Taarab Music: Exploring the History and Cultural Impact in Zanzibar

Art

History

East Africa

Explore taarab’s cultural roots, sound and instruments—then compare its emotional and social impact to music in your own life.

The following activities and abridged text build off "The Heart-Moving Sound of Zanzibar," written by Banning Eyre.

WARM UP

Scan the article’s photos and captions to predict its main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Describe taarab's sound, its historical roots in Zanzibar and the cultural meaning of audience interaction.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Construct a timeline that traces historical and cultural influences shaping taarab music from its origin to today.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Compare traditional taarab instruments and performances to music and instruments from their own lives, identifying both cultural and emotional connections.

Directions: As you read, watch for highlighted vocabulary words. Use context clues to guess their meanings, then hover on each word to check if you’re right. After reading, answer the questions at the bottom of the page.

The Heart-Moving Sound of Zanzibar

A signature of the island’s culture, taarab music blends African, Arab, Indian and European elements

The Indian Ocean Island of Zanzibar is known for its white-sand beaches, fragrant spices and its pivotal role in the East African slave trade. It is also the birthplace of one of this region’s most fascinating and beautiful musical genres, taarab.

The Dhow Countries Music Academy, located in Stone Town, is the first and only music school in Zanzibar. One of Zanzibar’s most-famous taarab groups, Culture Musical Club, recently performed there recently. The room filled with the sounds of traditional and modern instruments, as a chorus made up mostly of female singers, performed in a languid, melodious way, casting warm hypnotic spell. sounds of traditional and modern instruments filled the room. The music’s rolling rhythms, soaring tonalities and plaintive vocal melodies deeply enticed audience members sashaying forward to hand small bills to the singer—a traditional gesture of appreciation.

Taarab music reflects the Zanzibar’s blended culture, bringing together African, Arabic, Indian and European elements. It embodies the region’s complex history of settlement, empire and colonial rule. For more than a century, taarab has been deeply woven into the social fabric of Zanzibar. Though it’s not often heard on radio or television, it continues to thrive at weddings and street celebrations along the Swahili coast of Africa and across the Indian Ocean. In local Swahili, the word taarab means “to move the heart.”

The origins

Taarab is a form of popular folklore music known for its elegance and welcoming spirit. It draws inspiration from Qur’anic recitation and the poetic traditions tied to Islamic culture in East Africa. Despite those elements, taarab is not considered religious music.

For centuries the Swahili coast and Zanzibar were home to Bantu-speaking peoples. In the 15th century, Portuguese traders arrived. They were later driven out in the 17th century by Omani sultans, who established control over Zanzibar and parts of the African coast. This legacy is still reflected today: Zanzibar remains predominantly Muslim, while mainland Tanzania is majority Christian.

One of the last rulers before British colonization, Sultan Barghash bin Said, was a music lover who played a major role in shaping taarab. He brought musicians from Egypt to perform in his court and sent local artists to study there. These musicians returned with qanuns, ouds, violins, and percussion instruments. The music they brought back was quickly indigenized—adapted to local culture with lyrics in Swahili instead of Arabic. It began to incorporate African rhythms and even Western influences like foxtrots, waltzes, and cha-chas.

While classical Arab music tends to be formal, Swahili taarab is communal. It’s social and inclusive, shaped by the diverse cultural history of the region.

One aspect of taarab music is the competition between groups spoken in the lyrics. It started with Siti bint Saad, a woman of slave ancestry who became wildly famous throughout East Africa and beyond. Saad recorded in Bombay (Mumbai today) in India in the late 1920s singing in Swahili. In her songs, she dared to comment on the sultan’s law and later that of the British colonialists and their treatment of women. In modern taarab performances, competition is a major attraction for audiences, with female singers using poetic allegory to playfully skewer one another.

Terminology

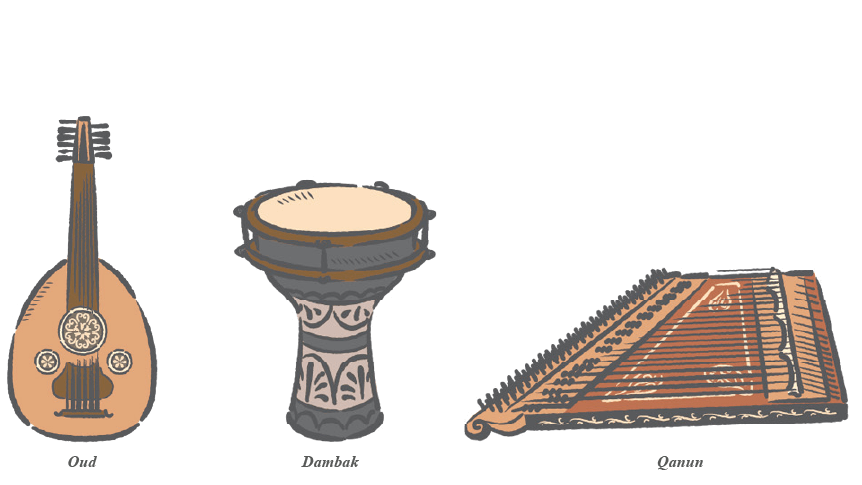

Oud: Lute-like string instrument used predominantly in North Africa. Makes deep, round sounds like that of a classical guitar.

