Was Enheduanna the World’s First Author?

Four thousand years ago she was a princess and high priestess in the Sumerian city of Ur in modern-day Iraq. She was also a poet whose verses scribes wrote down in cuneiform on clay tablets and then did something new: They attributed the work to her by name—and now Enheduanna is more famous than ever.

Written by Lee Lawrence // Photographs Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum

I carried the basket of offerings. I sang the hymns of joy.

—from “The Exaltation of Inanna” ca. 2300-1800 BCE

The thought of a woman who lived more than 4,000 years ago in what is now Iraq being a topic of contemporary conversation thrills Gina Konstantopoulos, an assistant professor of Assyrian history at University of California Los Angeles. “She is not just ‘not forgotten,’” she says, “She has gained greater significance.”

Mesopotamia had many remarkable women, including some who wielded power, Konstantopoulos, 36, points out as she puts together a class assignment based on a clay tablet filled with rows of cuneiform characters. But she can name only one woman who has been repeatedly “chosen to be remembered and not overwritten”: Enheduanna.

Daughter of King Sargon of Akkad, Enheduanna was the high priestess in the Sumerian city of Ur, in the southern reaches of her father’s empire. Some 500 years after her death, her name appears as author of poems considered “central texts that are widely circulated.” And in recent years, Enheduanna has captured the attention of scholars and popular readers alike, expanding what Konstantopoulos calls her “many lives” and illuminating the importance of women in the world’s earliest civilization. “How quickly she acquired other lives, so to speak, and how notable they are,” Konstantopoulos says, fascinates her.

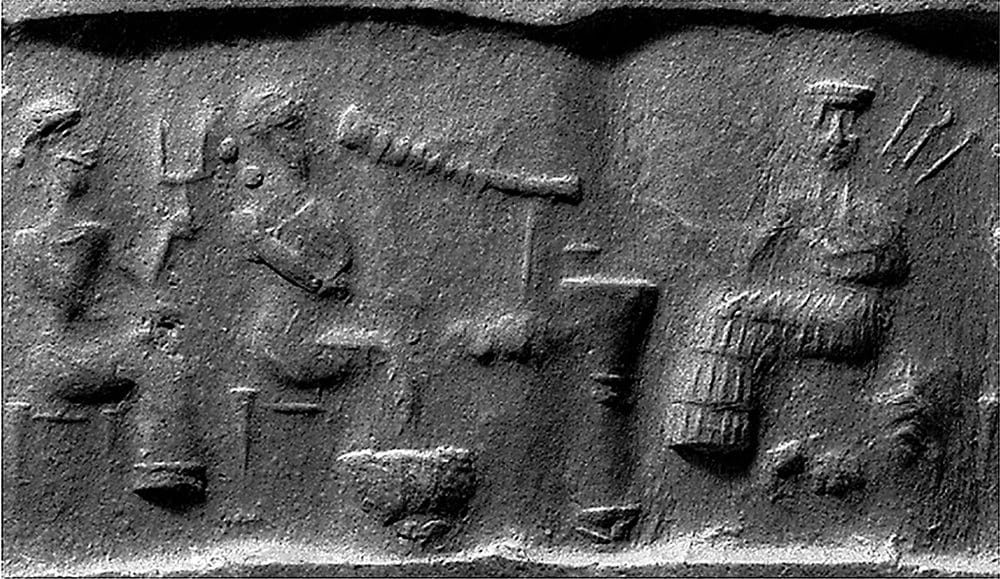

The first commemoration of Enheduanna had taken place around her own lifetime, in about 2300 BCE, in the city of Ur, when a sculptor chiseled into a thick disk of alabaster the relief of a woman presiding over a ritual offering. Depicted slightly larger than the other figures, she wears a tiered gown and a headdress with a rolled brim. On the back of the disk an inscription identifies her as en hedu-anna (high priestess-ornament of heaven) in Sumerian. As priestess, Enheduanna served Nanna, the city’s principal god and father of Inanna, the goddess of love and war.

