The Legacy of Borchalo Rug-Weaving in Georgia: Explore Cultural Change Through Critical Reading and Design

Art

History

Anthropology

The Caucasus

Analyze efforts to preserve a centuries-old weaving tradition, and connect the Borchalo story to questions of identity, memory and heritage.

The following activities and abridged text build off "Are Georgia's Oriental Borchalo Carpets Making a Comeback," written by Robin Forestier-Walker and photographed by Pearly Jacob.

WARM UP

Scan the article's photos and captions to predict its main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Understand why Borchalo rug-making traditions remain endangered by examining the tension between preserving ancestral craftsmanship and adapting to modern methods.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Complete a Cloze paragraph to understand Borchalo weaving traditions and the challenges they face. Then use a graphic organizer to reflect on traditional activities in your own culture that are no longer widely practiced, and why they might be worth preserving.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Understand the process for creating Borchalo rugs by designing your own rug pattern based on the article’s visuals and descriptions.

Directions: As you read, watch for highlighted vocabulary words. Use context clues to guess their meanings, then hover on each word to check if you’re right. After reading, answer the questions at the bottom of the page.

Are Georgia’s Borchalo Carpets Making a Comeback?

The Borchalo rug weaving tradition—unique to ethnic Azerbiajanis in Georgia—almost vanished. But now, a small group of women and supporters work to revive it.

Zemfira Kajarova had already turned 16 when she came, newly married, to Kosalar, an ethnic village in the Kvemo Kartli region of southeastern Georgia, in 1976. Although she arrived from a nearby town and shared Azerbaijani heritage, Kajarova felt like an outsider. She soon discovered the community she began living in cherished its rug-weaving tradition. Kajarova needed to master a new skill. “My mother-in-law taught me how to weave,” she says, smiling at the recollection. “This was how we bonded.”

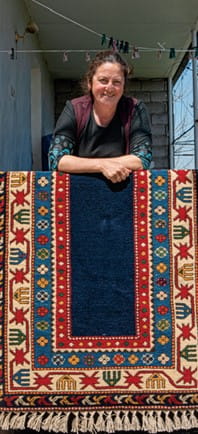

Today weaving continues to unite the older women of Kosalar. They work in their humble homesteads producing rugs celebrated for their quality and design. The soft handwoven wool rugs, known as Borchalo rugs, feature natural dyes extracted from plants and display simple geometric patterns like the tree of life and medallions known as guls. Many patterns carry stamps or tamgas, like sheep. that signify a link to a particular tribe.

Antique Borchalo rugs command high prices at premier auction houses, such as Christie’s. Yet Borchalo rug-weaving faces a bleak future. Every active weaver in the community has passed the age of 50. Unless more young people learn the craft, the tradition could vanish forever. “I’m afraid that this heritage will die,” Kajarova says. “The elderly can’t weave anymore, and the young people don’t want to take this responsibility. They say it’s difficult work.”

Despite these challenges, recognition of the uniqueness of ethnic Azerbaijani rug-weaving in Georgia continues to grow, and with new efforts underway, hope that this tradition can be survive.

History of Tradition

The village of Kosalar lies in southern Georgia at the foothills of a volcanic mountain range. It sits near the town of Marneuli, formerly known as Borchalo, the name the rug takes today.

The origins of the Borchalo remain debated. Some historians trace them to nomads from northern Iran who migrated between 1500 and 1700. Irina Koishoridze, chief curator at the Georgian National Museum, notes that legends and historical sources credit Shah Abbas, a Safavid ruler of Iran, with settling them in the 17th century. Other scholars argue nomadic Turkic tribes introduced their culture to the Caucasus as early as the fourth century CE.

