I Witness History: I, Horn of Africa

Royal trumpet of Pharaoh Tutankhamen, I was born to command armies, priests and whole populations. But my days with him were few. Layed to rest with my mouthpiece toward my 19-year-old pharaoh, I fell silent for 3,262 years. Then one of you tried to play me.

Let me give you some sound advice. We all live in a world of noise. Mine echoed with the grunts of crocodiles, the tramp of cattle, the banter of workmen and the wails of mourners. Yours endures the rumble of traffic, the pounding of jackhammers, the blare of televisions and the thump-thump-thumps escaping alike from nearby headphones and helicopters. In all this chaos and cacophony, your ears struggle to identify the sounds that matter: Is that my car backfiring? Are those crocs near my feet? Is there an aircraft landing on me, or is that just the heavy bass of someone’s playlist? You need help, and that’s where I come in. At least I did, long ago.

Called a sheneb in the language of the pharaohs, I am a royal trumpet. I was invented to cut through useless noise and let it be known that something important should be heeded. In full-throated blare, I announced to his people the god-king’s arrival on state occasions; I summoned worshipers to religious observances; I even commanded armies on the battlefield. Whereas your modern trumpets play, we sheneb worked for our livings. Our mission was never to make idle toes tap, but to bring order to the world around pharaoh. We were the ultimate communication technology of our day—megaphones, microphones and mass media all in one.

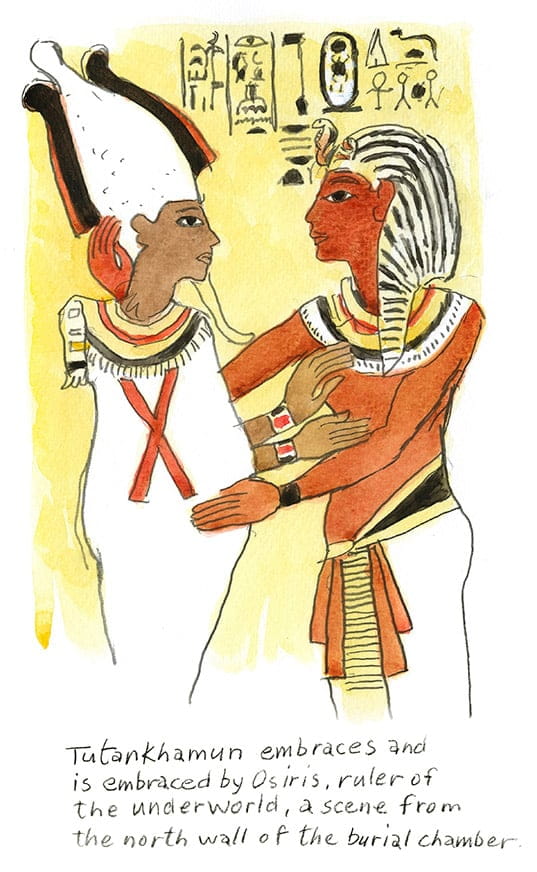

Our usefulness made us the mainstays of war and religion throughout the Middle East. My ancestors spread across North Africa and then into Spain and far beyond. In many places, the sheneb-like nafir still trumpets during Ramadan, and some say your English word “fanfare” actually derives from al-nafir. Many diverse believers expect us to make the final sounds of this world on Judgment Day. This expectation reminds me of the Egyptian legend that it was Osiris, lord and judge of the underworld, who invented the very first sheneb.

Sadly, only two of my family members survive from the long age of the pharaohs. Both of us were buried together in the legendary tomb of Tutankhamun. For years, my brother and I had given voice to the boy-king’s every command. Our different pitches allowed the right people to respond appropriately to our distinct calls, much as you program your cell phones with personal ringtones. Do not doubt, however, that I commanded the greater respect, as established by my fancier uniform. I, glistening in silver and gold, am the general; my little brother is my adjutant. I stand 58.2 centimeters tall, whereas he is shorter and made of copper alloy. My shape resembles, quite deliberately, a tall lotus in bloom. In fact, the unmistakable design of Nymphae caerulea Savigny has been pressed indelibly into my bell. There, too, a pair of my pharaoh’s many names may be read, recorded in two sets of cartouches that spell out Nebkheperuretutankhamun, followed by one of his royal titles. These hieroglyphs have been oriented so as always to be read from the vantage point of the trumpeter, meaning that no matter who might sound me on his behalf, I am the voice of Tut himself.

