Author Giulia Paoletti Traces History of Senegal’s Photography

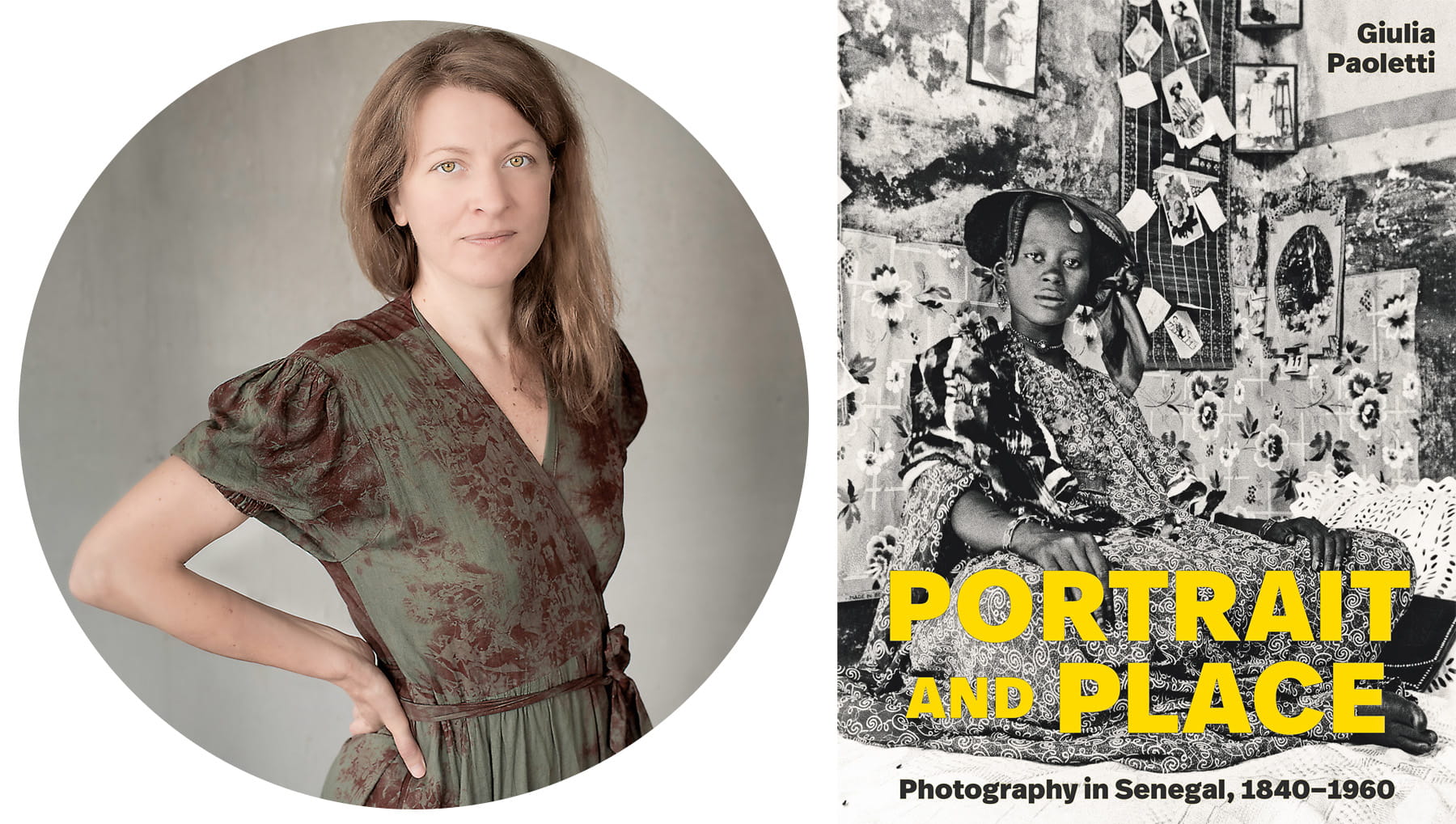

Art historian Giulia Paoletti discusses her book Portrait and Place, exploring the rich but largely undiscovered history of photography and portraiture in Senegal.

