The Legacy of Arabic in America

The eighth most-studied language in US schools and universities today is Arabic. That would please Edward E. Salisbury of Yale, who in 1841 became the country’s first full professor of Semitic languages—nearly 200 years after North America’s first Arabic class was offered at Harvard.

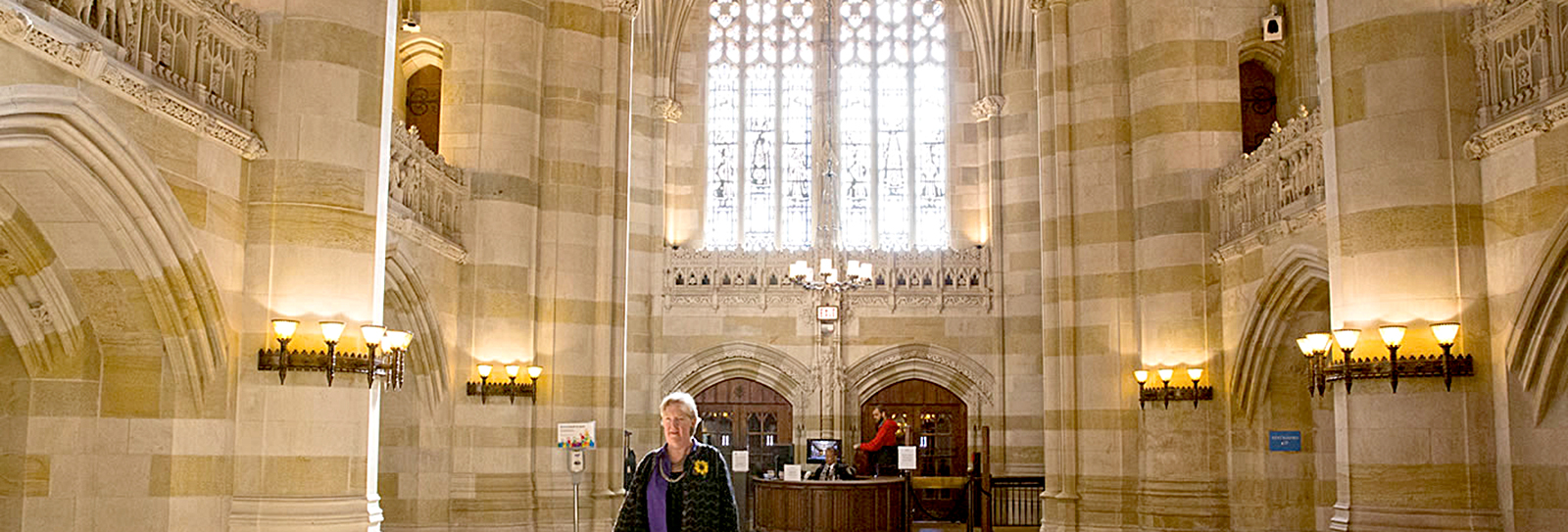

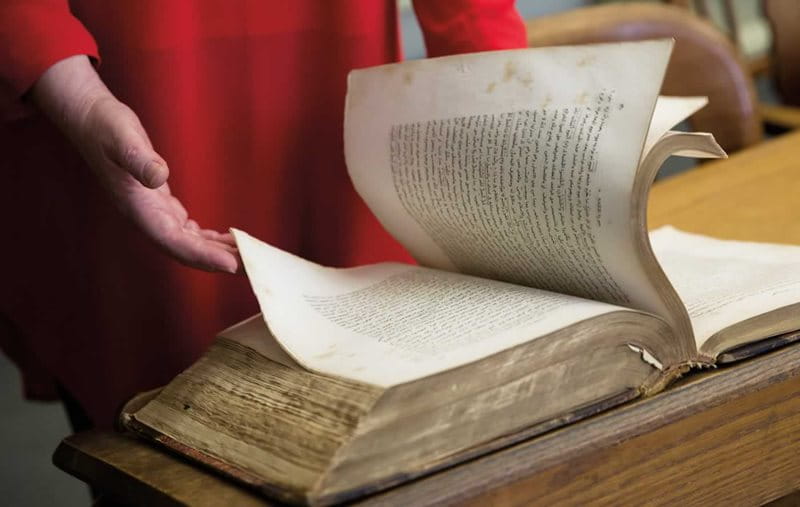

In 2013 the University of Leiden’s announcement of its yearlong celebration of 400 years of Arabic studies in the Netherlands caught Roberta Dougherty’s attention. As the librarian for Middle East Studies at Yale University, she recalls wondering, “If they had 400 years, how long has it been here?”

