I Witness History: I, Innocent Asp

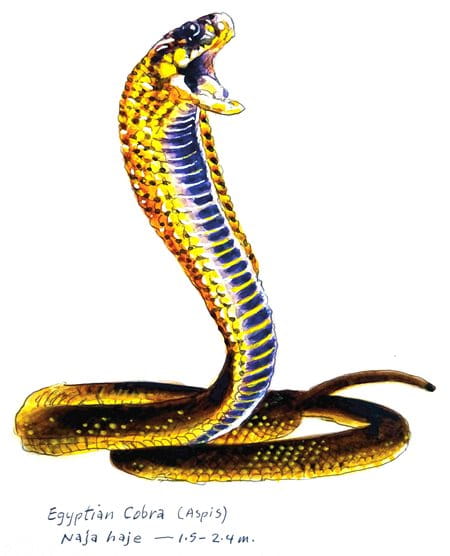

You do not know the real me. The demise of Cleopatra is but one of your many slanders against my kind. Even Shakespeare in Antony and Cleopatra called me a “poor venomous fool.” But let’s examine the facts: I, the Egyptian asp, Naja haje, did not kill the queen.

Hisssstory vexes me. The very sound of it sizzles on my serpent tongue, tasting of lies and hypocrisy. Do not speak to me of apples and Eve, or of mad Medusa whose gaze turned onlookers to stone. Why should I not be angry? I am despised as a primal, unhuman creature living without arms or legs, eyelids or eardrums. I am scaly and bladderless. I breathe one-lunged and have no mewling cry. In many cultures of your kind, we snakes are maligned as liars, our forked tongues equated with falsehood. In your language, “to snake” means to steal, anyone “crooked” is “a snake in the grass,” and somebody cruel is “cold-blooded” and “mean as a snake.” I symbolize sin and treachery more than any other creature that creeps or crawls, according to the one that “stands tall” and walks “upright.” From where I lie, it’s low time I set the record crooked.

