Cooling Dubai

Some 90 former warehouses have been transformed into a lively cultural scene at Alserkal Avenue—the latest of Dubai’s replies to the question, “What can art do for a city?”

It’s the kind of industrial neighborhood where you don’t expect to encounter a soul. Hulking steel-walled factories studded with air conditioning units, reinforced road surfaces built for heavy trucks, a maze of concrete and glass, all baking under the Dubai sun.

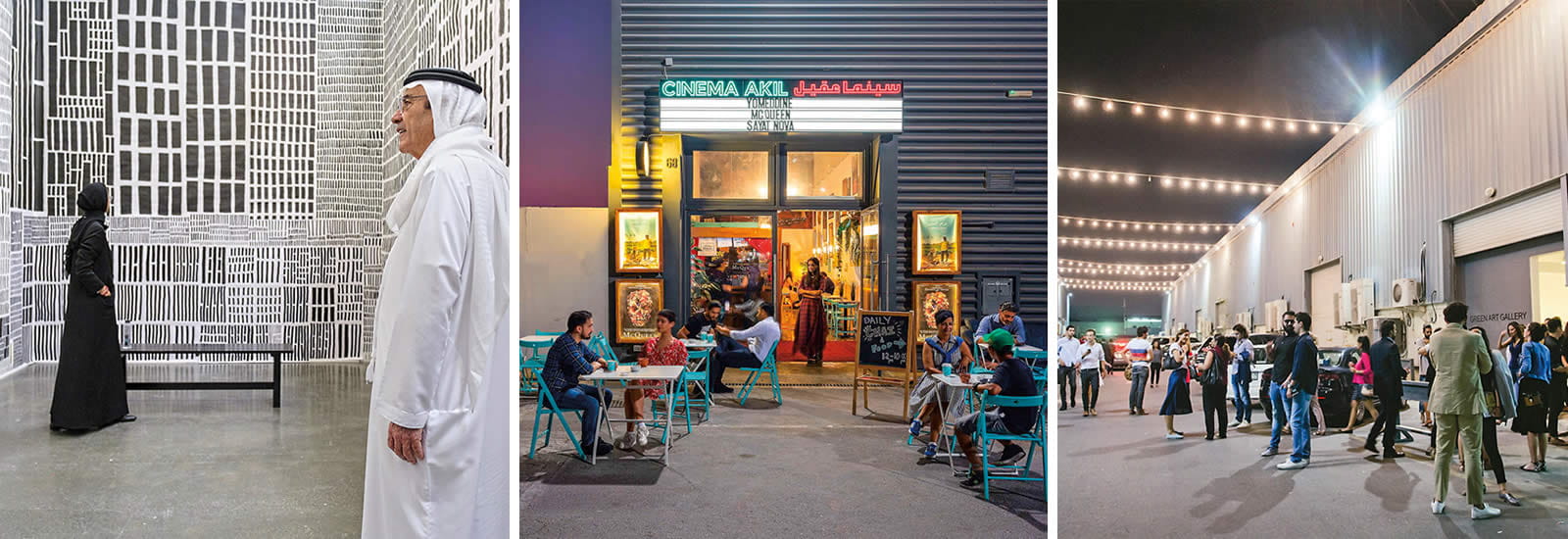

But Alserkal Avenue this morning is filled with life, and art.

Office workers eat lunch at an eclectic café whose chairs and tables are made from car tires and packing cases. In front of art gallery windows, young professionals browse for one-of-a-kind home decor. A family, mom and dad with kids in tow, exudes high excitement about a day out. They’re all here for what Alserkal Avenue brings to this city in the desert.

It’s especially lively because it’s spring, Dubai’s “art season,” which includes not only Alserkal Avenue’s Galleries Nights, but also the much more well-known Art Dubai festival, Art Nights at the Dubai International Financial Centre (difc), and the SIKKA Art Fair.

