Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

ACT 4, SCENE I

The ruins of an ancient Roman amphitheater, night. An evening breeze stirs the colonnades. Starshine dusts ancient stone, and somewhere, a voice begins:

“Are you sure that we are awake? It seems to me that yet we sleep, we dream.”

—A Midsummer Night’s Dream

The scene is set not in London. Rather, among modern stages and the ruins of Roman amphitheaters scattered across the Middle East, a familiar voice drifts—Shakespeare's. His words, though forged in distant skies, find new life in stone and stage alike. And in the liminal hush between cultures and time, a timeless drama begins again.

Shakespeare's works have become part of the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but the influence flows both ways. His plays were shaped, in part, by the cultural presence of the Islamic world, from its storytelling traditions to the political realities of the Mediterranean. And that same depth of exchange lives on. From the first recorded performances an Arab stages, the Bard's themes—love and betrayal, justice and tyranny, exile and redemption—endure. Through translation, adaptation and reinvention, his plays have taken root across the region.

From the theaters of Cairo to the studios of Beirut, artists continue to reshape and breathe new life into his stories.

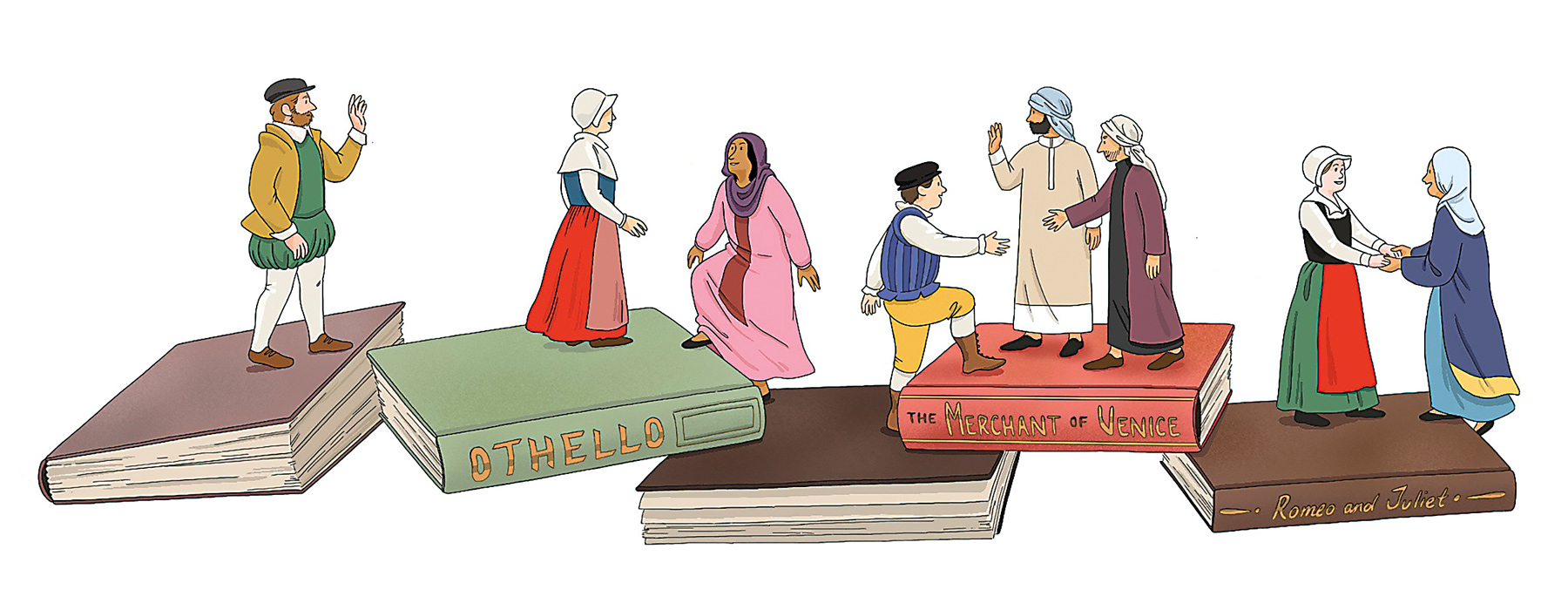

While the titular character of Shakespeare’s “Othello” is widely known as a Moor, other examples from Muslim cultures shaped plots and themes in several of the playwright’s comedies and tragedies.