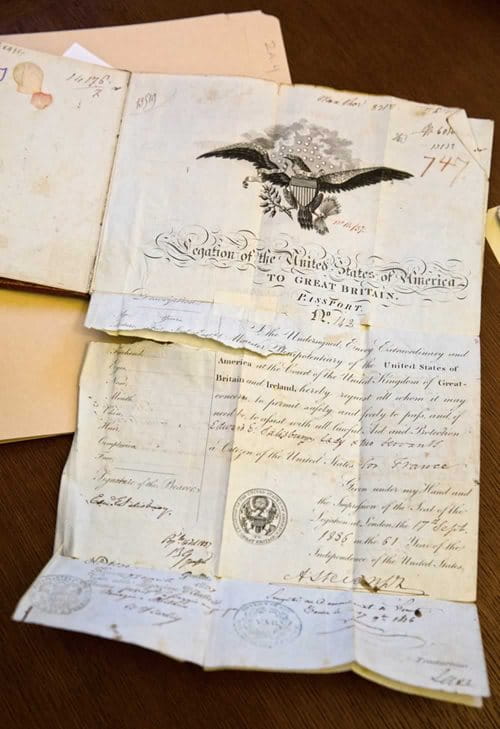

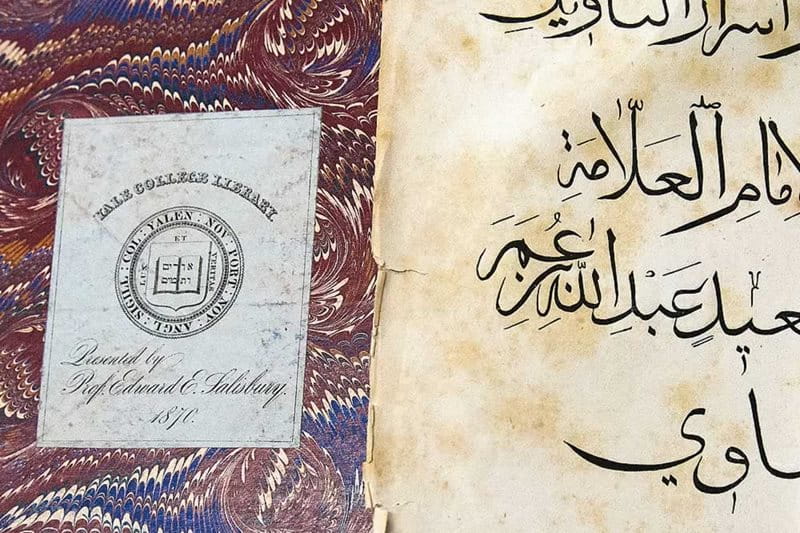

She knew that in 1841, Yale had appointed the pioneering scholar Edward E. Salisbury as Professor of Arabic and Sanskrit Languages and Literature, the first such full-time appointment in the us. Inspired by the Leiden celebration, Dougherty dug into the Yale archives and began to plan for the 175th anniversary of his appointment.

In September 2016, an exhibition and six-month-long series of lectures reinvigorated the dusty legacy of one of the leading American Orientalists of his time. It also opened a window onto the history of Arabic in colonial and early America that predates Salisbury by almost 200 years.

The Christian Reformation in Europe in the 16th century stimulated scholarship of the Bible, including the study of ancient Hebrew, Aramaic, Chaldaic, Syriac and Arabic, all to better understand original texts. Harvard was the first to introduce this theologically driven study of Semitic languages in 1640, and it added Arabic while Charles Chauncy served as the university’s president between 1654 and 1672. Yale introduced Arabic in 1700; Columbia University in 1784; and the University of Pennsylvania in 1788.

“The earliest colleges founded in the us were intended to produce an educated ministry who were supposed to be able to read the Bible, and preferably early translations in Aramaic,” explains Benjamin R. Foster, Laffan Professor of Assyriology and Babylonian Literature at Yale.

“However, the practicality of life in colonial America was such that very few students were actually interested,” he adds.

