The Alhambras of Latin America

From the 1860s to the 1930s, architects throughout South America and the Caribbean took inspirations from the Islamic design heritage of southern Spain, where the most inspiring building of all proved to be the Alhambra palace.

12 min

Written by Raphael López Guzmán, Rodrigo Gutiérrez Viñuales, et al. Photographs courtesy of Raphael López Guzmán

Neo-Arabic esthetics and architecture have been studied in both Europe and the US but less so in Latin America. The field study carried out here revealed a vast Orientalist heritage throughout the geography of the region encompassing a wide range of architectural types. For the exhibition Alhambras: Arquitectura Neoárabe en Latinoamérica, we evaluated the diversity of designs in institutional, leisure and residential architectures while emphasizing constructions whose origins can be found among immigrants from the Spanish peninsula who copied or drew directly from the Alhambra.

While it shares elements with the more general Orientalist esthetic developed in northern Europe, Latin America’s “Alhambrismo” (“Alhambra-ism”) largely results from the contributions of architects who both trained and traveled in Europe and whose designs, on occasion, reflected the territorial surroundings that inspired them. We must also acknowledge the influences of architectural journals as well as literature such as Washington Irving’s Tales of the Alhambra. In addition, pictorial Orientalism arrived in etchings, illustrated magazines, postcards and even works by renowned European Orientalist painters Genaro Pérez de Villamil and Mariano Fortuny, whose reputations were on the rise also in the capital cities of Latin America at the time. These channels were added to by Latin American travelers and scholars who enjoyed educational travels to Europe.

On many occasions this Latin American heritage is also related to immigrants who sought to incorporate memories of their homeland when they commissioned architects who had traveled to Europe for the construction of their homes.

All these factors contributed to a Latin American Orientalist architecture without rigid requirements but rather adaptive to conditions, personal needs, lifestyles and the local climate. This meant that, on occasion, what featured in an interior in Granada may have appeared on a facade, or what was without color in the walls of the Alhambra may appear as a rich chromaticism typical of the Caribbean. Of course, not all has been conserved over the years. There are significant “absent architectures.” It is to this end that this cataloging of the buildings offers an understanding of the global “romantic” significance of the Alhambra: how its legacy is maintained on the other side of the Atlantic, and how the esthetic of what is known as Alhambrismo was adapted and flourished in a wide range of geographical areas and today forms part of the landscape of Latin American identity.

Spanish Overseas Influences and Islamic Reminiscences

In the 19th century, the celebration of world trade fairs offered a testing ground for architecture. Countries participated by means of pavilions, and the design of these buildings called on local flavors and also borrowed from distant pasts far removed from their national identities.

A predilection for Orientalism led to significant examples of Egyptian and Turkish architecture in the International Exhibition in Paris in 1867 and the Ottoman section in the Vienna exhibition of 1873. The Paris exhibition of 1878 included an Oriental bazaar, and the 1889 exhibition, also in the French capital, featured a market along with Arab-style houses, replicas of streets of Cairo and an Islamic neighborhood.

It was in the 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris, however, that the presence of Moorish architecture had the greatest repercussions. Along with pavilions of obvious Egyptian, Ottoman and Persian inspiration and the construction of the Palais de l’Electricité with its Oriental interior, highlights included “Andalusia in the time of the Moors,” a space that featured elements of the Alhambra, the Sacromonte district of Granada, and the palaces and the Giralda of Seville.

At the time, Spain, and particularly Andalusia, had often been perceived by romantic travelers as exotic, Oriental territories full of bandits and the like. Andalusia, however, also had the unique fortune of offering a rich selection of Islamic architecture.

In this context, it was neo-Arabic architecture that would repeatedly represent the image of Spain in international events, as occurred with the Spanish pavilion in the Brussels exhibition of 1910 and overseas in the clubs and headquarters of Spanish collectives in the Americas. In this sense we could mention buildings such as the Spanish Club of Iquique, Chile, designed and built in 1904 by Miguel Retomano in the Moorish style and featuring ornate, chromatic decor in its interior.

In Buenos Aires in 1912, the architect Enrique Faulkers designed the Spanish Club, the basement of which features the spectacular “Alhambra Room,” murals that depict a 360-degree panoramic vision of Granada. In 1913 in Villa Maria, in Córdoba, Argentina, the Spanish Mutual Benefit Association was erected in a Moorish style. Though built prior to this, the building of the Spanish Association of Panama (1867-1905) was also characterized by its neo-Arabic influences.

