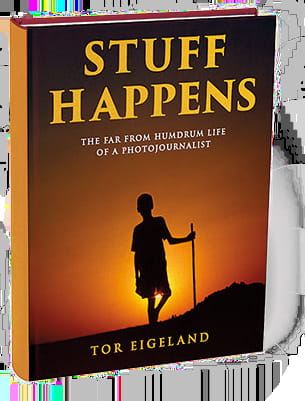

Photojournalist Tor Eigeland set sail from his hometown of Oslo in 1947 at age 16, and he never looked back until he had completed his last photography assignment, in Tangier for AramcoWorld in 2016. Transitioning from sailor to photographer in his early 20s, during those travels, he learned one truth: Stuff happens. This is also the title of his book, in which each of the 51 chapters follows one of his hundreds of adventures and assignments—capturing people at the height of their power or fame, including Fidel Castro and King Hussein of Jordan, to those dying of AIDS in Africa. Some were moments that changed the course of history, like when the USSR’s Nikita Khrushchev and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser inaugurated the building of the Nile’s Aswan Dam in 1970. But this is in not a reprint, retrospective or rehash of his work. Rather it is an introspection of what it meant to be there, to be a journalist and a human being in these places. Eigeland’s compassion for those he met as well as the humor with which he looks back at his days on the road are what make the book so special. Well, and that it presents an incredible archive of photos. Eigeland also delights in sharing random encounters with the likes of Olympic gold medalist Johnny Weissmuller and novelist Norman Mailer while doing his work, adding a quirky twist to this compelling memoir.

You've had such a long career and so many experiences, how did you choose what stories to tell?

I knew I could only write about the highlights, the ones of now historical interest, ones which others have enjoyed hearing when I get to storytelling. I wrote the first pages about 10 years ago—the background of how I got bitten by the travel bug. It was COVID that rocketed me into fast-forward. Lockdown wasn’t pleasant, but it gave me time to concentrate on finishing my book. It definitely doesn’t include everything I’ve done—what was fascinating to me might not be to a reader.

If you could revisit any of the subjects or locations from your book, which would you choose?

Without a doubt I would return to the Marshes of Iraq, where I went for a story for a Time Life book in 1967 and observed the lives of the Marsh Arab and their 5,000-year-old civilization. Their ancient world still remains brilliantly alive in my memory and, fortunately, through my photos. From the moment my little boat floated into the tranquil marshes, there was water everywhere, small lakes and canals with reed dwellings on little reed islands, thousands of birds and water buffalo. The outside world ceased to exist. It was magical. I also really liked the people, many of whom had never had any contact with outsiders. That was all prior to their sad destruction and the draining of the marshes in the 1990s. Revisiting would obviously be tinged with much sadness, as so much has changed. Nonetheless, I would like to see with my own eyes whether the current efforts at restoration are making any real progress.

Of the more than 50 stories you’ve covered for AramcoWorld, what stands out most?

My favorite assignment was titled “Scenic Arabia: A Personal View” and was published in 1975. I wrote and photographed every single article in that issue, so it became quite a personal achievement. This “special edition” included organizing planes, cars and people, and I had a lot of ground to cover in a short time.

If you were to make a bigger book, what other stories from your career would you include?

Before handing over my manuscript to the publisher, there comes a difficult moment when you think, “What else?” I actually spent about six months in Indonesia and about the same amount of time in South Africa and Australia. Apart from a small mention of South Africa, none of that is included. The truth is that these trips, and many others, have faded in my memory. I’m short of photos for these locations, and I wanted to limit the size of the book.

You have a love of languages and speak four fluently. Is there an expression you learned along the way in any language that sticks with you?

Inevitably, the expression or word that instantly springs to mind is inshallah, used as an expression of hope, as in, “We will meet again tomorrow, inshallah.” I think the word is also vaguely related to the title of my book, Stuff Happens. There is an element of fate, a shrug, an acceptance of whatever will be, the c’est la vie in French.

You may also be interested in...

‘Home’: Arab American National Museum Celebrates 20th Anniversary

Arts

Arab American National Museum Director Diana Abouali says the facility—which is marking its 20th anniversary in 2025—in Dearborn, Michigan, has aimed to create a home for Arab Americans by preserving and presenting the history, culture and contributions of Arab immigrants as well as their native-born children and grandchildren.

Othman Almulla Embodies Arab World’s Dream of a Golf Championship

Culture

The journey of Saudi Arabia's first professional golfer parallels that of the region from humble beginnings to leaderboard for the global game.

Handmade, Ever Relevant: Ithra Show Honors Timeless Craftsmanship

Arts

“In Praise of the Artisan,” an exhibition at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, aims to showcase Islamic arts-and-crafts heritage and inspire the next generation to keep traditions alive.