Producing this sound was hard on the trumpeter. The trumpeter gripped me tightly by the throat, usually with both hands, and with a firm kiss issued the requisite number of blasts to convey pharaoh’s bidding. This took skill and stamina; in fact, the Greeks later made trumpeting an Olympic sport.

Because I needed to be with Tut wherever he traveled, in peace and in war, I required a wooden insert to protect me from dents and other damage. This body double, called a core or stopper, preserved my shape during the busy nine years of my pharaoh’s reign, and for the 33 centuries since. Painted red, blue and green to appear also as a lotus, this core is removed only when I am called upon to speak for pharaoh. In some Egyptian artwork, the trumpeter can be seen cradling the stopper under his arm while blowing the horn itself. Given my long tubular construction, I am ironically a fragile thing of power—as one of your bumbling modern musicians can personally attest. You will soon learn that after what he did to me, I am lucky to be alive.

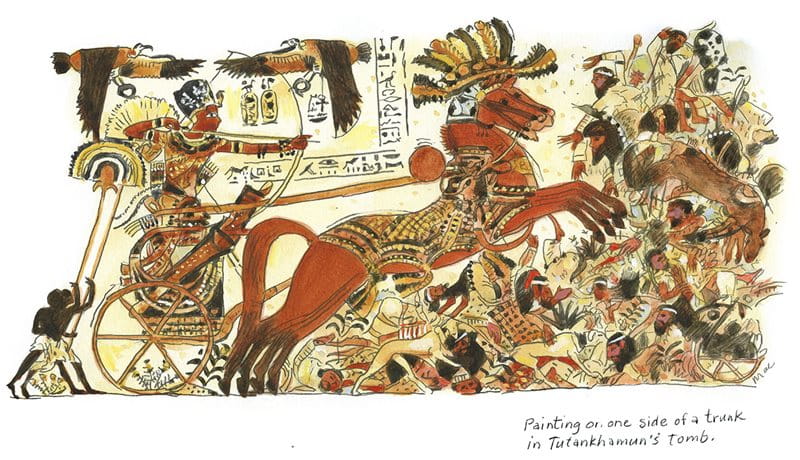

Then, in a year now called 1323 BCE, I fell silent alongside my pharaoh. No one knows to this day exactly what illness or injury transformed Tut from living Horus to resurrected Osiris. The news that winter came as a terrible shock, since he had been idolized as the very image of youthful vitality in spite of his limp. Tutankhamun stood 1.7 meters tall, less than three times my own height, but he towered in the minds of his people. He smiled with unusually healthy teeth (a sheneb notices), and he enjoyed an adventurous if abbreviated life. Tut had a great fondness for chariots, and it is still rumored that a violent crash may have injured his left thigh and contributed to his death. No royal tomb was ready to receive him so young, thus attendants piled into a borrowed grave the treasures of this fallen teenager: six of his favorite chariots, eight fine shields, four swords and daggers, 50 bows and other weaponry. They also stacked boxes, beds and model boats. Clothing and cosmetics vied for space next to jewelry and jugs of wine. Even the two tiny mummies of Tut’s stillborn children were stowed inside the tomb. I, along with my brother, joined pharaoh in these cramped quarters—he in the antechamber, but I more prestigiously in the burial chamber, my mouthpiece oriented toward Tut.

