Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.

On a semiresidential street in Karachi, behind the gates of an elegant family home, a revolution in cultural preservation is quietly taking shape. Pakistan, a land known for its diversity of textiles across regions, from the mirrorwork of Sindh to the muted weaves of Balochistan and the fetching phulkari embroidery of Punjab, now has a textile museum to call its own.

And at the heart of this labor of love is Nasreen Askari: curator, collector and custodian of stories stitched into cloth. The museum is called Nasreen ki Haveli, built in the home she shares with her husband, Hasan Askari. It opened its doors in December 2024.

Nasreen’s journey as a textile enthusiast began in a hospital ward in Jamshoro where, as a young medical student, she first encountered the profound symbolism of Sindhi textiles.

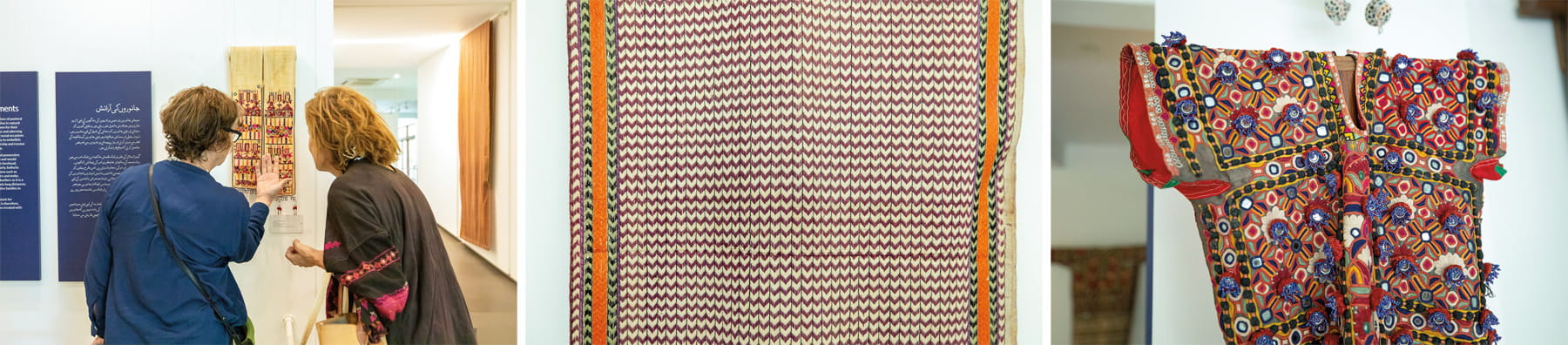

Top: The vibrant textile legacy of minority communities in Pakistan’s southeastern province of Sindh are among those on display at Nasreen ki Haveli in Karachi. Above: Also highlighted is a bujhki, or traditional dowry purse, bearing intricate embroidery and mirror work.

“In Jamshoro, we’d see patients from all over Sindh,” she recalls. “The women who came wore the most striking, almost arresting garments. Colorful, embroidered, printed, quilted—every single textile art was visible. Their garments were their identities.”

This wasn’t a fleeting curiosity. For Nasreen it was a revelation. “You had to look at a woman’s chadar, at her blouse front, to know whether she was from the mountainous west of Sindh or from the plains or from the delta,” she says.

One encounter in 1972 left an indelible mark. A Khosa Baloch woman, from the west of Sindh, handed Nasreen a red handkerchief, delicately embroidered with flowers—black for her sons and red for her daughters. One black flower represented her son who was dying of cancer. “She intended to unravel it after his passing and replace it with a new flower when God would give her another son,” Nasreen remembers. “I still have that handkerchief.” It is the piece that started her collection.

Colorful, embroidered, printed, quilted—every single textile art was visible. Their garments were their identities.

Left: The museum is the brainchild of Nasreen Askari. Right: Hasan Askari, her husband and the cocurator, says Nasreen ki Haveli’s mission is “to preserve, protect, conserve, document and display Pakistan’s textile heritage.”

Geography influences design

Z.T. Bilal, a Lahore-based design educator and researcher, explains textiles’ design language is deeply local. “Folk textiles are spontaneous expressions of the artisan’s environment. That’s where their design sense comes from—the balance of color, the textures, the composition. It’s embedded in their way of life.”

