The New York of Anthony Jansen van Salee

His 19th- and 20th-century descendants became some of New York’s most glittering glitterati, but when this son of a pirate arrived in the fledgling colonial outpost of New Amsterdam in 1629 and became the first Muslim to own property in the future U.S., conflicts with Dutch authorities nearly undid his ambitions.

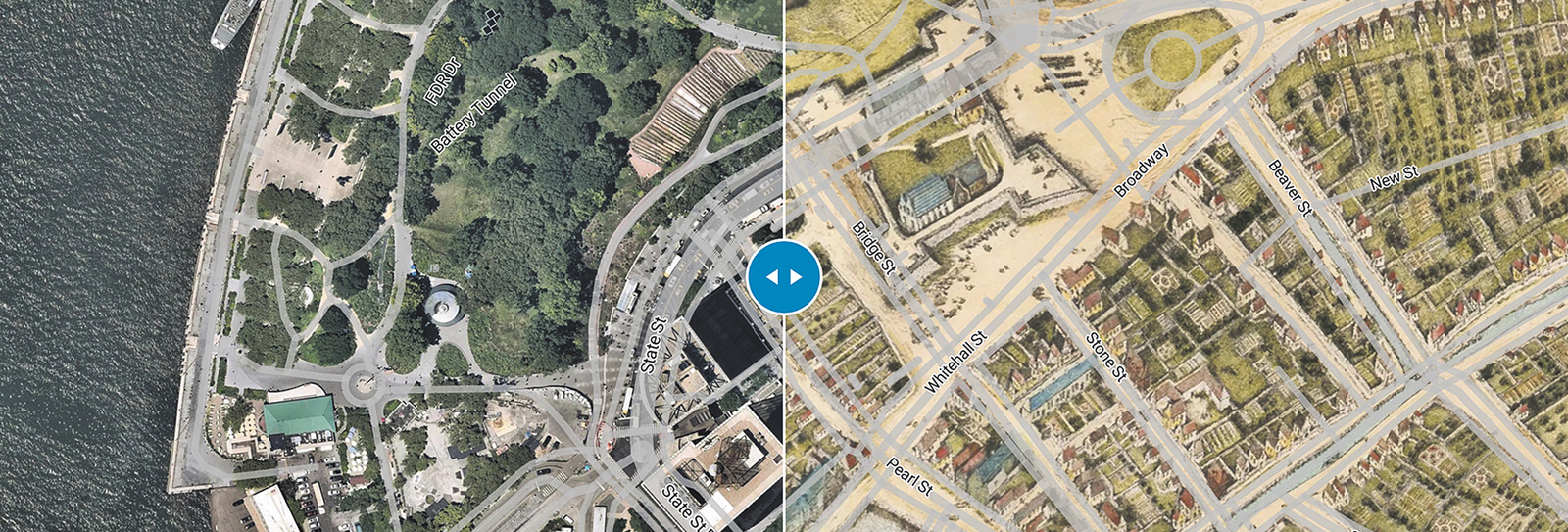

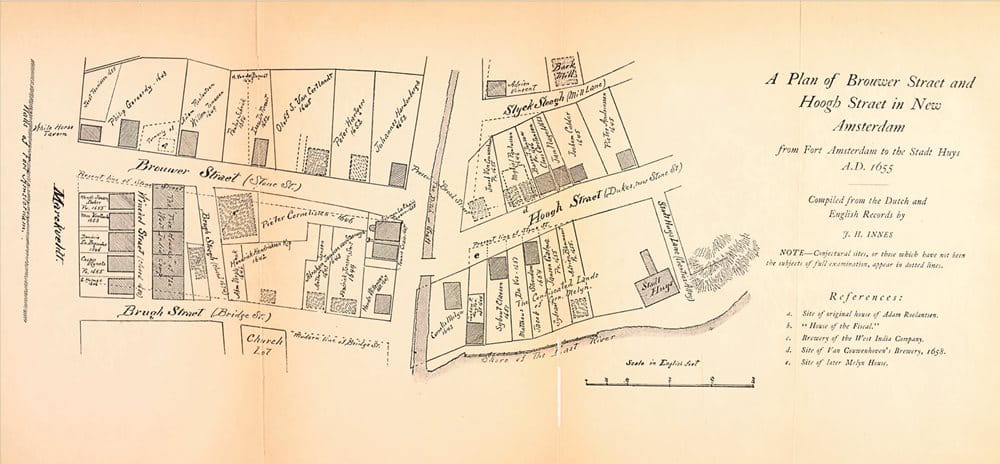

The narrow, rectangular lot pressed between 25 and 31 Bridge Street in Lower Manhattan sits empty save for a few precious parking spaces and a row of dumpsters. A nail salon advertises services on one side, while the White Horse restaurant has bracketed the other since 1641. Across the street, on the ground floor of a steel-and-glass skyscraper, a more modern eatery offers office workers, here in the heart of New York’s Financial District, business lunches to go.

But in the mid-17th century, when Anthony Jansen van Salee, one of the young city’s most successful yet controversial characters, lived here in a handsome Dutch colonial townhouse, the East River, a few blocks away, could be seen from his doorstep.

Son of a career pirate and known for a hot temper and frequent run-ins with neighbors, authorities and courts, he was actually banished from the city at one point. Thus it might seem surprising that he came to own also several other lots in Manhattan as well as agricultural holdings across the East River in the part of Long Island the Dutch named Breukelen—now Brooklyn—and that he became one of early New York’s most-respected citizens. Among his descendants are some of the city’s wealthiest Gilded Age families, including the Vanderbilts and the Whitneys. But considering New York’s historic role as a melting pot, dating to its founding in 1624 as the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam, a figure like van Salee fit right in.

“New Amsterdam was a rather cosmopolitan place, one stop in a vast and expanding Atlantic world,” says Julie Golia, curator of history, social sciences and government information at the New York Public Library. “There would have been people of different races, ethnicities and religions, everything from slaves to passengers to crew on board ships to merchants.”

