A British Historian's Journey into Arabia's Past

Historian William Facey rescues French Alsatian geographer Charles Huber from semiobscurity and places him in the pantheon of great Arabian explorers.

The Arabian Peninsula sparked the interest of historian, museum planner and writer William Facey about 50 years ago, in 1974. Fresh out of Wadham College, Oxford, where he read classics, philosophy and art history, and after teaching for a year in Athens, he answered an ad for a research position to help design the National Museum of Qatar. Inspired by Oxford, England’s Ashmolean Museum, with its extensive Greek, Egyptian and Roman antiquities collection, Facey was intent on finding a place in the world of museums, but he never envisioned focusing on the Arabian Peninsula. However, he soon found himself gravitating toward the region’s history and culture.

Over the following decades, Facey helped develop archeology, ethnography and natural history exhibitions and museums, working to crystallize museum concepts, develop displays and research exhibit topics. His work in Qatar attracted the attention of Saudi Arabia’s Department of Antiquities and Museums. From the 1970s onward, Facey worked primarily in Saudi Arabia as the country went through a boom of museum building and expansion.

On the lookout for Arabian history materials, in the late 1970s, while browsing a book catalog, Facey came across a copy of the first volume of Tagbuch einer Reise in Inner-Arabien, 1883–84, the diary of the eminent German orientalist and explorer Julius Euting’s Arabian journey. Facey was enchanted by the work, especially Euting’s vivid sketches. Two decades later, having gone into publishing, Facey decided to issue a new edition of Euting’s diaries and sketchbooks.

While writing the introduction and editing the English translation, Facey found himself wanting to better understand Euting’s partner, Charles Huber, a French explorer who had completed an Arabian journey two years earlier, with whom Euting repeatedly clashed during their trip.

Huber, a self-taught geographer, pioneered scientific mapping of inland Arabia, was one of the first to document north Arabian inscriptions and rock art, and is credited at the Louvre with discovering the fifth-century-BCE Aramaic-inscribed Tayma Stele before his death in 1884 at 36 years old. Despite these accomplishments, Facey struggled to even find obituaries for Huber, who was murdered on the Red Sea coast shortly after he and Euting parted ways.

In 2020 Facey decided to produce a volume that would include the first Huber biography, the first English translation of Huber’s journal, published posthumously in the Bulletin de la Société de Géographie in 1884 and 1885, related correspondence, plus photographs and a fold-out reproduction of the map of his journey.

