Cairo Hums Her Name: The Eternal Voice of Umm Kulthum

The late singer known as Kawkab al-Sharq—the Star of the East—was a national treasure of Egypt who lives in history books, diasporic memory and musical reinvention.

6 min

Written by Banning Eyre

Ibrahim Maalouf still remembers the silver key slotted into the wooden cabinet, tempting him to turn it. Behind the glass doors lay the complete recordings of Umm Kulthum, Egypt’s greatest singer, a treasure he was forbidden to touch.

Now a celebrated Lebanese French trumpeter and composer, Maalouf grew up hearing her voice as a constant presence in the house. “She’s the voice I’ve listened to the most in my life,” he says. “Even when I was a baby.”

For many Umm Kulthum remains unmatched. She is Cairo itself. The city hums with her presence, her voice drifting through cafés, taxis and wedding venues. The national treasure lives in the pages of Egypt’s history books, diasporic memory and musical reinvention—but half a century after her death, how she is remembered mostly depends on who is listening, and where.

Trumpeter and composer Ibrahim Maalouf grew up hearing Umm Kulthum’s voice as a constant presence in his family’s home.

Yann Orhan

Adam Mekiwi, an Egyptian journalist and coproducer of the 2015 documentary “Oum Kalthoum, la Voix du Caire,” recalls growing up in Alexandria with her voice in the air and her legend in family stories. “My grandmother would always tell me about the concerts she would frequent in the ’50s and ’60s with my late grandfather, and how all the aristocracy and bourgeoisie attended, dressed to the nines,” he says.

Her music, of course, wasn’t just for the elite but for everyone: the bus driver, the housewife, the men and women working the fields. It was this extraordinary reach, Mekiwi adds, that earned Umm Kulthum, whose name is transliterated various ways, the title Kawkab al-Sharq—the Star of the East—a voice that shone across classes, cities and borders alike.

Others experienced her voice at a distance. Ken Habib, an ethnomusicologist, composer and performer on oud and guitar, first encountered her music as a child in the US, hearing an ensemble perform her songs at parties.

Growing up steeped in Arab culture, he was struck by the sound but didn’t yet understand its weight. Years later, when he delved into musicological studies, he began to recognize her unique contribution to Arabic music. Now a professor of music at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, Habib reflects: “She was on a different level, hitting harder than almost everybody else in the field.”

Music anthropologist Sophie Frankford says today’s popular ensembles performing shaabi—a traditional Egyptian folk-music genre—sometimes play “shaabified” versions of Umm Kulthum songs.

Courtesy of Sophie Frankford

An inspiration is born

To understand why she continues to inspire such devotion, it helps to recall the woman herself.

Born Fatima Beltagi in 1904 to a poor family in Egypt’s Nile Delta, she learned Qur’anic recitation from an early age, her voice trained in precision, breath control and subtle ornamentation. Touring with her musician father as a child, she absorbed the rhythms and melodies of local folk songs, an apprenticeship that laid the foundation for a career that would expand over five decades.

By the 1930s, Umm Kulthum, her adopted stage name, had become the most celebrated singer in the Arab world. Her monthly radio concerts drew listeners from every corner of Egypt and across the region. Families paused their evenings, cafés fell silent, and audiences were carried into tarab—a state of musical ecstasy she was uniquely able to summon.

Her voice, expansive and precise, could stretch a single note across several beats, bend microtones with exacting subtlety and fold emotion into every melodic twist.

For Maalouf, who as a child gazed at the near-sacred Umm Kulthum records locked away in his family’s cabinet, that mastery remains an education in itself. Decades later, trained by his father in the maqamat (Arabic musical modes), Maalouf came to fully appreciate the subtle harmonies and ornamentation that underpin her songs.

In 2015, he released “Kalthoum,” a jazz interpretation of her masterpiece “Alf Leila Wa Leila” (A Thousand and One Nights). The challenge was immense: how to preserve the sweeping emotional arcs and improvisational richness of her original while using jazz instrumentation and phrasing.

“I wanted to show thattarab and all those maqams and songs that we consider as being very Arab are not so different from jazz,” Maalouf explains.

But he would encounter resistance from his Arab music peers, who felt that Umm Kulthum was sacred, almost untouchable.