Another reference to the link between Spanish and neo-Arabic architectural styles can be found in the Moorish pavilion donated by the Spanish community to Peru in 1921 for the country’s centennial. On display in the exhibition grounds and standing out on account of its enormous horseshoe arch with bichromatic decoration in the manner of the arches of the Great Mosque in Córdoba, it was rebuilt in 2000. In 1923, during the centennial celebrations in Tandil, in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, the Spanish community donated a Moorish castle to the town, erecting it at the highest point of Independence Park, a kilometer from the fort that represented the earliest establishment of the town.

Another area in which Spanish-style architecture featured prominently was in bullrings. Among these, the pioneering reference was the bullring constructed in Madrid by Emilio Rodríguez Ayuso and Lorenzo Álvarez Capra in 1874, a year after the latter had designed the Spanish pavilion for the international exhibition in Vienna. This arena, classified as Neo-Mudéjar and built in red brick, influenced other outstanding Latin American constructions, such as the Plaza San Carlos in Uruguay, inaugurated in 1909, and the Plaza Santa Maria in Bogota, which opened in 1931, and others. We can also find notable examples in Venezuela, top of the list being the Nuevo Circo bullring in Caracas (1919) and the arena in Maracay (1933), the work of Carlos Raúl Villanueva, the premier modern architect in the country.

The Prestige of Institutional Orientalism

Despite never having prevailed in the field, institutional architecture has also employed Oriental forms and decorative models, for cultural or service-related purposes, or as a means of featuring designs related to the exercise of power. While the repertoire of institutional buildings cannot bear comparison with the number of preserved examples of country estates and mansions, the unique nature of many of them shows that the predilection for mainly Alhambresque stylings was not exclusively associated with privately funded projects.

From the latter half of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century, architects incorporated these exotic, foreign dialects into commissions that, in some cases, ended up becoming symbols of national identity.

The fascination for the Alhambra palace in Granada, the Giralda Tower in Seville, the Mezquita, or Great Mosque, in Córdoba and other Oriental gems, not to mention the strong influence exerted by Owen Jones’ Alhambra Court, led to the proliferation of Moorish-style pavilions in world trade fairs also in North and South America. One of the first to be produced on American soil was presented by Brazil for the International Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876, though far more significant was the project known as the Kiosk of Santa Maria de la Ribera, the pavilion representing Mexico in the World Cotton and Industry Centennial Exhibition held in New Orleans in 1884. According to Elisa García-Barragán, the design, which was the work of José Ramón Ibarrola, may be considered the most lavish example of Mexican Orientalism. While Ibarrola did not visit Europe, his friendship with Eduardo Tamariz, the maestro par excellence of neo-Arabic architecture in Mexico, coupled with his knowledge of earlier Moorish-style pavilions, acted as sources of inspiration. The amalgam of incorporated elements, which included stepped battlements, lobed arches, cube capitals and brilliant, rich colors, were bolstered by the modern nature of the materials used and led to the construction being known in the day as “The Mexican Alhambra.”

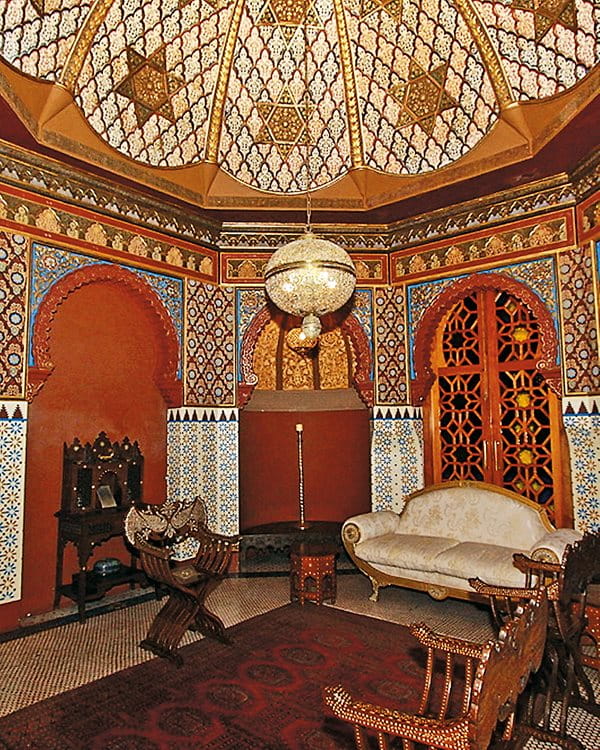

At times Orientalism was applied to reduced interior areas in an exact likeness to specific areas of the Alhambra, while on other occasions this architectural style was reserved for the exteriors of the buildings, where bay windows and decorative elements emulated the Moorish style. In the case of the former, we can highlight the “Salón Morisco” or Moorish Room of Mexico’s National Palace, or the Palacio Catete in Rio de Janeiro, which passed from a private residence to become the seat of the Government of the Republic from 1897 to 1960. Somewhat more recent in its construction is what is known as the “Moorish garden” in Costa Rica’s Legislative Assembly building.

