Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.

From a studio overlooking the foothills of the Zailiysky Alatau Range near Almaty, Kazakhstan, three women are quietly working on their next piece of a blanket made in kurak, a traditional Kazakh patchwork technique. They are apprentices of a kurak master and founder of a school dedicated to helping this style of art to rebound.

Gulmira Ualikhan pulls out kurak after kurak—pieces of quilt, once present in almost every household in the country—prompting compliments for the women who crafted them from rare fabrics passed along the old caravan trails of the Silk Road. It had both practical use as home décor and as part of a woman's dowry, and symbolic power as protection.

Seeing the toll time and globalization took on the craft, Ualikhan is now slowly reviving the kurak technique, which involves patching together fragments of small textiles in an orderly pattern to form a block. The work fits in with a rising global demand for hand-crafted textiles, inspiring her to reinvent the craft beyond Kazakh patterns.

Ualikhan (in red) runs a school and workshop for her students in Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Kurak elements in Kazakh culture

Although patchwork is found globally, Kazakhs know it as a common decorative art form. Kurak is used in blankets and pillows, carpets and clothing.

Ualikhan has spent years researching traditional patterns found in museum collections, old photographs and historical illustrations. Now she applies those patterns in her craft.

"This is shi-kurak, the Kazakh block," says Ualikhan, pointing at a square block that resembles a well. "All over the world, everyone considers it their own, and it's because it is a fundamental block. Probably because it's simple and easy for everyone to understand. In Kazakh it comes from the word shi, meaning 'thin.' The Russians call it a well."

With symbolic messages woven into the design, every kurak piece holds some of the artisan’s story, thoughts and wishes.

Left: Gulmira Ualikhan shows kurak pieces at her workshop. Right: Kurak employs measured, straight blocks of geometric patterns.

Ualikhan explains the cultural symbolism and beliefs behind each quintessentially Kazakh kurak motif. Over the years, the geometric patterns earned evocative names: ram's horn, tree of life, axe, pair of earrings, a wave. One of them is a tumar—an amulet.

"In the past people used to make tumars in the shape of triangles and place inside them verses like Ayat Al Kursi [known as the Throne Verse] or other surahs from the Qur'an. Of course, nowadays, when we sew, we don't actually stitch those verses into the fabric. But symbolically, we still call it a tumar, an amulet," says Ualikhan.

Kurak blankets are a common dowry item, with symbolic messages woven into their design. One such blanket carries blessings for a family: a tree-of-life pattern to denote prosperity, the rhombus for fertility, triangles for spiritual and physical strength, and zoomorphic and nature-inspired patterns like koshkar-muiiz (ram's horns) to represent masculinity.

Every kurak piece holds some of the artisan's story, thoughts and wishes.

"Each of my creations is not just a blanket. It carries the history of my family stitched by the warmth of my hands, the inspiration from great masters and the support of my loved ones," says Maira Ramazanova, one of Ualikhan's students.

A variety of kurak patterns go into blankets, home décor and more.

Ualikhan echoes the sentiment: "When I sew, I say: 'I'm stitching my prayer into this piece; may the person or family who receives this quilt be blessed.'"

Along with creating her own patterns, Ualikhan incorporates motifs inspired by cultures around the world. The patchwork technique spread as far as Japan, Europe and the US.

"The Japanese are considered one of the strongest kurak masters. Their technique is defined by delicate handcrafted details that reflect a distinctly Japanese touch, and soft, vintage tones. In contrast, Russian fabrics are bright and rustic, filled with polka dots and florals. Kyrgyz designs use bold black, white and red tones, sharp angles and tiny kurak patterns. Classic American style, on the other hand, is marked by large blocks and repetitive patterns, offering a sense of structure and simplicity," explains Ualikhan.

In the US, the International Quilt Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska, boasts a large public quilt collection from over 60 countries to satisfy anyone's appetite for color and exuberant detail in patchwork. One can find the black-and-red kuraks from Kyrgyzstan and the soft-toned Japanese pieces Ualikhan mentions, along with quilts from South Asia, China and France, to name a few.

Kurak patterns are woven into everyday life in Almaty, including the walls and floor of a metro station,

Textile history in Kazakhstan

According to Azhar Altynsaqa, textile artist and researcher, archeological finds of fabric remnants and needles made of bone suggest that textile traditions have existed across Kazakhstan as far back as the Botai culture from the fourth millennium BCE. However, surviving kurak pieces mostly date from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

Since then, Kazakhs have lost 60% to 70% of their traditional crafts, says Altynsaqa, citing Russian and later Soviet colonization as key causes, alongside the shift from nomadic to stationary life and changing tastes under foreign influence.