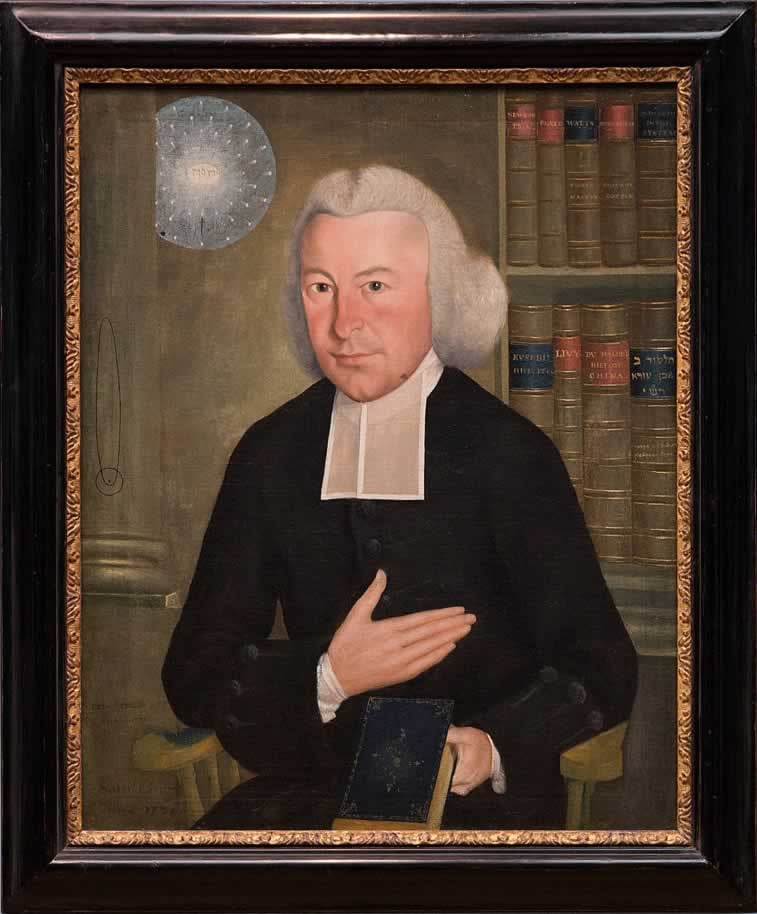

Ezra Stiles, an ordained minister who studied Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic, encountered this reluctance after he became president of Yale amid the American Revolution in 1778. “I have obliged all the freshmen to study Hebrew,” wrote Stiles in 1790. “This has proved very disagreeable to a number of the students.”

Semitic studies were a specialization at the graduate level in Europe and later spread through the us, explains Roger Allen, Emeritus Professor of Arabic Language and Literature at the University of Pennsylvania. Graduate studies in America, he notes, were influenced by the rigors of German scholarship and based on the German model, led in large part by the immigration of German scholars to the newly formed United States. Almost all the dictionaries and teaching anthologies at that time had been translated from the original Sumerian, Arcadian, Aramaic and Arabic into German. The old adage, jokes Allen, was that “the most important Semitic language then was German!”

Among these German scholars of Semitic languages was Johann Christoph Kunze, whose courses in Hebrew, Syriac, Aramaic and Arabic at Columbia University, beginning in 1784, failed to attract any students. Nevertheless, Arabic was introduced both at Dartmouth College and Andover Theological Seminary in 1807, Princeton Theological Seminary in 1822, New York University in 1833 and, in 1841, Yale not only offered courses but also made its historic appointment of Salisbury as the country’s first full professor in the field.

Unfortunately, to his lasting dismay, Yale students showed little more enthusiasm for Salisbury’s offerings than Columbia’s had for Kunze’s. He had only two graduate students prior to his resignation in 1856.

The very peculiarity of our national destiny, in a moral point of view, calls upon us not only not to be behind but to be even foremost, in intimate acquaintance with Oriental languages and institutions. The countries of the West, including our own, have been largely indebted to the East for their various culture; the time has come when this debt should be repaid.

—E.E. Salisbury to Yale faculty, 1848

Twenty-seven years later, at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Paul Haupt, a German Assyriologist from the University of Göettingen, found more success than either of them. In 1883, Haupt’s program in comparative Semitic philology became the model for other American universities at the time when interest in Arabic was shifting from a basis in theology to the language itself, “in order to learn about premodern history, culture, religion and society,” says Allen.

By the mid-19th to the early 20th century, more universities and theological seminaries began to offer Arabic. In 1900 Yale Professor Charles Cutler Torrey picked up where Salisbury left off, reinvigorating interest in Arabic-language studies and founding the first American center for Oriental research in Jerusalem, which continues to this day. At the same time, the growth in archeology triggered further interest in learning not just written Arabic, but spoken Arabic as well, including dialects. By 1937, 10 universities in the us offered Arabic, although only at the graduate level.

The aftermath of World War ii precipitated a new and urgent shift as the emergence of the us as one of two superpowers called for new international skills. “It was abundantly evident that America was falling very short on any kind of expertise about what was actually going on post-Ottoman Empire,” says Allen.

The us government enlisted renowned linguists to prepare textbooks and to create language training for military personnel. In 1947 classes in Modern Standard Arabic (literary Arabic) and dialects began at the Foreign Service Institute School of Languages in Washington, D.C., as well as at the Army Language School in Monterey, California. By the early 1950s, other government agencies such as the National Security Agency and the Central Intelligence Agency had established Arabic programs.

When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, in 1957, the Soviet educational system’s emphasis on science, mathematics and foreign languages was seen as the leading factor in its edge in space technology. In response, the 1958 National Defense Education Act (ndea) supported the study of these subjects in schools, and it identified five languages for priority funding: Russian, Chinese, Hindustani, Portuguese and Arabic. Title vi of the ndea supported new fellowships, instructional materials, summer programs, teacher-training workshops, research and more—many of which continue, in various forms, today.