Bilal recalls an exhibition at Karachi’s Mohatta Palace Museum, of which Nasreen has served as a director since its 1999 founding, that brought textiles into geographic context. “It was like walking through Pakistan.”

That regional specificity and history are exactly what Nasreen ki Haveli seeks to preserve.

Nasreen’s commitment to cultural preservation is deeply personal, rooted in her lived experience as a doctor in training.

Left: The home that boasts the museum was designed by Habib Fida Ali, a pioneer of modernist architecture in Karachi. Right: A display notes that textile adornments are also for prized animals, including camels.

Despite pursuing a career in medicine after qualifying as a doctor, including postgraduate studies in England, where she met her husband, her love for textiles endured. On a return trip to Pakistan, she joined a friend working in Sindh’s cultural department on a field visit. That trip cemented her calling.

She would later work on a project at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, laying the groundwork for a career in textile curation. “I was very unfit for the task,” she says modestly, “but in those days it was easy for somebody off the street to express rabid interest in a particular item and be allowed to handle it.”

The couple began collecting seriously, eventually amassing 800 to 1,000 pieces. These cultural artifacts were obtained directly from the communities that made and wore them. “It was a very slow accretion,” Nasreen says. “Some women sold them to me, others gave them.”

Hasan Askari, her partner in life and curation, adds, “There are lots of people who collect textiles, but Nasreen fostered relations with these women. She names villages instead of the wider region. That was unique then and still is.”

What’s in the Nasreen ki Haveli museum?

The oldest piece in the collection is a mid-19th-century lungi, a handwoven fabric traditionally worn in Sindh as a shawl or turban. “It has gold-wrapped thread with cobalt blue, red and white details. In Sindh, if you want to give a gentleman the ultimate accolade, you give him a lungi.”

Nasreen’s intimate knowledge of these pieces goes far beyond esthetics. Her fieldwork traced the roots of embroidery styles and weaving techniques to specific communities and villages. “Sindhi embroidery is about the best in the world,” she says with pride.

The collection ranges from traditional dowry purses called bujhkis decorated in the pakkoh style of embroidery to the Meghwar community’s late-19th-century parha (skirt) made from resist-printed handloomed cotton with embroidery and mirror work.

In the museum’s display from Sindh, a Rabari woolen shawl with yellow embroidery takes center stage. “Even though they live in hot climates, they wear wool,” Nasreen explains. “Their leader was killed one winter centuries ago, so they went into mourning wearing black wool and have continued to wear it ever since.

Left: Visitors are able to get close to Nasreen ki Haveli’s items. Middle: A lungi, or sashlike cloth worn by men in Sindh and Balochistan and popular during the Talpur dynasty (1783-1842), is on display. Right: “The Coat of Many Colours” exhibition includes this embroidered Sindhi outfit.

“It is a very rustic piece that is close to my heart. The shawl is a very dark brown, almost black. It has three different adornments—it is tie-dyed, it has a woven pattern on its borders, and it’s also embroidered with the yellow mimosa flower, the flower of the desert,” she adds.

The Askaris had long discussed how best to preserve these precious pieces. “If we were to ask our children to take these, they will gladly take five pieces each. They don’t have the means or the space to accommodate the collection. So what choice did we then have?” Hasan says.

Giving it to an international museum meant the pieces would rarely be seen. Donating locally seemed risky. “We could’ve sold them,” he says, “but some decorator would cut them up to make cushions. We didn’t want that.”

The idea of a museum is recent. “We decided to open a museum as a gift for the city of our birth,” Nasreen says. So, they transformed the home her parents built in 1966. “It occupies the ground floor and we live on the first floor; it is not such an imposition. It’s a very happy marriage,” she laughs.

Textile museum turns family home into public haven

Architect Ali Alam remembers the call vividly. “Hasan Askari cold-called me and explained the vision. We were in from the get-go.”

Alam, who runs a small design studio in Karachi, had never designed a museum. But he was struck by the opportunity and the responsibility. “It’s not just any house,” he explains. “It’s one of Habib Fida Ali’s first projects, one of the pioneers of the modernist movement in Karachi. … So as an architect, I had to keep my ego in check.”

