Texting Cuneiform

The world’s first palm-sized tablets were made of clay, and they had enough surface for only a few wedge-shaped impressions of a reed stylus. That was how students in Sumer—all boys—learned to write cuneiform. Those who did well could upgrade to bigger clay and go into accounting, law or literature.

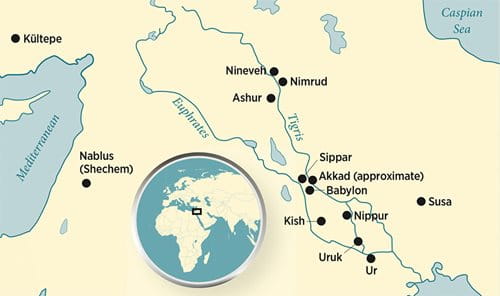

It was more than 100 years ago that a German archeologist named Ernst Sellin began excavations at Tel Balata, an archeological mound near the city of Nablus in Palestine’s West Bank. The mound, or tell, as archeologists call it, proved to be the site of a large Bronze Age city with stone fortifications, monumental gates and a temple with walls five meters thick.

Amid the grander finds were two much smaller ones: a pair of tablets, inscribed with cuneiform. One contained a list of personal names, and it was worn and incomplete. The other was far more intact, and it turned out to be a letter of complaint addressed to the prince of Sikmo (probably Shechem of the Bible), written around 1400 bce by a scribal teacher who had not been paid the grain and oil he was owed for his work. It read, in part: “From three years ago until now thou has had me paid. Is there no grain nor oil nor wine? What is my offence that thou hast not paid?”

Hamdan Taha, former director general of the Palestinian Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage and current dean of research and graduate studies at al-Istiqlal University in Jericho, is also codirector of the Tel Balata Archaeological Park. He says the tablets indicate a flourishing time in early Mesopotamia and point to dynamic relationships between teachers and pupils.

“It shows you how little has changed over the past 3,000 years,” he says, mentioning the challenges students of the time often experienced, from rigorous standards to corporal punishment.

He shares a Sumerian folktale that begins with a boy who shows up late to school and is caned for tardiness. Then he is caned a second time for speaking without permission. Then again for standing when he wasn’t supposed to; yet again for being slow in answering a question and, finally, a last time for answering a question incorrectly. When he arrives home from school, he informs his father—not surprisingly—he wants to quit school, shouting, “I hate the scribal life!” But the boy’s father is clever. He invites the schoolmaster for a sumptuous meal, and the father lavishes gifts upon the teacher. Sated and charmed , the schoolmaster says to the boy, “Young man, because you did not neglect my word, may you reach the pinnacle of the scribal art; may you achieve it completely. You have carried out well the school’s activities. You have become a man of learning.”