Green Art Gallery is one of the district’s most prominent venues. It was founded in 1987 in Syria and it has been part of Alserkal Avenue since 2011. It’s a white cube of space hidden behind a flat concrete facade.

“You’re building a scene from scratch,” says Green Art’s director Yasmin Atassi. It’s the task of building a sustainable art scene in a city not well known for art and culture, she adds. “Artists love to show in Dubai. It gives them access to art markets—contacts, shows, agents and more—over the whole of Asia.”

Alserkal Avenue is not, strictly speaking, a road: It is a labyrinth of narrow streets, a self-contained district. Its 90 warehouses offer a palette of mixed-use creative spaces, a dozen contemporary art galleries and 60 creative businesses, from architectural firms, chocolate makers, free coworking and nonprofit arts spaces to an independent cinema. All helped the Avenue attract 570,000 visitors last year.

But one does not just move in: Alserkal Avenue is itself a kind of grand, curated metagallery whose members have been selected.Many are enterprises that might struggle to take root amid the commercial rents of Dubai’s high-traffic shopping districts. Alserkal Avenue, however, is privately funded by Abdelmonem Bin Eisa Alserkal and the Alserkal family to create a self-sustaining community. Additionally, Alserkal Avenue offers grants, and it supports artists to publish and attend global art fairs.

“The support of Alserkal Avenue has been wonderful,” says Atassi. “They are very kind with support when we need it. They make everything possible to make sure we don’t have extra overhead.”

What do arts and culture bring to a city?

Street artist eL Seed, famous for his public “calligrafitti” art, is one of the Avenue’s most acclaimed residents. His studio, open since 2015, is far larger than what he could have in his former Parisian base. He keeps it open to the public for most of the year.

“Alserkal offered me a dream space,” he says. “The great advantage to be in a space like this is the fact that I am able to have such a large footprint.”

eL Seed’s artworks can be very large, building on his early days as a graffiti and street artist, combining the style and scale of spray-paint murals with the traditions of Arabic calligraphy to express messages of peace and unity.

“Throughout the year, I invite school children to come to my studio to experience what a day at the studio is like. It is important because when I was about 16 years old, an artist came to my school in Paris, and I was very influenced by him. I owe him for the inspiration,” he says.

Art pulled eL Seed out of the streets of 1980s Paris, away from a life that might have turned out very differently. Because his life was transformed by contact with art, eL Seed is using his Avenue studio to offer that to young people today—just as the Avenue does for the entire city. It’s a pattern of transformation, and it’s one that takes place in many cities across the globe, each in its own way.

First come artists and creative entrepreneurs, usually to low-rent, often formerly industrial areas. Along with the color and life of painting, dance, fashion and digital arts, they bring that elusive-but-essential quality that defies easy definition: the arts make the place cool.

Then things follow. Educated, high-skill people come to live in the cool places. They draw in businesses that want to hire top talent. Prosperity brings services, with more people. Arts and culture become the foundations for an economic ecosystem. The city becomes a better place to live.

The most dramatic example is 1950s San Francisco, a port city whose low rents and mild weather drew artists of the Beat Generation, and then the counterculture creatives of the 1960s. The city developed its legendary aura of cool that, in turn, attracted the thinkers and technologists who built the computer age. Seattle, New York, Berlin, Istanbul, London, Beirut, Shanghai and more can all tell similar stories.

But the cool that art brings soon skyrockets rents, and today few artists can afford the creative neighborhoods of San Francisco, London or Paris. Cool moves on. It’s a cycle seen across the globe, and it presents a challenge to politicians, planners and property developers: how to keep cool sustainable.

Making culture work

It’s to this challenge that Alserkal Avenue brings its own unique cool to the desert of Dubai, just as cultural districts have become parts of the growth strategies of ambitious towns and cities worldwide. Most reflect growth trajectories that are somewhere between unplanned, or “bottom-up,” and centrally planned, or “top-down.”

