Iraq's First Archeologist

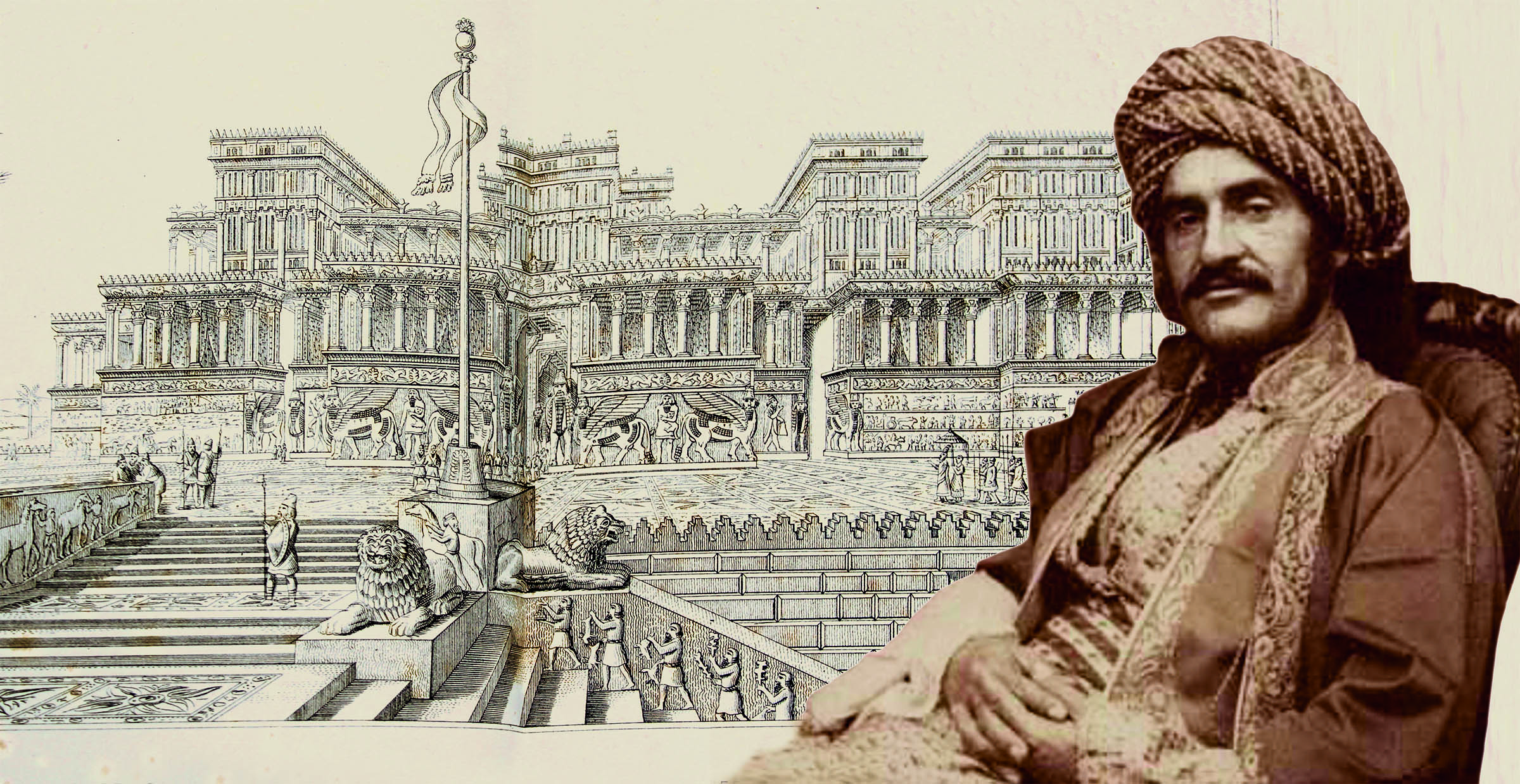

Hormuzd Rassam was 19 years old to help with excavations. Soon he began to uncover long-forgotten palaces–temples at Nimrud and later at Nineveh, splendors of first-millennium-BCE Assyrian kings.