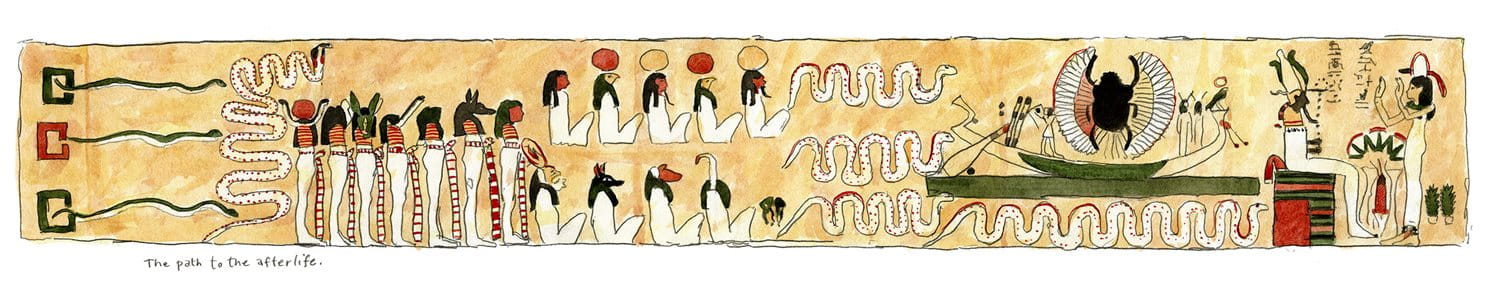

Do not imagine, in your modern way, that in that dark abyss I despaired. Along the Nile, the buried stay busy. Tut the eternal teenager lived on; I could hear his bird-like ba (soul/ personality) come and go as it pleased, its flight unhindered by the eight meters of rock above us. Sometimes, I sensed tremors as workmen nearby chiseled out more tombs, followed by the faint trudge of feet as funeral followed funeral in the Valley of the Kings. I now know that a tomb begun by Ramses v crossed directly over Tut’s and continued 116 meters into the rock, angling over the tomb of Horemheb (whom I knew as one of Tut’s generals) and eventually crashing into the tunnels of yet another grave! It was like a gigantic ant farm.

Much was taken, but so were some of the robbers. I suppose these captives were tortured and then impaled according to custom. A great deal is known about the tomb robbers of ancient Thebes thanks to the survival of their case files. Papyrus records immortalize their misdeeds. I am ashamed to say that a sheneb player named Perpethewemōpe was among the worst of these thieves. He dared supplement his wages by plunder and even falsely accused a fellow trumpeter named Amenkhau, with whom he had a grudge.

