The Westward Journeys of Buttons

We all use them. Most fasten; some decorate. A search for origins points toward the Indus Valley and China. By the Middle Ages, buttons reached Europe along with other garment techniques and fashion influences from lands east. Their stories are as interwoven as the textiles they make possible and as varied as their infinite designs.

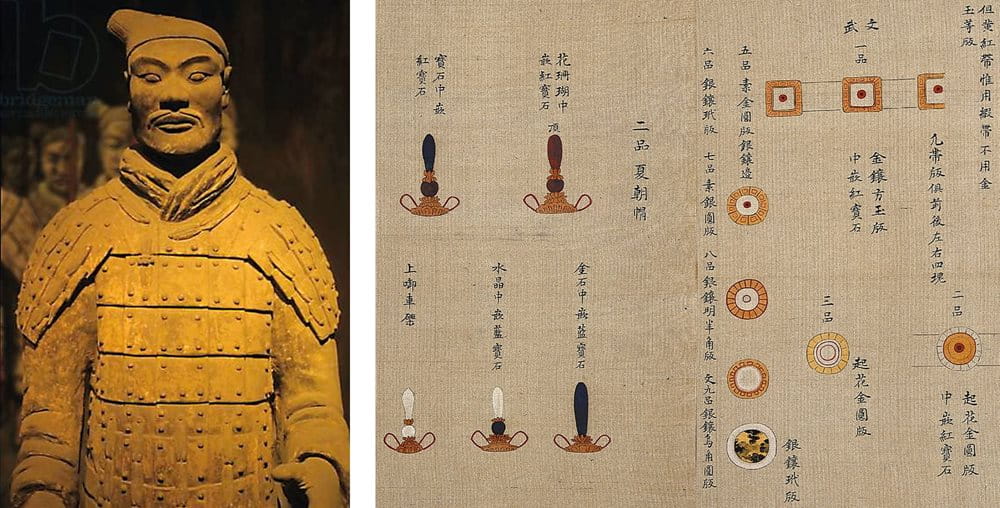

Second row This cast bronze button is of Mongolian origin, from the fifth to third century bce; a simple Phoenician shell button was made from the eighth to second century bce; the flat side of this lumpy faience button makes it possible it served also as a seal in Egypt between the sixth and first century bce; from northern China, this button was made of gilt cast bronze between the first century bce and first century ce.

From the rear storage room of her country cottage outside Budapest, Hungary, Sylvia Llewelyn holds up a framed display of antique buttons as if it were a portrait of a family member known for telling good stories.

“This one is from China, and it’s made of jade. This one is glazed ceramic; this one is glazed turquoise. This one is made from apricot nut. You see this one here that looks like a cherry tomato? This is carnelian, the second hardest stone to jade, and it’s about 500 years old,” she says, moving through her 4,000-piece collection, some of which are up to 1,500 years old.

An antiques and art appraiser originally from London, Llewelyn is also the former owner of Old Buttons Shop in her town of Ráckeve. She is also the author of Old Buttons (Anno, 2011), a book of rare and artful buttons around the world.

“I remember a lady asked me once to appraise some old buttons she found in her mother’s sewing box,” she recalls. “They were French Revolution buttons, a set of six, and each was different, each with secret symbols supporting the Revolution.” Owning such buttons, she says, “may have saved you from having your head chopped off.”

For most of us, buttons are so ordinary we tend not to think about them until one falls off. It was not always this way, of course. From origins in Asia and Egypt, for more than 5,000 years people have traded buttons and innovated with materials, designs, techniques and functions in every direction, altering how we dress and how we express ourselves and our cultures.

Above, top row Also from China comes a cast bronze button adornment, from the Han dynasty, made between the second century bce and second century ce; also of bronze, an openwork ornament found in Korea was made between the first century bce and the ninth century ce; a polished shell-disc button from Sasanid Persia, dated from the third to seventh century ce and, shown under it, an English Roman loop fastener of copper from the first or second century ce.

Second row With a dot-in-circle design, a Sasanian button dates from the eighth to 10th century ce; a spherical cloissonne enamel and gold button comes from 10th-century ce Byzantine Bulgaria; a flat-ended bronze button from seventh-century ce northern France; a button or bead from ninth- or 10th-century ce Nishapur is made of bone.

