Rajasthan's Folk Musicians: Exploring How and Why Music Matters

History

Anthropology

South Asia

Connect the influences of music within one Indian community of professional musicians.

The following activities and abridged text build off “Rajasthan’s Folk Musicians Find New Ways To Play,” written by Scott Baldauf and photographed by Poras Chaudhary.

WARM UP

Scan the article’s photos and captions to predicts its theme and main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Review three common influences that inspire music. Examine how these influences motivate Manganiyar musicians, and compare your findings to your favorite music.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Review information from text and video sources. Compare the two sources for how well each helps you understand the subject of Manganiyar music.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Develop content (images and video clips) for a promotional package to tell audiences about Manganiyar music.

Directions: As you read, you will notice certain words are highlighted. See if you can figure out what these words mean based on the context. Then click the word to see if you’re right.

Rajasthan's Folk Musicians Find New Ways To Play

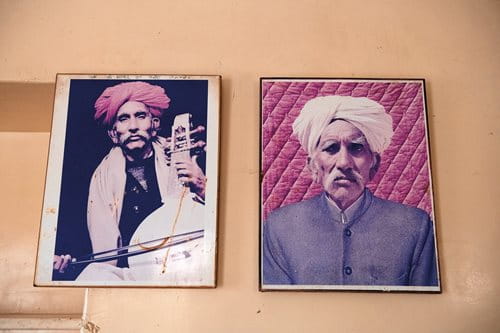

Lakha Khan closes his eyes, takes a breath and pulls a rosined bow across the stringed instrument in his lap. The hand-carved wooden sarangi emits a drone with unexpected power, piercing like the cry of a hungry infant in a concert hall but soothing like a lullaby. It’s a sound that resonates, an otherworldly note from the beginning of time.

After a moment, Lakha Khan adds his own voice, raspy and warm. He sings a love story hundreds of years old. Most Indian love songs are about a boy and a girl. But this one is about the love between man and God. There is something timeless about this song that rises above the chatter of the everyday. It acknowledges pain and comforts broken hearts.

“When I start playing, it is sounding sweet from the first note,” says Lakha Khan. “I feel a direct contact with God when I play.”

How do Lakha Khan’s songs differ from typical love songs?

They are about love between God and humans.

Question: How does Lakha Khan feel when he plays music?

He feels connected with God.

Born To Play

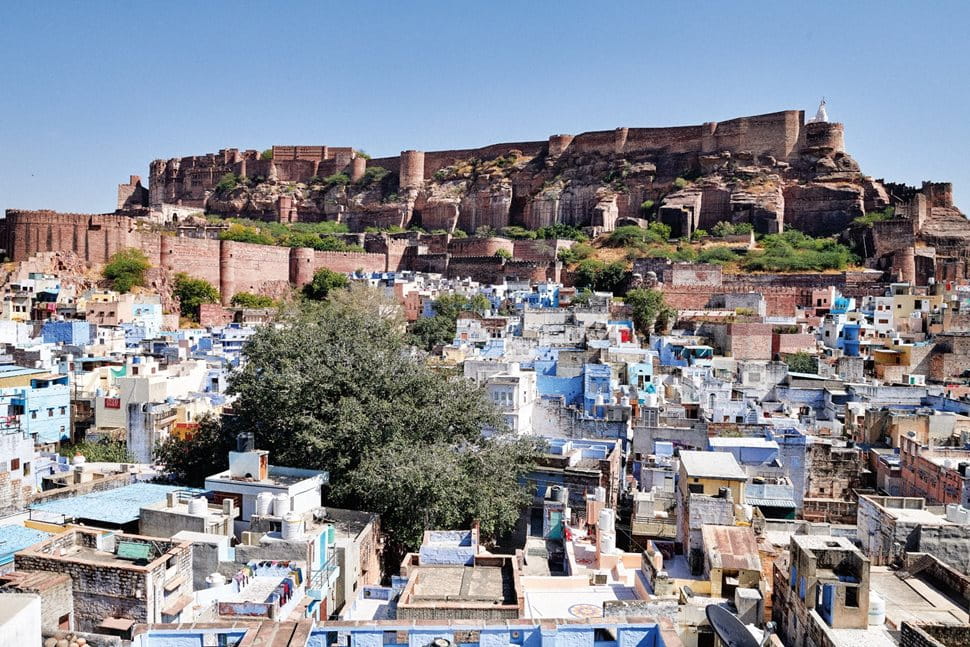

For centuries Indian musicians such as Lakha Khan have held a privileged position. They have held the cultural traditions, history, music and memory of their communities. In Rajasthan professional musicians like Lakha Khan—who are Muslim—serve as the principal curators of Rajasthani culture, including songs of celebration for all communities. No birth, wedding or funeral—no major event—happens without them.

