The Liverpool Effect

Around the turn of the 20th century, an acrobat from Morocco named Achmed Ben Ibrahim settled near the thriving port of Liverpool, UK. Forgotten until the recent discovery of his 1906 tombstone, his story foreshadows the cultural impacts of the city’s most famous 21st-century resident—Egyptian soccer star Mohammed “Mo” Salah.

COURTESY ISMAEEL NAKHUDA

It was sometime in the mid-1980s, Ismaeel Nakhuda recalls, that the headstone with the Arabic inscription was found. Well-worn, it lay in a far corner of the Muslim section of the cemetery in Preston, England. Nakhuda’s late father, Mohammad, had that day been working with other volunteers to clear up the overgrown area.

The Arabic on the headstone translated, “Oh he who is deceased and whose mention will be forever.” Underneath that, it read in English, “Here repose the mortal remains of Achmed Ben Ibrahim of Maraksh, Morocco, who died January 24th, 1906, aged 60 years.” It was the oldest Muslim headstone in the cemetery.

“When my father saw the stone,” says Nakhuda, a Preston native and local journalist, “it really made him think about why the stone would be there, and who this man was. We were always attracted to the grave and wanted to find out who he was.”

Ben Ibrahim was buried on the margins of the yard, in what was then the section for paupers and nonconformists, apart from the sections for Anglicans and Catholics. The Muslim volunteers that day quickly noticed that his grave was not oriented toward Makkah.

The headstone, and Ben Ibrahim himself, remained something of a mystery, especially among local Muslims, who today number some 15,000 among the town’s 140,000 residents. But his life was often spoken about in the Nakhuda home, where Mohammad, who had come to England from India, would muse with Ismaeel about the life and journey of this “lone Arab chap,” Nakhuda says.

A few years ago, as a professional writer and amateur historian, Nakhuda decided to investigate. What he found reveals another chapter in the story of Islam in Victorian Britain, one that has an unexpected link to the present—through sport.

COURTESY ISMAEEL NAKHUDA

Ben Ibrahim, it turned out, was a professional acrobat.

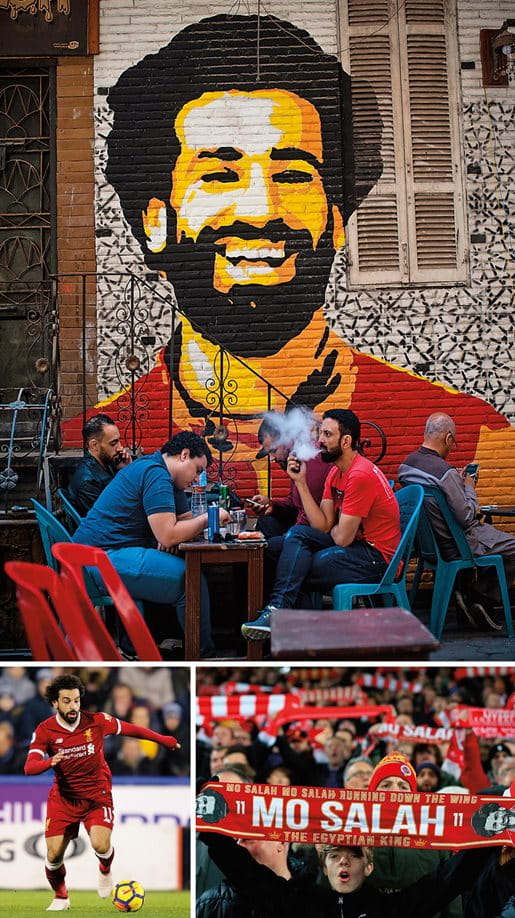

Today the Liverpool metropolitan area, where Preston lies nearby to the north end, stands as something of a pillar of diversity, a city recognized globally as one of the world’s friendliest and most eclectic urbanizations. It is also a city whose most famous current resident is a professional sportsman: Mohamed “Mo” Salah, superstar midfielder for both Liverpool Football Club in the English Premier League and the national squad of Salah’s native Egypt.