Lower left A set of 16 small buttons, cut and hammered in Afghanistan from debased gold in the late second century ce.

The earliest object that may have been a button—what archeologists call a perforated shell disc—could have been used as a button or pendant. Dated to about 7000 bce, it was excavated from a burial site at Mehrgarh in the Indus Valley in present-day Pakistan. Drilled with a hole, it could have been sewn onto clothing. It is made from a type of conus shell, and shell-working was an important craft at the site, which is one of the world’s earliest-known locations of organized human settlement along with others in Mesopotamia, China and Egypt. Other Indus Valley sites, especially in the period 2800–2600 bce, have yielded similar items.

“If they were sewn on clothing or used some other way, we cannot say for certain whether they were for utility or for decoration,” says J. Mark Kenoyer, a professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who has specialized in the Indus Valley Civilization sites for more than 30 years. “People have been putting objects on strings and using them as decoration since early man.”

As for these being “the oldest,” he adds that “we always think it’s the first until we find something else that’s earlier, so I never like to use that term.”

By 4000–5000 bce, the excavation finds begin to show some carved and decorated discs of bone, ivory, clay and stone that have two holes in the center or a boss in the back, which adds to the evidence that these may have been sewn onto something.

In China, objects not unlike those found in the Indus Valley have been found at Bronze Age sites. The earliest-recorded button in China dates to about 1000 bce during the Zhou Dynasty, and it is a knot-and-loop button, in which both button and loop are fashioned with fabric. These are still in use on modern Chinese garments such as the qipao or cheongsam, a fitted dress for women.

It was not until the Islamic conquests in Central Asia in the late seventh and early eighth centuries ce, and over the later centuries of trade along what came to be called the Silk Road, that the knot-and-loop button closure appears to have made its way West, along with paper and other cultural artifacts.

In this way, it is most likely that buttons reached Europe via the Mediterranean in the course of the great cross-cultural exchanges triggered by the Crusades starting in the late 11th century, which led to the West’s adoption of innumerable innovations. Arab geographer Ibn Jubayr, writing about his travels from 1183 to 1185 ce, comments on Christian women adopting Muslim fashions, notably in Sicily. Among these were head-coverings such as the wimple still worn by Catholic nuns and the dramatic, conical hennin, clearly derived from the tantur of Syria-Lebanon and, for both sexes, long, kaftan-style coats with hanging sleeves. Although Ibn Jubayr does not specifically mention buttons, the caftan was often buttoned all down the front. It was known as caban or turcha, and as it came west, it became the first real European coat, the descendants of which form an important part of our wardrobes today. These borrowings came through merchants not only from the wares they brought back but also because they themselves wore and became accustomed to “oriental” clothes on their travels, often in the interest of safety during times of conflict.

As buttons gradually became useful as well as symbolic, it is worth thinking back for a moment about the options for clothing before buttons-as-fasteners. The most obvious answer is drapery, as in the case of classical dress, or even the modern sari. The first of these was held, where necessary, with large decorative fibulae fixed below the shoulders, still to be seen in the traditional North African Amazigh tizerai. Other garments such as tunics were pulled over the head and fastened—or attached—with points and laces. Sometimes, in order to obtain close fit, the wearer was stitched into a garment.

The advent of the button as a fastener shows in the fashions preserved in European paintings: From the later Middle Ages, dresses fit women closely, showing off the shape of the body and sleeves, again apparently imitated from the East, that could be unbuttoned to free the forearm or when the long sleeve was inconvenient or hot.

Sometime earlier, perhaps around the 13th century, the buttonhole was developed. This made possible really close-fitting garments, which were especially useful in colder climates. The buttons of the period generally had a shank on the back with a hole for sewing, leaving the surface of the button free for a vast range of decorative options.

Archeologist and historian of textiles and dress Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, director of the Textile Research Centre in Leiden, The Netherlands, has spent years on excavations in Egypt looking for early textiles and clothing materials. The earliest forms of buttons there, she says, date to around 1400 bce, when two ties on the neck openings of clothing evolved into something like the knotted button and fabric loop.