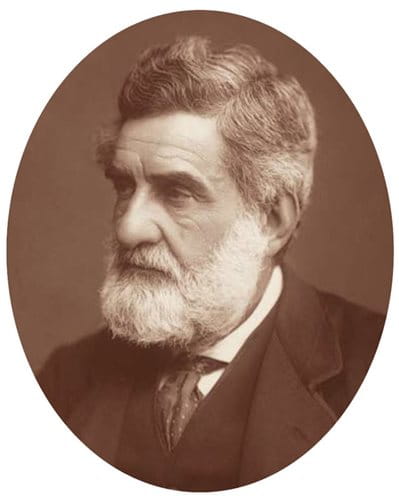

When Hormuzd Rassam went to work in January of 1846 as an assistant to Austen Henry Layard, Rassam was 19 years old and eager to help the man who had come from England to dig out a buried palace near Rassam’s home town of Mosul.

Layard paid a second visit to Mosul in 1842 as an assistant to the British consul general in Constantinople. This time he was accompanied to the Koyunjik mound by the newly appointed French consul to Mosul, Paul Emile Botta, who not only shared Layard’s interest in history, but also had, with the backing of his government, begun excavation there. Though Botta had yet to find much, his enthusiasm inspired Layard.

Hormuzd Rassam came with much to recommend himself. Fluent in Arabic, English and Chaldean, he also added “inexhaustible good humour, combined with necessary firmness, to his complete knowledge of the Arab character,” wrote Layard. “Mr. Hormuzd Rassam lived with me,” he continued, “and to him I confided the payment of the wages and the accounts. He soon obtained an extraordinary influence over the Arabs, and his fame spread throughout the desert.”

Within weeks at Nimrud, Rassam took on increasingly more of the field duties, which afforded Layard, an accomplished draftsman, the time to record the extraordinary finds that were, it seemed, turning up every day. A 1911 obituary written for The Geographical Journal described how Rassam “developed rapidly,” having possessed “that instinctive skill in locating ancient remains.” He quickly climbed to the rank of foreman, second in command only to Layard.

Most of the finds at Nimrud, Layard observed, differed in style and even “surpassed in design and execution” much of what had been revealed recently a few kilometers north at Khorsabad, at the palace of Sargon II, at the time the only other excavated Assyrian palace. At Nimrud, Layard was able to capture much of the detail depicted in the many wall reliefs that were like windows into the Assyrian court: the king performing religious functions, hunting lions, defeating enemies. Layard also noted floor plans of the palace rooms and courtyards as workers were uncovering them.

Layard and Rassam continued working at Nimrud until May of 1847 when, curious as to what else might be found in the area, they moved to survey the two mounds at nearby Nineveh. The smaller, called Nabi Yunus, was accepted locally as the site where the body of the prophet Jonah rested, and that made it off limits to excavations. There were no local objections, however, to excavating the larger mound, Koyunjik. Layard and Rassam began soundings and, based on their trenches, Koyunjik appeared to be even more promising than Nimrud.

On June 14, 1847, Layard wrote the secretary of the British Museum:

The discovery of this building and the extent to which the excavations have been carried out, I conclude, establish our claim to the future examination of the mound should the Trustees be desirous to continue the researches in this country.

In his introduction to the 1970 edition of Layard’s book, Nineveh and Its Remains, British Assyriologist H. W. F. Saggs noted, “it was owing to this fortnight’s work that the British Museum could afterwards claim the rights by which it obtained the famous collection of more than 20,000 cuneiform tablets and fragments from Koyunjik upon which Assyriology is based.”

But it was growing late in the season for archeology. Ten days later Layard left Mosul for England, and he took Rassam with him. “The best time of the year for explorations in Mesopotamia is from September to November inclusive, and from the beginning of March to the end of May,” wrote Rassam, “because, during December, January and February the days are short, and the weather generally wet; and from June to the end of August the heat of the sun is so powerful.”