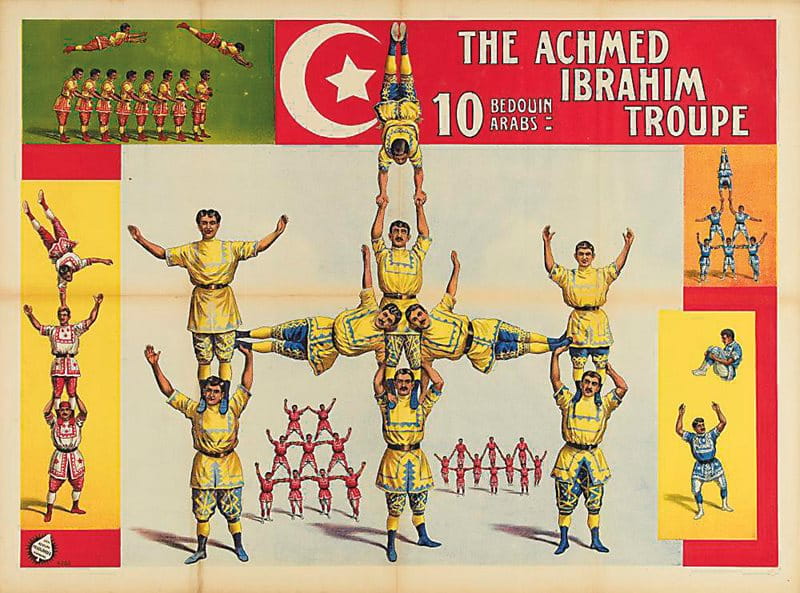

When Nakhuda began his research, he found no local records of Ben Ibrahim. But online, The British Newspaper Archive lit up his screen. Between 1895 and 1915, he found reviews, articles and advertisements about a group of traveling acrobats from Morocco, The Achmed Ibrahim Troupe.

He posted his findings on Twitter, and the Lancashire-based newspaper Asian Image used Nakhuda’s findings in a story on the history of early Muslim graves in the area.

Julie Knifton, a clerk at the Preston Cemetery, reached out to him with more about Ben Ibrahim’s burial. She confirmed that Ben Ibrahim was laid to rest in the outer section of the cemetery, in grave number 305 to be precise. More importantly, says Nakhuda, she explained that all the cemetery’s plots were dug in an east-west direction. “This probably explains why Achmed’s feet pointed west,” he says, instead of toward Makkah.

Records also showed the plot was bought for Ben Ibrahim by Charles Hutchinson, a Preston iron moulder, and his wife, Mary Ann Hutchinson. Later they themselves were buried in their own plots not in the Anglican section but near Ben Ibrahim. The Hutchinsons’s home address, 72 North Road, was also the address on Ben Ibrahim’s death certificate. How, Nakhuda wondered, would a tradesman such Hutchinson come to share a home with a foreign, and Muslim, acrobat? Were the Hutchinsons among Preston’s handful of English Muslims?

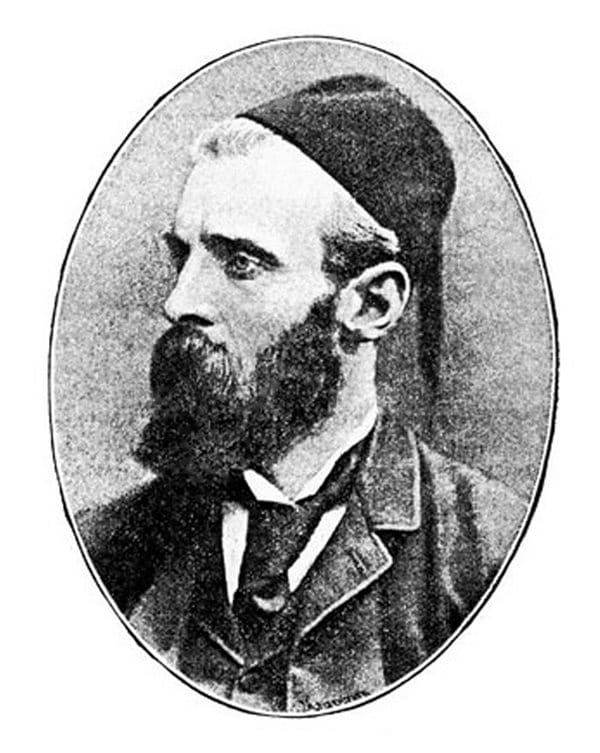

His search led to Abdullah Quilliam, leader of what was at the turn of the 20th century the rapidly growing, multinational Muslim community in Liverpool. It was an era when Liverpool was one of the most populous, most rapidly industrializing cities in Britain.

“To really understand Achmed Ben Ibrahim, you have to understand Quilliam’s community,” Nakhuda says. Today, he explains, many people in Liverpool think their star footballer Mo Salah is, as a celebrity who is Muslim, something new. “But there is a known Islamic background and influence in Liverpool going back a very long time, long before Mo Salah.”