“Looking at ancient Egyptian clothing, they had cloth buttons. Thread was used to create a button on a garment with a matching loop on the other side,” says Vogelsang-Eastwood, who earned her doctorate in archeological textiles from The University of Manchester. “We didn’t start seeing clothes buttons as a separate item sewn on garments until the 1300s, 1400s.”

In Egypt, too, buttons were, like cloth itself, a sign of wealth. The more cloth a person wore usually meant they could afford it, so hemlines were related to income.

“The more cloth you wore, the higher your status,” she says.

So too with buttons as they appeared in Europe, she continues. They would have been individually designed and usually made of fine metal or precious stones, often by a jeweler or a specialized button maker. (A Paris document dating to 1292 mentions permits for a button maker.) They would have then been sewn onto a garment or fabric by a tailor or a seamstress. The wearer of the button-adorned garment may have needed an assistant to help them into and out of the outfit, which means they would have to be able to afford this level of service. Sometimes, however, buttons were purely decorative, even on shoes, cloaks, coats and dresses, appearing on sleeves or areas where buttons were showcased and not used as a closure—a practice still often found on the sleeves of Western men’s suits.

“Most of the buttons were valuable, and they were usually cut off one garment and put on another. You showed your prestige with buttons,” she says. “The idea that buttons are nothing is a 20th-century concept with the onset of plastic.”

Among innumerable styles of buttons, including those designed to conceal secret information, contraband (or even poison), metal buttons became popular, especially for military uniforms—remember Llewelyn’s appraisal of the French Revolution buttons? In the late 17th century, this fashion appears to have spread eastward, from France to Turkey in the late 17th century. During the Napoleonic period, buttons were found on Ottoman uniforms with a variety of crests and insignia, as elements of Western dress were adopted there.

In a much-debated political mystery attributed to a particular Turkish military button, King Charles xii of Sweden was fatally wounded by a gunshot in battle in 1718. It is thought that the fatal bullet was fashioned from the melting down of the king’s own Turkish-made metal buttons—that is, from a button taken from one of the king’s own garments. The implication, of course, is that such a button could only have been acquired by someone close to the king—an act of treason rather than a casualty in battle. The story may never be settled, but melting buttons was common.

“If soldiers ran out of bullets, they would melt the buttons down,” says Llewelyn. “The higher-ranking officers of the 17th and 18th centuries would have had brass and gold buttons, and remember silver wasn’t that valuable in the old days,”

Fascination with Muslim fashion continued, and as the Ottoman Empire’s power and wealth grew, it became a major source of European inspiration. Europeans (as well as Americans) regarded eastern luxuries as the height of elegance, from sumptuous hi’lat or “robes of honor” to what became the priest’s cassock—a term that came from Turkic kazak in the early 17th century for a robe fastened from neck to ankle with numerous buttons.

This is a style that can still be seen, especially in Morocco, in the long lines of buttons, fashioned with classical needlework, that run down the fronts of traditional djellabas or kaftans. A formal one can have hundreds. Made with a needle and thread over a paper core, there are today some 40 designs being produced, and each takes between four and 10 minutes to make, depending on the design and the experience of the craftswoman. The pattern names often refer to the shape of the button: acorn, jasmine flower, etc. Button making remains a useful supplementary source of income for women, some of whom have formed independent marketing cooperatives, which by eliminating middlemen increases their income and, consequently, opportunities for their children.

By the early 1900s, while their distant ancestors still lay undiscovered in the Indus Valley, shell buttons found a new center of production: the town of Muscatine, Iowa. Situated along the Mississippi River in the us and naturally supplied by beds of freshwater clams and mussels, Muscatine at its height mass-produced some 1.5 billion “pearl buttons” a year. That same pearlescent quality endures today as one of the most common colors of button, though now made from plastic.

You may also be interested in...

Orion Through a 3D-Printed Telescope

Arts

With his homemade telescope, Astrophotographer Zubuyer Kaolin brings the Orion Nebula close to home.

Spotlight on Photography: Drinking in Türkiye’s Coffee Culture

Arts

Egyptology Today: A Conversation With Egyptian Archeologist Monica Hanna

History

Q&A

Until recently, Egyptian archeological sites were filled with foreign archeologists excavating prized treasures from the country’s ancient past.