Artist Adel Abidin Explores Historical Memory

Adel Abidin, winner of the fifth edition of the Ithra Art Prize, is making an impression with his intricate tapestry that weaves figurative threads of selective memory to tell the tale of the fragility of history.

The artist’s specially commissioned piece for the Ithra Art Prize is based on the ninth-century Zanj rebellion in Basra, Iraq.

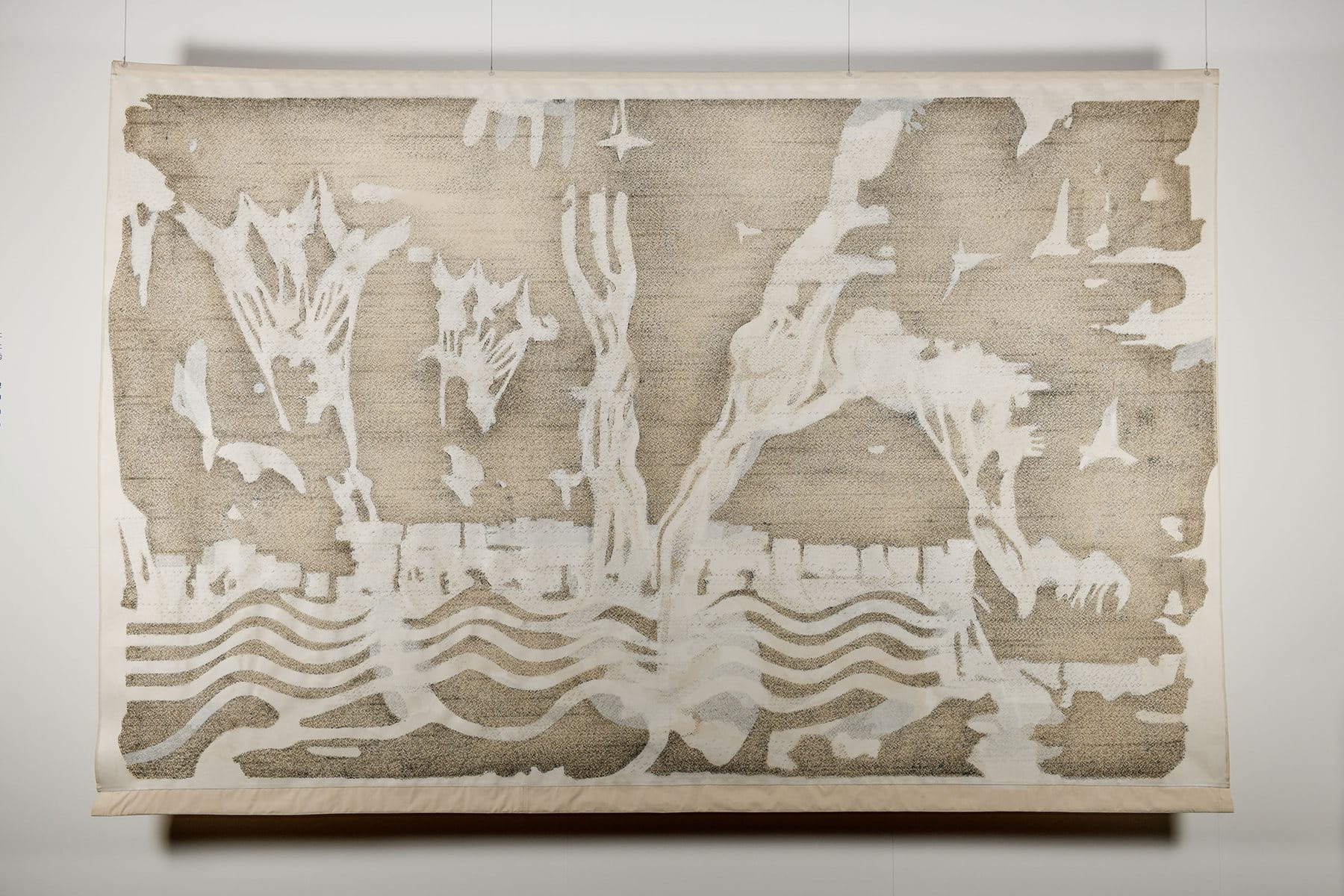

A large cotton-on-canvas work imbued with abstract figures in Japanese paper and ink takes center stage in the Great Hall of the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, also known as Ithra, in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.

The delicate work, akin to an intricate tapestry, is by Helsinki, Finland-based Iraqi artist Adel Abidin, and it is the winner of the fifth edition of the Ithra Art Prize, the largest art grant in the Middle East and North Africa.

Titled Aan in Arabic script, the piece, which is 400 by 250 centimeters (13.3 by 8.3 feet), is made from the literal and figurative threads of selective memory to tell the tale of the fragility of history.

