Fusion Music Ensemble Boom.Diwan Revives Arabian Gulf Pearl-Diving Songs

Fusion-music ensemble Boom.Diwan honors the historical Arabian Gulf way of life with a blend of traditional rhythms and vocals with jazz improvisation.

Standing at the edge of a dhow, Ghazi Al-Mulaifi removed the cloth around his waist and placed his foot into a loop at the end of a rope with a rock tied to it, heavy enough to plunge him into the depths. Then he leapt into the Arabian Gulf waters off Kuwait to collect oysters in a basket, in hopes that some would contain pearls.

For Al-Mulaifi, a Kuwaiti guitarist and ethnomusicologist, the mission of diving was more than a search for the gems. He was trying to experience a life led by his grandfather, who was one of the last pearl-diving shipmasters, to piece together a family history he had never known about.

Al-Mulaifi performs in 2022 in New York with Arturo O’Farrill and the Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra.

Banning Eyre

“My grandfather and I were close,” he recalled. “He was an extremely gregarious and funny guy, so I asked him, ‘Hey, tell me about life at sea.’ He just said, ‘All the men died at sea.'” Al-Mulaifi knew not to ask more. Still, the memory lingered. “That’s where my curiosity about this whole lifeway was born.”

Two decades later, Al-Mulaifi learned that music played a central role in the hunt for pearls. “It made pearl-diving life possible,” he says. The music of pearl divers led him to create one of the most unusual musical ensembles in the Gulf region: Ghazi al-Mulaifi and Boom.Diwan with Arturo O’Farrill.

And now these musicians conjure a moody, at times joyous, swirl of traditional Gulf rhythms and deeply sonorous vocals, with inspired jazz improvisation on piano, saxophone and electric guitar.

Boom.Diwan … provides an accessible entry point through which … audiences can be subtly introduced to Gulf sounds, rhythms and timbres.

The boatswain and crew of the Triumph of Righteousness sing and drum as they sail into Oman’s Mutrah Harbour in 1939.

Courtesy of National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Pearl-diving music

The connection between a profession that involves life-threatening dives into deep waters in search of the perfect pearl and trancelike, rhythmic music—played on clay pots and barrel drums and led by a powerful, high-pitched male voice singing over a deeply droning chorus—may not seem obvious.

“Among the highest-paid members of each [boat] for pearl-diving expeditions is a naham. A naham is a singer, and shipmasters would fight over the good nahams,” Al-Mulaifi explains, “because they would keep the spirits of the sailors up for the expedition.”

The songs of the naham literally choreographed the complex activities of a pearl-diving expedition: when to trim the sails, when to drop anchor, when to send divers into the waters and, crucially, when to bring them back up safely.

Pearls were in high-fashion demand all around the world, and the banks off Bahrain and Kuwait provided the principal source. Prior to the discovery of oil in the 1930s, pearl diving was the backbone of the region’s economy. One could argue the naham and his musicians were about as important to sustaining life in the Gulf as any musician could be.

Bahraini ethnomusicologist, musician and composer Hasan Hujairi also studies pearl-diving music from his base in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Hujairi notes that these days the most authentic pearl-diving music is performed in private ceremonies, in long, narrow rooms that echo the feeling and social hierarchy of a pearling boat.

Pearl Divers and Their Songs

Fijeri (sea music): pearl-diving music genre dating to late 19th century

Sound: hypnotic call-and-response vocals by lead singer and chorus, often with rhythmic clapping, stomping and drums

Use: accompanied actions such as rowing, setting sails and pulling up the anchor

Themes: longing for loved ones, dangers of the sea, praise of God and hope for fortune

Sources: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, UNESCO

On the actual boats, the stakes were high, as divers routinely risked drowning and decompression sickness (the bends) if the naham’s timing was off. Hujairi calls the songs “a matter of life and death,” but he says that the culture of pearl diving had broader implications as well. “We talk a lot about the songs, but the pearl industry doesn’t only affect music. It affects the language. It affects the food.”

The sea didn’t separate people, Hujairi says, but rather it connected them. “When people traveled across it, their languages and cultures came with them. Instruments and music styles originating in Persia, India, Kenya and Zanzibar found new homes on the Gulf coast.”

Lisa Urkevich is a professor of musicology and ethnomusicology specializing in the heritage and music of the Arabian Peninsula. She says, “Pearl diving in the Gulf dates back to the Neolithic Period, maybe 7,000 years or so. … The origins of this music are impossible to pinpoint.” That doesn’t preclude origin stories.