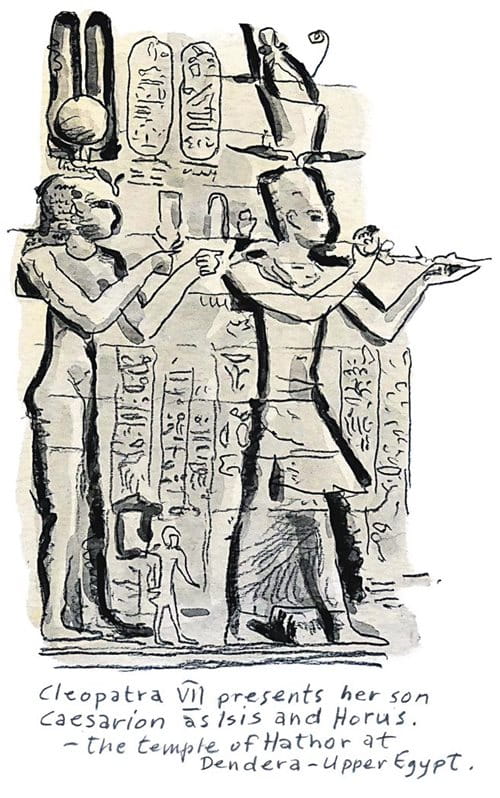

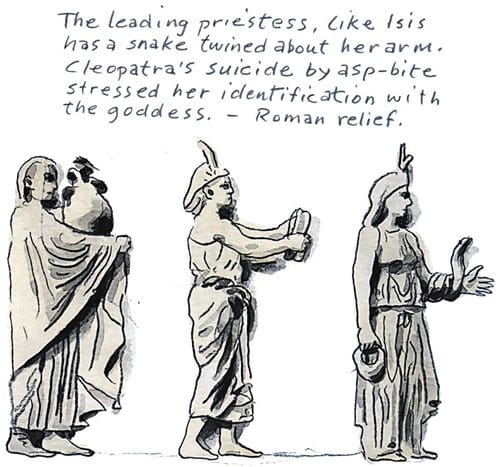

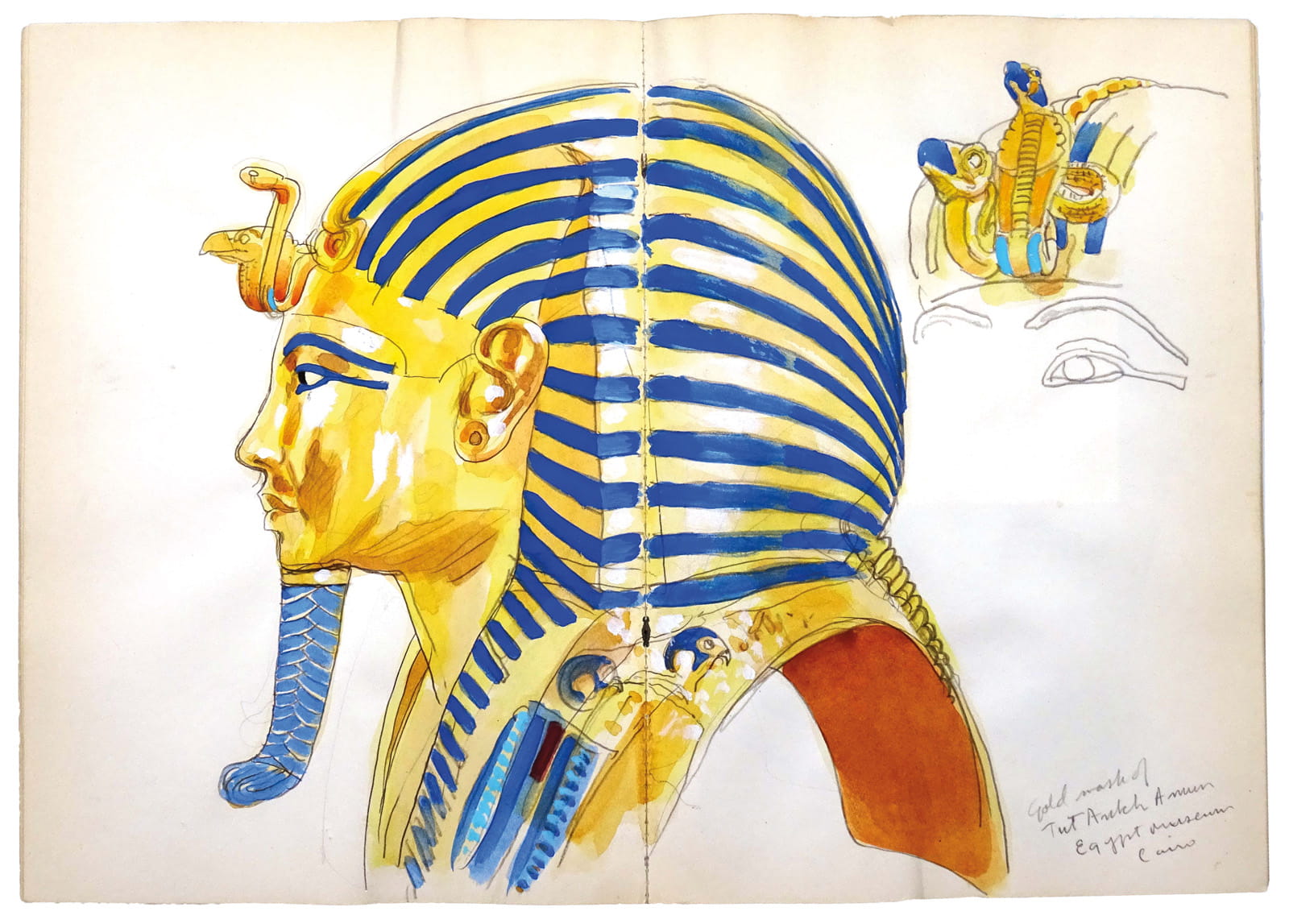

The bones of my kin were found in jars some 4,300 years old buried in a temple at Qal‘at al-Bahrain. I invite you to recall my noble role as Mucalinda, Buddha’s half-human, half-cobra Naga. Do not forget I am the rainbowed Aidophedo of the Ashanti of West Africa, the many-headed Shesha of Hinduism and the cosmic Quetzalcoatl of Meso-america, and that for centuries I gazed from the brows of the pharaohs as the sacred serpent-goddess Uraeus of Egypt. I was the wise Wadjet of the Nile Delta and the silent Meretseger, guardian of the dead at Thebes. I was the good serpent Mehen who fought off the evil Apophis every night when the sun god Ra sailed through the dangers of dark. I attended dear Isis and, so the Egyptians have said, fathered Alexander the Great. And still, I crawl accused of killing Egypt’s last great queen, Cleopatra vii.