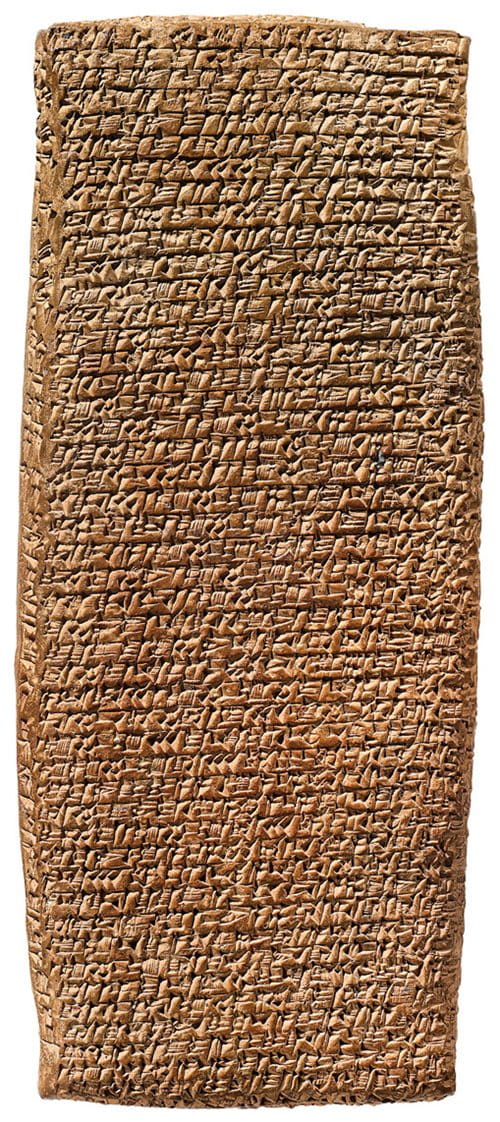

Old Babylonian, ca. 2000–1600 century bce, Mesopotamia

A tablet known as the “School Days” text found in Nippur, Iraq, tells the story of a young school boy and his daily life around the 20th century bce.This humorous tale, probably written by a teacher in about 2000 bce, was deciphered by Samuel Noah Kramer, a 20th-century scholar who interpreted more than 20 such “schoolboy tales.” This apparent popularity, he maintained, suggested the story rose to become part of Mesopotamia’s standard literature, an essential part of scribal education. Such tales from Sumer remain relevant today—none more so than that of the hero-king Gilgamesh, about whom The Epic of Gilgamesh was written in the Akkadian language and today regarded as the earliest-surviving great work of Mesopotamian literature.

Students learned these stories and the other skills of literacy, Taha says, at edubas, the Sumerian word for tablet houses. It was in the edubas that they learned how to read and write using cuneiform, a writing system that originally used pictographs, but over centuries evolved into a system of hundreds of complex, abstract signs that were used, with variations, to write a number of languages, much as nearly the same alphabet can be used for many Western languages. The word cuneiform earns its name from the Latin cuneus (wedge): On the soft clay tablet, the blunt-cut reed used to impress the sign left a wedge-shaped mark.

In the eduba, students first learned to mix clay to just the right consistency for a writing surface. Then they would use water to form a tablet with one slightly convex surface and one flat one. Ideally, the convex side would sit comfortably in the palm of one hand, enabling the pupil to write with the other hand on the flat side. Once the tablets were prepared, the students learned how to cut a reed to use as a stylus. From that they learned the three most basic elements of cuneiform signs—analogous to learning the strokes of a pen in forming a letter: the vertical wedge, the horizontal wedge and the oblique wedge.

After practice, when the student’s wedge-marks reached a suitable level of proficiency, the student would begin to combine the wedges to construct simple signs. Then came sounds represented by the signs. Finally, they learned how to put the signs together to create words, a process that was often assisted by one of the many Sumerian reference lists.

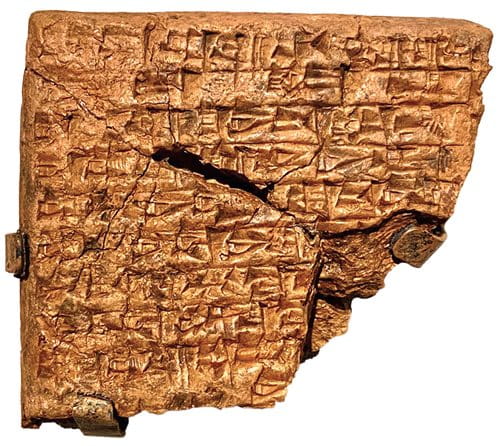

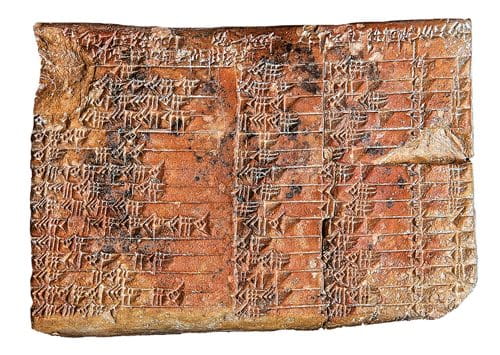

Left: Sumerian, ca. 3200 bce, Mesopotamia / Right: Sumerian, ca. 3100 bce, Mesopotamia

Cuneiform developed from pictographic characters, called proto-cuneiform, such as those that appear on the tablets above, left and right. Such very early writing was most commonly a way of recording economic information: The tablet at top right most likely documents grain distributed by a large temple, and it shows also faint imagery produced by the rolling of a cylinder seal. More than 2,000 years later, the pictograms had become complex signs skillfully impressed into clay.“Scribes wrote lists of names, lists of places, lists of sheep and other animals, lists of stars, lists of gods, lists of objects made from wood and metals, lists of professions and many other lists besides,” writes Jonathan Taylor, a curator of cuneiform artifacts at the British Museum.

