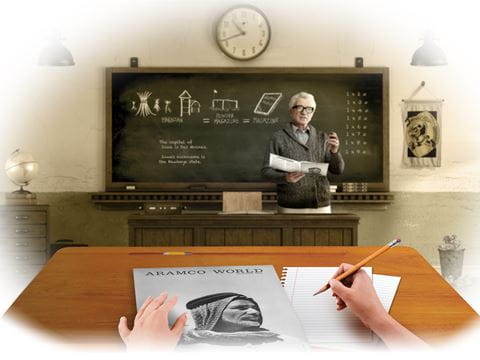

Teach the Art of Collaboration Through the Art of Tiles

For the Teacher's Desk

Written by Lauren Barack and Photographed by Melanie Stegnel

In Brian Betesh's social studies class at Rogers Park Middle School in Danbury, Connecticut, students spend weeks designing a leader capable of addressing the problems that once destabilized the Roman Empire, presenting their proposals to the entire class, or as Betesh calls it, “the Roman council.”

The classroom itself reflects the collaborative nature of the task. Students gather around tables, settle onto couches and spread across beanbags, the room humming with conversation. A computer cannot generate answers to the problem Betesh sets before them, and that limitation is intentional. The work depends instead on sustained exchange—students testing ideas, negotiating differences and shaping their projects collectively.

"When students are learning best, they're learning from each other," says Betesh, Connecticut’s 2026 Teacher of the Year, who has taught at the school for 19 years and returns to the Rome project year after year because collaboration is embedded in its design.

In Brian Betesh's class at Rogers Park Middle School in Danbury, Connecticut, students spend weeks designing a leader capable of addressing problems that once destabilized the Roman Empire by relying on sustained exchanges wherein students test ideas, negotiate differences and shape their own projects collectively among themselves.

"When students are learning best, they're learning from each other."

That emphasis on shared labor mirrors practices found well beyond the classroom, including in the centuries-old tradition of Portuguese tile-making. An AramcoWorld story, “Discover the History of Portuguese Tiles as Artistic Icons,” traces how azulejos emerge through collective effort, from the preparation of clay to glazing and painting, drawing on knowledge refined across cultures and generations.

The Learning Center lessons connected to the story extend those principles into the classroom. Students work together to interpret and visually analyze elements of Portugal’s tile-making tradition, encountering a process in which collaboration is structural rather than supplementary. In doing so, they see how complex outcomes depend on shared effort—an insight that carries across disciplines.

Collaboration occupies a central place in social and emotional learning frameworks and remains closely tied to academic outcomes. More broadly, it shapes how people function beyond school. In fields as diverse as architecture, medicine or entrepreneurship, sustained work increasingly depends on the ability to operate within teams.

Maurice Elias, a professor at Rutgers University, codirector of the Academy for Socio-Emotional Learning and author of a recently released book, Reinvigorating Classroom Climate, situates collaboration as a defining feature of adult life, not simply a classroom strategy.

"In life, collaboration is essential," Elias says. "We're seeing more and more workplaces based on group work, group projects and group management. Being able to collaborate, and especially being able to collaborate with people different from you, is an essential life skill.”

He notes that collaboration draws on a constellation of competencies, including empathy, emotional regulation and shared problem-solving.

In the real world, Miguel Moura, creative director of Cerâmica S. Vicente and a fourth-generation tile painter, depends on collaboration in order for his business to thrive. It is neither metaphor nor theory. It's the foundation that makes the work possible.

Photo credit/Tara Todras-Whitehil

"If I were not able to collaborate with some of my colleagues, I would not accept the work or the commission that they order because I don’t know if I have the capacity to do it all by myself," he says.

His studio recently tackled a 55,000-tile commission for a private residence in Florida, a scale of work that requires coordination across specialties. Moura works with chemists who formulate pigments, craftspeople who produce glazes, fellow painters who share the labor and community members who preserve knowledge of historical tile patterns found across Lisbon. Each contribution carries its own expertise. But together they sustain a living tradition.

"It's easier to share something that belongs to all of us," Moura says of the Portuguese tile heritage.

"It's easier to share something that belongs to all of us."

In the Learning Center lessons, students encounter comparable questions. They consider how symbols and patterns convey meaning and how design choices emerge through dialogue. Educators can extend the exercise by asking students to collaborate on work intended for shared spaces within their school, reflecting the same balance between individual vision and collective execution found in professional practice.

Back in Connecticut, Betesh has broadened collaboration beyond individual assignments through Class Seven, a schoolwide program built around project-based work. Every student participates, with as many as 100 student-led projects unfolding on a given day, he says. Teachers across grade levels support initiatives such as hosting election centers, producing podcasts with local leaders and redesigning school spaces.

"Students are taking on this leadership role but also collaborating with their peers," Betesh explains.

Betesh's sixth grade students adopt collaboration as routine, from which they learn durable work builds from sustained connection, between people, skills and shared purpose.

"Students are taking on this leadership role but also collaborating with their peers," Betesh explains.

Through the program, collaboration becomes routine rather than exceptional. Like the Portuguese tilemakers working across time and specialization, Betesh’s students learn that durable work emerges through sustained connection—between people, skills and shared purpose.

"I look back at my favorite memories in middle school, and they were all with my friends,” he says. “Things that you remember, your project you did with your friends. Not necessarily what you learned but how you learned."

Other lessons

The Legacy of Borchalo Rug-Weaving in Georgia: Explore Cultural Change Through Critical Reading and Design

Art

History

Anthropology

The Caucasus

Analyze efforts to preserve a centuries-old weaving tradition, and connect the Borchalo story to questions of identity, memory and heritage.

Breaking Bread: Using Food As a Teaching Tool

For the Teacher's Desk

Using food as a teaching tool, students widen their global understanding of other cultures while deepening their connection to the world.

Teaching Empathy: Five Classroom Activities From AramcoWorld

For the Teacher's Desk

Help students build empathy and community for the academic year with AramcoWorld’s stories and Learning Center lessons.