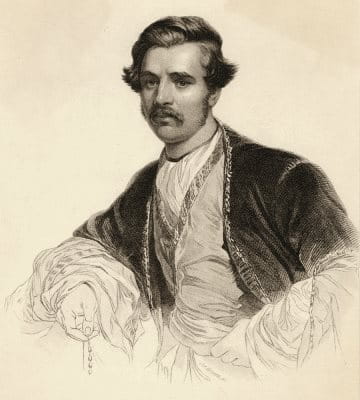

moses coit tyler / bridgeman images; stanford medical history center

Rassam did well at his studies. He did even better at making friends. He learned to ice skate—and to even think it funny when he fell through the ice. He gave his new friends gifts of his own calligraphy, and he waxed proud when one of his examples was exhibited in the university’s Bodleian Library. He became a favorite of the local bishop, who invited Rassam to dinner so often, Rassam wrote Layard, that it became rumored he might marry the bishop’s daughter.

He did not, and in 1849, at the request of the British Museum, Rassam rejoined Layard in Constantinople to return to the Koyunjik mound in Nineveh.

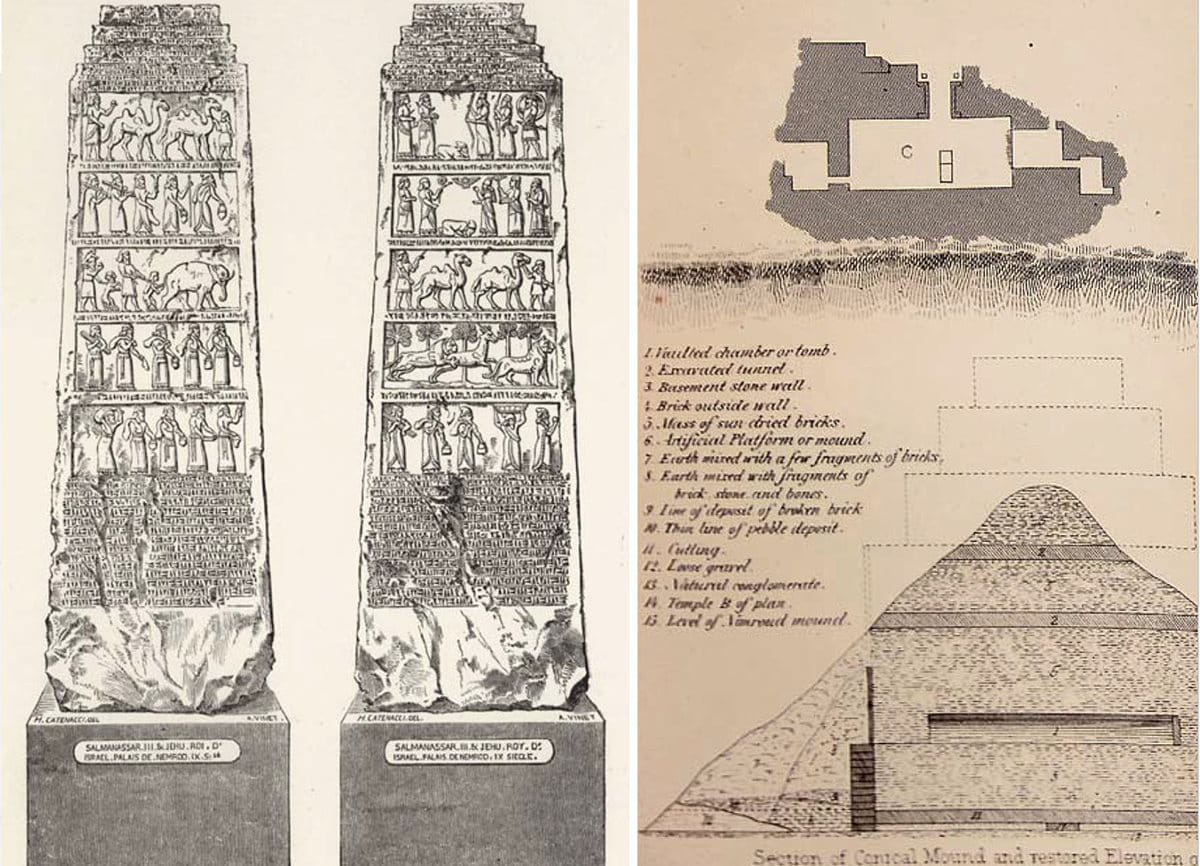

Digging in the mound’s southwest corner, Layard and Rassam soon came upon the vast “palace without rival.” It had been built by the late seventh-century-BCE King Sennacherib, and within it was one of the most spectacularly detailed reliefs of its epoch: a room devoted to a complex relief telling of Sennacherib’s destruction of Lachish, an outpost of Jerusalem at the time of Jehu, the same king who was represented on the black obelisk. Twelve meters long and more than five high, the relief showed Assyrian battering rams and chariots attacking and breaching the city walls as well as the punishments meted out to the rebel leaders afterward.

Although the discoveries were extraordinary, the work conditions were abysmal. By the summer of 1851, the heat and infestations of mosquitoes had taken their toll on Layard who, ill with malaria, left the region, never to return to Nineveh.

With Layard’s departure, the British Museum in 1852 entrusted Rassam, then in England, to carry on the excavation. As Rassam was still only 25 years old, the trustees of the museum asked him to “take charge of the excavations under the general control of Colonel Rawlinson,” an English cavalry officer turned linguist, who then served as British resident in Baghdad, some 320 kilometers to the south of Mosul.

Rawlinson was celebrated for his work copying the trilingual cuneiform inscriptions carved in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE by the Achaemenid King Darius high on a towering rock at Behistun, 550 kilometers southeast of Mosul. Teetering on long ladders, Rawlinson had copied the Old Persian and Elamite inscriptions on several visits beginning in 1836 and, with the help of a telescope and two Kurdish boys, completed copying the Babylonian inscription in 1847. By comparing the three languages, Rawlinson and other scholars came to a crucial determination: Cuneiform was not a language in itself but rather a writing system that, over some 3,000 years, was used for many languages. This meant more work for archeologists: To decipher the languages, linguists needed more tablets.