Question:

What role do professional musicians play in Rajasthan?

They are guardians of the culture and traditions.

Question: What analogy does the author make between Manganiyar music and Appalachian folk music?

The author says that both forms of music, while native to a particular place, transcend that place and become valued by others.

Lakha Khan’s community comprises a hereditary caste of professional musicians called Manganiyars. They begin their training from their elders as children and become experts over time. Folk musicians invite sing-alongs. Manganiyars, however, collaborate with classical masters.

Manganiyar music is specifically written for a society that is alien even to most Indians—a world of arid isolation at the edge of India’s largest desert, the Thar. But just as Appalachian folk musicians broke through ages of prejudice to pave the way for modern country music in the United States, the stories and songs of Manganiyars evoke an emotional power that transcends the borders of languages, cultures and even national origins.

Lakha Khan’s fans first notice his voice. Its keening tones invite comparisons to the rugged power of bluegrass singer Ralph Stanley or blues singer Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter. Some voices just pierce through the howling wind, pass through you and leave you wanting more.

For inspiration, Lakha Khan turns to his faith, even if he is performing for audiences with other belief systems.

“For us, there is only one God,” he said. “Bigger than the night is the sky. Bigger than the sky is the word. Beyond words there is nothing, and in that nothingness is where the Lord is.”

Preserving Culture

But Manganiyars, and the music they preserve, are threatened. Economic changes are making it harder for Manganiyars to get paying gigs. As a result, many young Manganiyars are leaving the family business to find work in the big city.

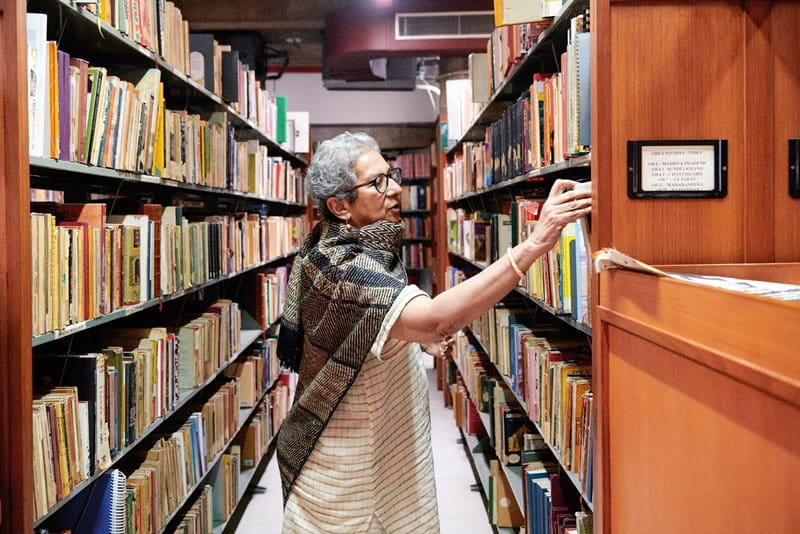

Will centuries of traditional music die with the aging masters? Not if ethnomusicologist Shubha Chaudhuri has anything to say about it. For 40 years, Chaudhuri has been making field recordings to preserve Rajasthani music before it is lost.

Question:

How is Shubha Chaudhuri preserving Manganiyar music?

She and her colleagues are recording the traditional music.

“In our modern society, people don’t want to listen to something that is longer than three minutes,” Chaudhuri says. But not all traditional music fits into that format. Often, Manganiyar musicians perform compositions that last for hours.

“Lakha Khan is the only one of his generation left now,” Chaudhuri says. “He knows the whole repertoire.” And when his generation passes on, they will take much of this music with them.

Chaudhuri’s solution has been to document the songbook of the Manganiyars and Langas. She is following the lead of father-and-son team, John and Alan Lomax. The Lomaxes traveled rural America from the 1930s to the 1960s, recording work songs, blues and ballads for the US Library of Congress. In that vein, Chaudhuri began in the 1980s to visit villages across Rajasthan to record its musical traditions.

Much of the material Chaudhuri and her team have gathered is now available for paid download on Smithsonian Folkways Recordings at folkways.si.edu. The Folkways repository preserves tradition and gives Rajasthani musicians income from the download sales.

