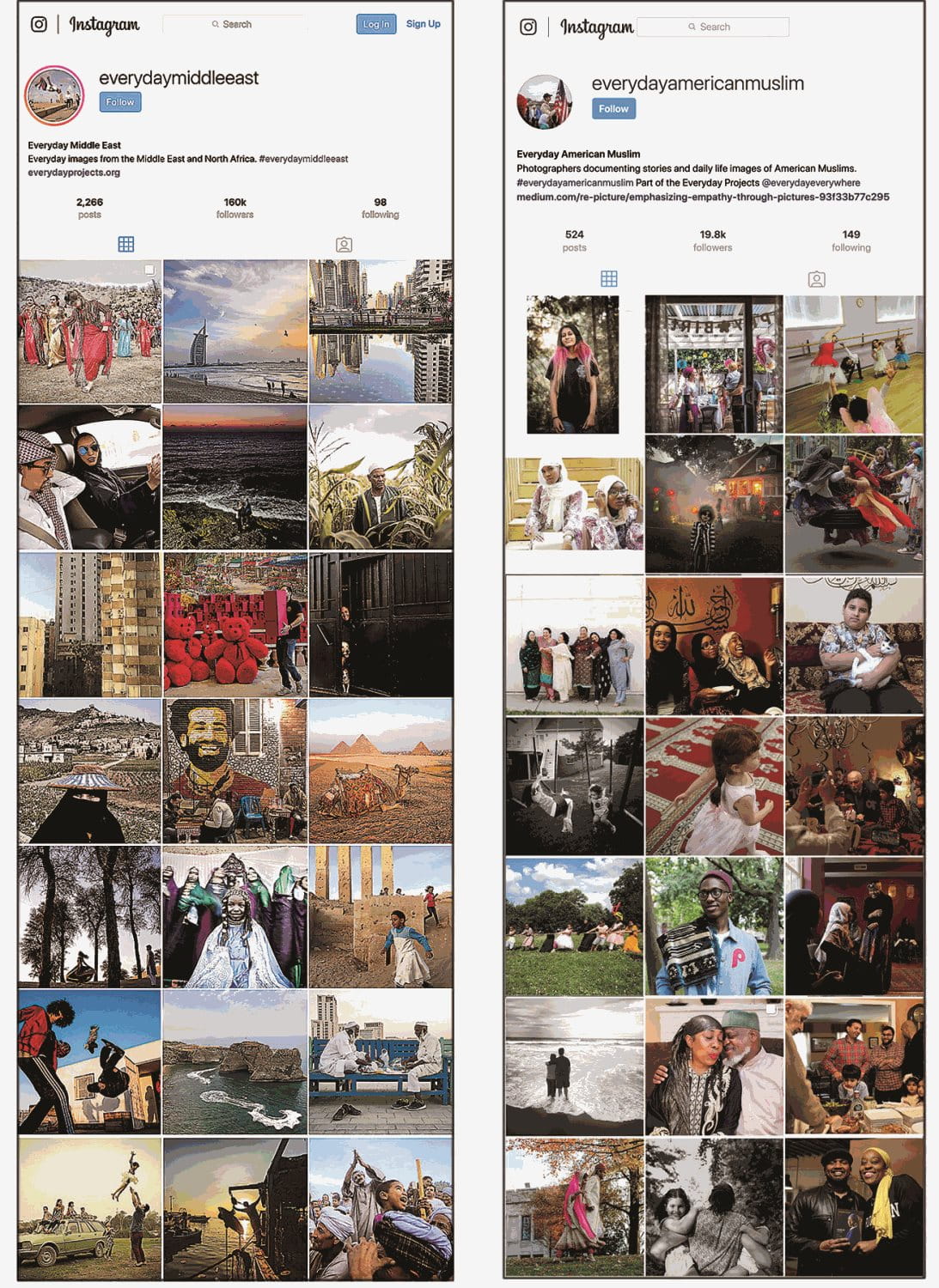

Through accounts like @everydaymiddleeast, @everydayafg (Everyday Afghanistan) and @everydayamericanmuslim, and scores of photographers are posting pictures and videos that capture moments that news stories simply don’t have room for—the day-to-day situations of life, be they joyous, harsh, traditional, provocative or just plain mundane. The images are extraordinary in that they capture the ordinary—like the photo of female university students in Iraq crowding a vendor to purchase schoolbooks; the shot of children flying through the air on the swings of a handmade carousel in Afghanistan; and the image of a family in Saudi Arabia sitting down to a holiday meal in their backyard.

The founders and curators of the feeds present day-to-day situations they envision will help break down stereotypes through images of relatable human situations. This, they hope, will diminish fear among cultures and promote mutual understanding.