Your high culture, alas, is no better than your consumer culture. Canvases depicting poor Cleopatra’s demise, with me as the obvious villain, clutter your museums. Painters Andrea Solari and Peter Paul Rubens showed me long and writhing; Guido Reni and Giovanni Lanfranco painted me wormishly tiny. Claude Vignon and Augustin Hirschvogel gave me the head of a dragon, and Benedetto Gennariand Giovanni Francesco Barbieri brushed on red to show blood dripping from my fangs. But this is not the real me.

This staged demise of Cleopatra and her handmaidens is part of a larger plot to ruin me. Even Shakespeare’s stage directions stated for Antony and Cleopatra that Cleopatra “applies an asp,” as if I were some inanimate apparatus. I find these stage directions as demeaning as the dialog that calls me a “poor venomous fool.”

Cleopatra began as a pawn in this game of Roman imperialism. Civil war forced her to take sides, first with Julius Caesar and then with his general Marc Antony.

You see, I, the Egyptian asp, Naja haje, am the victim of overwrought imaginations. I did not kill Cleopatra. Not in Shakespeare’s way or any other.

Let’s examine the facts. Her Highness ruled Ptolemaic Egypt at a time when the Romans were just beginning to take over the eastern Mediterranean world. The mighty queen began as a humble pawn in this inexorable game of Roman imperialism, and civil war and forced her to take sides, first with Julius Caesar and then with his general Marc Antony. She even married Antony to secure the preservation of Egypt, if not as an independent nation, then at least as an equal partner. You may not realize how close she came to success. But in a single battle all was lost. Caesar’s adopted son Octavian, who would become later immortalized as Emperor Augustus, prevailed at the Battle of Actium in the Ionian Sea in 31 bce against the combined forces of Antony and Cleopatra, spelling the end of both the Hellenistic period and Ptolemaic Egypt. Upon losing, Antony committed suicide, whereas Cleopatra was captured and held as a prisoner of war by Octavian’s forces in Alexandria. It is somewhere in this part of their story I usually make my entrance.