Theater against backdrop of trade

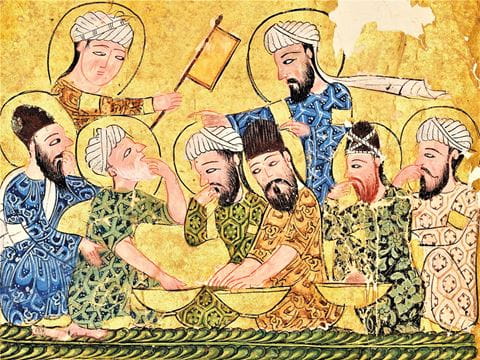

When Shakespeare arrived on the London stage, the Islamic world was no distant fiction; it was deeply woven into the global and political imagination of the day. England under Queen Elizabeth I had entered diplomatic relations with the Moroccan sultanate and pursued trade with the Ottoman Empire.

Ambereen Dadabhoy, a scholar of Shakespeare and early modern English literature at Harvey Mudd College, in the United States, argues that Islamic cultures function as a kind of "shadow text" in Shakespeare's plays—present, influential but rarely named.

Her book Shakespeare Through Islamic Worlds examines how Islam and Muslim cultures shape the plots, themes and emotional texture of his works, from Mediterranean tragedies to English histories.

Focusing on the Muslims at the margins of Shakespeare's works, she reveals how Islam informed the cultural imagination that underpinned the playwright's world.

Characters like the Prince of Morocco in "The Merchant of Venice" and Sycorax in "The Tempest," respectively, are geographically tied to Islamic cultures, yet their faith is never explicitly named. "If [the Prince of Morocco] is the Prince of Morocco, he can only be a Muslim," Dadabhoy writes, pointing to Shakespeare's strategic ambiguity. Sycorax, an unseen sorceress, is described as being "from Algiers"—a Muslim-majority locale that again signals Islamic presence without direct identification.

These omissions, she suggests, are not accidental but reflect a broader "evacuation of Muslim presence" from settings that were historically multireligious and multiethnic, a selective forgetting that renders Islam as ambient but unspeakable. That cultural omission sat against a backdrop of real diplomatic engagement. Professor Michael Dobson, director of the Shakespeare Institute at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, notes, "There was widespread anxiety across Christian Europe about the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. North African alliances and fears were part of Shakespeare's geopolitical backdrop."

Shakespeare's audience would have been acutely aware of recent diplomatic exchanges with the Islamic world. Dobson adds, "In 1600, Elizabeth I received an embassy from the sultan of Morocco, Ahmad al-Mansur. His ambassador, Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud, is believed to have presented her with a portrait—now hanging in the Shakespeare Institute"—amid discussions of a possible alliance. Just four years later, Shakespeare wrote "Othello," a play that imagines a Christian military campaign against the Ottomans in Cyprus. Though the battle itself is fictional, the anxieties it evokes reflect real diplomatic and religious tensions of the time.

This political reality left traces in Shakespeare's plays. Sycorax, as noted above, signals a shadowed Islamic identity through her geography. And the proud Prince of Morocco enters with noble bearing and coded references to Islamic culture, without ever being named as Muslim.

Such connections, Dobson says, enriched Shakespeare's dramatic choices. "These characters existed within a larger political context that Elizabethan audiences instinctively recognized."

That ambient presence contrasts with the richness of Islamic storytelling traditions that leave their mark on the emotional and poetic fabric of his plays.

These very traditions, often overlooked in Western literary criticism, are central to understanding why Shakespeare continues to resonate so powerfully in the Arab world.

Tales of vengeance, exile, disguise and redemption—long staples of Arabic narrative—find new expressions in Shakespeare's drama and also explain why his work continues to captivate Arab audiences, artists and thinkers alike.

The Bard was shaped, in part, by the Islamic world’s storytelling traditions and political realities of the Mediterranean, of which his audience would have been aware.

These characters, from East and West, remind us that the real battlefield is often within ourselves.

Crossroads of love and tragedy

Arabic literary traditions not only shaped Shakespeare's political imagination but also the emotional architecture of his romances.

Ruqayya Khan, professor and Malas Chair of Islamic Studies at Claremont Graduate University, points to the deep parallels between "Romeo and Juliet" and the legendary Arabic romance "Layla and Majnun," first recorded in the ninth century.

"Both stories center on star-crossed young lovers," Khan explains. "Their eloquent declarations of love are doomed by social and familial conflict. The emotional turbulence, the tragic twists and the ultimate deaths, especially the despair of the male lover, are hauntingly similar."

Although Shakespeare likely never encountered "Layla and Majnun" directly, he inherited a literary tradition shaped by centuries of Arab and Persian romance.

Similar currents can be found in "Khosrow and Shirin," a Persian epic absorbed into Arab storytelling, and in the Arab world's Udhri poetry, a genre of chaste, tragic love ballads where intense passion meets inevitable separation.

