For the Love of Reading

From its first read-aloud in Jordan in 2006, We Love Reading has become one of the world’s most-recognized nonprofit organizations encouraging reading among children. Behind its success stand more than 7,000 local volunteer “reading ambassadors”—mostly women—in 61 countries and its founder, a scientist whose own four children inspired her.

It was a perfect Saturday in Amman, Jordan, warm and sunny, and all 6-year-old Layan Al-Sweilemeen wanted to do was play with her friends. Her parents, however, had something else in mind. The imam at their local mosque had invited families attending Friday prayer to return with their children the next day for a new community read-aloud story program.

Fourteen years later, Al-Sweilemeen recalls how that day she and her younger brother reluctantly joined a couple dozen neighborhood kids at the mosque.

“There was this lady wearing a funny hat, who we only knew as ‘the hakawati,’” says Al-Sweilemeen, using the Arabic word for storyteller. “She read us several stories in all these different voices and tones. It was really interesting,” she recalls. At the end each of the children received a book and a promise of more stories in two weeks’ time.

The lady in the hat was Rana Dajani, a professor of molecular cell biology at the Hashemite University in Jordan and, as of that day, February 11, 2006, founder of We Love Reading (WLR), which translates in Arabic as nahnu n’hibu al qira’a.

Al-Sweilemeen, now a student at the University of Jordan, remembers that she continued to attend the story sessions led by Dajani and other “WLR ambassadors” until she was 9 years old. Although her parents had a library at home, she says, it didn’t include children’s books. She credits WLR with sparking her own passion for learning through reading. Al-Sweilemeen admits, however, that she never imagined how much WLR would grow. “You wouldn’t think something as small as a local reading circle would blow up and go all around the world,” she notes.

Today 60 countries beyond Jordan host WLR programs including most in the Middle East and others throughout Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. By 2019, 4,370 WLR ambassadors and approximately 7,500 trainees had led some 152,300 reading sessions for more than 447,000 children worldwide. In addition, true to Dajani’s goal, 4,300 WLR libraries have opened, each one a place where trained volunteers read aloud and exchange books with children.

Since 2011 WLR has worked with Jordanian authors and illustrators to produce 32 children’s stories for ages 4–10, and WLR’s ambassadors have distributed more than 261,000 copies. The stories all touch on real-life themes, from the fundamentals of friendship and empathy to countering bullying, protecting the environment and adapting to refugee life and disabilities.

This was quite a leap from the early days. Then an associate professor at Hashemite University, Dajani says she first spent three years spreading word of WLR neighbor to neighbor and publicizing it with radio ads and leaflets in local parks—all with the help of her family.

“Rana’s energy vibrates,” says her husband, former WLR CEO Mohammad Awad. “She not only has the energy; she believes that things will always work out.”

The oldest of nine children of Palestinian and Syrian heritage, Dajani was only 16 when she enrolled in the premed program at the University of Jordan. In 1999, as a young mother of three girls and a boy, she received a Fulbright Student Grant to pursue her doctoral degree in molecular cell biology in the US at the University of Iowa. By her early 40s, she had become the world’s leading expert on the genetics of Jordan’s Circassian and Chechen populations. In 2015, Arabian Business named Dajani one of the “100 Most Powerful Arab Women,” and that same year, the US State Department Hub for the Middle East and Africa inducted her into the Women in Science Hall of Fame.

“As a scientist I feel a strong sense of responsibility toward all of society to help develop solutions for today’s most pressing problems,” wrote Dajani in her book, Five Scarves: Doing the Impossible—If We Can Reverse Cell Fate, Why Can’t We Redefine Success? (Nova Science, 2018). “But I’ve always wanted to have a broader impact beyond the walls of the university. It was this aspiration that eventually led me to found a program that has become one of the most important initiatives of my life—We Love Reading.”