His ambition was thwarted, however, by Rawlinson and the French consul at Mosul, Victor Place, who agreed to divide the area of Mesopotamian exploration between them as the lure of ever-greater discoveries began to pit the French against the English in a race to claim each potential site. The agreement allotted the north part of Koyunjik to Place.

Rassam was devastated. In his mind, not only was Koyunjik an original British claim, but he also knew that part of the mound was private property upon which the British had long been paying rent. “Moreover,” he wrote, “it was understood, and indeed it is an acknowledged etiquette, that no agent of any museum was to intrude in the sites chosen by the other.” The situation that followed might have been different had Place begun excavating there, but he showed little interest: The French archeologist was making good progress nearly 20 kilometers southeast at Khorsabad and, with limited funding, was not in a position to overextend himself.

Convincing himself that Rawlinson had had no right to assign the northern part of Koyunjik to the French, who in any case seemed uninterested, Rassam resolved to conduct “an experimental examination of the spot at night.” On

December 20, 1853, Rassam gathered his men.

The first three nights brought disappointment. On the fourth, they came upon an ascending passage, which experience had taught Rassam would likely lead to a main building. His instinct did not let him down, and he watched as “a large part of the bank which was attached to the sculpture fell, and exposed a beautiful bas-relief in a perfect state of preservation.” The sculpture represented a king, later determined to be Ashurbanipal, “standing in a chariot, about to start on a hunting expedition.”

Days later, they came upon the main part of one of the libraries of Ashurbanipal, whom scholar Jeanette C. Fincke of the University of Heidelberg credits as having been blessed with “great intelligence,” and “talents to learn the scribal art.” His instructions as king of Assyria, maintains Fincke, to “collect all the tablets as much as there are in their houses” eventually led to chambers filled with compilations of thousands of inscribed terracotta tablets with hieroglyphic and Phoenician characters dating as far back as the Sumerian period (5000–1750 BCE).

