Explore Underwater Photography With Diver Eric Hanauer

12 min

Written by Waleed Dashash

Photographed by Eric Hanauer

The Brothers Islands lie in the Red Sea, about an even-hour fisherman’s boat ride offshore from mainland Egypt. Eric Hanauer made the trip to write about and photograph the islands’ most prominent feature for his first AramcoWorld story, titled “The Lighthouse of The Brothers,” which was published in the September/October 1984 issue. Five years later, Hanauer’s familiarity with the Red Sea landed him another assignment with AramcoWorld, only this time he needed different equipment. “Egypt’s Underwater World” required the scuba gear, wetsuit and camera that he’d been using to engage readers of a prominent diving magazine. The story’s publication in the May/June 1989 issue of AramcoWorld exposed the underwater photojournalist’s work to an entirely new audience.

From his home in California, Hanauer reflected on the early days of his four-plus-decade career as an underwater photographer and writer.

What came first: diver, photographer, writer or journalist?

I started shooting pictures when I was a preteen. I had an old point-and-shoot camera and started shooting then. Then I started diving in 1959, became an instructor, and since I was shooting pictures on land, the natural thing was to shoot underwater. In those days the reason people were diving was to kill things, to shoot fish, catch lobsters, and eventually environmental consciousness took over. Actually, it takes a lot more skill to shoot a good picture of a marine animal than to kill it because you could kill it from 2 meters away, and to get a good photograph you have to be pretty close.

It was a greater challenge to come back with good photographs, especially in the film days when you had only 36 images and you couldn’t see what you shot until after you got home. It was a greater challenge than shooting fish.

Definitely, I was a writer first. At that time in the diving community, you had to do both [writing and photography]. I was fortunate to have very hard English teachers in elementary school and high school. I didn’t appreciate them at the time, but they made me a writer. Writing has always come easily to me, and the way to get photographs published was to write. My first article was in 1977 in Skin Diving magazine. That was the biggest magazine in the world devoted to diving at the time; it stopped publication after 50 years in 2002, and I wrote for them for 25 years. … [Writing is] a creative process where I really enjoy the end result just like I enjoy the result of shooting a good photograph, and now with digital I can edit that photograph, bring out everything that I wanted to convey in the first place.

What was the importance of the story about the Red Sea back in the ’90s, and how can we relate to it today?

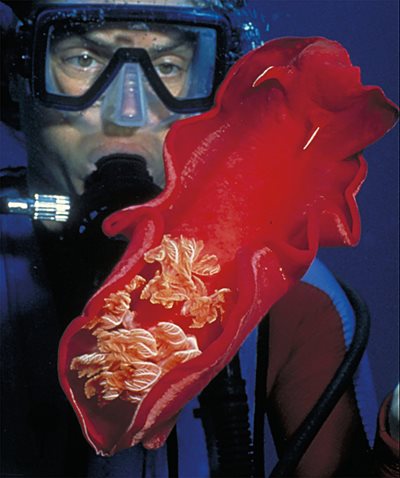

It’s tremendously rich in its marine life and in color. In a lot of areas, like the Caribbean, the colors are pastels; in the Red Sea, there are brilliant primary colors, reds, greens and yellows. There’s clouds of fish, tiny orange fish called anthias, maybe 2 inches long, and clouds of hundreds of them around the reefs, tremendously rich marine life. Clear water and the contrast between the brilliant colors of underwater and the desert above is just breathtaking. Plus, we’re looking at over 5,000 years of history.

At the time [the AramcoWorld story] opened people’s eyes. The audience that I was writing to was very different than the audience I usually write for. My experience, probably 90-95% of my writing has been in diving magazines, and I have written to divers. … So [the story] opened my writing to a broader audience. And opened the underwater world of the Red Sea to people who may not been aware of it.

Left to right The hawksbill turtle is common in the Red Sea; a starfish clings to its perch; and anemonefish, also known as clownfish, are immune to the anemone’s sting.

How did you prepare for these stories?

I kept very detailed journals, and at that time before computers, they were written out longhand. I wrote journals every day. I kept extensive dive logs; as soon as I got out of the water, I’d write down what I saw, what I experienced. So I had a lot of notes to work from. And I did my homework. I did a lot of reading, interviewed a lot of people [divers and dive guides]. At the time, for example, the southern part of the Egyptian Red Sea was terra incognita for the most part. And I interviewed people like Adel Taher, who had been there and had dived those places.

Underwater photography was fairly new back then. How experienced were you with it?

I started underwater photography in the mid-1970s. By the time I got to Egypt, equipment had improved considerably and it has continued to improve, of course, with digital. For example, at that time we were shooting film, [and] we had 36 pictures on a roll of film. Now we have unlimited pictures. We were making a dive at The Brothers one time, and at Little Brother island I shot my 36 pictures pretty quickly, swam back to the boat, and underneath the boat was a gigantic oceanic whitetip shark, just about as big as the boat, just hanging out there with a group of pilot fish in front of him. And I was out of film. So all I could do is wave at it and say, “Hello, this would’ve been a great photograph, maybe next time.” There was never a next time.