Van Salee checked a number of these boxes.

“He was the first person from a Muslim background that we know of who ended up settling and owning land in the territory that became the United States,” explains Kambiz GhaneaBassiri, author of A History of Islam in America: From the New World to the New World Order and a professor of religion and humanities at Reed College.

Van Salee’s Islamic roots lie with both parents. His father was Jan Jansen, a rogue privateer from Haarlem in the Netherlands. Originally commissioned to ambush Spanish ships whose commerce competed with the Dutch in the Mediterranean, he eventually turned to independent piracy, attacking any treasure-laden vessel he encountered and flying from his mast whichever flag suited his deception, be it the Dutch standard of the Prince of Orange or the Ottoman crescent.

Sometime around the turn of the 17th century, Jansen was captured by North African pirates. He ended up in Algiers, where he became a Muslim and, taking the name Murad Reis (reis was an Ottoman military title akin to a naval captain), he joined the crew of Barbary pirate Ivan Dirkie de Veenboer, aka Süleyman Reis, another Dutchman who had become a Muslim. (The sincerity of such religious conversions as theirs is a fair question, says Yale University historian Alan Mikhail: “Clearly it was a form of upward mobility, given their circumstances of captivity.”)

After Süleyman Reis died around 1620, Murad Reis moved to the Port of Salé, which the Dutch spelled Salee, on the Atlantic coast opposite the modern Moroccan capital, Rabat. Some 80 kilometers south of the Strait of Gibraltar, Salé proved a safe base from which to prey on approaching ships laden with goods from India and Southeast Asia.

“New Amsterdam was a rather cosmopolitan place, one stop in a vast and expanding Atlantic world.”

—Julie Golia

“During this period of the 17th century, more and more Dutch and English were moving into the Mediterranean, and Salé, even though it is on the Atlantic coast, was very much a part of the Mediterranean world. So that route became very, very lucrative for pirates of all kinds,” says Mikhail, who is also author of God’s Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World.

