Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.

Cartier Looked to Islamic Design To Create Striking Jewelry

An exquisite diamond and platinum bandeau is suspended in a glass case, sparkling as light hits it from different angles. A distinctive zigzag runs around the curve of the headband, punctuated by large diamonds, while spaces within the platinum form intricate patterns.

This regal headpiece was made in 1911 by the Cartier jewelry house. Described as an “oriental bandeau,” it draws inspiration from Islamic architecture and looks strikingly modern for its time.

The bandeau is on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London as part of a major Cartier exhibition of more than 350 pieces of jewelry and other decorative items. It is just one example of how the heirs to the jewelry house—Louis Cartier, along with his brothers Jacques and Pierre—looked to the Islamic world for inspiration as they sought to create new, modern jewelry in tune with the times.

Top: Department of Culture and Tourism—abu Dhabi/photo: Ismail Noor/seeing Things. Above: Alamy/Right Perspective Images

Top: Cartier’s “Oriental” bandeau from 1911 shares the zigzag pattern of its inspiration, the facade of the Mshatta Palace. Above: An eighth-century CE Jordanian desert castle now housed in the Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin.

“Louis Cartier was obviously fascinated by the art and culture of the region and had an extensive library containing virtually every major publication on Islamic art,” said lead exhibition curator Helen Molesworth, who is the senior jewelry curator of the Victoria and Albert Museum. “He was also a collector in his own right—Persian manuscripts, Mughal artifacts, Indian jewelry. Lots of dealers were putting on exhibitions of Islamic art in Paris and other European cities at the beginning of the 20th century, and we see these exhibition catalogs in Louis Cartier’s library.”

Established in 1847 by Louis-Francois Cartier, the business was inherited by his son, Alfred, later that century. In its early days, the House of Cartier, like other European jewelers, was inspired by 18th-century French decorative arts. This gave rise to the Garland Style, featuring bows, ribbons and wreaths.

By the dawn of the 20th century, these elaborate designs were beginning to feel old fashioned.

The Cartier brothers and their teams were very inspired by Islamic art.

Left: Francesca Cartier Brickell looks through old family photos. Right: Her great-grandfather Jacques Cartier meets with sheikhs in 1911 on a visit to the Arabian Gulf.

Left: Jonathan James Wilson; Right: Courtesy of Francesca Cartier Brickell

How did Islamic design inspire the Cartiers?

Cartier only became an internationally recognized brand after Louis and his brothers took over at the turn of the 20th century. While Louis stayed in Paris, Jacques was dispatched to London, and Pierre crossed the Atlantic to New York.

This new generation had global ambitions for the House of Cartier that would require innovation in design, materials and craftsmanship.

In 1911, Jacques Cartier, the gem expert, embarked on an expedition to the Middle East, India and Sri Lanka. What began as a simple, strategic buying trip turned into a voyage of discovery that would have a profound effect on Cartier’s design ethos.