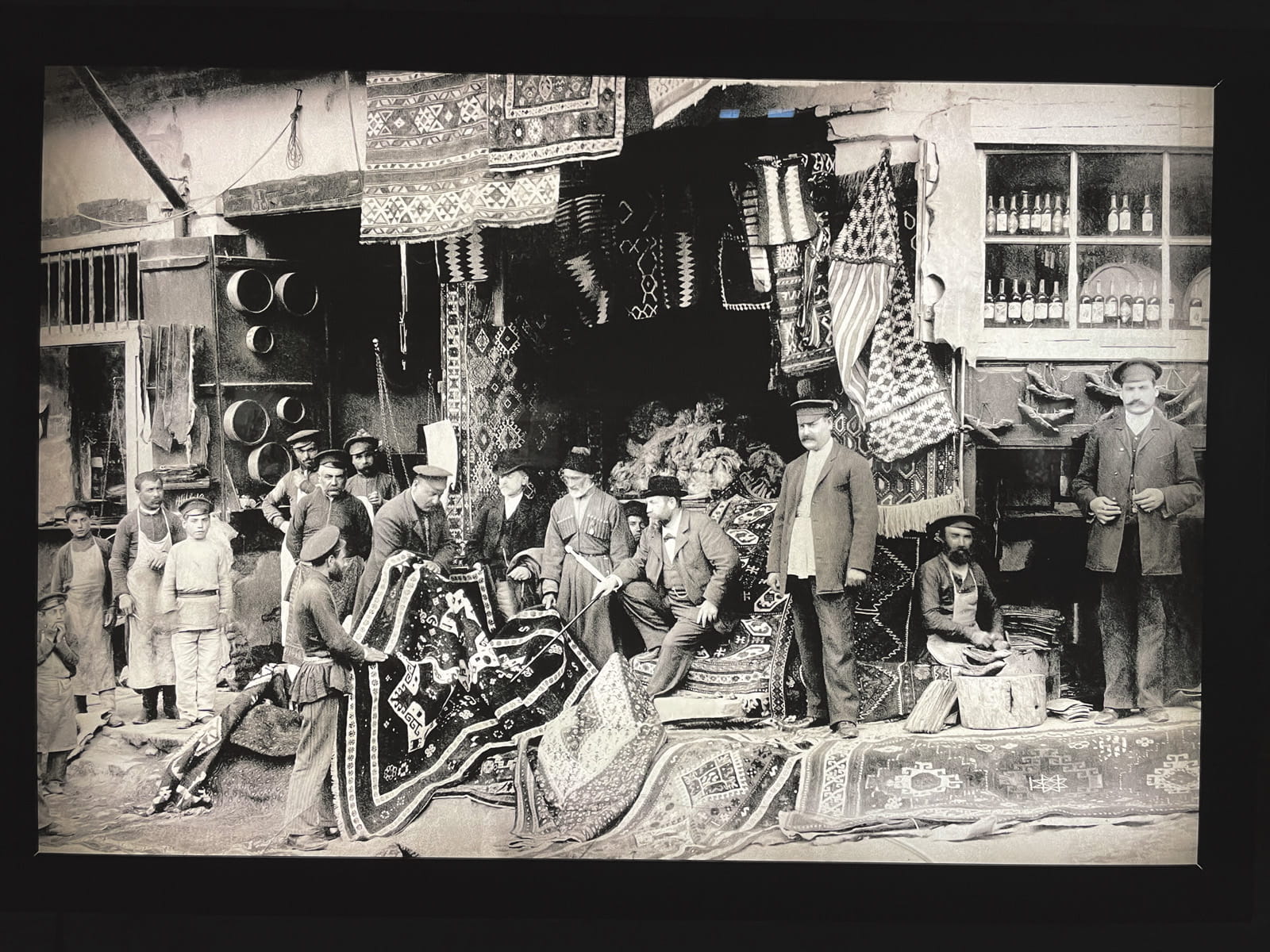

The region late came under Russian imperial control (1721–1917). Recognizing the value of the ruge, the Tsarist government established the Caucasian Handicraft Committee in 1899 to set up weaving centers across the Caucasus for international trade. Steamboats and railways opened the regional rug trade to the wider world, linking Tiflis (as Tbilisi was then known) with fashion influencers in New York and Paris.

During the Soviet era, (1917–1991) economic planners created larger weaving centers to produce rugs in bulk for export. Weavers in Borchalo, however, remain excluded. According to Koshoridze, “They kept their traditions because they never worked for an international market during the Soviet period, and this is why they were so special.”

After the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, Western dealers “discovered” antique Borchalo rugs. They regarded them as fresh and distinctive, with strong, bold and highly individual designs. But then, most looms had fallen silent. The 1990s brought desperate times. The wool industry was broken, and cheap machine-produced rugs left the weavers with little incentive to continue their work.