While nominally subject to the rule of the Moroccan sultan, Salé operated more or less as a semiautonomous city-state whose prosperity owed much to piracy. Reis was appointed governor and commander of the fleet of “Salé Rovers.”

This earned him scorn in the Netherlands. “He behaved strangely, and coarsely disregarded his commission; spared none of the vessels of his own country [and] carried his prizes to Salee to sell his booty,” wrote Dutch pamphleteer Nicolaes van Wassenaer in 1622.

Years earlier, on a voyage to southern Spain, Reis married Margarita, a woman of Muslim descent from Cartagena, a port city with a history as a Muslim stronghold. The couple had four children, among whom Anthony was the third, born in either 1607 or 1608. Before settling in Salé, the family had moved to Fez and then to Marrakesh, in Morocco.

It was from Salé that Anthony, whose Dutch surname identifies him as “Jan’s son” (Jansen) “from Salé” (van Salee), emigrated around 1625 to Amsterdam. He would have been 17 or 18 years old. Four years later he sailed for New Amsterdam, and on the voyage he married Grietje Reyniers, a Dutch Christian.

Dutch colonial records do not specify van Salee’s religion, but they do often refer to him as a Turk, or Anthony the Turk. Later, his property in Brooklyn was known as “the Turk’s farm.” At the time, Turk was used by Europeans to refer generically to any Muslim subject of the Ottoman Empire regardless of the person’s actual ethnicity or place of origin.

“It was a cultural designation, a marker that could identify place [of origin] or religion,” says Mikhail.

While the Dutch at this time were increasingly courting commercial and diplomatic relations with the Ottomans to gain advantage in the eastern trade in spices and other luxuries, the Dutch transatlantic enterprise, the Dutch West India Company (the Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie, GWC), was seeking to muscle in on the North American fur trade against French and English competition.

“He was the first person from a Muslim background that we know of who ended up settling and owning land in the territory that became the United States.”

—Kambiz Ghaneabassiri

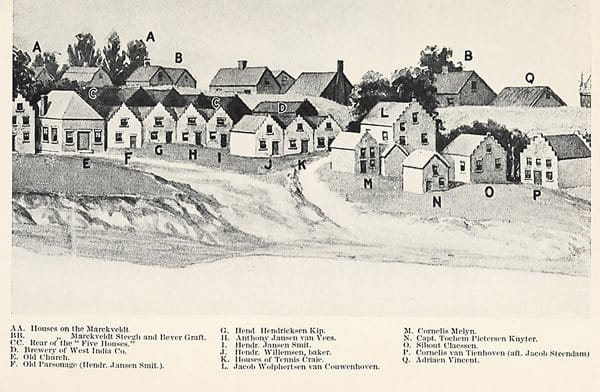

Anchoring that effort was New Amsterdam: part trading center, part military outpost, part breadbasket for the colony. Settlers like van Salee either leased or bought land from the company, and they established farms (bouweries) where they grew crops and planted orchards for the colony. Most individual homes also had gardens and areas for livestock in tightly packed plots of four hectares. The tidy properties fanned out from Fort Amsterdam at the southern tip of Manhattan, an area now known as the Battery, to a walled palisade—now Wall Street—along streets that emulated Amsterdam, with canals (hence Canal Street in Lower Manhattan) and houses with Dutch-style stepped facades. Beyond the palisade lay larger farms of 20 to 80 hectares. Some settlers lived beyond the palisade, and others lived in town, where neighborly squabbles frequently turned nasty and litigious.

“I think what’s really notable about this very small, backwoods colony at the edge of the Atlantic world is that justice was often governed by rumor and slander,” says Golia.