“Lists were also used to store other kinds of information. For example, the Babylonians were renowned for their skills as astronomers, doctors and fortune-tellers; knowledge derived from each of these fields was also committed to writing in lists.”

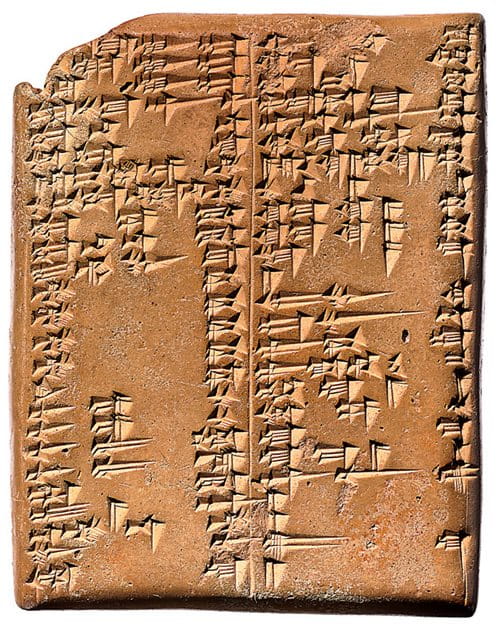

Late Babylonian, ca. 1000 bce, Mesopotamia

This tablet shows cuneiform entries in Sumerian in the left column and Akkadian translations in the right column.All lists descended from the first lexical texts, or word lists, which were created at about the same time cuneiform itself developed in the late fourth millennium bce. Pictographs used in the earliest form of cuneiform, called proto-cuneiform, ran either vertically, from top to bottom on the tablet or—and this was common—in no particular sequence at all. Four hundred proto-cuneiform tablets were first discovered at the Eanna temple in Uruk, now in Iraq, early in the last century, all dating between 3500 and 3000 bce. Most were administrative lists, but a small percentage were lexical lists or tablets for school exercises.

Of the lists available, the information ranged from administrative titles—the king came first—to pottery types and domestic animals, especially sheep. There were no lists of wild animals, nor were there lists of the spoken sounds associated with words: Those kinds of syllabic lists were introduced only in about 2800 bce. Signs for determinatives, or aids for word interpretation, came later still.

By the time of the Third Dynasty of Ur, which endured from about 2112–2004 bce and is called “Ur iii” by archeologists, all the formative elements of cuneiform were present. Ur iii played a special role in the standardization of cuneiform, which supported what became—thanks in part to the power of writing—the Sumerian bureaucracy. Hundreds, if not thousands, of cuneiform tablets were written every day.

“Not only do the records attain their greatest volume in this last blaze of Sumerian glory, but also they become most detailed,” wrote the late Assyriologist and University of Minnesota Regents’ professor of ancient history, Tom Jones, in the 1956 Archaeology magazine article, “Bookkeeping in Ancient Sumer.” “It was not enough, for example, to note the receipt of an ox, but it must be stated whether it was a grain-fed ox, a grass-fed ox, a young ox, an old ox or whether it belonged in any one of a dozen other categories.”

Jones suggested that the specificity Sumerians used in their writing styles were products of necessity in a society that grew increasingly specialized.