His jazz colleagues were also skeptical. They told him that Arabic music does not swing. “I used to explain to them, ‘It does swing. It just does not swing the way you think swing is.’ So I said, ‘OK, I’m going to take an Umm Kulthum song, the most loved Arab music in the Arab world, and I’m going to show you that it is jazz. I’m just going to dress it differently.'”

When he performed the piece at Lincoln Center in New York, one Arab listener began singing along, annoying some in the audience. But not Maalouf. “I was ecstatically happy because this guy was showing the crowd how parallel the musics were.”

A sculpture of Umm Kulthum is displayed at Aisha Fahmy Palace in Cairo, which hosts an exhibition dedicated to the famed singer till mid-November 2025.

Saleh Al-Amer

The genius of the voice

If Maalouf’s jazz experiment shows how Umm Kulthum’s music can leap genres and continents, scholars and performers closer to her tradition stress why her artistry remains unrivaled.

Habib points to her rare combination of technical mastery and emotional depth. She could expand a single verse into a 45-minute performance without losing momentum. “It’s difficult, weighty music, heavy stuff,” he explains. “But as you internalize the music, you start to explore new depths and hear new things.”

From the late 1920s until her final concert in 1973, Umm Kulthum performed and recorded more than 300 songs. Beginning in 1934, she staged monthly radio concerts known to bring all activity to a halt, not just in Egypt but throughout the region. Her vocal improvisations brought live audiences to tears and roaring approval.

As a musician first approaching Umm Kulthum’s music, Habib was captivated by its beauty but daunted by its complexity. He challenged himself to perform her repertoire with both a takht—the small chamber ensemble of oud, qanun, violin and riqq (a type of tambourine) that accompanied Umm Kulthum when she was starting her career in the 1920s—and also with full orchestras of up to 40 musicians, the kind that filled Cairo’s airwaves during her legendary broadcasts.

Her ability to hold audiences in suspense and then release them into ecstasy was central to tarab—the very state of musical rapture that Maalouf recalls when describing her influence. Audiences responded audibly, urging her on with shouts of approval, sighs and tears, becoming part of the performance itself.

Unlike Lebanon’s Fairuz—her only true musical peer—who worked almost exclusively with her trusted composers Elias and Mansour Rahbani, Umm Kulthum drew from a highly competitive stable of Egypt’s top composers and poets, all eager to work with her. Her favored collaborators included Muhammad al-Qasabji, Riyad al-Sunbati, Ahmad Shawqi, Zakariyya Ahmad, Mahmud Bayram al-Tunisi and Muhammad Abd al-Wahhab, one of Egypt’s most innovative and progressive composers of the century. “She could afford to be selective,” says Habib. “And when you composed for her, you got to really show your stuff as a composer.”

Her rise was inseparable from her times. By the mid-20th century, radio had filtered across Arab society, amplifying Umm Kulthum’s reach. She also found a second life through the golden age of Egyptian cinema, starring in several films that broadcast her voice to an even wider audience.

“She represented something very traditional in Egypt on a larger stage,” Habib adds. “She was epic. There isn’t anybody today who has that kind of appeal across the sociological spectrum.”

Virginia Danielson, author of The Voice of Egypt, a 1997 biography of Umm Kulthum that continues to sell well today, described the singer as possessing the musical chops of Ella Fitzgerald, the public persona of Eleanor Roosevelt and the popularity of Elvis Presley.

Since Danielson’s biography, more than 60 books have followed, each probing a different facet of Umm Kulthum’s life and influence. Her presence endures not only in scholarship but also in public memory: In Cairo the permanent museum at Manasterly Palace traces her story through her clothing, jewelry and instruments, while the “Voice of Egypt” exhibition at Aisha Fahmy Palace celebrates her through paintings, photographs and sculpture.

While her iconic image fills museum halls, Cairo’s streets pulse with new sounds. The rise of electro-shaabi, or mahraganat, has given a platform to DJs who might never attempt an Umm Kulthum song yet still inherit her spirit of reinvention.

Umm Kulthum’s well-known song “Hajartak” has been popular since she first performed it in 1959.

Saleh Al-Amer

Shaabi and shifting attitudes

Shaabi music, literally meaning “of the people,” started to emerge from working-class neighborhoods in Cairo in the 1920s. With driving rhythms and earthy lyrics, it has long been the soundtrack of weddings and street celebrations, but even here, Umm Kulthum’s shadow looms, her songs forming a reference point for performers and audiences alike.