Such traditions formed part of the rich cultural atmosphere, by way of Spain, Italy and the eastern Mediterranean, that infused Shakespeare's tragic vision with echoes of Eastern love stories.

Shakespeare's vibrancy across the Arab world

Dadabhoy helps contextualize why Arab artists and audiences continue to engage so deeply with Shakespeare. She writes, "The Shakespearean Mediterranean excludes Islam, despite Islam's geographic and historical presence in that space." Re-engaging with Shakespeare from the Arab world becomes, in her framing, not only artistic but also a corrective act, repopulating the stage with voices that had been sidelined.

Today Shakespeare's plays continue to find vibrant life in Arab contexts through their shared human concerns—justice, loyalty, love and pride—as well as as powerful lenses for political critique and cultural dialogue.

According to Yousef Abu Amrieh Awad, a scholar of Shakespeare in the Arab world, Arab writers have historically approached the Bard in diverse ways. "Some have tried to mimic his works in a way to reflect their understanding within their original context. Others have adapted Shakespeare's plays to suit local tastes and traditions."

Syrian playwright Mamduh Adwan's "Hamlet Wakes Up Late" (1976), for example, reimagines Hamlet as an intellectual paralyzed by moral debates and unable to act decisively. In "Romeo and Juliet in Gaza" (2016), Palestinian director Ali Abu Yassin reframes the classic story of forbidden love within a local context, while Iraqi director Munadhel Dawood's "Romeo & Juliet in Baghdad" (2012) reimagines Shakespeare's lovers within contemporary Iraqi society.

Awad describes these adaptations as part of a "rhizomatic relationship," where Shakespeare's texts branch into local cultural narratives, sprouting sequels and reinterpretations of adaptations themselves, such as Jordanian playwright Zaid Khalil Mustafa's "Hamlet, A While After" (2018), which continues the story as a sequel to Adwan's adaptation rather than to the original play.

This dynamic extends to literature. Arab diasporic writers appropriate Shakespeare's themes to interrogate modern crises. Syrian British novelist Robin Yassin-Kassab's The Road from Damascus (2008), Sudanese British novelist Jamal Mahjoub's The Fugitives (2021) and Palestinian British novelist Isabella Hammad's Enter Ghost (2023) all draw from Hamlet to explore political displacement, cultural identity and resistance. These, Awad notes, are "intelligently written 'palimpsestuous' novels" that stand alone yet evoke Shakespeare's timeless concerns.