The work, which an independent jury selected from more than 10,000 submissions, explores the relationship among history, memory and identity. Abidin’s piece also investigates the at-once ethereal and powerful aspects of oral storytelling, particularly in the context of Arab history, which some historians have lamented often lacks documentation and is prone to conflicting interpretations.

Born in Baghdad in 1973, Abidin received his bachelor’s degree from the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad in 2000, the same year he left Iraq for Helsinki. Abidin has worked across various artistic mediums, including video, sound-based installations, sculpture and painting. His work is considered bold, edgy and thought-provoking, always made with strong links to his Iraqi homeland and search for identity. Through his work, Abidin, who has been the subject of major art exhibitions worldwide, probes politics, individual expression and mass-media manipulation. His work largely focuses on the differing viewpoints.

Abidin’s winning Ithra Art Prize commission now belongs to the center’s permanent art collection.

The prize was launched in 2017 by Ithra, one year prior to the opening of the center to the public in 2018. The Saudi Aramco-built creative center, like its name, which means “enrichment” in Arabic, focuses on culture, education, new technology and cross-cultural activities. Ithra Museum has five galleries, including one that is dedicated to contemporary Islamic art.

At first glance, viewers of Aan can hardly ascertain its portrayal of the ninth-century Zanj rebellion against the Abbasid caliphate in southern Iraq. The Abbasid was the second of the two great dynasties of the Muslim empire and overthrew the Umayyad caliphate in 750 CE, reigning as the Abbasid caliphate until it was destroyed by the Mongol invasion in 1258 CE.

In 869 CE, the Zanj, largely hailing from southeastern Africa and enslaved in Basra, Iraq, to drain the region’s salt marshes, rebelled against their masters and the caliphate to protest the austere conditions in which they lived.

“History is always told by the victors,” says Abidin. “I am very much interested in history and how history has been written. We never read what the victim has to say.”

In many respects, Aan is a way for Abidin to give voice to the victims of the Zanj rebellion, which continued for 15 years. The revolt grew to involve both slaves and freemen and claimed tens of thousands of lives before it was finally crushed.

“History remains alive and constant, but we often don’t know what is true or fiction,” Abidin says. “Many historical events keep repeating themselves. The Zanj rebellion is a revolution against social injustice like many present rebellions in our world today.”