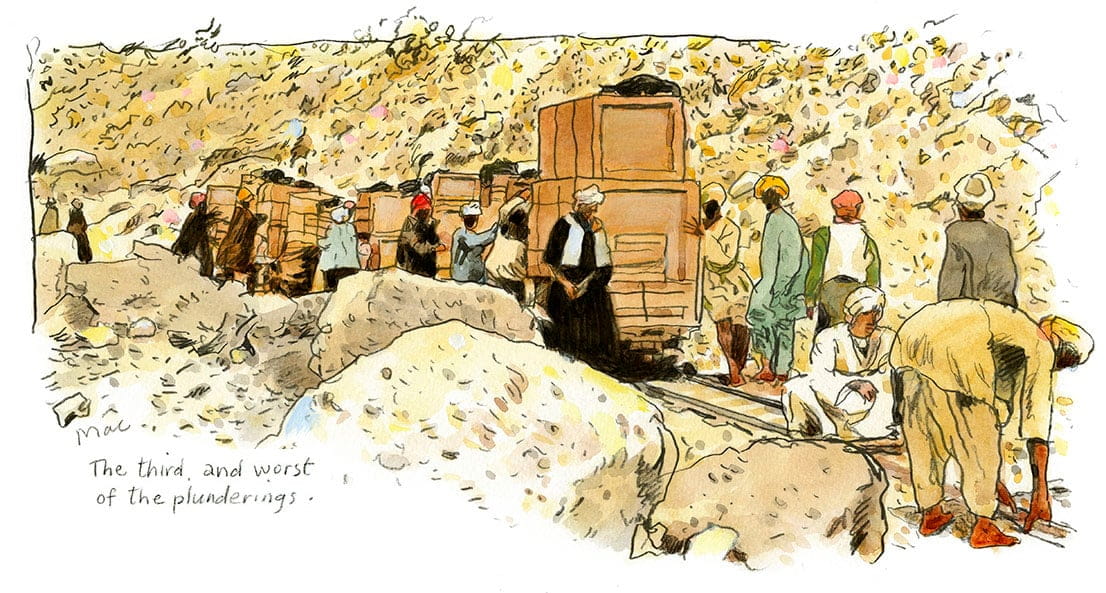

In Tutankhamun’s tomb the mess was heartbreaking. The royal scribe Djehutymose inventoried the disheveled tomb and hastily repacked its contents, leaving me beside the king’s burial shrine, wrapped in reeds beneath a beautiful alabaster lamp. There I lay contented until the third— and worst—of the plunderings.

Muted, I watched the robbers creep away. They painstakingly concealed the breach they had made in the door as if to deceive the necropolis police. Many months would pass before two of them came back; the third had apparently died in the meantime from the infected bite of an insect, and his demise was immediately blamed on Tut, just as I would eventually be accused of killing Howard Carter—along with 60 million other of his fellow humans.