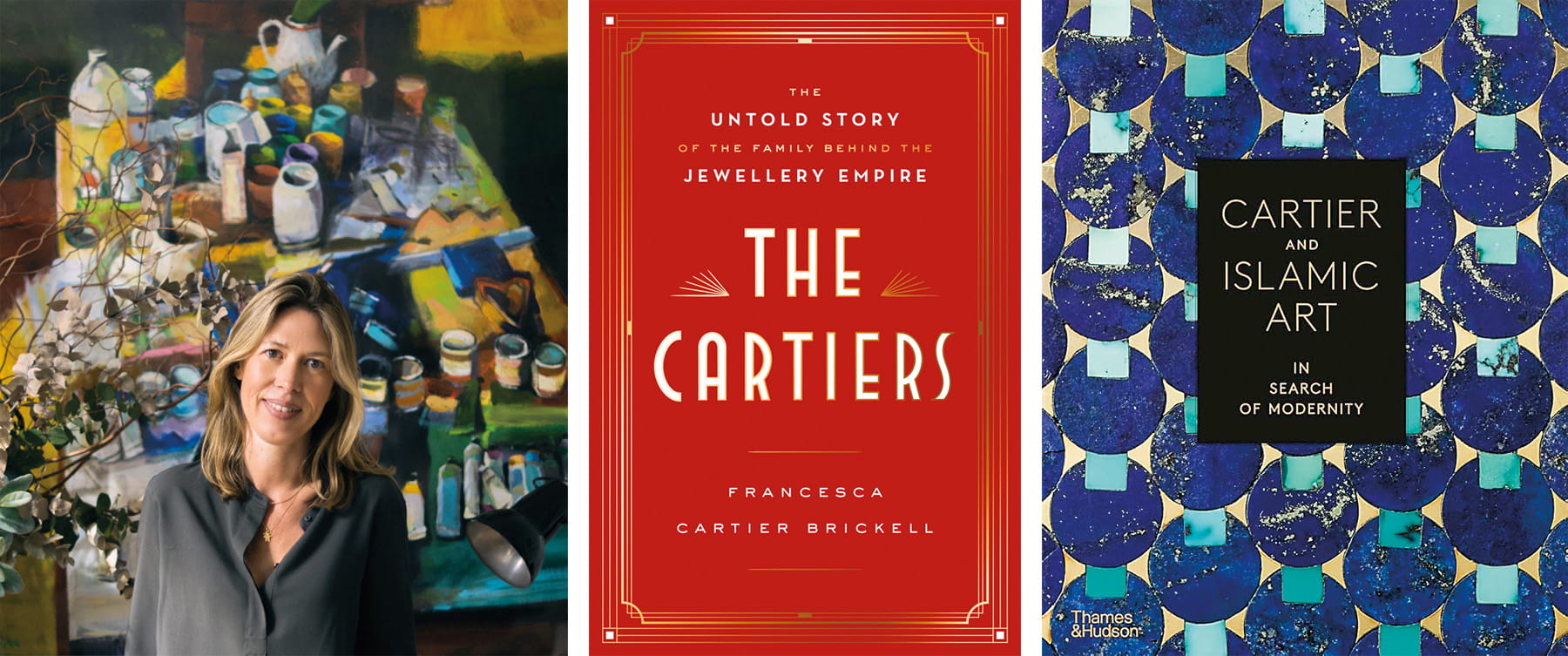

The great-granddaughter of Jacques Cartier, Francesca Cartier Brickell, spent more than a decade researching her family history, resulting in a book, The Cartiers. Her starting point was correspondence among the brothers that she uncovered in her grandfather’s cellar.

“The Cartier brothers and their teams were very inspired by Islamic art,” said Cartier Brickell. “During his travels in the Middle East in search of pearls, Jacques documented his fascination with the culture and surroundings in his diaries and photo albums. He had a deep appreciation for the artistry and craftsmanship he encountered.”

Cartier Brickell has spent years researching her family history and wrote one of two recent books on their life and work.

Jonathan James Wilson

In an office down a long corridor at the Louvre Museum in Paris, Judith Henon-Raynaud, the head curator of the Islamic arts department, turns the pages of a book she co-edited, Cartier and Islamic Art.

An image of the “oriental bandeau” made by Cartier in 1911 is published alongside a 1904 photograph of the facade of the Mshatta Palace, an eighth-century Jordanian desert castle, now housed in the Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin. The juxtaposition is striking and reveals the zigzag design that inspired this piece of jewelry.

“The Cartiers chose motifs which would translate into the language of jewelry,” said Henon-Raynaud. “Simple, stripped-back, geometric shapes that could be reproduced in platinum and diamonds—minimal color so that the shape really stood out. The geometry they found in Islamic art felt very modern at the time, and I think it still does today.”