Among Rassam’s other notable finds were 16 bronze bands embossed and engraved with figurative scenes and called the Gates of Balawat, after the village, some 15 kilometers northeast of Nimrud, near which they were found. The bands adorned a pair of wooden doors to a palace of Shalmaneser iii. This particular band shows the Assyrian conquest of Khazazu, a city in northwestern Syria known today as Azaz.

Place lost everything excavated in his two years at Khorsabad, including all his notes. The British lost one shipment of lion-hunt reliefs, but most of the wall slabs, and nearly all of the tablets, would make it to England by May of 1856. None of the lost treasures were ever recovered.

By this time, however, Rassam had begun a new chapter. Shortly before leaving Oxford, he wrote to Layard, now a member of the British Parliament. Rassam asked his mentor if he might find him, once the dig was over, a diplomatic post. Layard recommended Rassam to the port of Aden at the southwest tip of the Arabian Peninsula, strategic gateway between the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. In making his recommendation, Layard remembered well Rassam’s innovations in employing gangs of seven men carrying on simultaneous, different excavating tasks. Indeed Rassam rose quickly in Aden to first assistant political resident, a position comparable to a lieutenant governor under the directors of the East India Company.

His work was varied and interesting. He was proud that no one ever asked to reverse one of his decisions while serving as a magistrate, and his genuine interest in helping people won wide praise. In diplomacy he was commended for settling a border dispute with neighboring Muscat (now capital of Oman).

So it was that in the summer of 1864, it seemed only natural that the British government would select him for a sensitive mission: Negotiate freedom for several British missionaries who were being held captive in Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). Warned that it could be both complex and dangerous, Rassam nonetheless set sail in July for the port town of Massowah.

The mission fared badly. It took some three years to resolve—and then only by a British army. Although Rassam was commended for bravery, the British press suggested he had been the wrong man for the job. In 1869, at age 43, he left the foreign service, married Anne Eliza Price, an Englishwoman of Irish descent, and settled in Twickenham, Middlesex, England. There he set out to write his own account of Abyssinia, which he published in 1869.

In four expeditions between 1878 and 1882, Rassam unearthed literally tens of thousands of tablets from sites as far away as Syria and the region of Lake Van in eastern Turkey, as well as from Nineveh, Nimrud and Babylonian cities to the south, including an important cache from the temple of Marduk in Babylon itself. During those years he also located and excavated the Babylonian city of Sippar, famous as “the oldest city known amongst the ancients.” At that site alone, Rassam and his team gathered between 60,000 and 70,000 tablets.

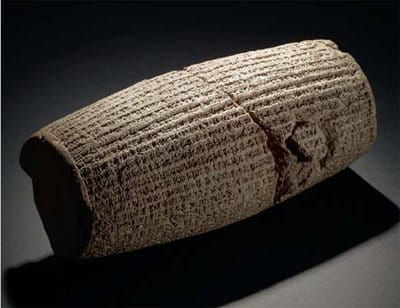

Perhaps his most famous find was a sixth-century-BCE terra-cotta cylinder written by Cyrus the Great and excavated in Jimjima. On it is recorded the capture and enslavement of Babylon by Cyrus’s predecessors.

Another spectacular find was two sets of inscribed bronze bands that once adorned the gate of Balawat, near Nineveh, which is still considered among the most informative illustrations of ancient military campaigns in existence.