The seeds for WLR had been planted long ago in her youth. “I was a bookworm,” she noted. “In our home, my parents assembled a library that covered a long wall from floor to ceiling with books of all kinds in English and Arabic. I devoured every last one of those texts while still a young girl. I read everywhere.”

When Dajani and her family moved to Iowa City in 2000 for what would become five years, their four kids spent hours after school at the city’s public library, where they took part in read-aloud sessions and children’s book groups. Dajani was so impressed that when it came time to return to Jordan in 2005, she expressed her gratitude to the library in a poem that was published in The Daily Iowan newspaper:

Can I imagine a life without the Iowa City Library? The excitement of finding a book to read … The quickening of the heartbeat at the thought of finding a book long sought. … But wait … I have learned creativity so I will create wherever I go my own library that will grow and mature with my family in the fertile soul of my land in Middle Eastery.

Back in Amman in December 2005, Dajani noticed that despite Jordan’s 98-percent national literacy rate, it was rare to see children or adults reading on buses or in public. Libraries were few and their hours were short; none offered activities for children.

“Early-childhood-development research underscores the impact reading has on brain development as well as on social skills, especially if it is introduced before the age of 10,” she says.

Her desire to promote reading in Amman became a family project. Family discussions led to a plan to attract neighborhood volunteers, teach them read-aloud storytelling techniques and help them set up informal children’s libraries.

Her three daughters helped her choose books and arrange the reading sessions. They also took turns reading aloud to children. They built WLR’s first website using a logo the family created one night at the kitchen table. Today Sumaya, Amina, Sara and their brother Abdullah are all young adults who continue to be WRL advisors and fundraisers.

At first it was difficult to attract volunteers and convince anyone in her community that a home-grown project could make a difference. Yet the numbers of children attending her readings continued to rise, and kids began to ask their parents to read to them at home. Local libraries reported a five-fold increase in book-borrowing by families.

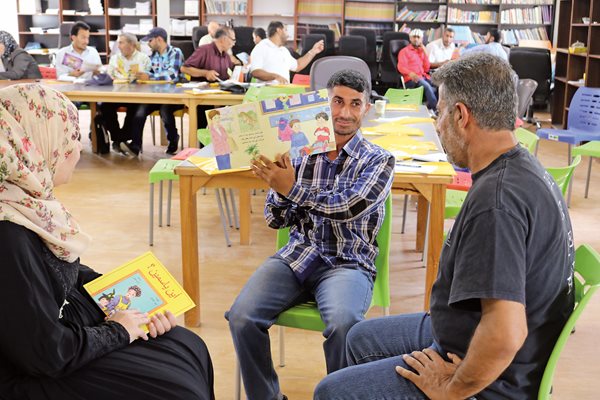

In 2009 the New York–based foundation Synergos presented Dajani with its Arab World Social Innovator Award. Dajani used its $34,000 grant to offer free two-day training workshops, and she hired Palestinian artist Denes Assad to teach the art of storytelling. She purchased 25 books for each newly trained ambassador and enticed the first volunteers to attend with an offer of free transportation and lunch.

One volunteer, recalls Dajani, was a woman about 70 years old from a town outside Amman. “She was illiterate, but she still wanted to take the training, which is oral and very interactive. Afterwards, she went home and enrolled in a literacy course. Two months later she came back and said, ‘I’m ready!’ We gave her the bag of 25 books each ambassador receives,” says Dajani, smiling. Back home, the woman started a reading circle of her own.

“Once people see how important WLR is, they will do whatever it takes to become an ambassador,” says Ghufran Abudayyeh, who has worked as WLR’s training and communications officer since 2015. While encouraging the pure love of reading is WLR’s main goal, she adds, “it’s also about the empowerment of women in their local settings once they become ambassadors. When they see the impact they have on children’s behavior by simply reading to them, they start believing in their own ability to do more.”