Both before and after becoming a leader of Britain’s early Muslim community, Quilliam held “one of the most successful practices of law in the northwest of England,” noted Ron Geaves, a specialist in British Islamic history and author of Islam in Victorian Britain: The Life and Times of Abdullah Quilliam (Kube Publishing, 2009). It was after a trip to Morocco in 1887 that Quilliam became a Muslim and changed his given name, William Henry, to Abdullah, which means “servant of God.” That same year he founded the Liverpool Mosque and Muslim Institute, today under restoration by the Abdullah Quilliam Society. Throughout his lifetime, Liverpool was expanding to become Britain’s beating heart of transatlantic shipping and one of the busiest ports in the entire British commonwealth. The docks drew migrants from across the world, and Liverpool became England’s leading city for immigration.

Liverpool’s Muslim community comprised newcomers and visitors from across the globe, including countries in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, South Asia and others—enough that, with local converts, in 1896 the London Sunday Telegraph described Liverpool as “the center” of Islam “in the entirety of the British Isles.”

As a community they gathered for prayers on Fridays, celebrated holidays, took part in evening lectures and debates and joined picnics and the like. They also attended one another’s weddings and funerals. Unable to attend Ben Ibrahim’s funeral himself, Quilliam wrote of the acrobat and his graveside ceremony in Quilliam’s newspaper, The Crescent. He described Ben Ibrahim as a “sincere Muslim” who frequented the Liverpool mosque for prayers. He also noted that Ben Ibrahim was survived by “a wife, who embraced Islam”—a reference Nakhuda has, so far, been unable to attach to a name or other source. Quilliam also described Ben Ibrahim’s “active life” after “traveling in Europe for many years with a company of very clever Arab acrobats and tumblers”—The Achmed Ibrahim Troupe.

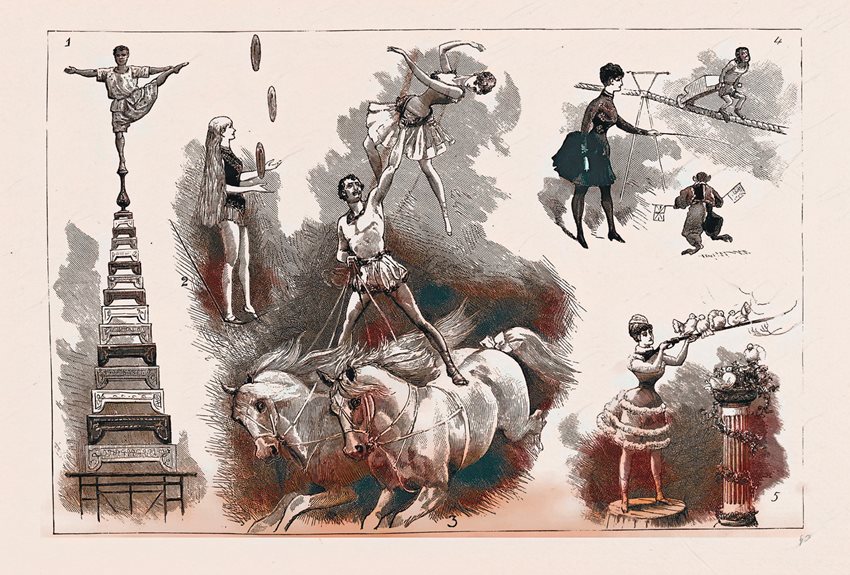

While not a competitive sport in an organized sense like soccer, acrobatic shows of Ben Ibrahim’s time were specialized circus acts that nonetheless competed for audiences and prestige. In addition to acrobats, they often included musicians, dancers, magicians, wrestlers and other various workers of wonders.

A great number of the acrobats came from Morocco. There were reasons for this, says Layachi El Habbouch, a professor at Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University in Morocco. He suggests that these acrobats did more than delight audiences: They helped transform Britain’s wider relationship with the world.

“We are used to thinking that the British were fascinated with the ‘cultural other,’ and they were,” says El Habbouch. “But the experience of Moroccan acrobat troupes tells another story—one of encounter and exchange.”

Touted as “Bedouin Arabs” or “Moroccan Arabs” in newspapers such as The Times, The Era and Bristol Mercury, Moroccan acrobats in particular were well-known for “human pyramids,” their use of rifles and swords on stage and, as El Habbouch describes, “a spectacle of bodies, myths and mechanical devices well-suited to the Oriental curiosity and industrial capacity of the Victorian Age.”

“These [human] pyramids were used to resist invasion. ... It was an anticolonial sport.”

—Layachi El Habbouch

While these played into many stereotypes of colonial ethnic exhibition, the performances also “created a whole new set of cross-cultural encounters that challenged British cultural discourse,” the professor continues.

The first-known Moroccan acrobat, he says, was Sidi Ahmad Ou Moussa, a 15th-century religious leader in the Lesser Atlas Mountains in the south of Morocco. His followers performed a mix of sport and art in preparation for both war and work. Their human pyramids, El Habbouch points out, were originally used to spot oncoming Portuguese warships.