Regardless of its exact origins, the cultural intricacies pearl-diving music have intrigued many, including Bill Bragin, executive artistic director for New York University’s performance center in Abu Dhabi. In 2019 he conceived of a concert project called The Cuban-Khaleeji [Gulf music] Project. For that Bragin thought of Al-Mulaifi, an artist with an expansive sense of Gulf music’s possibilities.

That idea underscores that this is global music, with cultural connections well beyond the Gulf.

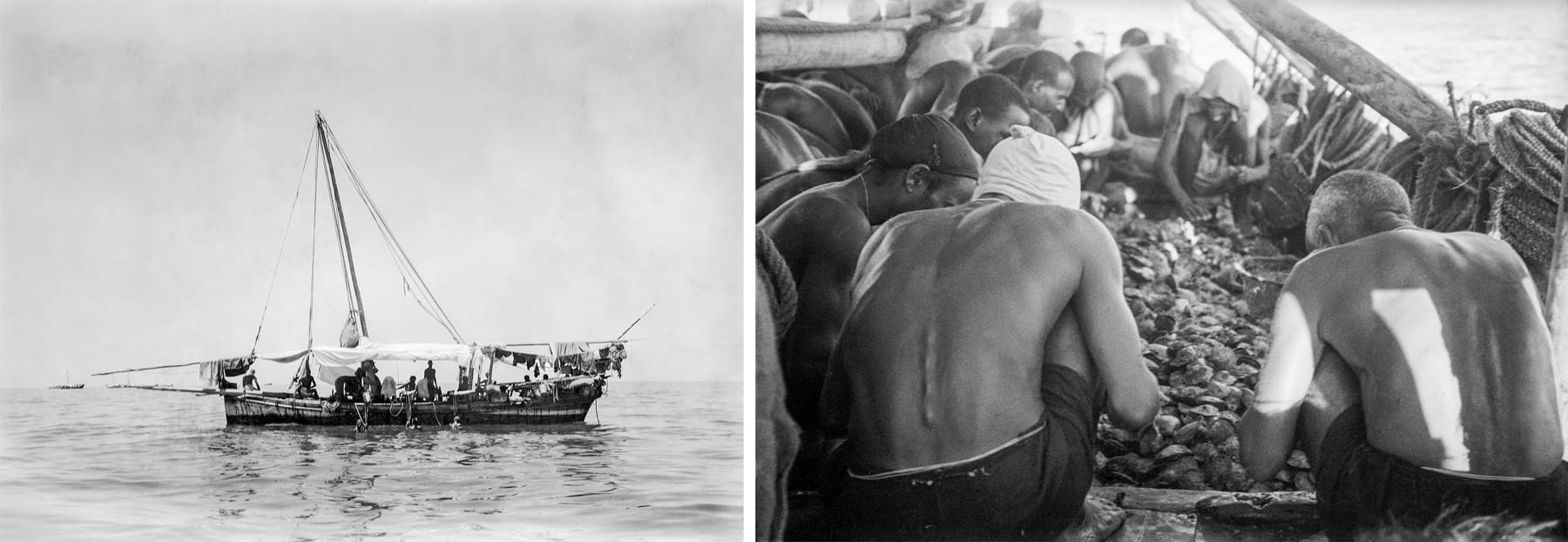

Left: Prior to the discovery of oil in the 1930s, pearl diving was the backbone of the region’s economy. Right: Divers look through the prior day’s catch before heading back into the water.

Courtesy of National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Ghazi Boom.Diwan project

Al-Mulaifi’s ensemble began as a fusion of pearl-diving music and jazz. Bragin’s idea was to invite composer and piano maestro Arturo O’Farrill, leader of New York’s Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra, to collaborate with Al-Mulaifi’s pearl-diving musicians to see what would happen.

O’Farrill’s interest was piqued when he read Ned Sublette’s expansive book Cuba and Its Music, which begins with deep pre-history. He recalls his revelation. “I had never thought about the fact that Spain, Northern Africa and the Middle East were all part of this trade route—slavery and spices and all kinds of stuff. And so there’s a lot of what [Sublette] calls Arabic and Spanish musical practice in northern and western Africa.”

He knew he had to do something about it.