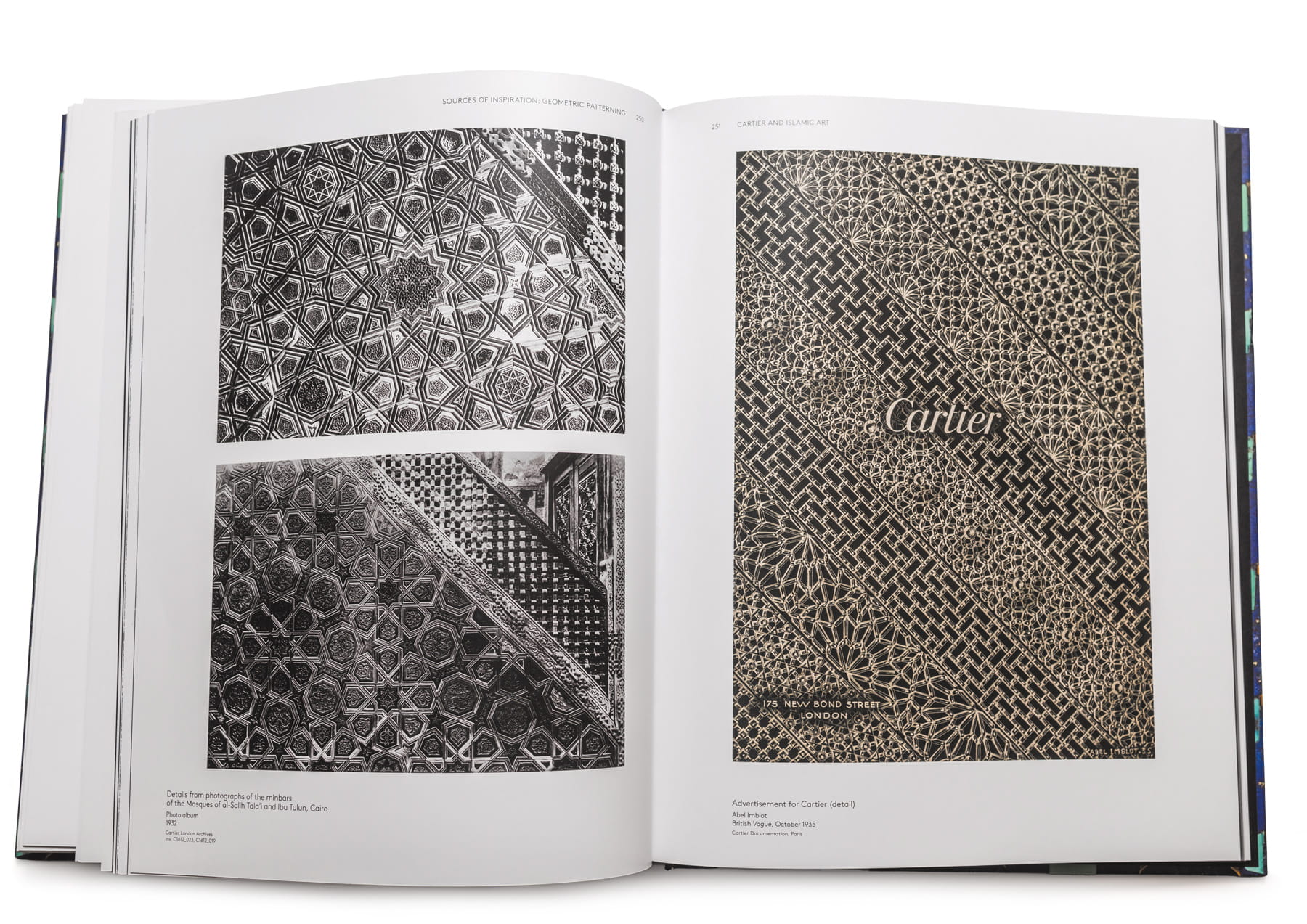

With its abstract geometry and repeated interlocking shapes, Islamic art and architecture opened up new design possibilities. Triangles, rectangles, hexagons and octagons offered limitless combinations while stars, scrolls, arches and arabesques also found their way into Cartier’s visual vocabulary.

Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity compares details from 1932 photographs of minbars of the Mosques of al-Salih Tala’i and ibn Tulun in Cairo, left, with a company advertisement in British Vogue from 1935, right.

Waleed Dashash

The Cartiers chose motifs which would translate into the language of jewelry. … The geometry they found in Islamic art felt very modern at the time, and I think it still does today.

A 1922 platinum bandeau, set with coral, onyx and tortoiseshell, recalls the horseshoe-shaped arches and colonnades of Islamic architecture, scaled down to a wearable size. The Cartier archives in Paris contain an illustration of strikingly similar arches at the Qalawun complex in Cairo, along with sketches based on this illustration by Charles Jacqueau, one of Cartier’s most important designers.

“You have to be able to think in three dimensions to turn something two-dimensional, like a hard stone inlay in a wall, into something that wraps around your wrist or your neck,” said Jennifer Tonkin, an expert in Cartier jewelry at Bonhams auction house in London.

“Geometric forms consist of distinctive shapes that can be repeated to form a pattern, and carved gemstones fit very neatly into these shapes. You can almost simulate what you are seeing in an Islamic building.”

The spaces between the precious metal and stones are as important as the jewels themselves, creating shapes in much the same way that a mashrabiya on a balcony sculpts the light that passes through the carved wood.

A scarab brooch, Cartier London, 1925, echoes the shapes and color palettes of the Islamic world.

Cartier

The structural symmetry of Islamic buildings, like the Alhambra Palace in Andalusia, informed Cartier’s use of clean lines. A new design lexicon was taking shape—Art Deco—which would dominate all forms of Western decorative art in the 1920s and ’30s.

The art of ancient Egypt was also in vogue, following the excavation in 1922 of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Motifs such as pyramids, sunbursts and papyrus flowers fed into the Art Deco movement. Cartier produced a number of ancient Egyptian-inspired objects, some of which involved mounting historical fragments, known as apprêts, into modern settings.