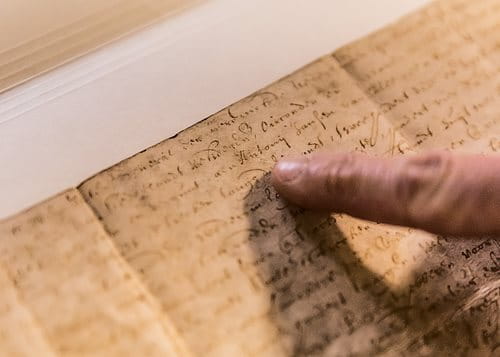

Van Salee found himself at the center of more than a few legal scrapes beginning around 1638. These included accusations of stealing firewood, paying owed wages with a goat that died, fatally siccing a dog on the livestock of a neighbor and brandishing a pistol at a government official. In April of that year, a disgruntled tailor testified that van Salee was “a Turk, a rascal, and a horned beast.” The exasperated judge ruled that both parties go home and “live with each other in peace as becomes neighbors” under threat of a fine of 25 guilders (about $360) if they failed to comply.

A number of the lawsuits van Salee faced were filed in the wake of confrontations with the Rev. Eveardus Bogardus, domine (pastor) of the Dutch Reformed Church, who had arrived in New Amsterdam in 1633. A controversial figure himself, Bogardus had frequent disputes with the colony’s Director General, whom he denounced from his pulpit with accusations of everything from mismanagement to Satanic collusion.

The first formal conflict between the pastor and van Salee took place in June 1638, and it involved a debt of 319 guilders that Bogardus claimed van Salee owed him (the origin of the debt is unclear). The accused acknowledged the debt but countered that in fact the minister owed him 74 guilders. The court ruled that Bogardus owed no more than seven guilders, and van Salee refused to accept the judgement.

“If [the] Domine will have his money at once, then I had rather lose my head than pay him in this wise, and if he insist on [having] the money, it will yet cause bloodshed,” van Salee declared, as recorded by the Register of the Provincial Secretary.

What followed were months of back-and-forth slander in which Bogardus and his allies impugned not only van Salee’s character but also that of his wife. Meanwhile the court, mindful of his threat against Bogardus, decreed in October 1638 that “Anthony Jansen from Salee is hereby forbidden to carry any arms on this side of the Fresh water [about where Canal Street is now] with the exception of a knife and an axe.”

Still the rancor continued. In April 1639 New Amsterdam’s Fiscal (the equivalent of an attorney general) petitioned the court to banish van Salee from Manhattan “inasmuch as the good inhabitants daily experience much trouble from him and his wife.” Director General Kieft acceded, yet in practically the same breath granted van Salee’s request for “a tract of land containing one hundred morgens” (about 80 hectares) in Breukelen. As part of the arrangement, van Salee agreed to pay the GWC 100 guilders annually for 10 years, after which he would “pay such rent as other free people are bound to pay.” It was a shrewd move on Kieft’s part: He could have put the van Salees on the next boat back to the Netherlands, but by banishing them and giving them land, he kept the couple out of the way but on his books. Plus, with the stroke of a pen and a wave of goodbye, he added another sizeable plot to the colony’s lands under cultivation.

For van Salee’s part, the deal proved equally beneficial. The edict apparently only applied to his physical residency on Manhattan, since he continued to buy and sell property on the island, which he leased.

“So, he’s making money off of his land out on the frontier, but he’s also continuing to operate within the growing economy of New Amsterdam,” says Golia.

She and other historians of New Netherland have debated whether, despite the colony’s multicultural makeup, van Salee’s race and possibly faith played roles in his banishment.

What seems most likely, Golia speculates, is that as a Muslim, it wasn’t so much what van Salee said or did but what he didn’t do: attend church or donate to the parish from which Reverend Bogardus took his living.

In 1674, two years before his death, van Salee was listed among “the 1,000,” a tax list of the wealthiest residents of what was by then called New York.

“Both Anthony and Grietje showed a defiance toward the authority system,” and in New Amsterdam, says Golia, that meant the church.

Mikhail suspects that a land grab may have been another motivation for ousting van Salee, who was sitting on a good bit of what yet remains some of the priciest real estate in the U.S.