"Even before the [Russian] revolution, sewing machines, factory-made fabrics, aniline dyes and many other goods began to enter the Kazakh market, with the bulk coming from Russia," says Altynsaqa. "All of these items were fashionable and colorful. People began to buy more and produce less themselves."

In the past 10 years, Altynsaqa has observed a revival of traditional art, including kurak, as more artisans emerge "producing modern items using traditional methods, or vice versa, traditional items using modern techniques."

Kazakh textiles date to the fourth millennium BCE, but surviving kurak pieces are mostly from the 18th-20th centuries.

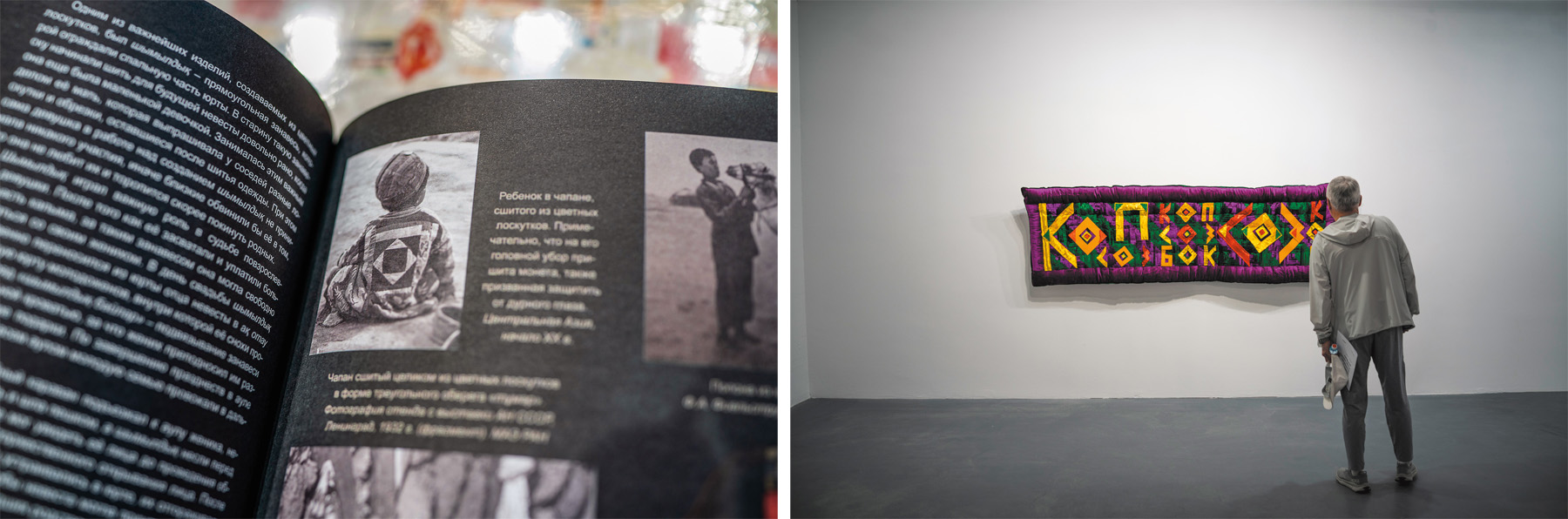

Left, a bookstore selling Erily Ospanuly’s Ethnographic Atlas of Kazakh Ornament and, right, “Köp söz bok söz” by artist Munar Abdukakharov, on display at Aspan Gallery.

Patchwork as therapy

In her studio, behind a desk laden with brightly colored blankets, Ualikhan describes how she tries to restore the value of the patchwork tradition.

"My mission, first and foremost, is to research the blocks, then to re-create those blocks in kurak technique and then to pass this knowledge to as many people as possible," Ualikhan says.

She had a successful career in finance, but after a personal loss, Ualikhan realized stress had taken a toll on her health. Once she gave up her job, the patchwork became a form of meditation. "It turns out that kurak is a therapy. I realized it later. What I was like back then and who I am now are two different people," she says.

Left: Household items made with kurak hold significant cultural value. Right: A student carries a kurak quilt.

A solitary sewer finds herself between art and craft. "When someone sews kurak, they're alone with themselves. No one is tugging them. They are structuring here, trying to sew even blocks," says Ualikhan. "And in that process, they learn to navigate and structure situations in life."

Ualikhan went on to open a school that teaches women, including those from underprivileged societies in Kazakhstan, in kurak technique. She teaches the patterns—passed down from mother to daughter—to modern women who are eager to take up the work of their foremothers.