Merrill, who was based in Cote d’Ivoire first as a journalist for The Associated Press and later as a volunteer with the Peace Corps, started the first Everyday account on Instagram, @everydayafrica, in 2012 with Peter DiCampo, then a freelance photojournalist based in Ghana, who had also served in the Peace Corps. Their aim, Merrill says, was to counterbalance the typical news stories from Africa—which they were also reporting—on war, famine and disease. “Those stories were important,” he says, “but we still felt like we were just piling on” to a crisis-oriented image of the continent.

Using iPhones, the pair began to document daily scenes around them and post their pictures through @everydayafrica. The account grew in popularity—it currently has 395,000 followers—and soon Everyday feeds began appearing from other places around the world.

So exciting that the pair began helping some of the other founders. In 2014 they worked with Instagram to bring the heads of several Everyday feeds to New York’s annual Photoville photography festival, where they exhibited images and, two days later, agreed to join forces.

“We started The Everyday Projects as a nonprofit because in bringing all of these like-minded communities together, we saw the potential to use photography to combat stereotypes and disrupt media-driven media clichés worldwide,” Merrill says.

The Everyday Projects is now an umbrella for 51 feeds from “Latin America

to Asia, Australia to the Middle East, Mumbai to the Bronx,” according to its website, as well as topic-based accounts that include @everydayclimatechange, @everydaymigration and @everydayextinction, The Everyday Projects has its own Instagram account, @everydayeverywhere, and it hosts a blog called Re-Picture. Merrill and DiCampo have started a curriculum for us secondary schools that teaches about visual literacy and how to debunk stereotypes internationally. No one is paid. Each of the feeds and accompanying activities is a project of passion.