From the private sector, a 1957 Ford Foundation grant of $176,500 funded an inter-university summer program in Near Eastern languages shared among Columbia, Harvard, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, Michigan and Princeton, with each university teaching Arabic on a rotating basis in the summers from 1957-1961. Extension of the grant from 1962 to 1968 added the University of California at Los Angeles, Georgetown University and the University of Texas at Austin. These grants not only helped to establish the increasingly widespread model of intensive Arabic-language summer programs (see sidebar below) but also generated new teaching methods.

“This was really the beginning of area studies with the idea being that Arabic should be taught as a language, not only in its classical but also in its contemporary idiom,” says William Granara, director of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “This was the new generation,” he adds. Thanks also in part to new vinyl and magnetic-tape recording technology, the audio-lingual method emerged at this time, and “it wasn’t just reading a dead text, it was interacting with a language.”

The 1960s brought further changes. In 1963 the American Association of Teachers of Arabic formed and began to professionalize the teaching of Arabic. A series of teacher workshops from 1965 to 1967 led to the publication of the textbook Elementary Modern Standard Arabic as well as a college-level Arabic proficiency exam. In 1968 a consortium of eight American universities founded the Center for Arabic Study Abroad.

The 1979 Carter Commission on International Studies and Foreign Languages marked the beginning of the proficiency movement when it concluded: “America’s incompetence in foreign languages is nothing short of scandalous and it is becoming worse.” This introduced an element of radical new classroom strategies. “It’s not texts anymore, its communications,” explains Allen, who became the national proficiency trainer in Arabic for the American Council for the Teaching of Foreign Languages from 1986-2002.

When Allen held his first workshop in Arabic proficiency methods at The Ohio State University in 1986, many of the leading Arabic scholars showed up, including Peter Abboud, Ernest McCarus and R. J. Rumunny. “Those guys immediately realized that what they had done in the 1960s and 1970s modernized the study of Arabic, but what they hadn’t done was to get entirely away from the grammar-based approach. What proficiency did was turn this whole thing on its head. They now had to figure out how to teach Arabic for communication purposes,” says Allen.

“Today, you want to prepare a student to deal with the realities of Arabic as it is used in the 21st century,” explains Professor Munther Younes of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. In contrast to Al-Kitaab, the most successful contemporary Arabic-language textbook, Younes fully integrates formal, written Modern Standard Arabic (fussha) with spoken Egyptian and Levantine dialects (ammiya). “This is what best serves the modern generation of students,” he says.

Arabic studies today are a far cry from their mid-16th- century beginnings as a tool to interpret Biblical texts. According to the Modern Language Association, Arabic is now the fastest-growing language studied at us colleges and universities. More than 35,000 students are enrolled in courses, a number that grew 126 percent from 2002 to 2006, and another 46 percent by 2009. Arabic is now the eighth most-studied language in the us and, as of 2013, 84 primary and secondary schools across the country offered Arabic-language classes.

“I was never really aware of the history of Arabic-language instruction in the us,” confesses Lizz Huntley, a lecturer at Cornell and former director of the Charlestown High School Arabic Summer Academy in Charlestown, Massachusetts. She recalls when she and the program’s founder, Steven Berbeco, were teaching a group of college students at the Harvard University campus. “When he told them that the first classes in Arabic began at Harvard, it was funny to see how the students all suddenly sat up a bit straighter, as though they realized that they were part of something much bigger than themselves,” explains Huntley. “It was wonderful to see them take pride in that history.”

About the Author

Krisanne Johnson

Krisanne Johnson is a Brooklyn-based photographer whose work has been exhibited internationally and appeared in magazines and newspapers such as the New York Times, TIME, and Fader. Johnson holds a Master’s degree in Visual Communications from Ohio University. Since 2006, she has been working on personal projects about young women and HIV/AIDS in Swaziland and post-apartheid youth culture in South Africa.

Piney Kesting

Piney Kesting is a Boston-based freelance writer and consultant who specializes in the Middle East.

You may also be interested in...

AramcoWorld Explores Universal Food and Cross-Cultural Identity

Food

History

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5&cw=480&ch=360)

Photo Captures Kuwaiti Port Market in the 1990s

History

Arts

After the war in 1991, Kuwait faced a demand for consumer goods. In response, a popular market sprang up, selling merchandise transported by traditional wooden ships. Eager to replace household items that had been looted, people flocked to the new market and found everything from flowerpots, kitchen items and electronics to furniture, dry goods and fresh produce.

Pearls, Power and Prestige: The Symbolism Behind Byzantine Jewelry

Arts

History

A 1,500-year-old gem-encrusted Byzantine bracelet reveals more than just its own history; it symbolizes an empire’s narrative.