Alam knew the home’s architectural legacy couldn’t be compromised, but the needs of the museum were unique. “The biggest challenge was the amount of display needed for this museum,” he explains, “because the collection is spectacular. What’s on display is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Nasreen Askari’s fieldwork traced the roots of embroidery styles and weaving techniques to specific communities and villages in Pakistan.

The original plan was to use about 1,500 square feet (139 square meters). “We ended up not just doing a renovation,” he says. “We also took over their garages, parking space and some storage areas. Now it’s about 3,500 square feet [325 square meters].”

The collection still strains against its physical limits. “The pieces need their own space to be seen from the right distance, in proper light.” Alam chose a neutral palette to ensure that the exhibits stand out.

The museum’s layout flows organically through five galleries, allowing visitors to walk seamlessly from one space to another. Alam feels proud the renovations don’t make it “look alien or like someone has imposed a style. It feels like this was always there.”

Making textile collections accessible

Experts say the timing of this project couldn’t be more urgent. “When you look at the crafts even from just 60, 70 years ago, they were of a different quality,” says Iram Zia Raja, dean of the faculty of design at the National College of Arts in Lahore. “They were created when life was slow, before industrialization; hence, a unique purity of design.”

Raja, herself a collector, has a deep personal connection to textile crafts, especially vintage phulkaris.

To her, these older pieces hold lessons that no design school can teach. “They were created by people who didn’t go to art college, or even to school. Yet their color sense, rhythm, compositions are flawless.”

Bilal also highlights the importance of having such collections accessible. “We don’t get to travel to the provinces. The museum becomes the site where you’re exposed to textile collections from across Pakistan,” she says.

The museum’s mission is ambitious: “to preserve, protect, conserve, document and display Pakistan’s textile heritage,” Hasan explains. “We want to proclaim what Pakistan has to offer to the world.” And that offering is vast.

The museum, still in its early days, is grappling with logistical hurdles. “We’re still figuring out lighting and conservation,” Hasan acknowledges.

Textiles representing different regions of Pakistan are on view.

The redesign and renovations were also driven by budget constraints. “I would have loved for all of these pieces to be behind museum glass,” says Alam, the architect. “There is provision to do that only for some pieces placed within niches.”

Despite these limitations, the impact is immediate. “I see people walking by discovering that there is such a museum,” says Alam. “It’s an eye-opener. More people need to be aware of how rich this land is.”

In addition to five seamlessly connected galleries, the museum includes two gardens, once intended to be closed off to the public. “But then it was decided to let the public move through it,” says Alam. “Having a lung like that in Karachi, as a public space, is really precious.”

Yet even in its nascent state, Nasreen ki Haveli has begun to draw international visitors. “Footfall is the lifeblood of any museum,” says Hasan, “so the gates are open and will welcome everyone.”

Even the name of the museum was chosen with care. “We wanted an Urdu word,” Hasan explains. “A haveli can be an old house or a haven. We wanted people to feel it was a place of refuge, and it is a refuge for these textiles.”

As a solid initiative for cultural preservation, Nasreen ki Haveli offers a model rooted in love, labor and identity. It is, as much as anything else, a promise to the past and a gift to the future.

“The mission,” Hasan says simply, “is to keep the flame alive.”

About the Author

Khaula Jamil

Khaula Jamil is an independent photographer, photojournalist and filmmaker from Pakistan whose work has been published in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Economist, Global Citizen, Rest of the World and more. Passion projects include documentaries highlighting positive movements in her hometown’s marginalized communities.

Sunniya Ahmad Pirzada

Sunniya Ahmad Pirzada is a Peabody Award-winning journalist whose work focuses on the intersection of race, class and gender and how it impacts people and societies around the world.

You may also be interested in...

Al Sadu Textile Tradition Weaves Stories of Culture and Identity

Arts

Across the Arabian Gulf, the traditional weaving craft records social heritage.

Orion Through a 3D-Printed Telescope

Arts

With his homemade telescope, Astrophotographer Zubuyer Kaolin brings the Orion Nebula close to home.

‘Home’: Arab American National Museum Celebrates 20th Anniversary

Arts

Arab American National Museum Director Diana Abouali says the facility—which is marking its 20th anniversary in 2025—in Dearborn, Michigan, has aimed to create a home for Arab Americans by preserving and presenting the history, culture and contributions of Arab immigrants as well as their native-born children and grandchildren.