By 2010, ambassadors were leading WLR groups across Jordan, and word too was spreading beyond, as WLR projects took off spontaneously in both Thailand and Kazakhstan. Dajani registered WLR with the Jordanian Ministry of Culture under a new umbrella NGO she named Taghyeer (Arabic for change).

In 2013 the organization counted 10,000 children participating in storytelling and reading sessions. It was chosen as the “Best Practice” by the US Library of Congress Literacy Awards Program. This became one of many awards WLR has received over just a few years, including the King Hussein Medal of Honor, the UNESCO International Literacy Award for Mother-Tongue Education and the UN Science, Technology and Innovation Award.

Two years later WLR received $1.5 million from the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and $2 million from the US Agency for International Development (USAID). On October 1 of this year, acknowledging the value of the WLR program to refugee families in Jordan and the wider Middle East and North Africa region, the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) named Dajani a regional winner of its annual Nansen Refugee Award.

“Part of WLR’s success is ownership,” explains Awad. “It’s not us. It’s not a trademark or an institution. It’s the people.” Ninety percent of the ambassadors are women, he explains, from ages 16 to 80. All ambassadors receive encouragement to train others in their communities.

Antje von Suchodoletz, an assistant professor of psychology at NYU Abu Dhabi, has been part of a team studying the impacts of WLR. The research, in conjunction with Randa Mahasneh at Qatar University (Doha) and Ross Larsen at Brigham Young University (Provo, Utah), so far points toward small but statistically meaningful increases in reading attitude scores and reading practices among WLR children: At all ages, WLR girls and boys outperform non-WLR peers.

A study published this year by Dajani together with Alya Al Sager, Diego Placido and Dima Amso, Ph.D., looks at how WLR’s read-aloud method influences children’s executive functions over six months. The authors noted:

We found that the number of books in the home and the number of children that considered reading as a hobby had increased. Changes in the home from baseline to post-WLR also predicted larger improvements in executive functions, particularly for younger children and for families who reported lower family income.

The researchers also found that among traumatized and vulnerable children, especially those living in refugee camps, WLR is helping with anxiety, anger management and cultivates mental well-being. Given Dajani’s own background, she empathizes with the traumas of displacement, and WLR’s history has paralleled the 2013 influx into Jordan of refugees from Syria. By 2014, WLR had begun training ambassadors in Za’atari, one of the five major Syrian refugee camps in Jordan.

“Our WLR program often has the greatest impact in the harshest conditions,” explains Abudayyeh.

“A lot of NGOs provide people in refugee camps with the essential items needed to survive,” adds WLR field officer Laila Mushahwar. “WLR actually helps people thrive and believe in themselves.”

Research has found that especially among children who have experienced trauma, WLR’s activities cultivate mental well-being.

By 2016 WLR had ambassadors reading to children in all five refugee camps. That year it also began partnering with the UNHCR and Plan International to work in Ethiopia with refugees from South Sudan.

In March, when the COVID-19 pandemic forced families to shelter at home and schools to shut down, WLR began offering free trainings online in Arabic and English, posting read-aloud sessions on WLR’s YouTube channel and sharing stories from global ambassadors on Facebook and Twitter. WLR, Dajani explains, “becomes a placeholder to keep children engaged with learning in a fun way while schools are closed,” adding that the positive parent-child interactions it fosters are also beneficial.

“WLR is no longer just a program to foster a love of reading among children,” asserts Dajani. It has also grown into a global, internationally acclaimed movement that empowers WLR ambassadors to become community leaders.

“We have become a social movement, and we’ve gone viral,” she exclaims.

And for Dajani, it all goes back to the first command revealed to humanity in the Qur’an: “Iqra!” (“Read!”)

You may also be interested in...

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.

Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

Arts

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.

How Gulf's New Museums Are Championing Cultural Memory and Heritage

Arts

The result of decades of planning, new facilities in Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arabian Gulf reflect the region's cultural renaissance and effort to preserve its heritage.