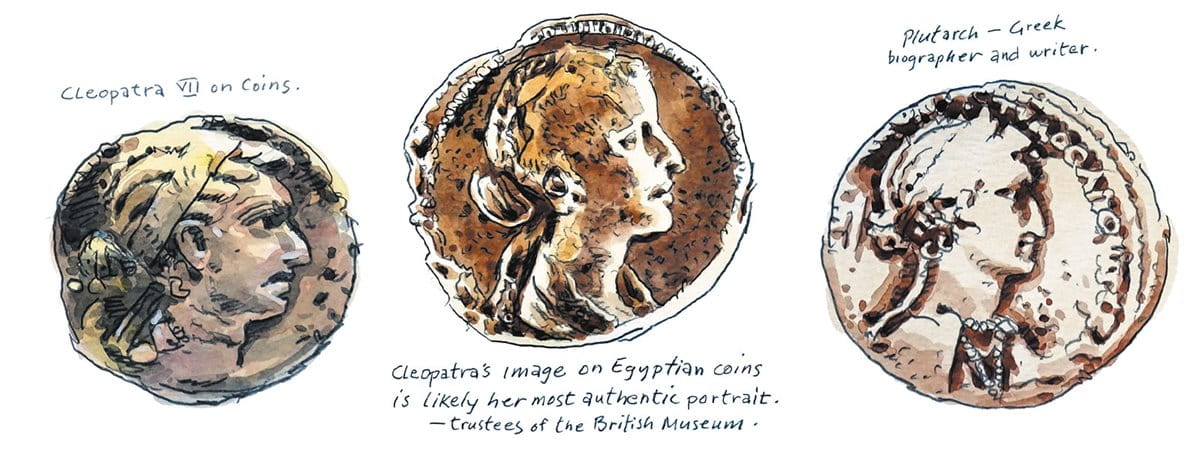

According to the Greek geographer Strabo, who may have been in Egypt at the time, the queen killed herself secretly while in Octavian’s custody. Strabo reports that two versions of her suicide were circulated: one, that she suffered at my fangs, while the other claimed she poisoned herself. Strabo himself made no choice between these two theories. Then a few Latin poets, unhindered by facts, scribbled some lines on the subject. They all preferred the more sensational asp story, of course. Patriotic and well-paid by Octavian, these Romans maligned Cleopatra too, calling her regina meretrix, harlot queen, and dedecus Aegypti, shame of Egypt.

In the second century ce, the Greek writer Plutarch penned a detailed rendition of Cleopatra’s last days. Plutarch states that he consulted the published memoirs of Olympus, Cleopatra’s personal physician. Now this sounds promising, until you realize that this doctor was permitted to live—and write—only because he served Octavian. This is the testimony of a tainted witness who claimed that after the death of Antony, Cleopatra became as unhinged as a serpent’s jaw. As her captor, Octavian allegedly did everything in his power to keep the queen, whom Plutarch insists grew demented, from hurting herself. When she tried to starve herself, Octavian could find no other remedy than to threaten her children. This was powerful leverage: Cleopatra had a son with Julius Caesar and three younger kids with Antony.

Plutarch relates that these threats convinced Cleopatra to cooperate. A few days later, Octavian paid her a visit. He found her sickly, unkempt, and still a bit wild-eyed. Yet despite her condition, she hoped to sway Octavian with her beauty and charm. This naturally failed with a man as incorruptible as Octavian (I would wink here if I had an eyelid), so Cleopatra caved and claimed that everything was Antony’s fault. When Octavian countered her excuses, she next tried pity, prayers and promises. In the end she managed only to convince Octavian she wished to live. This made it easier to arrange her own death, having suddenly forgotten the threats against her children.

Octavian had no suspicions when Cleopatra asked whether she and her female attendants might offer a sacrifice at Antony’s tomb. Clutching the ash-urn of her beloved Antony (other sources say he was embalmed), Cleopatra supposedly confided to his cinders her trepidation at becoming a trophy in Octavian’s triumphal parade. She could not bear the humiliation of marching in chains through the streets of Rome. Here, at last, Plutarch gives us a motive for her suicide, thanks to a supposed confession heard by no one who lived to reveal it.

Though large, we Naja haje do not store enough neurotoxin to kill three of you upright mammals in quick succession.

Next, we need means and opportunity. The crafty Cleopatra bathed, dined and then sent Octavian a suicide note while awaiting delivery of a little basket of figs for dessert. This request for room service provided the opportunity to smuggle past her derelict guards the means of her crime—me. Plutarch declares that Octavian’s sentinels checked the basket and did not notice me inside. Now look at me and pay heed to my sinuous swaying swagger and large, unblinking black eyes. We asps average a meter and a half in length. Our heads are large and our snouts broad. Not see me in a snack basket? Yet there I reportedly lay undetected, curled tightly at the bottom, waiting patiently to wipe out three adult women in a locked room? Does that make sense to anyone?

I could not have done it. Though large, we Naja haje do not store enough neurotoxin to kill three of you upright mammals in quick succession. Death could take hours, yet Cleopatra had only minutes before her suicide note brought Octavian running to the scene. Furthermore, Plutarch admits that no trace of me was ever found inside the sealed room—there were no smoking gums. The suggestion that I somehow crawled out a window and escaped along the beach toward the sea is ludicrous.

Even crazier are the specific reports of what Cleopatra said and did inside that closed room, where the only witnesses died with her. Who could have known that I was ever there, that the queen spoke to me before I bit her arm or that she had to provoke me with a golden spindle before I would lunge at her? No woman intent on suicide would entrust her death to me. I could bring nothing to the occasion but a hundred possible misadventures. And for what? She was already a deity; I could do nothing to render her more so.

