Preserving Senegal’s Pirogues: Analyzing and Solving Problems

Environmental Studies

Anthropology

West Africa

Explore how forces of modernity threaten the small-scale fishing that is central to life in Senegal.

The following activities and abridged text build off “Going Pirogue, the Boats Feeding a Nation,” written by Tristan Rutherford and photographed by Samantha Reinders.

WARM UP

Scan the article’s photos and captions to predict its theme and main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Examine words that describe artisanal fishing, then find examples from the article and write your own description.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Analyze and discuss the problems facing Senegal’s artisanal fishing industry and the possible solutions for saving it. Determine what actions individuals and countries could take to protect the pirogue culture and to help industry thrive in Senegal.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Explore how to analyze visual images to formulate an impression, then test that impression by reading the captions for further information.

Going Pirogue, the Boats Feeding a Nation

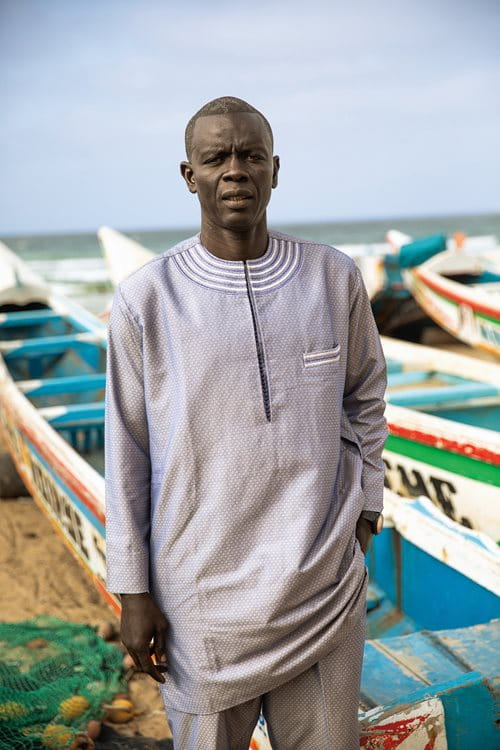

On the white sands of Senegal’s Ouakam beaches, rows of narrow, canoe-like pirogues line up. Every morning, Senegalese fishermen, as they have done for hundreds of years, prepare to launch the boats into the Atlantic. They will spend hours or days at a time at sea, catching giant trevally and marlin.

Here, at Soumbédioune’s horseshoe bay, is the region’s main pirogue construction site, called a chantier. Boatbuilders work in an area filled with loose and half-constructed wood, taking only short breaks to rest under nearby mango trees or have a quick tea or coffee.

For more than a decade, Mor Diouf has worked among them, crafting pirogues. Currently he is building a 6-meter pirogue with a 6-person capacity. This is considered a small to midsized vessel. It will take about four days to complete, and will sell for CAF 900,000, or US$1,500.

Once it’s finished, the pirogue will be launched without celebration. It takes to the sea with only one expectation: that it will be useful for catching fish. That’s what makes a pirogue valuable.

Question: What evidence shows that fishing is very important in Senegal?

The name Senegal refers to the fishing boats; and fishing provides 75 percent of the animal protein eaten by Senegal’s population.

Fishing is serious business in Senegal, Diouf says. It is so serious that even the country’s name reflects fishing and boating culture. It comes from Sunu gaal, which in the national Wolof language means “our pirogue.”

Along Senegal’s coast, small-scale fishing provides up to 75 percent of the animal protein eaten by its 17 million residents. Senegal’s fishing industry employs just over a half a million people. They are fishermen, fishmongers and shipwrights. Together, they provide food for the people.

This chantier produces, repairs, and retires pirogues. Some 20,000 pirogues have been crafted here, just a 20-minute drive south from Ouakam.

Diouf is known for making excellent pirogues, which are defined by their speed and sturdiness. He recently finished a 20-meter pirogue, designed to be at sea for a week at a time. It took 15 days to build and a crew of 10 to heave it into the water.

Diouf says the larger pirogues are built for long trips. They carry one or two mounted outboard engines and have space to store provisions for a crew to stay out at sea for a week or more at a time.

While the fishermen are at sea, however, there is no singing, storytelling or listening to music on one’s smartphone. It’s all business. It’s “just catching fish,” says Diouf.