Her student Ramazanova recalls the deep inspiration she felt watching every piece of fabric in her hands become a living symbol of tradition. "At that moment, I decided to continue preserving and passing on to future generations a value that is close to the heart of every Kazakh."

For another of her students, Oral Idelkankyzy, learning kurak has brought a sense of pride. "How happy I was when I managed to complete the simplest blocks! These small victories restored my confidence, my anxieties faded away, and my chaotic thoughts disappeared."

I decided to continue preserving and passing on to future generations a value that is close to the heart of every Kazakh.

Vendors sell kurak kurpe—traditional quilted blankets, mattresses and other goods—at Arlan Bazaar in Almaty.

Kurak's influence on modern jewelry design

Rising desire for handcrafted items has brought a parallel increase in the number of artisans exploring conventional materials and techniques. Manshuk Yesdaulet, a Kazakh artisan specializing in employing kurak technique by hand, is doing her bit via jewelry design.

She taught economics at universities, but once she went on maternity leave, Yesdaulet wanted to contribute to the family without a full-time commitment. So, a decade ago she turned her interests into a career that is reshaping what kurak can be.

"As Kazakhs, we all love gold, silver or at least something semiprecious," Yesdaulet says. "But then I realized my audience is girls who are bold, progressive and a little extravagant—those who are not afraid to look the way they want."

Her amulets, brooches and bracelets embrace vivid colors. Though she mostly sews them in the traditional form of a well, they rather resemble a budding flower or an eye.

Each nation has similar ornaments. ... It feels like our essence is the same.

Artisan Manshuk Yesdaulet specializes in employing conventional kurak materials and techniques to create amulets, brooches and bracelets in vivid colors.

Kurak perfectly expresses the idea of making beautiful products from limited resources, Yesdaulet says.

"Back in the days of the Silk Road … fabric was considered a wealth, a treasure—a true luxury," she says. Even traditional garments like Russian shirts or a Kyrgyz koinok (traditional shirt) show that women made use of every part of the fabric. "It was considered a sin to waste fabric," she adds.

Now mass production poses a threat, Yesdaulet says.

"Kurak is meant to be made by skilled artisans who understand that traditionally it was created from leftover fabric," says Yesdaulet, "not from brand-new, store-bought red, yellow or blue cloth that's cut up just for the sake of it."

In 2024 Yesdaulet moved to Palo Alto, California, in the US with her family. Initially she felt lost in a new environment. The soothing nature of hand-sewing kurak lifted her spirits.

Ualikhan’s studio overlooks the foothills of the Zailiysky Alatau Range in Kazakhstan.

"I was doing the one thing I knew how to do, and it helped me get through that time. Now, I want to continue running workshops here or maybe try selling on local marketplaces. I'm not giving up. I want to grow here too, as an artist and a craftswoman," says Yesdaulet.

Kurak across continents

Living in the US' multicultural society, Yesdaulet finds kurak even more relevant, as she puts together pieces from different cultures. Each piece of cloth carries its own story, and when put together, something uniquely beautiful comes forth.

"Actually, I see these techniques in every nation, which is interesting. Each nation has similar ornaments, with maybe a bit of variation or a different reading," Yesdaulet says. "It feels like our essence is the same."

Our children will bring their own worldview and find new ways to weave kurak into their world.

Across the globe in Kazakhstan, Ualikhan shares Yesdaulet's vision of unity rooted in one fundamental block. To her, each kurak reflects the continuity of a collective heritage.

"We must teach the basic blocks of kurak to the next generation. Our children will bring their own worldview and find new ways to weave kurak into their world, taking the tradition to new heights," she says. "But it all begins with the shared foundation we all start from."

More From AramcoWorld

From Kurak to Curated Gold

About the Author

Aibarshyn Akhmetkali

Aibarshyn Akhmetkali is a contributing writer to AramcoWorld based in Astana, Kazakhstan. Her work mainly focuses on the culture, history and arts of Central Asia.

Danil Usmanov

Danil Usmanov is a documentary photographer dedicated to capturing the untold stories of Central Asia. His work has been featured in The Guardian, Die Zeit, Meduza, Le Monde, New Lines Magazine and Der Spiegel.

You may also be interested in...

Ramadan Nostalgia Requires Active Reconstruction

Arts

Artists demonstrate how Ramadan traditions endure through deliberate acts of memory and care.

Meet Sculptor Marie Khouri, Who Turns Arabic Calligraphy Into 3D Art

Arts

Vancouver-based artist Marie Khouri turns Arabic calligraphy into a 3D examination of love in Baheb, on view at the Arab World Institute in Paris.

FirstLook: Poetic Fusion

Arts

Prior to our modern practice of image manipulation with editing software, photographers worked more with planned intention and craft.