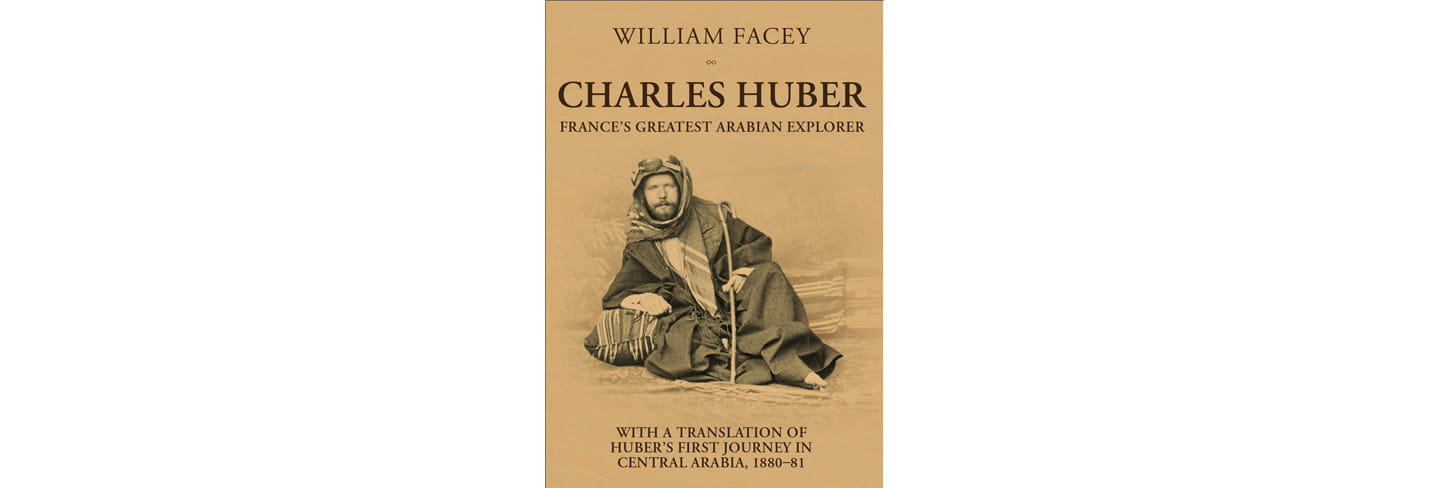

Facey recently spoke with AramcoWorld about writing Charles Huber: France’s Greatest Arabian Explorer, the first consideration of Huber’s remarkable life and work.

Charles Huber: France’s Greatest Arabian Explorer · William Facey. · Arabian Publishing, 2022.

How did you go from working on Euting’s journal (Julius Euting: Diary of a Journey Through Inner Arabia, 1883–1884, slated for 2024) to translating Huber’s journal and related correspondence and writing Huber’s biography?

One thing that bothered me about the Euting project was that I knew so little about Huber’s journeys. I had the Bulletin of the Société de Géographie diary excerpts about his first Arabian journey, published [posthumously] in 1884 to 1885, but you never see these turning up in bibliographies. In the first [pandemic] lockdown, I thought since I’ve got all this time, I might as well translate them.

I wasn’t thinking about a book—I did it for my own research purposes. But these things grow, don’t they? You get started on something, and it turns into something bigger. During the pandemic, I was wondering how I was going to spend my time, so I started working on the Huber book.

With so little written about Huber, how did you go about researching his life?

Some details were available in an Alsace biographical dictionary. The rest emerged in snippets embedded in archives in France. I was nervous that the French might be reluctant to assist me because of my conclusion Huber did not discover the Tayma Stele, but the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres could not have been more helpful.

What did you learn about Huber that most surprised you?

You would think Huber would be in the mold of a European explorer: well-educated and very prepared. But he wasn’t. He was a working-class kid and basically self-educated. He had a gift for languages. By the time he had been in Arabia a few weeks, he was very good at the local vernacular. Huber was very thorough, very obsessive, very compulsive and determined to get his own way.

What was the source of the conflict between Huber and Euting?

There was Euting, the German, and Huber, the Frenchman. It was never going to work. The 1871 loss of Alsace to Germany was a massive humiliation for France. It puzzles me now, in that context, why a Frenchman from Alsace and a German would ever have contemplated going on an expedition together. That was the fatal difference between them, but there were others: Euting was Protestant, an upper-middle-class academic, while Huber was Catholic and a rather dodgy working-class kid.

Why are both Huber and Euting important today?

Nobody before them had done any archeological investigations [in Saudi Arabia] in the sense that we understand it today. For example, Georg Wallin, the Finnish explorer who made his trans-Arabian journeys in the 1840s, went through Tayma. There are these great towering ruins everywhere, city walls and ruin fields inside, but Wallin said nothing about it. Huber and Euting, on the other hand, were really interested, and this is really the foundation of Saudi Arabian archeology. This is where it begins.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

You may also be interested in...

Nakshi Kantha Embroidery: Tales of Heritage and Revival

Arts

History

A traditional form of quilting in Bangladesh in which women embroider family history, love and memory into the fabric is blanketing markets locally and beyond.

Pearls, Power and Prestige: The Symbolism Behind Byzantine Jewelry

Arts

History

A 1,500-year-old gem-encrusted Byzantine bracelet reveals more than just its own history; it symbolizes an empire’s narrative.

AramcoWorld: Celebrating 75 Years of Global Historical Insight

History

Cover stories that bridge the past and present offer insights into humanity’s common ground. From archeology to historical objects, people, places and more we share connections to one another.