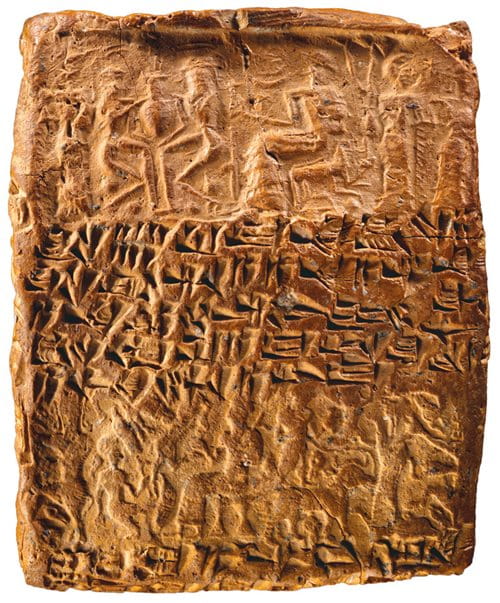

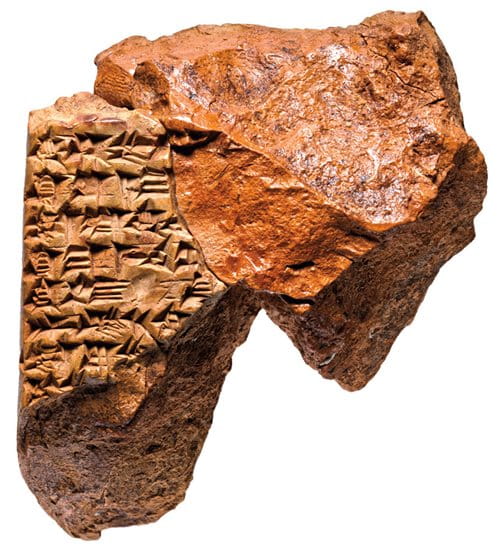

Old Assyrian, ca. 2000–1800 bce, Anatolia

This tablet recorded the repayment of a loan from the settlement of Karriya to that of Ashur-nada. The tablet is impressed with four cylinder seals, which belong to the three witnesses of the transaction: Two of the seals belong to the Old Assyrian stylistic tradition; the third is from an Anatolian-style seal with imagery borrowed from Mesopotamia; the fourth is from a seal belonging to a royal official.“In the first place, ancient Mesopotamia could support a dense population only if the canal system was kept in repair to foster irrigation and prevent floods. This involved the organization and direction of labor; the whole country must be run like an efficient machine,”

he added.

Keeping the country running efficiently was the duty of the king. Sumerians believed their king was chosen by the gods, who met to elect him in the religious city of Nippur. The king was also responsible for caring for his people, which meant he was tasked with defending his kingdom from outside aggression, keeping the irrigation canals open and in good repair, and distributing payment—usually food rations but sometimes silver—to those who accomplished this work.

Though other early economies followed these practices, the Ur iii bureaucracy included far more details in its records. No transaction escaped the attention of the Ur iii scribes, and often transactions were recorded more than once. A single dead sheep of a herd of more than 350,000 may be recorded three different times.

To write the vast number of tablets that an Ur iii economy required, edubas flourished. King Shulgi, who ruled from 2029–1982 bce, placed great emphasis on education, and in addition to many edubas, he built prestigious scribal academies in both Ur and Nippur.