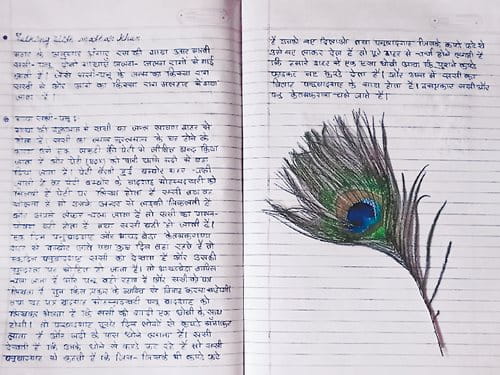

Other programs are expanding the preservation effort. Archivists and folklorists have trained young Manganiyars to identify, interview and record the older generation of musicians. Like Chaudhuri, they aim to preserve the great Rajasthani songbook before it disappears.

Question: How are others preserving Rajasthani music?

By training young people to interview and record the aging musicians

Building New Stages

Like Chaudhuri, Ashutosh Sharma gathers field recordings of traditional Rajasthani musicians. But his methods and motives are different. Sharma hopes that high-quality traditional music will find a market among a new generation of Indian youth.

Question: What is a third way people are preserving Rajasthani music?

By bringing it to people in other forms

“The audience for this music exists,” says Sharma. He is founder of the New Delhi-based Amarrass Records, which promotes regional musicians. With friends, Sharma has helped musicians to take their music to world music festivals in Europe and the US.

With Amarrass’s help, Lakha Khan toured in Germany, Portugal and Canada in 2022. Another Amarrass client, the Barmer Boys, have performed their mix of Rajasthani traditional music and hip-hop at festivals in Germany, Spain and Netherlands.

“A lot of American artists made it in Europe first before they made it back home,” Sharma says. “The same thing proved true with our artists. As they got big abroad, they got more accepted back here in India. With the Barmer Boys, our initial plan was to get them onto the popular Indian TV show Coke Studio. But in two years, they were playing with Outkast and the Rolling Stones.”

To give musicians greater exposure closer to home, Amarrass has set up a monthly concert series in Delhi called Amarrass Nights. Music lovers listen to a wide variety of regional musicians from north and western India.

While the bands that play there differ from each other, they all share a similar perspective. As musician Jumme Khan sings, “You can divide anything you want on earth, but how can you divide the open sky? There is just one god,” he adds, “yours and mine.”

Sarrjeet Tamta, the lead singer of Rehmat-e-Nusrat, turns the focus toward the divine creator of all, in the popular qawwali tune “Allah hu” (which means “God is”).

There is no one like you

And that is your grandeur, O unique one

You are the imagination and the inquisitiveness,

You are the wish

You are the light

and the voice of the heart

You were there, you are there, and you will be there

God is, God is, God is.

It’s striking that Tamta, like most of his audience, is not Muslim. He was born Hindu into a family that performed Hindu religious music. But now he prefers the timeless poetry of Amir Khusrao and Nizamuddin Dawliya, which promotes open-mindedness, inclusiveness and hope.

A New Generation

In Hamira village, brothers Ghewar and Firoze Khan keep the spirit of their father’s music alive. Sons of Saker Khan, the first Manganiyar to receive the Padma Shri, one of the highest civilian awards in India, The two brothers perform for their Hindu patrons in Hamira. They also perform across India, Europe and North America.

They learned their trade from their father, starting as children. They began performing with the family and gradually gained proficiency. Ghewar learned his father’s instrument, the kamanche, while Firoze played the barrel-shaped dholak drum.

Now, like his father, Ghewar has students of his own: his own children and other relatives, and even a few foreigners from England and the US. Some local musicians have left Hamira, and regional traditional music behind. But not Ghewar.

“This is my profession, this is something I was born to do,” Ghewar said. “The next generation will decide if they are interested in carrying on with it.”

Ghewar and Firoze play music at home, joined by Ghewar’s four-year-old grandson Ayan. The two men urge the boy to sing along or to try the kamanche or dholak.

Firoze puts a kamanche in his lap. The instrument is easily as large as the boy. Ayan holds the bow perfectly with his left hand, but shakes his head. “You better tune this,” he said. “You can’t just let me play it.”

The old men are patient and offer encouragement. This is how they first encountered music, taught by their elders through play, not pressure. And this is how the new generation will take up the mantle. A cycle of renewal begins again, through play.

Other lessons

Spaces for All

For the Teacher's Desk

Built environments can foster community within cities and neighborhoods and change how we view the world.

Tracing the History and Geography of Portuguese Tile Making

Geography

Architecture

Europe

Analyze how culture and technology have changed the ways tiles have been made in Portugal for over 500 years.

The Hill Rice Connection: Trace Its African Diaspora Roots and Examine How Communities Sustain Its Heritage

History

Geography

Anthropology

West Africa

Americas

Explore the connections between rice and African American agricultural history and analyze how hill rice connects to African American agricultural history and examine the Gullah Geechee community’s efforts to preserve this heritage through cultivation and storytelling.