“From the start these pyramids were used to resist invasion from foreign powers,” he says. “It was an anticolonial sport.”

Later, the acrobatics became a way to make a living in a world increasingly dominated by colonial powers. Moroccan acrobats—sometimes known colloquially as “the children of Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa”—performed for audiences in Spain, France, Italy, Germany and Britain.

As “spectacles of otherness,” their performances were received with great excitement. The Illustrated London News reported their “impossible feats” were “nightly received with shouts of surprised delight.”

El Habbouch says that many of the acrobats eventually found European and British communities in which to settle. As residents they went on to challenge stereotypes and begin a long process of redefining colonialist attitudes. It was the early effect of Muslims in Liverpool that continues today.

“Achmed stands as an example of how to live as a minority Muslim man in England,” says Nakhuda. And Liverpool, he maintains, “is a unique place in Britain. It has warm people. It’s a very welcoming city, and the football is the icing on the cake.” His own son, he adds, is a “diehard” Liverpool and Mo Salah fan. “But I don’t want to say there haven’t been difficulties.”

“For Mohamed Salah,” he says, “with his connections and the people he knows across the world, it literally tells you there is an Islamic legacy there.”

Idolized and beloved by fans across the globe, the 28-year-old “Egyptian King” has left his mark on Liverpool since joining the team in 2017. A 2019 study by Stanford University showed how Salah, as a celebrity footballer, has helped the relationship among Muslim communities and non-Muslim ones not only in Liverpool but also in Britain as a whole. The study dubbed it “The Mo Salah Effect.”

The researchers analyzed approximately 15 million tweets from UK football fans—8,600 in Liverpool proper—and found that among non-Muslims exposure to Salah sparked more inclusive responses to Muslims and even other UK minorities. It also contributed to a 19 percent drop in hate crimes and acts of bigotry in and around Liverpool, and a 53 percent decrease in anti-Muslim tweets among Liverpool fans. The effect isn’t limited to Salah, the study noted: Other celebrities “with role-model like qualities have long been thought to shape social attitudes.”

A 2019 study by Stanford University showed Salah has helped the relationship among Muslim and non-Muslim communities not only in Liverpool.

Salah’s role, while played out on a far larger stage Ben Ibrahim’s, extends also to the civic community of which he has been a part for four years. He has become a prominent philanthropist, working with partners such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and for the Vodafone Foundation he is its ambassador for Instant Network Schools, which connect refugee youth to digital education opportunities.

“Mohamed Salah shares our passion about the importance of education as a pivotal building block for personal and societal development,” says Andrew Dunnett, Vodafone’s group director of sustainable development goals and sustainable business and foundations.

But long before the Mo Salah Effect, there was Ben Ibrahim and The Achmed Ibrahim Troupe laying a foundation.

“What impact Achmed had on Preston, or its residents, is hard to say,” says Nakhuda. “For us second- and third-generation immigrants living in the UK, Achmed’s story helps us connect to our culture in the past and others who came before us, and others who came before them who have stories we don’t know about.”

Preston native, social worker and interfaith-relations activist Mohammed Ali sees figures like Ben Ibrahim and Salah as agents of a stronger civil society. “People just need more time to get to know one another,” he says.

“While we still recognize the importance of later migrant Muslim communities from South Asia, individuals like Achmed remind us of our deeper history in the UK,” Ali says, adding that he sees this among Preston’s journalists, shopkeepers, restaurant owners and others who play vital leadership roles in sustaining a healthy diverse community. “It’s not just famous Muslims, but everyday Muslims like me, my father, my daughter—or even Achmed Ben Ibrahim—that help embody the multiculturalism of the country.”

It is as if the effects of Ben Ibrahim and Salah are merely the most-visible tip of Liverpool’s human pyramid.

You may also be interested in...

See How Researcher Zainab Bahrani Rethinks Narrative of Ancient Art

History

Arts

Zainab Bahrani of Columbia University photographs ancient statues and reliefs carved into the rocks of remote Iraq to create a database for conservators and scholars. The effort is “decentering Europe from histories of art and histories of archaeology.”

Pearls, Power and Prestige: The Symbolism Behind Byzantine Jewelry

Arts

History

A 1,500-year-old gem-encrusted Byzantine bracelet reveals more than just its own history; it symbolizes an empire’s narrative.

Art Biennial Reviving the Ancient City of Bukhara, Uzbekistan

History

Culture

Uzbekistan’s inaugural biennial reactivates an ancient stop on the Silk Road through artworks jointly created by international and Uzbek artists.