“New Netherland started off as a trading post, and it was not meant to be a permanent settlement in the first few years,” Mikhail points out. “Once it became more permanent, things like land claims and property disputes became much more intense.”

Florida chiropractor Brian Smith, a direct descendant of van Salee, agrees. In 2013 Smith wrote a biography of his ancestor for fellow descendants. In his own review of Dutch colonial court records, Smith concluded that many of the lawsuits coincided with unsuccessful attempts to buy out van Salee’s land on Manhattan.

“All of a sudden there were all these slander charges: nine in a month. When I analyzed the lawsuits, I said, ‘Wait a minute, it’s everybody else filing lawsuits against them. They’re not filing lawsuits.’ Of all the lawsuits I found, they filed one-third of them, but two-thirds of them were against them, the majority of which they won, which means they were in the right,” Smith says.

What is more certain is that van Salee made the best of his exile. Reputed to have been tall and strong, he put his back into turning profits from the “Turk’s farm.” Today, nothing of it remains, and yet the Wyckoff House Museum, in nearby East Flatbush, home to some of the last remaining undeveloped farmland in Brooklyn, recalls it and other early Dutch agricultural homesteads. Dating to 1652, the original portion of its low-slung, clapboard-and-shingle farmhouse is New York City’s oldest standing structure. Garden manager Zachary Tan Strein says the historic property offers a glimpse of what van Salees’s homestead might have looked like.

“There would have been a lot of marsh and woodland to clear, but early settlers managed to grow pumpkins, tobacco, salt hay and flint corn, which they got in trade with the local Lenape Indians,” says Strein, who tends the site’s 15-by-15-meter garden that features heirloom crops representative of van Salee’s era.

In addition to expanding his family to include four daughters, van Salee also added yet more land to his holdings, ultimately becoming one of the largest landowners on Long Island. This began to shift his reputation, and as the late New York State historian Victor Hugo Paltsits noted, van Salee actually became one to whom disputing parties turned for advice, “esteemed for his knowledge of the old boundaries of land on Long Island.”

It was not long until he was back in Manhattan in person, presumably with a wink and a nod from the authorities, living in the Bridge Street house he had purchased a few years earlier. Appropriately enough, given the neighborhood’s future as a center of world commerce, van Salee made a profitable living there, too, as a merchant and moneylender.

In 1660 van Salee sold his land in Brooklyn, and in 1664 the Dutch surrendered New Amsterdam to the British without a fight. After Grietje died in 1669, van Salee remarried and lived seven more years on Bridge Street. Two years before his death, he was listed among “the 1,000,” a tax list of the wealthiest residents of what was then called New York. All four of his daughters married into leading families, and today, in addition to direct lines to the Vanderbilts and the Whitneys, van Salee’s descendants include US presidents Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt; actor Humphrey Bogart; Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and CNN news anchor Anderson Cooper.

But the significance of van Salee’s legacy extends even further.

“He was representative of the larger connections that made up the Atlantic world, and Muslims were very much a part of that makeup,” GhaneaBassiri says. “Figures like Anthony van Salee are reminders of a history that we don’t really remember of the United States, that there were all sorts of connections to Europe and the rest of the world that went through Muslim-majority societies.”

You may also be interested in...

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Pearls, Power and Prestige: The Symbolism Behind Byzantine Jewelry

Arts

History

A 1,500-year-old gem-encrusted Byzantine bracelet reveals more than just its own history; it symbolizes an empire’s narrative.

How California's Date Fruits Became America's Arabian Superfood

Food

History

In recent years in the United States, dates have been trending as a nutrient-dense, easily transportable source of energy. Nearly 90 percent of US-grown dates are from California’s Coachella Valley. Yet the date palm trees from which they are harvested each year aren’t native; they were imported from the Arab world in the 1800s. Over the years, they have become a part of Coachella’s agricultural industry—and sprouted Arab-linked pop culture.