O’Farrill first encountered the pearl-diving musicians in Al-Mulaifi’s living room where a righteous jam session ensued, with the players exchanging their own familiar rhythms. He recalls, “I’ll be damned if these pearl-diving percussion masters did not remind me of guaguanco [a Cuban folkloric rhythm] and of all the beautiful, traditional call-and-response practices found throughout Africa and Latin America.”

Al-Mulaifi was similarly amazed. “Arturo was saying, ‘Oh, that’s a bomba, or a plena [Puerto Rican rhythms],’ and my guys were like, ‘This is a banati.’ And they’re all playing the same thing. So there was this huge moment of recognition, with Africa in the center, connecting everything.”

Diving for Pearls

Boats: wooden, light and maneuverable

Equipment: basic gear (tortoiseshell nose clips, finger guards, tug ropes, weighted stones and baskets)

Crew: 10-30 men

Depths: 12-40 feet (3.6-12 meters) in typically calm Gulf waters

Dives: 50 per day, each lasting about 1 minute

Peak: 1912, the “Year of Superabundance,” before rise of oil and cultured-pearl industries

Sources: Frontiers USA, Kuwait News Agency

Just like that, a collaboration was born. The most important type of pearling dhow in Kuwait is called a boom, and the word diwan comes from the Turkish word for a salon. “So the boom is about going out, and the diwan is about welcoming people in,” says Al-Mulaifi. “Arturo was like, ‘Boom, boom. It sounds cool. That’s it! That’s the name of your band: Boom.Diwan!”

Al-Mulaifi’s grandfather’s reluctance to recall his pearl-diving life may have had to do with more than memories of friends lost at sea. Hujairi notes that during the off-season months, pearl-diving musicians performed a style of ritual music called fijeri. Freed of the constraints of a pearl-diving mission, fijeri musicians would stretch out in lengthy, sometimes all-night, ceremonies, still preserving the hierarchy that governed the boat, with the naham and elders at the top, but exploring a larger repertoire of rhythms and moods.

In colonial times, says Hujairi, “The British were afraid of the pearl divers. They saw these fijeri gatherings as potentially dangerous because you have men from a community gathering at night singing and talking, and this talking could mean they want to rebel or protest.”

To avoid detection, fijeri musicians dug out the floors of their houses so that patrolling policemen would not see their heads through the windows. “This way,” says Hujairi, “it remained a very secret activity for a number of decades in Bahrain.”

In forming Boom.Diwan, Al-Mulaifi had to earn the trust of the pearl-diving musicians, especially percussionist Hamad ben Hussain, whose great-grandfather was responsible for introducing the Indian barrel drum to the tradition in the early 20th century. “Hamad took a while to play with us,” recalls Al-Mulaifi, “because he wasn’t sure what I was doing was respectful enough. All these guys are part of the traditional Kuwaiti music diwaniyas [salons for gatherings].” As it turned out, their devotion to tradition did not rule out cross-cultural collaboration.

Boom.Diwan with Arturo O’Farrill performs in 2022 at NYU Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Waleed Shah

For Al-Mulaifi, this project is personal. “This pearl-diving music is not being respectfully represented on the national stage,” he says. “One of the main things we’re trying to do is to put the music back in the kind of situation that occasioned it, not looking to represent any nation or state, because when this music was played, those realities didn’t apply.”

On stage the complete ensemble presents a spectacle, with the pearling musicians and their drums aligned on one side, O’Farrill and his piano on the other, and Al-Mulaifi with his guitar and the band’s bassist and saxophonist at the center.

It’s a fluid endeavor. Boom.Diwan has also recorded and performed with South African jazz maestro Nduduzo Makhathini. The project is part of a new wave of experimentation in Gulf music.

Urkevich says, “Music like that of Boom.Diwan plays a unique role: It offers a modern expression of regional identity, provides an accessible entry point through which both local and international audiences can be subtly introduced to Gulf sounds, rhythms and timbres.”

Pearl diving may be consigned to the pages of history, but the music that provided its spirit and tempo live on, reinvented for our time.

You may also be interested in...

2026 AramcoWorld Calendar - Football Is Life

Culture

In urban centers and tiny villages, amid plains, deserts, forests, rainforests, coastal areas and any other habitat on our spinning sphere, football found a formidable foothold.

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

Handmade, Ever Relevant: Ithra Show Honors Timeless Craftsmanship

Arts

“In Praise of the Artisan,” an exhibition at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, aims to showcase Islamic arts-and-crafts heritage and inspire the next generation to keep traditions alive.