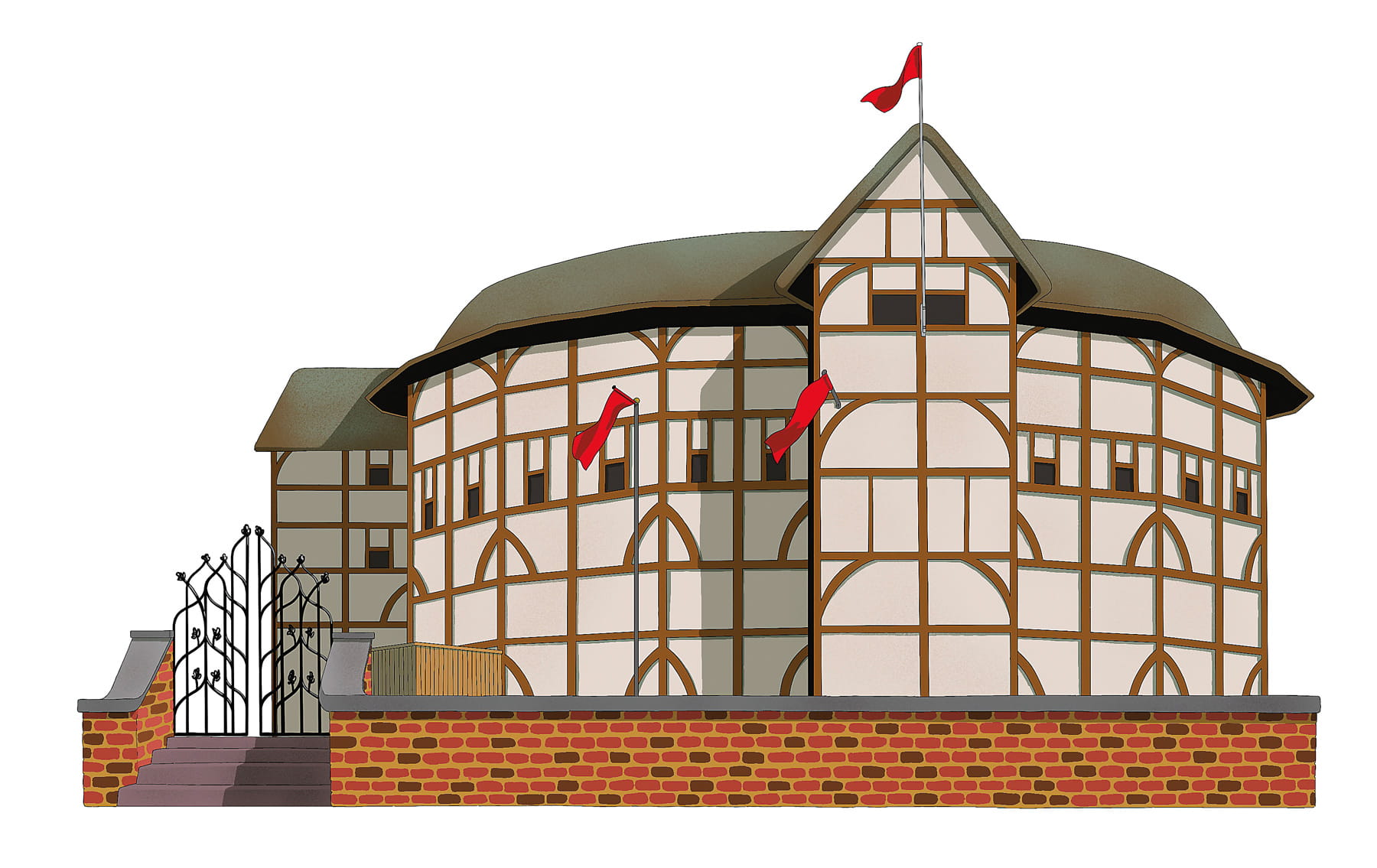

The Shakespeare and Islam season at London’s Globe Theatre in 2004 saw reinterpretations of the Bard’s timeless tales of grief, joy, love and loss come to life.

Spiritual longing in the Bard's and Islamic works

But the Bard's work is also infused with a spiritual longing that resonates deeply with Islamic traditions. As Luqman Ali, founder of the United Kingdom's Khayaal Theatre Company, reflects, in both Shakespeare and classical Islamic literature, characters wrestle deeply with questions of morality, fate and the human soul. "Just as Rumi's lovers and wanderers must lose themselves to find the Beloved, Shakespeare's stage becomes a mirror for the soul's own hidden pilgrimage—an invitation, even today, to seek what lies beyond the surface of the world."

Ali draws vivid parallels: Shakespeare's Portia, a protagonist of "The Merchant of Venice," like Scheherazade of One Thousand and One Nights, uses wisdom and heart to transform injustice into mercy. Shakespeare's "Henry V" shares traits with the chivalric heroes of "The Tales of the Marvellous" and the epic the "Hamzanameh"—figures defined not merely by victory but by ethical trials of character. "These characters, from East and West, remind us that the real battlefield is often within ourselves," Ali says. They offer archetypes that "answer a deep human longing for meaning and self-knowledge."

At Khayaal Theatre, Ali has reinterpreted Shakespeare through the spirit of the Arab hakawati, the traditional marketplace storyteller. During the Shakespeare and Islam season at London's Globe Theatre in 2004, Khayaal's "Souk Stories" brought tales of grief, joy, love and loss to life in bustling communal spaces.

"Through the spirit of the souk [market]," Ali explains, "Shakespeare's plays return to what they have always been at heart: human stories meant to be shared, pondered and lived."

In these performances, Shakespeare's characters become kin, their dilemmas recognizably our own.

Rather than a relic of empire, Shakespeare emerges as a living, breathing bridge: a testament to the shared moral struggles, dreams and dilemmas of humankind. As Arab audiences, artists and scholars continue to read, stage and reimagine Shakespeare, they remind the world that the Bard belongs to the souk as much as to the stage; to Riyadh and Cairo as much as to London; and to every soul seeking to understand the depths of the human heart.

About the Author

Indlieb Farazi Saber

Indlieb Farazi Saber is a journalist and storyteller whose work crosses borders, weaving together culture, history and identity. Her work has appeared in TRT World and Al Jazeera English, among others, with one piece earning her a place as a finalist in Save the Children’s Global Media Awards.

Ivy Johnson

Ivy Johnson is an illustrator and cartoonist based in Queens, New York. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Toronto Star, The New York Times and MUBI Notebook.

You may also be interested in...

Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, a Conversation With Food Historian and Author Nawal Nasrallah

Arts

In Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, Arab food historian Nawal Nasrallah breathes new life into an anonymously compiled 13th-century cookbook.

Grand Egyptian Museum: Take a Tour of the New Home for Egyptian Artifacts

Arts

The Grand Egyptian Museum has officially opened its doors, revealing treasures from the ancient Egyptians and their storied past.

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.