Some 500 years later, during the period known as Old Babylonian, scribes remembered Enheduanna as they copied and disseminated tablets with Sumerian poems that name her as the narrator and, in some cases, as author. A compilation inscribed on clay tablets known today as the Temple Hymns, for example, attributes the high priestess as its composer. According to a translation by the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, the closing lines read, “The compiler of the tablets was En-hedu-ana. / My king, something has been created that no one has created before.”

Another set of lines, from another hymn attributed to Enheduanna, “The Exaltation of Inanna,” sheds light on some of the duties of the high priestess as intercessor, mediator and eulogist. “Let me, Enheduanna, recite a prayer to her / Let me give free vent to my tears like sweet drink for the holy Inanna!”

In the same hymn, Enheduanna also describes how a rebellious lord expelled her from her temple: “Like a swallow he made me fly from the window … / He stripped me of the crown appropriate for the high priesthood.” Then, having received no help from Nanna: “As for me, my Nanna takes no heed of me. // … may your heart take pity on me!”

A woman who lived more than 4,000 years ago in today’s Iraq “is not just ‘not forgotten.’ ... She has gained greater significance.”

Gina Konstantopoulos, Assyriologist, UCLA

“The Exaltation,” as it is often called, was the first text related to Enheduanna to be published in translation, first in 1958 in a German journal and, 10 years later, in English. Its English translators, Assyriologists William W. Hallo and J. J. A. van Dijk, wrote that they had identified “a corpus of poetry of the very first rank which not only reveals the author’s name, but delineates that author for us in truly autobiographical fashion.” They argue that this set of poetry includes the “Temple Hymns” as well as “The Hymn to Inanna,” whose narrator is Enheduanna, and “Inanna and Ebih,” in which the goddess reduces a mountain—Mount Ebih—to charred rubble for refusing to bow. This last one contains no mention of Enheduanna, but the translators deemed it was written in the same style as the others, with Inanna regarded as supreme over other gods. Mesopotamia, they announced, had produced history’s first named author.

Scholars, however, are not in full agreement. Some, like Sidney Babcock, head of the department of ancient seals and tablets at The Morgan Library & Museum, in New York, point to the ”signatures” in the text and the imprimatur of the Old Babylonian scribes as sufficient evidence of authorship. Others, like Eleanor Robson, who has written extensively about cuneiform culture, argue that stylistically the Sumerian is too late for Enheduanna herself and that the scribes could have had more than a copyist’s hand in it, perhaps inserting Enheduanna’s name to build cultural identity and pride around a respected figure from the past.

This debate notwithstanding, interest in Enheduanna is now flourishing in both academic and popular spheres. Take for example Sophus Helle, 28, a postdoctoral fellow at Freie Universität Berlin and Oxford University working on a book about her. At the mention of Enheduanna, he lights up. Whether the verses date to 2300 BCE or 1800 BCE, he says, “these poems stand out.”

In his translation we see Enheduanna’s inner turmoil, “I went to the light, but the light burned me; / I went to the shadow, but it was shrouded in storms. … But still my case stays open, and an evil verdict coils around me—is it mine?” This hymn also exudes much fierceness, as shown in the lines, “Let them know that you grind skulls to dust. / Let them know that you eat corpses like a lion.” And in the “Hymn to Inanna,” Helle singles out some bowl-me-over imagery: “Their shouts weigh on wasteland and meadow. / Her cry is a storm: skins crawl throughout the lands.”

Helle says his translations are “intentionally very free” to better convey both the original’s meaning and its poetic sensibility. He hopes his analysis also helps readers appreciate, for example, Sumerian puns, as well as the complexity, ambiguity and subtlety of an ancient language scholars are still unraveling.

“I believe she was not the first one. We have to think there were hundreds of women before her participating in oral literature.”

Haider Almamori, archeologist, University of Babylon

In Enheduanna’s modern homeland, archeologist Haider Almamori, 50, is equally keen on helping fellow Iraqis appreciate Sumerian literature and “the great woman,” as he refers to Enheduanna. For some 18 years, he worked at Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, excavating sites, heading archeological digs and eventually directing the institution. For the last five years he has been teaching upper-level classes at the University of Babylon in central Iraq. “Most people talk about Inanna and Ishtar”—the latter is the former’s name in the language of Babylon—“but not Enheduanna, almost no one,” he says, shaking his head. While his students read Sumerian, he adds, they have been exposed almost exclusively to tablets about “grains, seeds, barley, leather.” For two years he has been working on introducing a course on literature, and in it he hopes to talk about more than just Enheduanna.