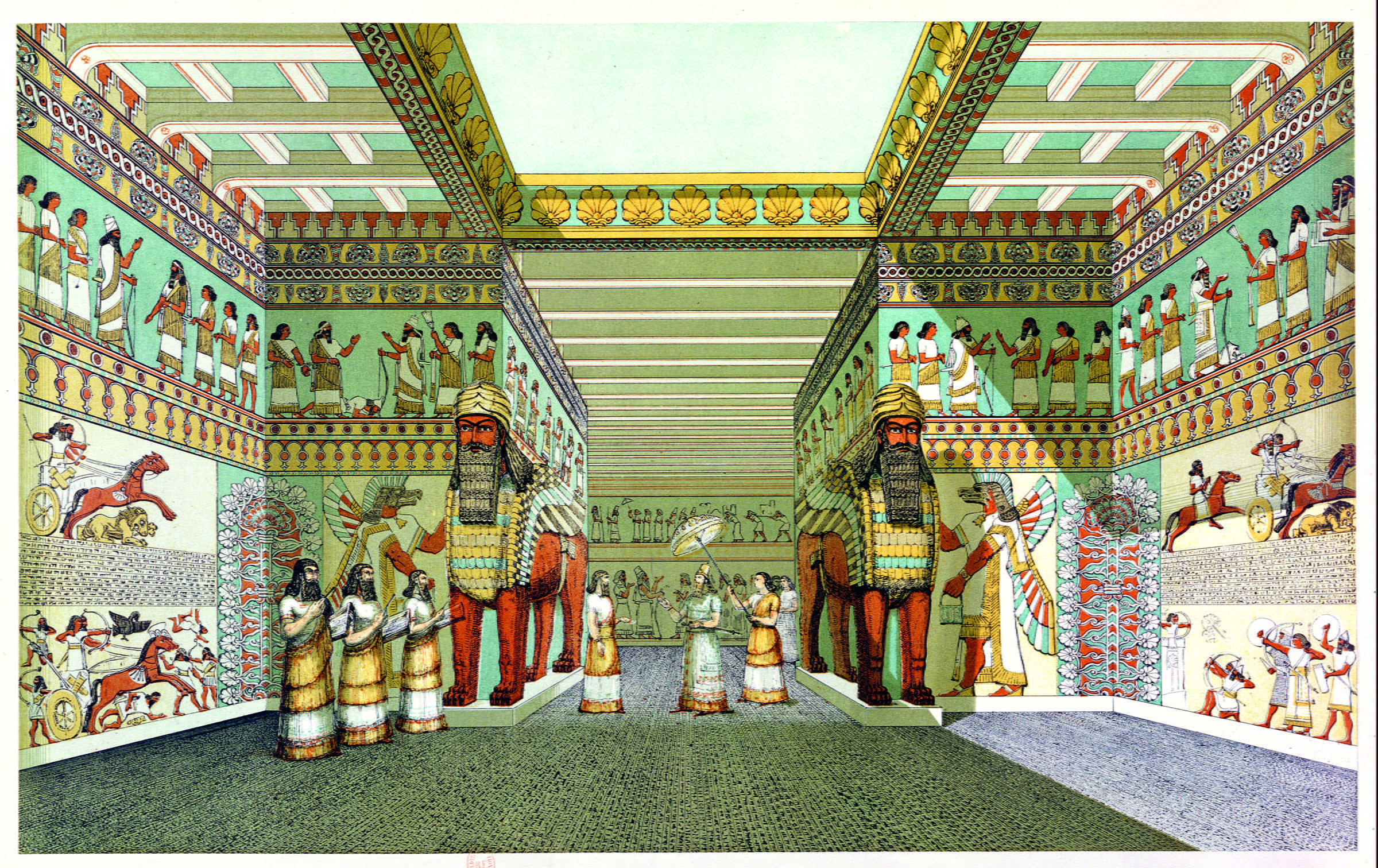

This artist’s depiction of the grand entrance to a four-chambered temple built by Ashurnasirpal II at the northwest part of Nimrud was excavated under Layard and Rassam in 1846. It shows the human-headed lions that today stand on display in London (next); the artist also showed the palace in the vivid colors that may have resembled its original condition.

Now flanking the entrance to galleries in the British Museum much as they flanked a portal of a temple built by Ashurnasirpal II, the human-headed lion figures arrived in London in 1851 together with hundreds of other artifacts.

Moreover, despite Rassam’s pleas, the museum also failed to send out an artist, nor were there funds to buy a camera. With only his trusted workmen to help, Rassam took as much time as he could spare to make his own rough sketches.

There were other difficulties as well. Rassam found the mud brick walls at Babylon almost impossible to differentiate from the dried mud that covered them, commenting that his workmen “are obliged to dig at haphazard as every trace of the old walls is lost.”