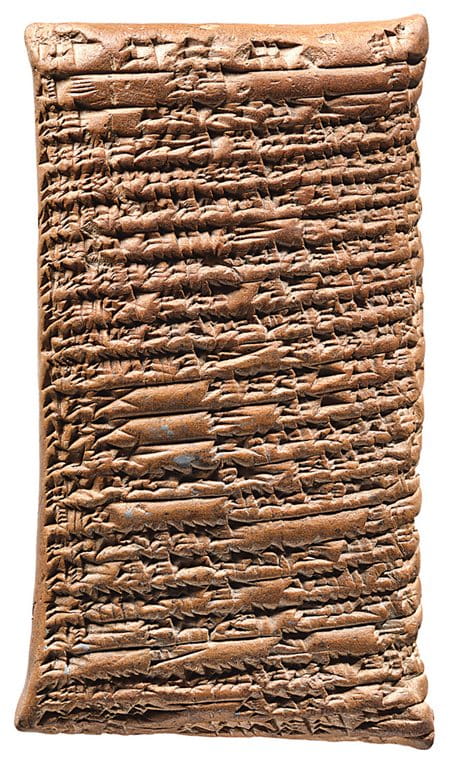

Babylonian, ca. 1700 bce, Mesopotamia

Cuneiform tablets were used to keep records, write poetry and stories, as well as to pursue science and mathematics. This tablet shows a list of mathematical problems, possibly ones that could address architectural questions.According to the eduba literature, these academies were staffed with the ummia, a word that meant teacher, expert or “school father.” The ummia’s assistants, or “big brothers,” were usually older students who did much of the actual instruction. The assistant was known as the man in charge of drawing or “the man in charge of Sumerian” and—remembering the tale of the unfortunate schoolboy—“a man in charge of the whip.”

When Ur fell in 2004 bce, the edubas continued, though by the time of the Old Babylonian period that followed, between 2000–1600 bce, they had evolved into a somewhat different form. The famous academies of Ur iii had been replaced by small schools, usually in private homes grouped together in a scribal quarter. Many were owned by scribes themselves who taught their own sons and one or two other students in their courtyards where, in the light of day, pupils could make tablets and read easily.

Eleanor Robson, a Quondam Fellow of All Souls College in Oxford, has worked extensively on the Nippur scribal quarter. She suggests that a small home in the middle of urban Nippur known now as House F was almost certainly an eduba. Excavators of the area found thousands of fragments of pottery and figurines, as well as gaming boards and tablets, items that, if one leaves aside the electronic capabilities unimaginable to their Sumerian predecessors, could be associated naturally with students today.

Babylonian or Achaemenid, ca. 700–500 bce, Mesopotamia

This small fragmentary tablet contains enough characters to identify it as part of a copy of the flood story, often called Atra-hasis, written in Akkadian. The text, which reads left to right on both sides of the fragment, describes, on the obverse, the noise on earth that led to the decision of the gods to destroy humanity and, on the reverse, the conclusion of the story in which the gods promise to never send another flood.That house, she says, also yielded 1,425 tablet fragments, of which very few were of the administrative kind that make up most of the writing in other tablet collections. In House F, half the tablets contained Sumerian literature, and some 40 percent were school documents.

They show that, as in the Ur iii period, the Babylonian curriculum included mathematics, science, music, reading and writing, all in cuneiform, but with one important difference: For the first time, exercise tablets began to include two columns of signs, one for Sumerian and a second one in the Akkadian language.

Although cuneiform was invented to write Sumerian, by 2000 bce, most Sumerians were speaking Akkadian, an early form of Semitic. This followed the conquests, in 2334 bce, by the Semitic-speaking King Sargon of Akkad, a city in the north. Sargon consolidated an empire stretching from the Mediterranean in the west to the Zagros Mountains (now in Iran) in the east. Akkadian became the official language, and cuneiform was employed to write it.

Old Babylonian, ca. 1600 bce, Mesopotamia

A private letter written by a man named Marduk-mushallim is addressed to his superior to report on the implementation of order from a king, possibly Ammisaduqa of Babylon. Written several decades before the fall of the city, he hints of possible unrest outside of the city and notes the king’s request for increased security around Sippar-Yahrurum, north of Babylon.By the time the Empire of Sargon ended about 2154 bce, Akkadian had become the most widely spoken language. Yet Sumerian remained the language of scholarship. This meant eduba students continued to learn the signs for both.

To master this, students began school at age five or six, completing their studies as young adults. School began at sunrise and ended at sunset. There was little free time. One scribal student complained:

The reckoning of my monthly stay in the tablet house is (as follows):

My days of freedom are three a month.

Its festivals are three days per month. Within it, twenty-four days per month, (is the time of)

my living in the tablet house.They are long days.

Routine school days included lectures in Sumerian as well as cuneiform lessons. Rather like chalkboards, some edubas had sandboxes in which the ummia or his assistant could demonstrate to a group the signs and texts.

