The Resilient Fig Tree: Analyzing Strategies for Thriving in a Warming World

Environmental Studies

History

North Africa

Levant

The following activities and abridge text built off "Can Fig Trees Help Us Adapt to a Changing Climate?", written and photographed by Rebecca Marshall.

WARM UP

Scan the article’s photos and captions to predict its theme and main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Write a short paragraph on the historical significance of fig trees and their resilience to climate change.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Analyze the goals of the FIGGEN project as it relates to the past, present and future of fig trees.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Analyze a video minidocumentary on the work of FIGGEN.

Abdessalem Zgaya stands on baked, cracking soil where water once trickled, looking over his fruit fields near Kesra, northern Tunisia. It’s the first time he has seen a spring dry up. “The summers just get hotter and hotter,” he says, adjusting his cap to block the sun. “I don’t know how much longer my lemon trees can survive.”

Amid the still, heavy air, Zgaya points out a row of young trees, starkly green against the brown-gold tones of the landscape. “The figs are different. See how their leaves are wilting? It helps the plants conserve water in the heat. When it gets cooler tonight, they’ll perk back up.”

Indeed, fig trees tolerate drought better than most, and as agriculture struggles in a warming world, that makes them ripe for study. For nearly four years, a Mediterranean research initiative, FIGGEN, has assessed how figs succeed while other crops fail. Fig farmers stand to benefit from FIGGEN’s findings.

The study, which concludes in 2024, involves DNA stress testing and analysis of figs in Tunisia, Turkey and Spain. Scientists have been working to identify specific genetic traits that enable figs to cope with hot and dry conditions. When FIGGEN publishes the results, Mediterranean farmers may choose to grow the most promising types. Additionally, the study aims to plant a seed for preserving the biodiversity of increasingly arid ecosystems.

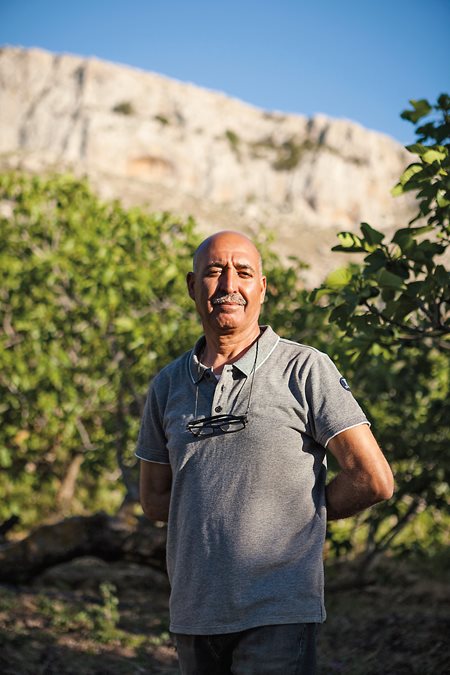

![“[Figs] were here long before us, and knowledge we have of how to take care of them is part of our heritage,” says farmer Abdessalem Zgaya.](https://www.aramcoworld.com/-/media/aramco-world/lessons/2024/figs-banner-images/image-2.jpg)

How did figs survive throughout history?

Back in 2006, in the prehistoric ruins in the Jordan River Valley, a team of archeobotanists found proof that figs had been cultivated 11,400 years ago—long before the domestication of wheat, barley or legumes. As they outlined in the journal Science, this discovery could make the fruit trees the oldest-known agricultural crop.

Question: What are some examples of the fig’s place in history?

Religious symbolism in the Bible and Qur'an. Having a role in the birth of civilization. Cultivated since ancient times. Very popular during the Greek and Roman civilizations.

The fig’s place in our history and culture is indeed deeply rooted. From its culinary use to its religious symbolism in both the Bible and the Qur’an, the fig has played a role in the birth of civilization. Believed to be indigenous to northern Asia Minor, figs have been cultivated since ancient times. During the Greek and Roman empires, the popularity of figs spread, and their ability to thrive in semiarid climates made them an important crop across the Mediterranean Basin by the first century CE.