“Jacques Cartier was fascinated by ancient Egypt,” said Cartier Brickell. “His extensive library has many well-thumbed, annotated books on the subject. Ancient Egyptian faïences, picked up in antique shops and on his travels in Egypt, became the centerpieces of one-of-a-kind brooches.”

Not only did Cartier draw on the shapes of the Islamic world but also its color palette. Illustrations of tiled panels from mosques in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, with their vibrant blues, greens and turquoises, can be found in the Cartier archives in Paris. Echoes of these designs appear in a 1922 buckle brooch, set with an octagonal emerald surrounded by sapphires and diamonds, and a 1923 pendant, composed of two carved emeralds and a cabochon sapphire.

On display at the Victoria and Albert Museum are ceramic items from Iznik, Türkiye, dating to ca. 1580, a dish, left, with a blue leaf in the Saz style of that era of the Ottoman Empire, and a jug with a scale pattern, middle, that show a clear influence on a vanity case, right, issued by Cartier Paris in 1927.

Left to Right: Department of Culture and Tourism—abu Dhabi/photo: Ismail Noor/seeing Things

The Islamic-inspired objects … set a benchmark for a level of reverence that needed to be given to everything [in the exhibition].

“The Cartiers juxtaposed turquoise with lapis lazuli and emeralds with sapphires,” said Henon-Raynaud of the Louvre. “These were color combinations that you would not see in the West at that time. Indeed, wearing blue with green was considered the height of bad taste.”

Jacques Cartier’s travels in India inspired some of Cartier’s most colorful and famous designs. The 1920s “Tutti Frutti” line, with its rubies, emeralds and sapphires, mimics the floral extravagance of Mughal jewelry.

“Jacques was deeply struck by India,” said Cartier Brickell. “He wrote about being overwhelmed by the ‘blaze of color’ under the Indian sun. But the influence extended beyond color: Indian jewelry traditions inspired Cartier’s creativity in form and scale.”

Art Deco peaked in the 1930s before going into decline, but Islamic art has continued to inform Cartier’s creations to the present day. In 1947, Cartier designed a necklace called the “Arabic Sautoir” composed of gold beads accented with knot motifs. It continued to be produced until the 1970s as the “Muslim Prayer Bead” necklace.

Cartier’s “Tutti Frutti” pieces were inspired by Jacques Cartier’s travels to India and pay tribute to Mughal extravagance.

Jonathan James Wilson

Cartier exhibition at Victoria and Albert

The overall design of the Cartier exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum is the work of Asif Khan, a London-based architect and multidisciplinary artist. From conception to completion, he spent 18 months choreographing the show, which included creating soundscapes and making clouds from water vapor.

“In a jewelry exhibition, objects are behind glass, so it’s difficult to get a sense of the narrative unless you have a curator talking you through,” said Khan. “We also need to think about the relationship that jewelry has with the wearer. These objects are worn on the skin; they have a certain weight and texture. So in the absence of touch, I thought the exhibition needed to trigger our other senses to allow the objects to speak through the glass and almost breathe on us.”

Beyond the famous brand name, Khan knew little of the history of Cartier when he started work on the exhibition. As with all his projects, he looked for a personal connection that would give the work individual meaning to him.

London-based architect and multidisciplinary artist Asif Khan designed 2025’s Cartier show at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Courtesy Asif Khan Studio

“The Islamic-inspired objects were my way in,” said Khan. “I felt I had to communicate their importance to everyone who visited. I didn’t hold those objects above others, but they set a benchmark for a level of reverence that needed to be given to everything.”

In the final room of the exhibition, there is a dazzling display of tiaras, presented like a debutante’s ball and accompanied by Shostakovich’s Second Piano Concerto.

A 1914 platinum, diamond and pearl tiara has a central tree-of-life design made of black onyx. Alongside it sits a tiara created more than a century later. Composed of Cartier’s distinctive “Tutti Frutti” jewels, the design is once again based on the tree of life.

“One of the brilliant things that Cartier has done is to constantly reinvent and come up with new ideas,” said Molesworth, the curator. “But there is always a nod to heritage. This 2018 tiara has a Russian shape, Indian-type stones and an Egyptian-style tree of life. If that is not a brilliant reuse of contemporary design, I don’t know what else is.”

You may also be interested in...

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.

History in Objects: 12th-Century Glass Flask an Islamic Golden Age Masterpiece

History

Arts

Golden Vessel From the Islamic Golden Age Reflects Cross-cultural Connections

Restoration Uncovers Beauty of Georgia’s Hidden Wooden Mosques

Arts

Until recently few outsiders knew the wooden mosques dotting the highlands of Georgia existed, leaving many of them to deteriorate. The rediscovery of the architectural gems has sparked a movement for their preservation.