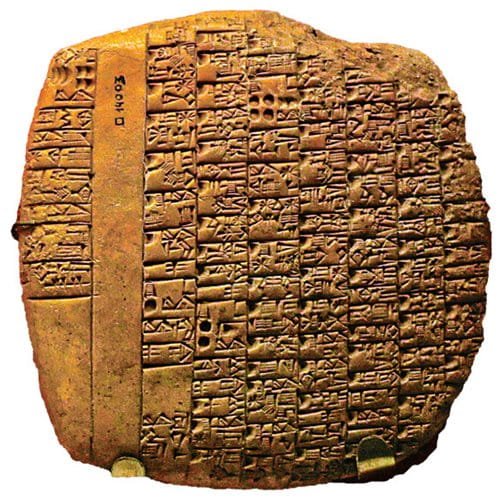

Sumerian, date unknown, Mesopotamia

Many tablets in Sumerian were used to produce lists. This one lists workers belonging to the temple of a goddess in Sumer.As Mark Wilson writes in Education in the Earliest Schools: Cuneiform Manuscripts in the Cotsen Collection, teaching aids such as dictionaries were used, too, often in the form of spindle-mounted clay cylinders that could be rotated to search for the correct sign. Much of the day was devoted to copying, and the ummias would write the daily texts on the back of the tablet, which students would then attempt to copy to the front. The backs of some tablets display notes of teachers giving extra help to pupils who appeared to be falling behind.

Although discipline was strict, there is evidence of humor as well. Wilson reports that one tablet in the Cotsen collection, housed at Princeton University, shows the word “to fart” in a context that would have been almost certain to put a grin on even the most aggrieved student’s face. Some tablets in the Cotsen collection appear well worn and ready for erasure and reuse via a water box. Others show they had been erased and were ready for reuse. As long as the tablet was malleable, only a small amount of water was needed to delete the script by wiping it away. Most tablets, Wilson notes, were likely used many times.

Like schools in many educational systems today, eduba schooling was divided into primary and secondary stages. Gabriella Spada, who has concentrated her studies at the University of Pennsylvania on Sumerian model contracts, explains that secondary students were offered more autonomy and they did not have to rely on a master’s model tablet to copy.

Old Assyrian, ca. 2000–1800 bce, Anatolia

This is the longest-extant Old Assyrian legal text, and it records court testimony describing a dispute between two merchants in Kanesh, in central Anatolia, that was one of the trading settlements of Ashur. In the text, Suen-nada and Ennum-Ashur accuse each other of stealing the contents of a private archive that they each claim to own.However, she adds, “not all the scribes continued onto the advanced curriculum. Whoever intended to specialize in a particular administrative field, such as legal affairs, palace or temple administration, and so on, did not need to widen his knowledge of literary texts.”

Although some scholars believe a basic form of literacy may have been widespread in the general population of the era, there is no doubt that eduba education was limited to the few whose families could afford the tuition. It was also exclusive to boys. Nonetheless, while there is no evidence that girls attended edubas, there were cloisters of women in Sippar and Ur that had female scribes, and temple priestesses, an important position in Sumer, were often literate. Enheduanna, who lived between 2285–2250 bce, was the daughter of Sargon of Akkad and one of the most famous high priestesses in Sumer as well as a popular poet. Among royalty, however, few appear to have been literate.

By the mid-seventh century bce and the time of the reign of Neo-Assyrian King Ashurbanipal, the use of cuneiform was drawing to a close. Aramean traders and invaders from northwest Syria were moving in, bringing their language and writing with them. Between the 11th and eighth centuries bce, Aramean became the lingua franca of the region.

Aramean was very different from Sumerian. It used a 22-letter alphabet. This made it far simpler and far more versatile than the hundreds of complicated characters required to write Sumerian, Akkadian and other cuneiform languages. That made it easier to learn and easier to write. Cuneiform gradually fell out of use. The last known tablets were written in the late first century ce. The Aramean alphabet circulated not only throughout the Middle East but also to Greece, where the first signs for vowels were introduced. Texts—by reed, chisel, quill, pencil, pen or keyboard—changed forever.

You may also be interested in...

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.

Spotlight on Photography: Beneath the Cherry Blossoms in Japan

Arts

Japanese culture reveres the springtime blooms as a symbol of renewal.

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.