Nowadays, agricultural conditions in the region are changing. Land temperatures have increased by 2 degrees Celsius since the Industrial Era. This is twice the global average and the future promises more summer heatwaves and less rain. Such conditions also raise salt levels in dwindling groundwater, compounding the challenges that plants face.

Question: What are some examples of the resiliency of figs to harsh conditions?

Figs survive with minimal water and have little need for fertilizer. Resistant to pests. The grow back after forest fires. They can grow on cliffs or in walls.

Fig trees, however, survive with minimal water, have little need for fertilizer and are resistant to many pests. They may burn in a forest fire but will grow back the following year. When a fig tree is cut down, a new shoot will generally spring from its stump. Wild figs may even grow on cliffs or in walls with no soil or water. Their formidable, fast-growing roots can tear rocks apart, finding water where other trees simply cannot.

That makes many of the 800 species of the Ficus genus (scientific name for fig trees) ecologically exceptional. Shade offered by their dense leaf canopies cools hot air and slows evaporation and the flow of rainwater over the ground. This limits erosion and retains soil moisture and organic matter. Ficus fruits are a food source for many animals. Animals disperse their seeds increasing the landscapes biodiversity.

The FIGGEN project

A few years ago, Riccardo Gucci, a professor of agrarian science at the University of Pisa in Italy, saw a fig tree growing robustly out of a cliff. He was curious how any plant could thrive in such an environment. This led to the development of FIGGEN.

To discover which varieties of Ficus carica (the common fig) cope best with climate change, FIGGEN teams gathered cuttings from 270 different varieties. Some fig trees produce fruit once a year and others two or three times. Some have male and female flowers, others only female. Some trees need pollination, whereas others can produce fruit without it. In laboratory gardens, eight plants of each variety were grown in pots, and in late 2021 the testing of their resilience to a lack of water and increased salinity began.

Question: What do the researchers of FIGGEN hope to accomplish with all their research?

They want inform farmers about the best varieties of figs that are commercially viable and drought resistant to climate change.

The FIGGEN researchers have compiled a list of the 23 fig varieties that did best. A catalog will detail each country’s most tolerant varieties, including the size, juiciness and perishability of the fruit, as well as the tree’s resistance to disease. Catalogs will be distributed to dozens of farmers, nurseries and plant breeders, so that they may choose the most commercially viable and drought-resistant figs to work with in the future. This will potentially enable agriculture across the Mediterranean to adapt to new conditions. Figs have the potential to be one of the most profitable crops in the Mediterranean today.

For the first time, FIGGEN’s work is identifying DNA sequences linked to the resilience of the plant to drought and salinity. “It is not our job to make future hybrids,” explains Giordani. “But by providing the first advanced genetic markers associated to these important traits, we will support fig breeders in their quest to create new varieties of fig even better adapted to climate change and help Mediterranean farmers to survive.”

According to World Bank records, Turkey is the world’s largest exporter of figs. Yet, Tunisia is an important producer on the south side of the Mediterranean. Unlike Turkey, Tunisia has never widely industrialized the process. Over time figs have been selectively bred to adapt to local conditions. The result is that a wide variety of Ficus carica are grown in Tunisia in its different regions.

Ghada Baraket of the University of Tunisa holds a doctorate in fig genetics and heads up the FIGGEN project in Tunisia. Thanks to all the hard work of Tunisian farmers, FIGGEN researchers collected no less than 110 varieties with DNA resistant to drought. “We are all different thanks to our DNA …. Figs are no different—what makes them resistant to drought conditions is coded in their DNA.”

Tunisia’s figs

There are hundreds of varieties of figs in the Mediterranean Basin. They bear different names depending on where they are grown. These figs are known for their exceptional quality because of the valley’s microclimate and the ancestral growing methods of local farmers.

Left A man carries water on his motorbike from the town spring to vegetable and fig gardens in the village of Kesra. Right Since the 17th century CE, a system of tiny canals from mountain springs has carried water to 73 basins that irrigate land in Djebba. Thanks to this collective resource, hundreds of farmers can water their gardens on a rotating basis.