Sherifa Zuhur, a historian of Egypt’s music and society and director of the Institute of Middle Eastern, Islamic and Strategic Studies in Los Angeles, notes “it all depends on the venue.” Weddings were long the most important stage forshaabi musicians, yet over time, some gatherings became more constrained, and live performers grew less common.

“The wedding parties became segregated. Some of them stopped hiring musicians at all. So the real wedding musicians, the ones who could play what people request all night long, have dwindled.”

Shaabi singers draw inspiration from her work, adjusting tempo and rhythm to suit modern audiences, but performing her songs requires mastery. In earlier decades deeply attentive listeners—the sammi’ah, as A.J. Racy, a professor of ethnomusicology at the University of California, described them—would propel tarab performances with perfectly timed, audible reactions.

Such connoisseurs still exist, though in far smaller numbers today, highlighting both Umm Kulthum’s enduring presence and the changing landscape of live music in Cairo.

Sophie Frankford, an anthropologist of music at King’s College, London, observes how her songs are adapted, transformed and sometimes deliberately reimagined. Her current research focuses on rethinking music and modernity in the Middle East, particularly Egypt. She notes that popular shaabi ensembles performing at weddings and public celebrations sometimes play “shaabified” versions of Umm Kulthum songs.

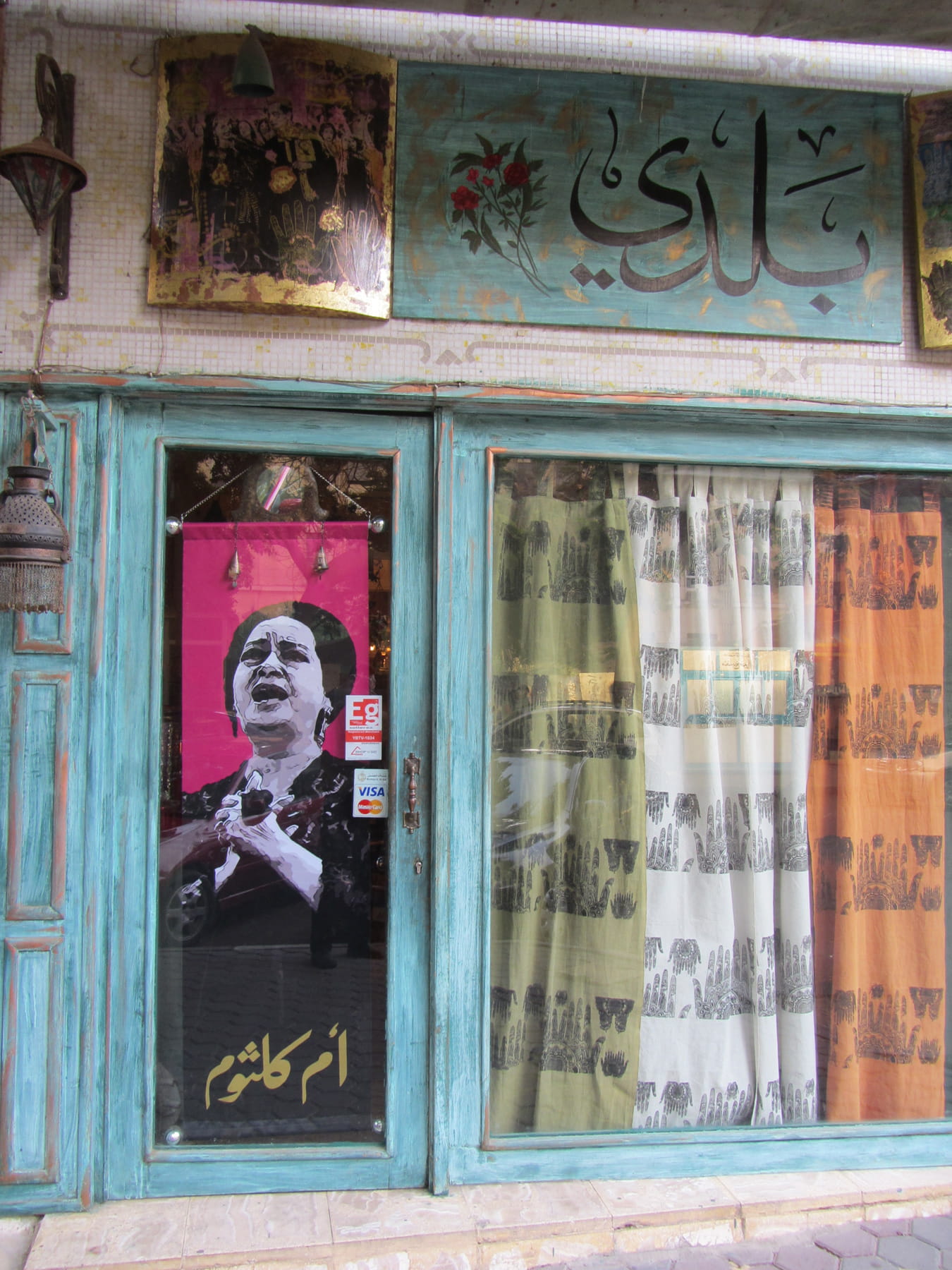

A high-end art shop in Cairo displays a poster of Umm Kulthum on its door.

Banning Eyre