“I believe she was not the first one,” he says. “We have to think there were hundreds of women before her participating in oral literature.”

Even for Enheduanna, a high priestess and the daughter of a king, archeological evidence remains scarce. “The alabaster disk and a few seals are really it,” says Babcock, 71, who is cocurating The Morgan Library & Museum exhibit She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, scheduled to open in October. The exhibit will display the disk and cylinder seals—including some attesting that Enheduanna had a scribe and a hairdresser—along with other artifacts such as statues, tablets, ornaments and reliefs that relate to the roles of priestesses and other prominent women. In all, Babcock negotiated loans of some 90 objects from museums and collections in North America, Europe and Israel.

In the fall of 2019, he introduced the objects to young scholars through a class at Columbia University. By the end of the semester, he had invited doctoral candidate Erhan Tamur, 33, to cocurate the exhibit, and he had asked other students to adapt their term papers into essays to publish in its catalog.

One of the students, Majdolene Dajani, 25, compares depictions of Inanna on cylinder seals to descriptions of the goddess—winged and having a “terrible glance”—found in “The Exaltation.” Dajani finds that “text and image remind you of each other,” though she is quick to add there is no way to know whether a particular artist was inspired by the Enheduanna-related texts.

Still, she finds enough rapport between the media to lay the groundwork for future research, according to Babcock, who has long thought Enheduanna’s writings might have been a reason portrayals of deities became much more numerous after King Sargon came to power.

Enheduanna “wrote about herself, how she got kicked out of power, and it was really bad ... but then she came back.”

Meagan Blyth, Canberra University

Meanwhile, fellow student Kutay Şen, 30, detects another remarkable link between art and writing, this time in the statue of a seated female. He draws attention to the tablet resting on her lap: It is scored with parallel lines, which was a standard way of organizing cuneiform characters, but here, he points out, there are no characters. The tablet is blank.

His research leads him to believe that the statue was made 200 to 300 years after Enheduanna and that it represents a high priestess offering a deity “the idea—and the intention—of writing,” he says. It attests, he adds, “to writing being of significance, and worth dedicating to a god, and its association with women.”

Scholars are not the only ones engaging with early writing. Konstantopoulos points to contemporary poets who have picked up on Enheduanna’s lament that Nanna did not come to her aid when she was exiled from the temple, citing Iraqi poet Amal Al-Jubouri’s 1999 “Enheduanna and Goethe.” Al-Jubouri’s lines “while you drag me to your ‘West-East Divan’ / … O East, what have you done to me? / I loved you but you brought me shame,” Konstantopoulos says, reverberate with “the idea of being abandoned that Enheduanna feels in her own text.”

In Australia, Meagan Blyth, 27, devoted a year and a half to reinterpreting “The Exaltation” as a historical novella for her 2019 honors undergraduate thesis at Canberra University. She calls attention to the poem’s vivid descriptions, ranges of emotions and archetypal figures, all of which she feels enhance its sense of immediacy and relevance. “This wasn’t just some person who existed 4,000 years ago whose life is so vastly different from mine that I couldn’t possibly fathom anything about her,” says Blyth. Enheduanna “wrote about herself, how she got kicked out of power, and it was really bad, and she didn’t like it, but then she came back. And that,” she says, “happens in history all the time.”

For Polina Zioga, director of the Interactive Filmmaking Lab at the University of Stirling in Scotland, it was the violent images and urban references in the verses that attracted her. Zioga first read “The Exaltation” in Greek in 2013, and its rage-filled imagery resonated, she says, “because most of us do go through crises, do go through acute emotional states.”

But the poem is not, she adds, “a self-pitying text,” nor is it merely vengeful; rather, “it’s the need for justice to prevail.” The text shifts, she says, from a personal to a societal perspective. At the time, the 2008 financial crisis that rocked the globe, and that hit Greece especially hard, still simmered in her memory. It was this “sense of responsibility—toward the city in ancient times and toward democracy in present times—that is very relevant.”