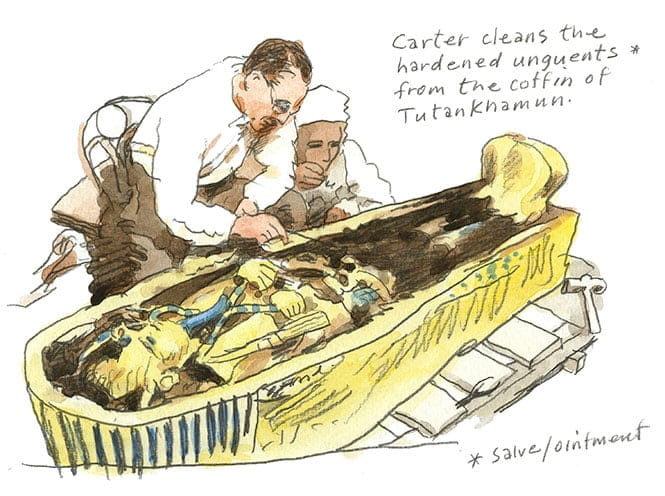

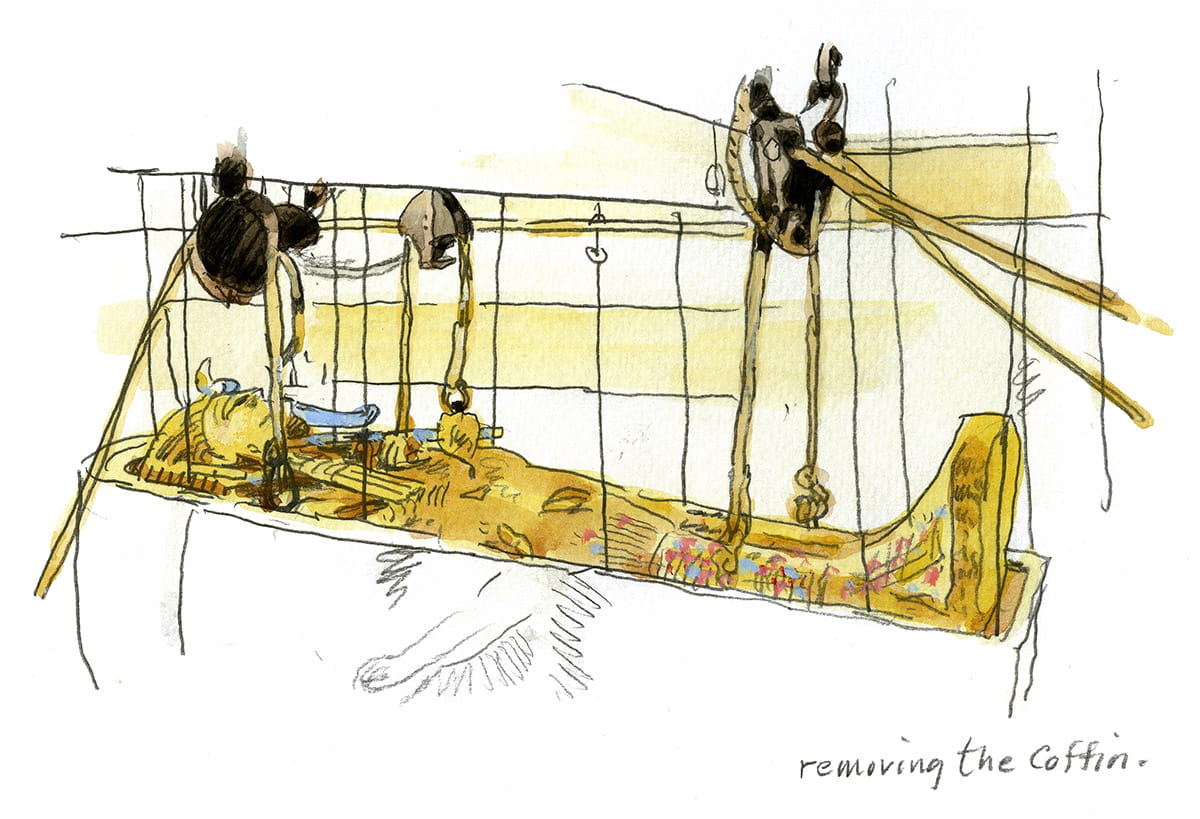

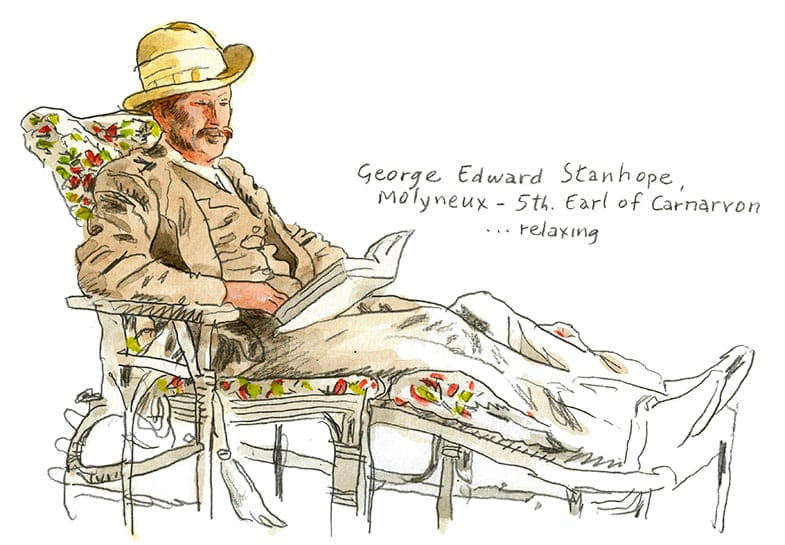

On February 16, 1923, Carter and his crew “officially” opened the burial chamber in the presence of a small audience seated comfortably in the antechamber. Few of these spectators knew anything about the secret intrusion made some weeks earlier, so the robbers feigned surprise at everything they found, including me. I was scooped from the floor and studied, as recorded in Carter’s notes. I was given an unpleasant cleansing in ammonia and water; my wooden core was treated with something called celluloid. In a letter he later wrote, Carter let slip another of his little secrets involving me: “Though I am no expert with such musical instruments, I managed to get a good blast out of it which broke the silence of the Valley.” Yet the alarm I finally sounded (in Tut’s name, you recall) brought no one—no necropolis police, no royal troops, no one at all. Where had they all gone? Incensed at such insubordination, I soon was posted to the Egyptian Museum at Cairo, 600 kilometers away from the crypt and king to whom I still belonged.