6 min

Written by Dianna Wray

Growing up in Padua, Italy, Giulia Paoletti learned the canon of Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Botticelli like every other student. But her studies abroad at Sussex University in Brighton, UK, opened her eyes to a wider world of art—and to the striking absence of Africa within it. That gap shaped the path of her career.

Encouraged during graduate work at New York’s Columbia University to pursue a subject she truly loved, Paoletti turned to Senegal, a country whose photographic traditions stretched back to the 1840s yet had barely been studied in art history. She spent more than a decade researching, including three years living in Senegal, learning to speak Wolof—the country’s national language—and conducting more than 100 interviews. The result is Portrait and Place: Photography in Senegal, 1840–1960, a book that rethinks how photography took root in West Africa.

AramcoWorld spoke with Paoletti about uncovering overlooked histories, the meanings embedded in images and why context matters so much.

Portraits and Place: Photography in Senegal, 1840-1960. Giulia Paoletti. Princeton University Press. 2024.

What drew you to study Senegal’s history with photography?

I had taken a photography course when I started my Ph.D., and I just fell in love with the medium. Contemporary art can often be difficult to approach because you need some framing, some intellectual scaffolding, while photography affects you so much in the immediate moment, no matter where you are in the world. In Senegal I found that they have a long history with photography and the Senegalese were so engaged with the medium. Incredible photos were produced, and incredible artists existed, but when I started, I realized there hadn’t been a lot of serious study of this history.

Why do you think Senegalese photography was overlooked for so long?

Initially, it wasn’t considered an art anywhere. Even in the West, photography was not considered an art for a long time. It took many decades before we had the first exhibitions at MOMA. And since it was not considered an art in most places, it was not collected, studied and valued as a craft. So even if some of these images that I’ve pulled together in the book were seen when they were being produced, they were not necessarily seen as items worth studying and preserving.

Why is the context so crucial for these photos?

We often think that images are passive and that there’s one meaning, that when it was snapped the meaning was done. But in fact, an image can mean so many things based on who is seeing it and when they’re seeing it and who constructed it.

With this book we need to see that we are still contributing to its meaning and that we are not passive in our viewing. Even in a photo taken by a colonial photographer, there are many ways to look at the image, and some of those ways undo certain assumptions and certain power relations about who is in control of that image, who is shaping what we see.

Unknown artist’s “Group Portrait With Record Player,” c. 1920s-1930s, postcard-format gelatin silver print, 7 inches by 4½ inches (17.8 cm by 11.4 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

How did learning to speak Wolof impact you and your work?

It was really transformative. I had never studied a non-European language before, and Wolof has such different grammar and syntax that it completely changes how you say things, what you ask and don’t ask, how you move, even how you talk in other languages. Each word has worlds of meaning in it, and understanding that helped me better understand the people I was interviewing. It really opened up a part of Senegal that I don’t think I would have been able to experience any other way.

In more than a decade of research, what was the most exciting moment?

I was lucky enough to interview [famed Senegalese photographer] Oumar Ka before he died in 2020. He still had his studio, and at one interview he hauled out a suitcase filled with negatives, images I wasn’t going to find anywhere else in the world. It was incredible.

What was the most important thing you learned over the course of this project?

That this has to be a conversation, one where I always ask questions and remain open to the answers, to wherever the conversation takes me. I think that’s the only way one can learn: by being exposed to another perception, to other points of view.

You may also be interested in...

Couscous for Lunch or Dinner: Algerian Pasta Soup With Labneh

Food

The berkoukes are giant couscous balls cooked into soups and stews, with little differentiation across North Africa and the Levant.

Ramadan Nostalgia Requires Active Reconstruction

Arts

Artists demonstrate how Ramadan traditions endure through deliberate acts of memory and care.

2026 AramcoWorld Calendar - Football Is Life

Culture

In urban centers and tiny villages, amid plains, deserts, forests, rainforests, coastal areas and any other habitat on our spinning sphere, football found a formidable foothold.