Question: Why are pirogues made from two different types of wood?

One is soft and pliable for shaping the pirogue; the other is hard and durable for lasting a long time in saltwater.

Pirogues are made from two types of wood. Samba wood, from Cote d’Ivoire, is light and flexible, famous for its use in crafting pirogues. Pirogue hulls, however, are made from the more durable West African redwood from Casamance, Senegal’s tropical southern region. Redwood can withstand saltwater conditions for about a decade before needing to be replaced.

Question: Why did Senegalese fishermen refuse to use the fiberglass boats?

Because they were not locally made in the traditional way

Earlier this year, foreign fishing enterprises who fish in Senegalese waters, made a good-will gesture. A French company and a Japanese government agency gave 38 fiberglass fishing canoes to Senegal. The boats are thought to be unsinkable and longer lasting than locally made pirogues. But they’re not made in the local tradition. So, no one would use them.

“We wouldn’t get on a fiberglass boat,” Diouf says emphatically, almost offended by the thought. “Don’t even talk to me about it.”

Each boat built at the chantier is painted with bright colors and decorated elaborately. But why? After all, the boats are fishing far from shore, and are rarely seen after launch.

“People want to decorate them because everybody wants their own unique design,” says pirogue painter Demba Gaye.

Local elders, like retired fisher Ousmane, know how important the pirogue boats are. They are central to fishing and feeding the people of Senegal. They also connect people to their ancestors.

“Our grandfathers and fathers were all fishers,” says Ousmane.

In addition to providing food, fishing is also used to teach life lessons, Ousmane says. If a male student is failing at school, for example, someone takes him fishing. It’s also good exercise for the mind and body to catch large fish, he says. But one has to learn how to catch large fish.

Question: What factors are challenging traditional fishermen?

Big boats are overfishing, and local divers are also taking fish that traditional fishermen might otherwise catch.

Yet big fish like fighting marlins are becoming harder to get. Foreign boats and fishermen are crowding the Senegal coast. They’re taking more fish than can be replenished during a natural cycle.

Assane, a longtime fisherman, says that these outsiders come at night. “If people just took a small amount, giving fish time to reproduce, it would be OK. But with big boats from China or Russia, they take all of them.”

To make matters worse, Senegalese divers now come at night, too, and spearfish large fish while the pirogue fishermen are asleep. “They dive with a (waterproof) torch so strong that it’s like daylight underwater,” Ousmane says.

As a result, many of the local Senegalese fishermen are coming home on their pirogues empty-handed. Some of the older retirees fear that it may become impossible to make a living on the pirogues.

To adapt, pirogues are now being used in different ways. For $2 a ride, the boats serve as tourist shuttles, weaving through the waves to Ngor Island across the bay. In other areas of Senegal, pirogues have been adapted to become riverine passenger and fishing crafts, as well, made with flatter hulls and smaller sails. They also continue to evolve in size to be able to accept larger cargo.

But the pirogue community has not given up on its tradition, or future, and many in the boating community are talking about how to preserve pirogue fishing in Ouakam. Doing so is necessary, since 80 percent of the catch in Senegal comes from small-scale fishers, and landlocked West African countries, such as Mali and Burkina Faso, also rely on the fish from Senegal ports.

In these challenging times, members of Senegal’s coastal communities look out for each other. If fishermen come back with no fish, they can take two or three fish from another fisherman to have something to eat.

It seems many are determined to keep the pirogues, and all they represent to Senegal, intact for generations to come. With millions depending on them, more must be done to preserve the fish supply and maintain the tradition of pirogue fishing.

“The base of our food is fish,” says Gueye. “This is why pirogues are extremely important in the lives of Senegalese.”

Other lessons

Aramco World Learning Center: No Passport Required

For the Teacher's Desk

Project-based learning lies at the heart of AramcoWorld’s Learning Center. Link its resources into classroom curriculum, no matter the subject.

How Art Connects

For the Teacher's Desk

Art links everything—cultures, history, even math. Want to hook students? Try teaching through the art that surrounds us with these stories.

Teaching Empathy: Five Classroom Activities From AramcoWorld

For the Teacher's Desk

Help students build empathy and community for the academic year with AramcoWorld’s stories and Learning Center lessons.