Suspended in the hills of Mount Gorra, the hanging gardens of Djebba el Olia, locally referred to as Ejenna Djebba (from Arabic, meaning gardens of Djebba), a few of the terraced plots exceed one hectare. Figs grow alongside other fruit trees, vegetables and herbs in polyculture, a sustainable system that is based on traditional Berber farming. A network of tiny canals provides water to hundreds of local farmers. These hanging gardens of Djebba el Olia serve as a food resource to the landowners.

FIGGEN participants Faouzi Djebbi and his wife, Latifa, are the proud owners of a 0.7-hectare plot in Djebba el Olia. “All my knowledge about figs, farming and growing food comes from my father, which came from my grandfather, which came from his father,” says Faouzi. Yet he says the changing climate threatens his farming traditions. Springs that flowed at 30 liters per second five years ago have slowed to half that, and some crops are disappearing.

Left Wahchi fig-tree cuttings grow in a nursery in Faouzi Djebbi’s garden in Djebba. He has collected cuttings of 17 of the 24 local varieties of fig and is growing 600 plants to give to fellow farmers to preserve the diversity of local types of fig. Right Djebbi, a school headmaster and fig farmer, poses for a portait in his garden under Mount Gorra.

Question: How have technological advancements have helped fig farmers expand their markets beyond local areas?

Vehicles and new techniques to keep cargo cool have allowed figs to travel farther and command higher prices in distant cities.

Many traditional varieties originating from the Kesra region produce abiadh (white) figs. Over the past 20 years, these older varieties have started to disappear. Until the 1960s, figs could not be transported far as they spoil quickly in the heat, so they were sold locally or kept for home consumption. Vehicles and new techniques to keep cargo cool opened the possibility of selling figs in distant cities. The best figs commanded the highest prices. Zidi figs are large, with a thick skin that keeps the fruit fresh for longer and, depending on their size, farmers can sell Zidis for three times the sum paid for other, smaller abiadh varieties.

There is a catch: To grow lots of fat figs, Zidi trees demand plentiful water. As the land becomes drier, farmers are realizing that reduced fig diversity may threaten their livelihoods. During recent droughts, Zgaya observed that his Zidis sacrificed their fruits to survive. Instead of producing 30 kilograms of figs, a tree was giving perhaps only 7 kilograms, and the fruit was smaller. “However, I have noticed that the fruits of other varieties of fig are less affected by drought,” he says.

Through his contacts, he was astonished to learn that his cuttings would need watering only once when put in the soil to root. While slower growing than local trees, they had resisted drought conditions well. Zgaya was thrilled that they produced a large quantity of high-quality fruit. He now plans to open a fig nursery and pioneer the propagation of this southern variety in Kesra.

Zgaya was lucky to discover the benefit of the Bayoudhi fig on his own. But as the growing season begins, fig farmers, breeders and observers around the Mediterranean will be able to benefit from FIGGEN’s catalogs.

The study identifying the most drought-tolerant fig varieties in Tunisia, Turkey and Spain will be available on its website and in scientific journals this year. FIGGEN’S vital work will help protect farmers’ livelihoods, benefit rural Mediterranean economies and preserve lands that could be lost to cultivation in a hotter, drier climate reality. Back in Kesra, Zgaya takes a fig leaf gently in his hand. “Figs were here before us,” he says. “They belong not to us but to this land, and they will be here long after we are gone. There is no doubt about that.”

Other lessons

Learn the Art of Collaboration via the Art of Tiles

For the Teacher's Desk

With Portuguese tiles as teaching tools, discover how teamwork builds something lasting.

Interpret Tradition in Transition: Remix⟷Culture’s Role in Reviving and Reimagining Folk Music

Media Studies

Art

North Africa

Americas

Investigate how traditional melodies gain new life through Belyamani’s blend of cultural preservation and cutting-edge remix artistry.

How Art Connects

For the Teacher's Desk

Art links everything—cultures, history, even math. Want to hook students? Try teaching through the art that surrounds us with these stories.