At least 11 of the accounts focus on Middle Eastern lands or Muslim-majority

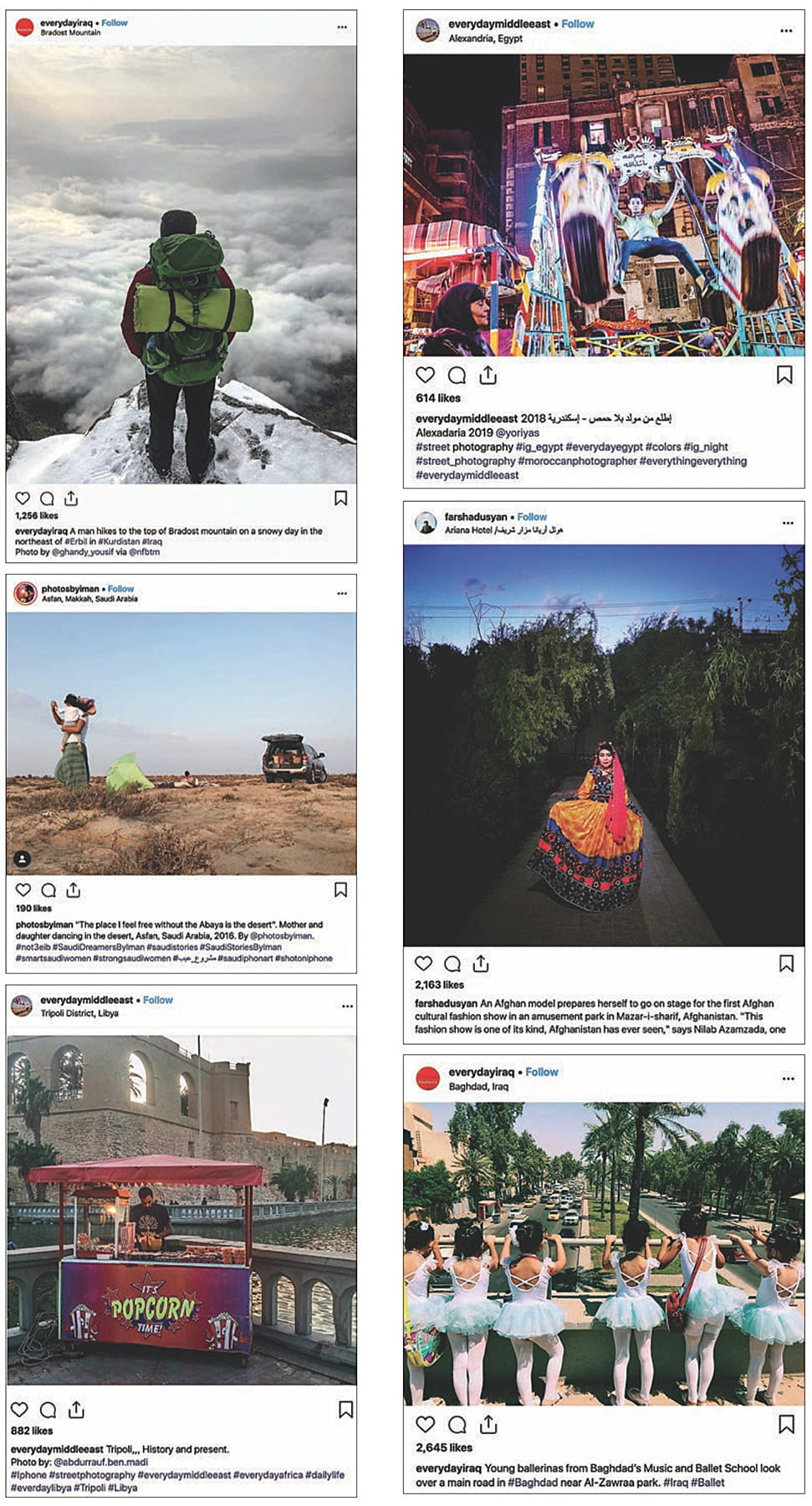

societies, and each has anywhere between 2,000 to 160,000 followers. True to the Everyday aim, the accounts feature barrages of universally relatable images, proving both commonalities and differences between cultures. Like the innocent love between a boy and his pet shown in an image from @everydaymiddleeast of a young Palestinian hugging his blue-collared white dog on a beach in the Gaza Strip. Or the picture on the same account of a vendor who has parked his bright red stand with English lettering announcing, “It’s Popcorn Time,” against an old fortress in Tripoli, Libya. Who knew popcorn was a street food in Libya? But then, who doesn’t love popcorn? Or the photo on @everydaypakistan featuring a father capturing a phone picture of his smiling son standing in the splashing surf of a beach in Pakistan.

For Afghan photojournalist Farshad Usyan, who photographs the hardest of news stories for Agence France-Presse, @everydayafg offers the freedom to document the human stories beyond the violent images typically expected from his homeland. News organizations are “focused on hard news. Sometimes even five deaths are not news for agencies. While in my work, every individual and every feeling matters,” says Usyan, a top contributor and curator of the feed since 2015.

A humanitarian activist, he uses the feed to cover daily struggles related to poverty, child labor, women’s rights and—because he also has medical training—health issues. He also documents changing social norms such as new fashion shows and teens socializing over a snooker game, and through @everydayclimatechange his images highlight climate-based threats to agriculture, Afghanistan’s main livelihood.

Meanwhile, Jiddah-based photojournalist Iman Al-Dabbagh has earned a name on @everydaymiddleeast for her intimate images from Saudi Arabia, especially of women. Her pictures bring viewers into homes, living rooms, feast-laden tables and backyards. She shows lighthearted pictures of little girls playing at a street festival, loving couples and mothers in sundresses cooing their babies. Her women are active: athletes stretching before a marathon; a group biking through Jiddah; a young woman riding a horse on a carousel, her young face framed by perfect brown curls.

“I wanted to show the world what I grew up with, as opposed to what’s in the media,” Al-Dabbagh says.

Zoshia Minto, a wedding photographer based in Maryland, launched @everydayamericamuslim in late 2016, after being inspired by @everydayrefugees (which is independent of The Everyday Projects) and the storytelling power of its photographs. Her hope is to similarly serve her American Muslim community. “I wanted to show everyday life of Muslims in America, just to balance what we see in the media, to offer a different perspective,” she says.

Jefferson Middle School Academy students pose with Everyday Projects cofounder Austin Merrill, at the opening of the exhibition “Everyday DC” at Pepco Edison Place Gallery in Washington, D.C. The students were among 150 who documented daily life in the District of Columbia in what is now a three-year-old annual educational and photographic event.

The account @everydayamericamuslim shows families on camping trips, at potluck parties, trick-or-treating and praying in mosques as their children play alongside. It also shows portraits of women as fashionistas, athletes, professors, rappers and entrepreneurs. One woman is a kickboxer: she sports a soft, pink headscarf and matching pink boxing gloves.

Minto says her hope “is that anyone looking at the images can find something in common in them.”

Finding similarities between cultures is exactly what Merrill and DiCampo were aiming for. Through so many day-to-day images, “we can celebrate the commonalities,” says Merrill. “It should make us understand each other.”

You may also be interested in...

A Quiet Path Through Recipes: A Conversation With Jeff Koehler

Arts

Culture

Jeff Koehler approaches food as a vessel for storytelling, for geography and cultural identity.

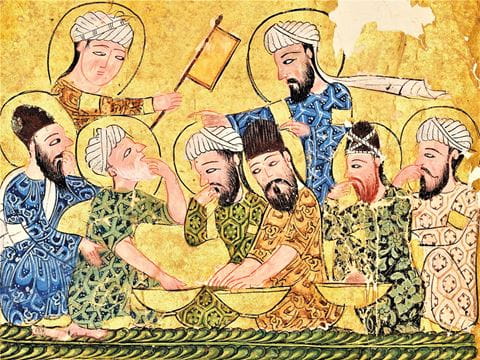

Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, a Conversation With Food Historian and Author Nawal Nasrallah

Arts

In Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, Arab food historian Nawal Nasrallah breathes new life into an anonymously compiled 13th-century cookbook.

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.