A few artisans clung to the tradition, using whatever materials they could source, including artificial fibers and chemical dyes. They wove idiosyncratic prayer rugs in vivid colors for local mosques. These rugs carried a folkish charm but lacked the artistry of the 19th century. With no buyers and no institutional support, women weavers struggled to sustain their craft.

Revival

As Azerbaijan’s communities edged toward losing their centuries-old rug-making heritage, a young American Christian missionary, Ryan Smith, saw an opportunity reignite Kosalar’s looms. Smith had fallen in love with the weaving culture during his years in Azerbaijan in the early 2000s. Determined to revive the tradition, he set out to create a market for Borchalo rugs made the traditional way.

Fluent in Azerbaijani, Smith sourced quality wool and natural dyes, found buyers and persuaded retired weavers to reproduce their grandmothers’ designs. He made the effort central to his life. In 2014 he established a local nonprofit organization, reWoven, dedicated to restoring traditional rug-making.

Today, reWoven ships about 30 rugs annually. Larger pieces can cost up to $3,000, and weavers receive competitive prices for their work. Remaining revenue funds community projects. Although Smith tragically died in 2018, his life’s work continues to inspire the community. reWoven has no ambition to become a major business; instead, it focuses on artistic preservation and sustaining a cottage industry.

A New Generation

The greatest challenge lies in recruiting enough weavers to meet growing demand. The Tea house, an education center in Marneuli, offers cultural classes for youth—including rug weaving. Among its students is 14-year-old Maia Ziadalieva. Initially unfamiliar with the tradition, Maia grew to enjoy the process and the calm it brought her. She hopes to master the craft and teach it to others one day.

Twelve students currently practice weaving at the Tea House. Administrators envision more than classes; they aim to establish weaving centers in villages where the tradition still survives. The goal is to inspire young people to view weaving as a business and engage in every step of making and marketing rugs.

The Tea House remains the only place offering formal instruction in Borchalo rug weaving, a craft once passed down exclusively from mother to daughter. With youth at the looms, the art form stands a real chance of enduring.

In Kosalar, women gather to bake loaves of flatbread together in a small bakery—a simple shed housing a stone oven. Their shared labor, whether at the loom or in the fields, sustains a continuity of tradition.

Their exquisite rugs, rooted in the Safavid dynasty, have evolved and adapted over time. Weavers shape them with their own esthetic while responding to international demand. Though the future remains uncertain, the existence of Borchalo rugs no longer hangs by a thread.

Reading Questions:

Question: What is the main challenge facing Borchalo rug weaving today?

Older weavers find it difficult to continue the craft, and younger generations show little interest in taking it up.

Question: During the Russian Empire, how were Borchalo rugs connected to global markets?

They were produced across the Caucasus for export, linking the bazaars of Tiflis (now Tiblisi) to fashion influencers in cities like New York and Paris.

Question: Why did Borchalo weaving traditions remain intact during the Soviet era, unlike other weaving centers?

Soviet planners excluded Borchalo weavers from mass-production centers for the international market, which allowed them to maintain traditional practices.

Question: How does Ryan Smith’s story reflect the challenges and hopes for preserving Borchalo weaving?

Smith’s efforts to source quality materials, create a market and train weavers show that individual passion can revive endangered traditions despite economic and social obstacles.

Question: Why does the author emphasize youth engagement and initiatives like the Tea House at the end of the article?

To highlight that the survival of Borchalo weaving depends on passing the craft to a new generation, ensuring it remains a living tradition rather than a relic.

Other lessons

Learning Center Teaching Tip: Stories That Develop Media Literacy

For the Teacher's Desk

AramcoWorld stories help students learn how media is made, whom it’s for and how meaning is shaped through deliberate choices.

Tracing the History and Geography of Portuguese Tilemaking

Geography

Architecture

Europe

Analyze how culture and technology have changed the ways tiles have been made in Portugal for over 500 years.

Breaking Bread: Using Food As a Teaching Tool

For the Teacher's Desk

Using food as a teaching tool, students widen their global understanding of other cultures while deepening their connection to the world.