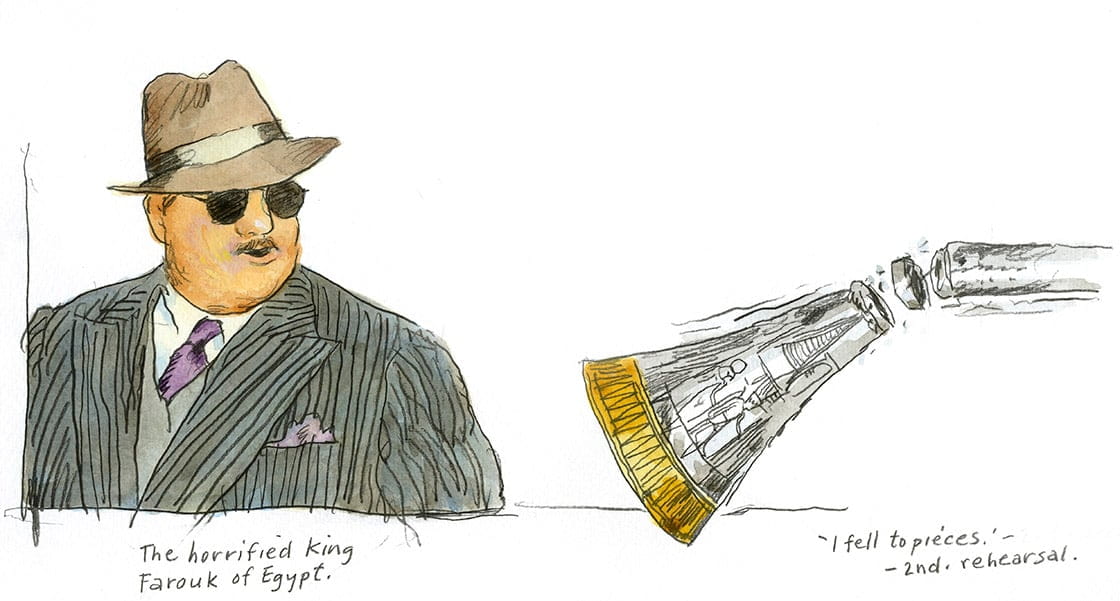

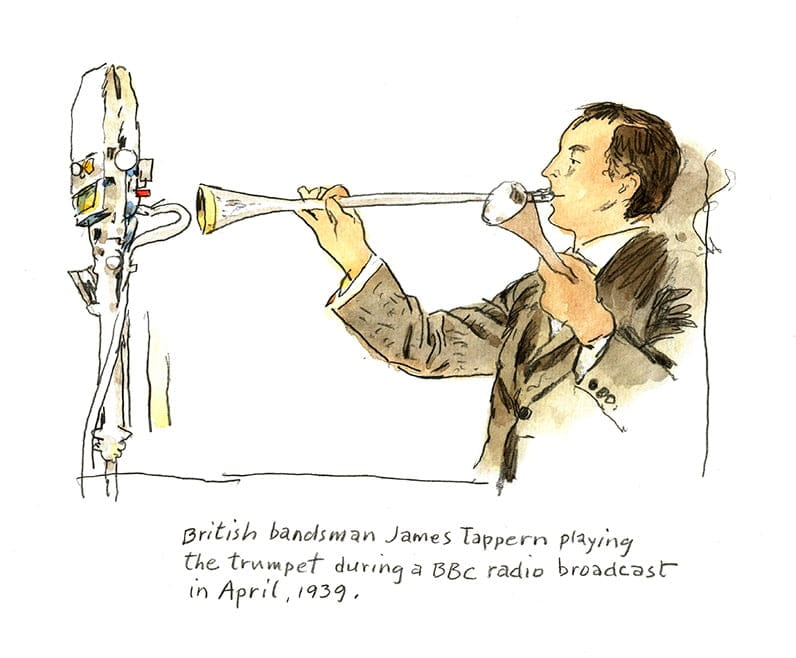

Six years later, I spoke up again, but in a strange new way. A radio pioneer named Rex Keating arranged for me to broadcast a message from the Cairo Museum that would be heard all around the world. Keating, of course, knew that I could only issue a single note, and this he deemed unworthy of the event. So, he allowed a military trumpeter stationed in Egypt to stuff a modern mouthpiece down my throat in order to play some sort of tune. During the second rehearsal, the strain was too much, and I cracked. Then and there, in the presence of a latter-day pharaoh named Farouk, I fell to pieces. The horrified king, trumpeter and museum staffers dropped to their knees and scrambled to recover my broken remains. All witnesses to this disaster were sworn to secrecy, lest the world be outraged at my mistreatment. While experts labored feverishly to restore me to life, much as Isis had done for Osiris, Keating searched for a more reliable musician. He chose a British bandsman named James Tappern, who treated me with greater respect according to my superior rank.

I have only performed twice more since that day. In 1941 I sounded a few notes as part of an acoustic experiment conducted at the Cairo Museum. Later, in January 1975, I blared another brief solo. The trumpeter, famed musician Philip Jones, said of me: “Its sound was not exactly melodious ... but it was probably the most thrilling experience I shall have as a trumpet player.”

Now, given my advancing age and recent misadventures, I may never sound again, although, in the fashion of your civilization, I have been on tour for some time now. I have been traveling first class again, learning along the way that beyond my native Nile, many lands exist. Your towns are of course much harder to pronounce than my Tjeb-nut-jer, Hut-Tahery-Ibt, and Taya-Dja-yet. Go ahead, try to say them: Fort Lauderdale, Chicago, Dallas, London, Melbourne. I find the fan-frenzied exhibitions in these exotic places fascinating from my side of the glass. Children no older than Tut when he ruled an empire crowd around my case, their mouths blowing into their little fists as if to make me speak. Kids naturally appreciate anything