No matter, my accusers could not push my writhing image out of their minds. When Octavian paraded an effigy of the queen in his triumphal parade, the crowds fixated on a copy of me clinging to her body. Onlookers assumed this to be an official reenactment of her demise, but it may simply have been an Isis snake bracelet. No wonder, after spinning this gossamer of lies Plutarch confesses, “Nobody really knows what happened.” He adds that a concealed poison may have actually done the deed.

A gossipy contemporary of his, a writer named Suetonius, introduced the bizarre anecdote of the Psylli (pronounced, appropriately, like your word “silly”). These were a North African Berber tribe of professional venom suckers who could be summoned to save snakebite victims. Though it was considered heroic work, the job training was brutal. Only men who as children had survived being tossed into a snake pit could take up this trade, so there never were many of them around. Suetonius says Octavian deployed the Psylli in a vain effort to revive Cleopatra.

A century later the Roman Cassius Dio embellished the story even more. He describes with increasing detail the queen’s efforts to seduce the ostensibly virtuous Octavian, who knew better than to look directly at his alluring captive. According to Cassius Dio, she shamelessly tried everything: provocative clothing, sweet looks, a lilting voice, some tender weeping and even old love letters from Caesar, Octavian’s adoptive father.

Spurned and fearing the ignominy of his triumphal parade, Dio’s Cleopatra plotted suicide as Octavian posted guards and a Psylli rescue squad to stop her. Now think about that. Having these venom-suckers on standby would mean that Octavian antici- pated not only me, but also my getting past his guards, who were therefore on alert for a smuggled snake. Since I alone could not have quickly killed all three women inside the chamber, several of us would have needed to slip past Rome’s equivalent of the Keystone Kops—coming and going. Yet Dio casually admits that no one could really know what happened to Cleopatra.

The medical writer Galen mentions the possibility that Cleopatra bit her own arm and then smeared the wound with smuggled venom. This way, I get blamed even in absentia for her death by self-fangulation. Galen must have liked the idea that Cleopatra never actually handled me, for he suggests that if I were there on the scene, I would have been a spitting cobra. What an imagination! The good doctor also claims to know that Cleopatra had her hair and nails done by two attendants, both of whom I spit to death before turning my wads on the queen.

One murder rap apparently deserves another and another. In the 10th century ce, the Baghdad-based historian al-Mas‘udi expanded my killing spree beyond Cleopatra and her female servants. At least he didn’t mutilate her character like the Romans. As with many scholars of the medieval Arab world, he does sing her praises, calling her a “princess versed in the sciences, given to the study of philosophy … [having] composed on medicine, charms and the particulars of other natural sciences.” But al-Mas‘udi cruelly paints me as a merciless savage, even claiming I murdered Octavian as well. That’s an especially interesting fantasy, a bit of alternative facts in which the familiar Western obsession with Octavian’s triumph and empire-building is cut short by yours truly. For you see, al-Mas‘udi alleges me to be a rare two-headed serpent from Hijaz (in western Saudi Arabia) that could spring so fast and so far that my victims never knew they had been bitten. So, after instantly dispatching the women in Cleopatra’s chamber, I hid among the ornamental plants until Octavian entered the room. My stealthy attack paralyzed his right side, giving him just enough time to dictate a Latin poem before his demise. The Romans always get the last word.

Well, not always. One of your poets, Ahmad Shawqi of Egypt, is one of the few who ever came to the queen’s defense. In 1927 he turned the tables—better late than never—charging the Romans of recording history “in a fictive style, in which the Caesars of Rome got all the glory … while the poor Egyptian queen, Cleopatra … got nothing but a heap of accusation, sins and curses.”