The top-down model can be seen, for example, in Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District, an area that had been famous for heavy industrialization that was redeveloped into a world-class cultural district. Similarly, in East London’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, greenfield land and nearby neighborhoods are being developed with government funds following the 2012 Olympics.

The bottom-up model is the more prevalent. The Village Underground Lisboa has developed, in the past decade, from a cooperative of creative businesses seeking a shared space for events and coworking. Established with little support from the city of Lisbon, it has more recently attracted major government funding.

In 2013 cultural district developer Adrian Ellis founded the Global Cultural Districts Network, which he currently leads.

Success in any cultural district development, he says, “is an essentially contested concept. Is it the often epic task of just getting it built? Is it the global reach of the art it showcases? Or is it the impact on the social and economic development of the area in which it is located?” Does it raise property values? Has it enhanced the neighborhood, the city—and by what does one measure that?

Essential, Ellis adds, is local consensus on the criteria. It may seem unduly risky to invest large amounts of time and money if the objectives are fuzzy, he explains, but it’s common. Alserkal Avenue’s success so far has come from a blend of gradual experimentation with a factor Ellis is keen to emphasize: supportive leadership.

The Alserkal view

As the sun sets overhead, Alserkal Avenue takes on some of the atmosphere of a movie studio backlot during the golden age of cinema. The architecture may be industrial, but it’s studded with painted scenery from art installations and unexpected blooms of color, light and activity. One of its newest landmark constructions, the graphite-gray box exhibition and forum space called Concrete, stands out, and was a finalist this year for an Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

It’s all a long way from its roots in merchant families who have, in less than a half century, built Dubai, explains Abdelmonem Alserkal, who founded the Avenue in 2008. The physical core of the Avenue, he says, was once a marble factory, one of Dubai’s major imports in the days before its boom. When the factory came to the end of its utility, the Alserkal family saw a chance to build something new in its place.

“The city had reached the stage of growth where it was ready for new development. For culture,” says Alserkal. In 2015 Alserkal initiated the next phase of the district’s development, which added the warehouses that became Concrete. “The Avenue is a promise and statement of belief in the creative talent of the region. But the credit for Alserkal’s success must go to the art galleries, to the creative businesses, to the artists that took the risk of coming into this former industrial area. Through them came the momentum,” he says.

Vilma Jurkute, Alserkal Avenue’s director since 2011, has witnessed and guided the creative flourishing. Under her direction the Avenue’s sense of community and identity has matured, starting from a shared website to orchestrating Avenue-wide events and global partnerships with major arts and culture brands.

“It would have been very easy to create an outpost of Western arts and culture. To grow an authentic culture of Dubai requires tenacity. It requires a belief in your own regional talent.”

As the evening deepens, audiences begin to arrive at Concrete for “Fabric(ated) Fractures,” an exhibition curated by the Samdani Art Foundation, based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The experience of global, high-end cultural venues, long taken for granted in the world’s established “capitals of culture,” is still relatively new in Dubai. While Alserkal Avenue has much in common with other world initiatives, its success story so far stands on its partners and leadership sharing both its aspiration and its practical mission—to bring cool to Dubai and, with it, further economic vitality, even sustainability.

Together, they deeply trust the value of art. The result blends both the consumption and production of the arts, offering a home to makers and to their market, to venues and to audiences. As obvious as these might sound, a healthy balance among these is much to the Avenue’s credit. It bodes well for its future.

Alserkal Avenue shows that risks taken on the work of artists and culture can be worthwhile investments in long-term sustainability and quality of life—even in a city that since just 2016 has added no less than $80 billion to its economy.

“We took a risk on the risk takers,” says Alserkal. “And we have all become richer for it.”

You may also be interested in...

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.

History in Objects: 12th-Century Glass Flask an Islamic Golden Age Masterpiece

History

Arts

Golden Vessel From the Islamic Golden Age Reflects Cross-cultural Connections