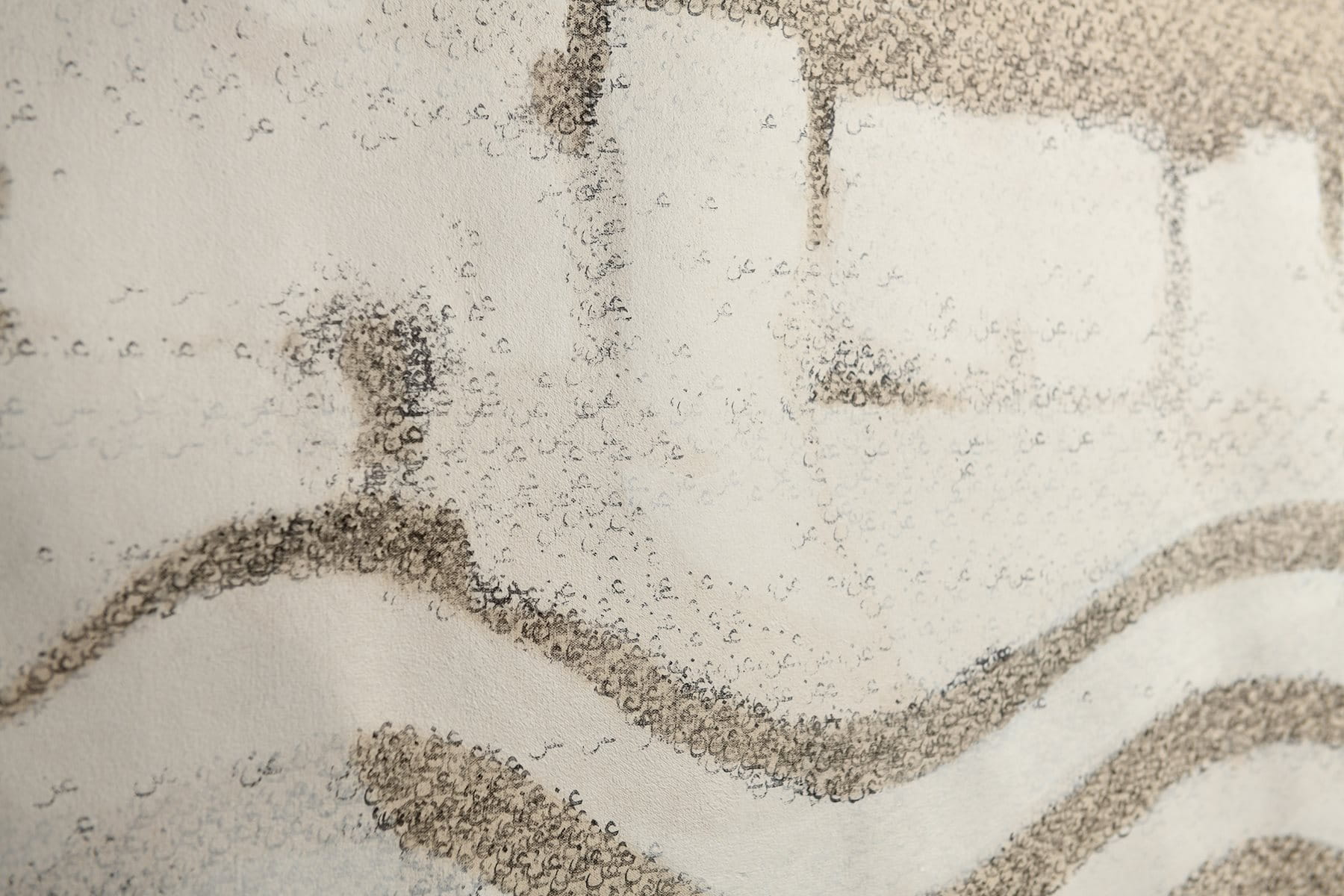

The otherworldly abstract shapes in the mural are made from thin Japanese rice paper and layered with glue and have been made with the repeated stamp of the word “Aan.”

Abidin drew his inspiration from the Japanese philosophy of Ma, emphasizing negative space, often described as a pause in time, an interlude or emptiness in space.

“I returned to traditional techniques, adhering thin Japanese paper to the canvas with starch,” explains Abidin. “This process allowed me to construct layers of information within the negative space, forming a visual narrative and representation of the mythical landscape during the Zanj rebellion in Basra, commencing in 869 AD with the collaboration of the Aan stamps on the canvas.”

He further emphasizes how he aimed to create a work that revealed his own unique perspective on a historical event, recognizing, as he notes, how “much of history relies on oral storytelling.“

"I was interested in creating a work that gives the feeling of a tapestry of history, and the use of rice paper allowed me to accomplish this,” explains Abidin, adding how he would like to continue to learn the technique of working with Japanese rice paper.

The resulting image, laden with movement, reveals a surreal rendering of Basra as well as the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that appear to flow over the city, according to various interpretations that Abidin read of the rebellion. Each stamp presents a different and often contradictory version of the rebellion’s history—the act of its making thus professing the fallacies of historical documentation.

“If you press the stamp hard, it leaves a strong ink imprint, and if you press softly, it leaves only a soft trace,” explains Abidin.

The mural is based on one year of research into the Zanj rebellion and aims to capture the fragility of history and question the accuracy of recorded history, at the same time elevating the voices of overlooked groups or individuals and their own histories.

With Aan, Abidin creates a contemporary work of art that offers an alternative for preserving historical memory—even when the facts surrounding a current or historical event are questioned, as with the Zanj rebellion.

An artwork thus becomes a way of documenting and capturing a lost moment in time and, as Abidin has strived to do, remembering the voices of those who have been defeated and often forgotten.

“A work of art is also a way of storytelling,” explains Abidin. “I believe that art is like a method or a process that we do to argue situations, create arguments, puzzle each other with the aim to make a change.”

In his 2004 one-channel video and sound installation “Cold Interrogation,” the artist explores questions relating to the identity of Arabs, Muslims and Iraqi individuals living in Western societies. “Since I left Iraq in 2000, I have been dealing daily with different questions about my country of origin,” he said at the time.

In a more recent multimedia video work, 2022’s “Musical Manifest,” which was first shown in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Abidin probes the cultural differences he has faced since immigrating to Finland.

Working with themes of identity, power, fear, clichés and uncertainties and misunderstandings in language, the artist questions his identity as one that straddles the Eastern culture of his place of birth and his adopted European homeland during a time of great misunderstanding between the regions.

Music here becomes one of his principal mediums in which to explore the subtleties and innuendos of his two cultural realities.

The idea of revolts across history, giving voice to the victims and the fallibility of history will be explored once again in Abidin’s new show, “The Revolt,” this winter in Helsinki.

The show will be curated by Nat Muller and will reveal an entirely new body of work comprising video, sculptures and drawings.

“In many ways, this show once again draws on the ambiguity not only of history but structural feelings that artworks can convey,” Muller explains. “History is in and by itself something that we always must question—because whose history is it?”

Like the ever-evolving narrative of history itself, the swirling light-colored forms in Aan are meant to both mesmerize and perplex the viewer. As Abidin posits, if history is ambiguous and often shrouded in mystery, then perhaps a work of art holds the key to understanding it with a subjective form of truth, one that is as much based on the facts we know as the facts we have yet to prove and the voices we often have never heard.

You may also be interested in...

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.