Even the tablets themselves were a problem. Other than those at Nineveh, which had been both partially destroyed and partially preserved by fire in 612 BCE, most of the tablets Rassam found were unbaked and, consequently, they suffered almost immediate disintegration when handled. He begged for a linguist to decipher the cuneiform before the tablets crumbled into dust, but in the end, he resorted to baking the tablets in hot ashes before shipping them to London.

Rassam’s biggest hurdle was the scope of his assignment. To uncover as many tablets as possible, Rassam found it necessary to open more than 30 dig sites, a scheme that entailed the appointment of local supervisors so he could move on to other sites. Pilfering antiquities had been a way of life long before Rassam arrived, but with the publication of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the search for tablets exploded, and the incentives to looters had never been higher. As former British Museum curator Julian Reade noted, Rassam had sought the support of guardians of local shrines “by employing them as guards and contributing to the maintenance of their buildings. And he was careful to identify the promising places from which tablets had been coming.” At site after site, Rassam did all he could to prevent theft. But one British Museum curator, Wallis Budge, remained skeptical.

In his later years, Rassam won a libel defense against charges of collusion with artifact thieves, an ordeal that left him at times dispirited, but he continued to publish monographs, including Asshur and the Land of Nimrod.

Layard, who had had his own problems with Budge, was outraged. He rushed to his friend’s public defense, declaring Rassam “one of the honestest [sic] and most straightforward fellows I ever knew, and one whose services have never been acknowledged.” Deeply hurt, Rassam sued Budge in 1893 for libel and won. But the resulting publicity left Rassam’s reputation in tatters. Rather than continue the debate, he retired to Brighton, where he wrote a number of scholarly articles as well as his book, Asshur and the Land of Nimrod, which he dedicated to his old friend, Austen Henry Layard. He died in Brighton in 1910, 16 years after Layard. He was 84, beloved by family and friends.

His considerable contributions to Mesopotamian archeology are well appreciated by those who continue to work in the field, and his name appears prominently in most recent books devoted to the subject.

Perhaps the greatest testimonies to Rassam’s work, however, are the artifacts themselves, the treasures he discovered while working both with Layard and on his own, that today stand among the highlights of the British Museum. Prominently displayed on the main floor, in galleries that transport visitors back millennia, are the famous lion reliefs, panel after grand panel, arranged just as they were found at Koyunjik. The bronze bands of Balawat are now fixed to a replica of the enormous, original gate. A colossal bull and lion from Nimrud still stand as flanking guards at the entrance to the Assyrian galleries, and the Obelisk in Black Marble and the Cyrus Cylinder claim their places among the most visited exhibits in the museum.

Within a decade, Layard and Rassam uncovered three of the four most magnificent Assyrian palaces ever found. Their findings, together with those of Botta, opened the study of Assyriology. Rassam stands alone as the first archeologist both of and from Mesopotamia.

You may also be interested in...

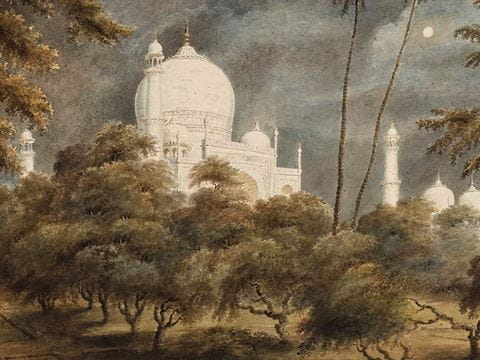

How Historical Paintings of Taj Mahal Changed Perceptions of India

Arts

History

The depiction of the Taj Mahal in the works of Indian and British artists in the 1800s helped bolster enthusiasm for the country & rsquo;s rich culture, architecture and society. One such painting, & ldquo; The Taj Mahal by moonlight,& rdquo; stirred a bidding frenzy at a recent auction, and some experts argue that such paintings have helped change perceptions of India in the West.

AramcoWorld: 75 Years of Cultural Connections

Arts

History

Since its origins in 1949 as a company newsletter for Aramco, AramcoWorld has evolved to focus on global cultural bridge-building across the Arab and Muslim world and beyond.

AramcoWorld Explores Universal Food and Cross-Cultural Identity

Food

History