Here’s what I think really happened. Start from the fact: In August 30 bce Cleopatra died in the custody of Octavian, her enemy. I would not be surprised if he executed her and clumsily covered up the crime as a suicide-by-asp. Octavian controlled every source of information about Cleopatra’s fate. He shaped his official version with loyal assistance. He had no fear of contradiction or correction. All the Psylli stories about his efforts to save the psychotic queen masked his true intentions—he wanted her dead. Why? Quite simply because Ptolemaic queens were a dangerous commodity and very difficult to be rid of safely. She—the mistress of his father, the wife of his enemy and the mother of his last rival—must never tell her side of the story or be given the chance to charm a world that might be prone to forgiveness. Octavian’s alleged urge to display the captive Cleopatra in his parade was a ruse; he wanted no such thing. Just a few years earlier, Julius Caesar had held such an event in Rome. The spectacle, as anticipated, delighted the crowds—until they saw a Ptolemaic queen marching in chains among the prisoners. That was Arsinoe iv, Cleopatra’s half-sister, and the Romans reacted so vehemently against her humiliation that she had to be released to placate public sentiment. Could Octavian risk a similar outcome with Cleopatra? He had made his fortune fighting to save his world from her, and it would be devastating to his ambitions if she appeared in Rome as anything less than the evil, crazy, seductive monster of his propaganda. Letting her live was an indulgence he could not afford.

“A princess versed in the sciences, given to the study of philsophy ... and the particulars of other natural sciences.”

—al-Mas‘udi

But killing Cleopatra had to be carefully arranged. Octavian had ample opportunity, means and motive to eliminate the queen of Egypt before she could arouse anyone’s sympathy. To launder his image, he had to sully hers. His plot achieved its purpose so well that even now, thousands of years later, your visions of Cleopatra—your stereotypes as you call them—voluptuous, vain, promiscuous, treacherous, manipulative, excessive and need I go on—were fostered by Octavian to advance history. His victory rested upon her villainy in the court of public opinion.

That is the same court that has been convicting me of murder over two millennia. Only a few experts, mostly new ones over the past decades, have come to my defense, declaring my innocence with almost unhuman fairness and reason. Still, not many of them are willing to point an accusing finger at Octavian as I would do if I had one. Murder is a hard charge to prove when a suspect owns or eliminates all the evidence. So be it. Believe what you want about Cleopatra’s last moments. Just leave the hiss out of history. Like you, I have my suspicions. And like you, I wasn’t there.

You may also be interested in...

“Old Bridge” Story Inspires Lessons in Writing and Community History

History

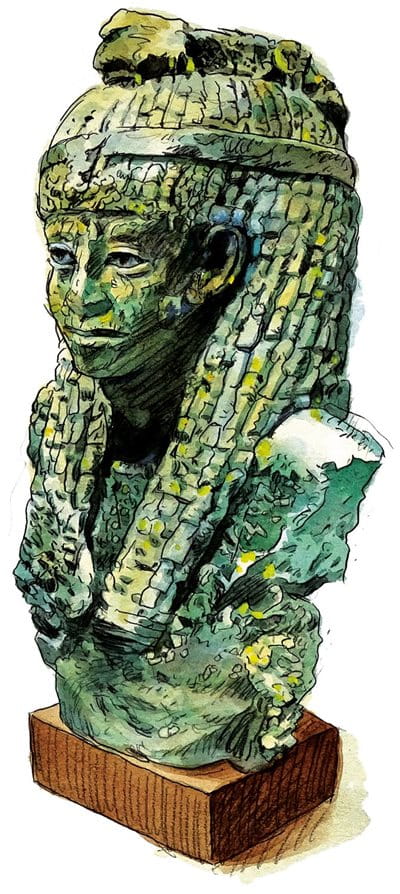

See How Researcher Zainab Bahrani Rethinks Narrative of Ancient Art

History

Arts

Zainab Bahrani of Columbia University photographs ancient statues and reliefs carved into the rocks of remote Iraq to create a database for conservators and scholars. The effort is “decentering Europe from histories of art and histories of archaeology.”

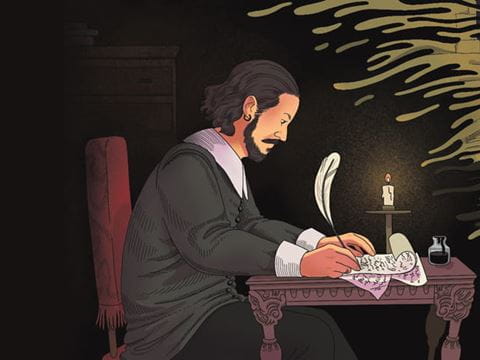

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.