meant to make a noise. They jostle and joke about mummies and curses, while their elders hum a trumpet-laden parody linked to a certain Steve Martin and his band, the “Toot Uncommons.” Apparently, Tut was once celebrated in a festival called Saturday Night Live. I watch these antics indulgently, mindful that you honor Nebkheperure Tutankhamun in your outlandish way even as I, still dressed for his funeral, cherish for eternity his memory in my traditional fashion.

About the Author

Frank L. Holt

Frank L. Holt (fholt@uh.edu) is professor of ancient history at the University of Houston as well as founder and director of the Houston Mummy Research Program, to whose members and contributors he expresses his thanks.

Norman MacDonald

When artist Norman MacDonald compared his own brushes, inks and watercolors in his Amsterdam studio to records of those in Egypt as long as 3,500 years ago, he says he “realized again how little the tools of a painter’s craft have changed.”

You may also be interested in...

How California's Date Fruits Became America's Arabian Superfood

Food

History

In recent years in the United States, dates have been trending as a nutrient-dense, easily transportable source of energy. Nearly 90 percent of US-grown dates are from California’s Coachella Valley. Yet the date palm trees from which they are harvested each year aren’t native; they were imported from the Arab world in the 1800s. Over the years, they have become a part of Coachella’s agricultural industry—and sprouted Arab-linked pop culture.

The Bridge of Meanings

History

Arts

There is no truer symbol of Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina, than its Old Bridge. The magnificent icon of Balkan Islamic architecture was destroyed during the 1992–’95 war—but not for long. Like the multicultural workforce that produced the original hundreds of years earlier, a broad team of architects, engineers and others came together immediately to plan its reconstruction. This summer marked the 20th anniversary of the bridge’s reopening.

Pearls, Power and Prestige: The Symbolism Behind Byzantine Jewelry

Arts

History

A 1,500-year-old gem-encrusted Byzantine bracelet reveals more than just its own history; it symbolizes an empire’s narrative.