Rediscovering Voices and Stories: A Conversation With the Editors of Muslim Women in Britain

When Sariya Cheruvallil-Contractor embraced Islam as a teen, she recognized a divide between her faith and its portrayal in some Western media in the 1990s. Determined to challenge stereotypes, she became a sociologist dedicated to what she sees as Islam’s empowering principles for women.

When Sariya Cheruvallil-Contractor embraced Islam as a teen, she recognized a divide between her faith and its portrayal in some Western media in the 1990s. Determined to challenge stereotypes, she became a sociologist dedicated to what she sees as Islam’s empowering principles for women. For her latest work, Muslim Women in Britain, 1850–1950, she joins her coeditor, historian Jamie Gilham, in uncovering remarkable stories of Muslim women who founded communities, undertook Hajj independently and even reverted (converted) to Islam under great circumstances.

For Cheruvallil-Contractor, this project deeply reflects her mission to showcase the agency and resilience of Muslim women. Gilham, who relishes unpacking the perspectives on 19th-century Muslims, brought to the collaboration his expertise in uncovering overlooked histories. Together, they have created a groundbreaking collection that brings to the forefront the women behind the emergence of British Muslim heritage.

AramcoWorld talked with both editors, who share their journey, the challenges of uncovering hidden histories and why these stories matter now more than ever.

Muslim Women in Britain, 1850-1950: 100 Years of Hidden History - Sariya Cheruvallil-Contractor and Jamie Gilham, eds. Oxford University Press, 2024.

How did you come up with this compilation of Muslim women’s stories?

Sariya: We realized we both wanted to explore the histories of Muslim women in all of these communities that existed in Liverpool, in Woking. It’s almost as if we had to work backwards: We had to look at who was actually doing any work on these communities, and we approached them.

Jamie: I think one of our key points was that we wanted to commission something new rather than to recycle something. For example, Lady Evelyn Cobbold has been well-written about, and we talk about her in the introduction, but we didn’t think there was enough new information about her to warrant a new chapter. She’s an amazing person, but there’s almost nothing new to say about her. Looking at the list, pretty much [for] all of them, a new perspective has been written about. The last chapter [on World War II hero Noor Inayat Khan], for example, was a very original take on somebody who’s been written about extensively. And in terms of Elizabeth Cate’s, a little bit had been written about.

So, we did whittle the contributors down. Some people did drop out, and that was primarily because they couldn’t find enough material to write about the women that they wanted to talk about, which just highlights the paucity of information and archival material about these women.

What was most challenging about pursuing this specific aspect of Muslim history? Jamie, you mentioned, for example, that you faced a scarcity of materials.

Jamie: For me as a historian, that’s a huge problem, and then related to that is that the sources we do have are often written by men, so we have a male [-centric] perspective on things. Also, the history of Islam as a discipline is pretty new, which is exciting, but it makes it all the more difficult when you’re looking at your subjects that are people for whom you have very little primary evidence on the whole.

Sariya: Like Jamie said, resources are usually written by men. It is clearly gendered. For example, Nafeesah Keep, you can actually access transcripts of her talks. So, she did talks at the Liverpool Muslim Institute, and those talks are represented in full in some of the archives that are available, but nevertheless, it is still gendered. What we realized early on is that there is also a class element. Where paperwork, documentation, letters were available—not often but largely—they were from middle- and upper-class backgrounds. There are, of course, exceptions to all of this. I wrote about Mrs. Olive Salomon, a very working-class woman. She was training to be a nurse, met and married her Yemeni husband, and they lived in really deprived conditions. They didn’t have a lot of money. And you know, the argument we make is that when not assured of existential needs, not knowing where your next meal is going to come from, you’re going to be less concerned about preserving your history.

Top: Woking, England, is home to the Shah Jahan Mosque, the United Kingdom’s first purpose-built mosque, which hosted the Muslim Festival in 1917, above.

How did your different academic backgrounds—one in sociology and the other in history—complement or challenge each other in shaping this book?

Sariya: As a sociologist, every time I’d go into Muslim communities here in Britain, I’d get a sense that young people in particular want a sense of their rootedness in British society. I think now around 66 percent of the Muslim community in Britain is of South Asian heritage. Particularly in older generations, there’s a harking back through the history of Islam in South Asia, whereas young people now want to know what Islam is like here [in Britain]. I think my perspective was about ensuring that this work addresses those needs, gives young people, young women in particular, a sense of who Muslims in Britain were 100 years ago.

It was fabulous working with Jamie because he understands history and the historical method. What Jamie also gets is the bigger picture of the history of Islam during that time. So I think we had complementary skills and knowledge.

Which narratives or misconceptions about Muslim women does this book challenge?

Sariya: I think it definitely makes a difference to understandings of Muslim women. Sometimes the stereotypes make us believe that there is only one way of being Muslim and, indeed, being Muslim women.

Jamie: This book as a whole does help build a better picture of British Muslim life in the past but, also more plainly, of Britain’s history and its global history. This is just one tiny piece of that huge jigsaw, but it’s an important piece that has been previously overlooked or underplayed.

In what ways do you think the experiences shared by these women can resonate with other women around the world?

Sariya: This book shows us these women’s vulnerabilities. We tried to humanize these women and show them not as abstract structures. Often history is told by the dominant group, for the dominant group, and Muslim women are nowhere on that hierarchy. So the last line we wrote was we also hope that by showcasing these historical stories of Muslim women who lived in Britain, this book will contribute to understandings about what exactly it means to be British. So, it’s not just about Muslim women’s understandings, but everybody’s understandings of what it is to be British.

Jamie: Another key takeaway for me is these women’s agency and their tenacity, despite—or because of—a quite depressingly consistent level of hostility towards them: hardship, struggle, discrimination. They generally overcame those hurdles. A couple of them probably didn’t maintain their commitment to Islam, and there’s no judgment there at all, but their lives were not easy.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

You may also be interested in...

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.

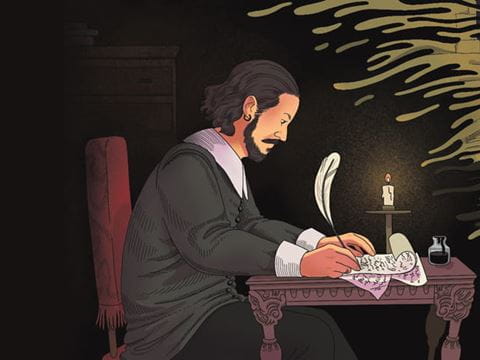

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.