Qanun: Middle Eastern and North African string instrument known as “the Piano of the East” and played on the lap like other zithers, usually in ensemble music. Makes bright, uplifting tones.

Dambak: Single-headed “goblet” drum of the Swahili people of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Rested on the leg and played with both hands. Makes full-bodied tones that emphasize resonance.

Takht: Small ensemble of Egyptian origin, usually no more than five musicians, that plays classical and contemporary Middle Eastern music with these and other melodic and percussion instruments, and sometimes vocalists.

Firqa: Similar to takht but usually numbering eight or more and incorporating Western instruments such as the violin.

Kidumbak: Less refined, upbeat Zanzibari ensemble style performed during celebrations with violin, sanduku (a type of washtub bass), bass and two drums.

Sources: EthnicMusical.com, Oxford University Press, ProducerHive.com, Amar Foundation, Grinnell College Libraries, Music in Africa

*****

Early taarab groups were small, often comprising of just four or five musicians. As the genre grew more popular, groups began to form in Zanzibar neighborhoods. Because people lacked access to instruments, many of these these groups performed with only a vocalist, a single melody instrument—usually a violin—and two dumbak drums, one tuned high and the other low. This set up led to a new musical style called kidumbak, which means “small dumbak.”

Kidumbak ensembles have long served as a training ground for future taarab musicians, helping them develop rhythm, timing and musical collaboration before joining larger orchestras.

The oldest group still performing in Zanzibar is Ikhwani-Safaa, which means “the brotherhood of purity.” It was founded in 1902 during the time of the sultans. The group’s leader, Sheikh Moh’d Ebrahim, was the sultan’s takht, or lead musician. He taught his group to mix Swahili melodies from Kenya with other styles of music.

Over time, taarab groups grew in size. They began to follow the firqa style, a large orchestra format popular in Egyptian movies from the 1930s and 1940s. These firqa groups had many violins, oud, qanun, and drums from both African and Middle Eastern traditions. The musicians came from different backgrounds—Arab, African and Indian—and their performances were loved by many. But the music was mostly played at weddings and private events. It wasn’t recorded or sold.

Culture Musical Club, another famous group, was officially founded in 1958. Before that, many small street groups called kidumbak played music using just a few instruments. By 1970 some of these groups came together to create one big group that focused on music, theater, traditional dance and even acrobatics.

Taarab Today

Taarab music blends different styles, and different regions have their own sound. The Mombasa style uses traditional instruments and stays closer to Arab maqam music, which is based on specific musical scales and moods. The Tanga style, on the other hand, uses electric guitars, keyboards and drum machines instead of acoustic instruments. It also infuses more African-Latin rhythms.

On special part of taarab is how performers connect with the audience. Fans often step out from the crowd to hand small bills to the singer during a favorite song. This is a traditional way of showing appreciation. Sometimes, tipping a singer at a certain moment in the song sends a message to someone special in the audience, making the music feel personal and meaningful.

Taarab lyrics are not always about rivalry and criticism. There are occasions where a song is used to affirm a social relationship, The public airings of romantic intrigues serve both as compelling entertainment and a collective bonding experience for the community.

Back at the Dhow Countries Music Academy in Zanzibar, the Culture Musical Club wrapped up its energetic performance. It concluded with a lively kidumbak set, the ensemble’s percussive grooves anchored in the slap and thump of a standup washtub bass called sanduku.

Reading Questions

Question: In your own words, how would you describe the sound of taarab music?

Answers will vary but should reflect the article’s description—such as its emotional, melodious, rhythmic, or blended sound.

Question:What did Sultan Barghash do to help bring music to the island of Zanzibar?

He invited musicians from Egypt to perform at his court and sent Zanzibari musicians to Egypt to learn music.

Question: Do you think that was a good decision? Why or why not?

During performances, fans sometimes step forward to tip the singer with small bills. The timing of this gesture can send a message to someone in the audience, making the experience personal and emotional.

Question:How is taarab music interactive with its audience?

During performances, fans sometimes step forward to tip the singer with small bills. The timing of this gesture can send a message to someone in the audience, making the experience personal and emotional.

Other lessons

Tracing the History and Geography of Portuguese Tilemaking

Geography

Architecture

Europe

Analyze how culture and technology have changed the ways tiles have been made in Portugal for over 500 years.

Royal Recipes and Everyday Food: Explaining How the Ni'matnāma Shapes Cooking Past and Present

History

South Asia

Discover how the techniques of a 500-year-old royal cookbook endure in today's South Asian kitchens and street stalls.

The Legacy of Borchalo Rug-Weaving in Georgia: Explore Cultural Change Through Critical Reading and Design

Art

History

Anthropology

The Caucasus

Analyze efforts to preserve a centuries-old weaving tradition, and connect the Borchalo story to questions of identity, memory and heritage.