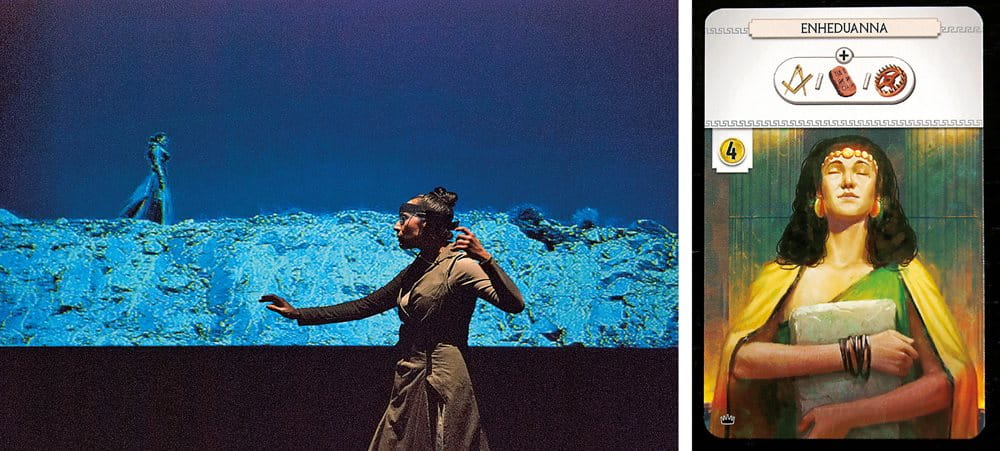

In producing Enheduanna: A Manifesto of Falling, which premiered in 2015, Zioga intercut verses from “The Exaltation” with words by Maya Angelou, Virginia Woolf, Theodore Adorno, Pavlina Pamboudi, Marguerite Yourcenar and other writers. The 50-minute mixed-media event broke technological ground in theater: As video projections filled a screen, the show’s solo performer and audience members all wore electroencephalographic headsets that intermittently picked up brain activity and colored the stage in real time accordingly to the results. Scenes that evoked relaxed but awake alpha waves tinged the stage with greens; more cognitive gamma waves produced reds; meditative but also emotionally stressed theta waves brought on blues. It was the premiere of a live, brain-computer interface performance, and in it the world’s first author seemed right at home. “The Exaltation,” says Zioga, “is one of these works that is safe to describe as universal and timeless, and therefore contemporary.”

“‘The Exaltation’ is one of these works that is safe to describe as universal and timeless, and therefore contemporary.”

Polina Zioga, director, University of Stirling

Others, too, are showing that one doesn’t need to read cuneiform to appreciate and interpret the verse of Enheduanna. After Jungian analyst Betty De Shong Meador published interpretive translations and analyses in 2001 and 2008, word of the high priestess spread further. In 2016, for example, teenage readers of Kate Schatz’s Rad Women Worldwide met Enheduanna as the oldest among the “bold, brave women who lived awesome, exciting, revolutionary, historic, and world-changing lives.” Two years later, in What Would Boudicca Do? Everyday Problems Solved by History’s Most Remarkable Women, E. Foley described the high priestess as a role model for letting one’s creativity flow. And online, feminist blogs invoke her, and gamers might meet her in the 7 Wonders board game and in Civilization 6—the list goes on.

None of this surprises Konstantopoulos. “We’re very fond of firsts,” she says. “So, when we have this named female figure who is—either actually or constructed to be—the first named author, that’s a very compelling image.” But beyond that, she wants everyone to know that as remarkable as Enheduanna is, “the contributions of women in Mesopotamia, and the contributions of women in ancient history, as a whole, is also, in its own right, extraordinary.”

You may also be interested in...

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Pearls, Power and Prestige: The Symbolism Behind Byzantine Jewelry

Arts

History

A 1,500-year-old gem-encrusted Byzantine bracelet reveals more than just its own history; it symbolizes an empire’s narrative.

How Ancient Knowledge Shaped Modern Technology

History

Science & Nature

Part 3 of our series celebrating AramcoWorld’s 75th anniversary highlights the magazine’s emphasis on experts and institutions that push the boundaries of present-day knowledge while paying homage to historical figures and writings that paved their way.