“They will play it a bit faster or play it with a heavy maqsoum beat behind it.” Shaabi star Mahmoud al-Leithy quotes Umm Kulthum in his song “Atawi,” which has racked up millions of views on YouTube, in part thanks to a playfully dramatic video.

As musicians continue to explore alternatives, Umm Kulthum’s presence remains a central reference point. Her melodies, phrasing and the emotional intensity of her performances still shape musicians’ approach—whether they reinterpret it, accelerate it for shaabiaudiences or deliberately move away from it to explore other voices.

Despite these modern takes on Umm Kulthum’s music, Fayrouz Karawya, a Cairo-based musician and scholar, insists an appreciation of the diva’s music is something one must grow into, but once it hits, it never leaves.

“We Egyptians have a long-standing conviction that you start to love Umm Kulthum after passing your adolescence,” she says. “You grow up, you fall in love. You hear her in taxis every night at 11 p.m. The songs keep accruing new meanings. Then you travel, and when you come back, you hear her voice and you know you’re home.”

More From AramcoWorld

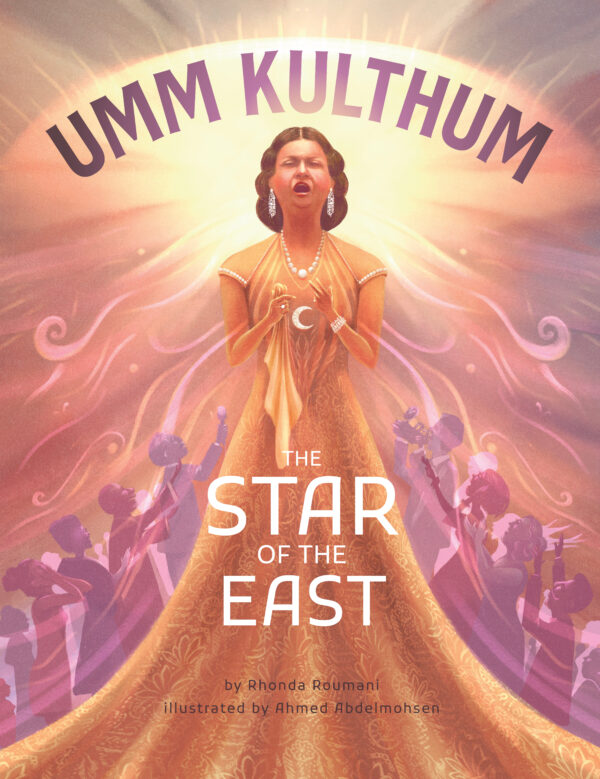

Introduce Young Readers to the Star of the East

Want to share Umm Kulthum's story with the next generation? Rhonda Roumani's beautifully illustrated children's book brings the singer's early life and timeless spirit to life for young readers.

Read the review here.You may also be interested in...

Othman Almulla Embodies Arab World’s Dream of a Golf Championship

Culture

The journey of Saudi Arabia's first professional golfer parallels that of the region from humble beginnings to leaderboard for the global game.

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.

Spotlight on Photography: Drinking in Türkiye’s Coffee Culture

Arts