In the case of the latter we can cite the High Court of Military Justice in Lima, Peru, where clear Moorish influences can be seen, not only through the use of specific architectural elements but rather for the fact that the construction materials simulate the ashlars of the Great Mosque in Córdoba. In Campinas, Brazil, in 1908, the Municipal Market was constructed on the orders of architect Francisco de Paula Ramos de Azevedo, who used the typical red-and-white bichromatic coloring of Córdoban architecture on both the walls and the horseshoe arches that define the space.

Likewise, what is known as the National Building in Neiva, Colombia, features paired horseshoe arches and a tower capped with a bulbous dome. Other buildings first served other purposes before being appropriated for government spaces, as is the case with the State Congress in Puebla, Mexico. This is housed in one of the more emblematic neo-Arabic buildings in the city, a building that was originally the headquarters of the artistic-philharmonic society La Purísima Concepción. It features a courtyard designed in 1883 by Eduardo Tamariz, the lower part of which is inspired by the esthetic of the Alhambra. Walls featuring tiled baseboards and plasterwork give way to lobed arches that serve as access routes to other spaces.

Neither were public buildings safe from Alhambra-style imitation, one example being the Palacio de las Garzas, or Herons’ Palace, the residence of the President of the Republic of Panama. One of the finest rooms is the Smokers’ Room, located in the residential area of the building, which not only reflects Orientalism in its decoration but also in the furnishing. Religious architecture also succumbed to Arabic influences, including the Chapel of Saint Joseph, the work of architect Cecil Luis Long and built in 1893 inside the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of the Light, in Leon, Mexico. Spatially like a domed qubba, neo-Arabic influences pervade the interior decor. Equally surprising is the church of Our Lady of the Rosary in San Luis, Argentina, which was built in 1935. The exterior is an attempt to replicate the entrance to the Great Mosque in Córdoba, with a large, horseshoe arch protected by twin towers in the style of the Giralda, in Seville.

Orientalism for Leisure

Early-20th-century Europe, with its romantic personality and propensity for escapism that marked its educated classes, understood that one of the most suitable architectural styles for the construction of leisure venues was the neo-Arabic style. This was also the case in the Americas.

At the time, architectural designs revealed the interests of a no less dream-obsessed Latin American society. A fine example of this is the Concha-Cazotte husband-and-wife team, one of the most acclaimed couples in turn-of-the-century Chile, who converted their Orientalist palace in Santiago into one of the most-renowned bourgeois scenes in the city.

Theaters, cinemas and other entertainment venues soon adopted the same language, and Nasrid plasterwork, bulbous domes and Persian iwans were not long in appearing, examples of this being the theaters Juarez in Guanajuato, San Martin in Buenos Aires, Alhambra in Havana and the cinemas Alcázar and Palacio in Montevideo and Rio de Janeiro respectively.

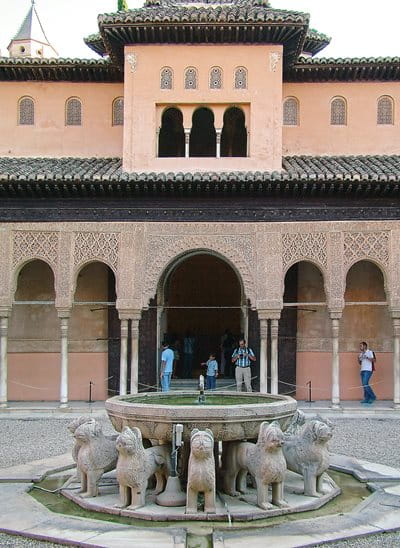

This “exotic impulse” also manifested itself in the skating rink in the Vista Alegre neighborhood in Santiago, Cuba; in the race track in Lima; in the pavilion of the Ateneo Uruguayo in Montevideo—the most notable example of the new style in the country and now unfortunately disappeared—and in one of the buildings in the Republic (or City) of Children in La Plata, Argentina. Perhaps the most Alhambresque of all these projects was the unfinished theater-restaurant conceived by Jorge Soto Acebal in 1915, in which patrons could watch the show while dining in what was almost an exact replica of the Alhambra’s Courtyard of the Lions.

Another use for neo-Arabic architecture pays tribute to the beneficial effects of water. In Argentina two examples include the Natatorio Juan Perón (swimming baths) in Salta, built in 1940, and the hydrotherapy center known as the Arabian Palace in Buenos Aires. In the Mexican town of San Luis Potosí, the San José Public Baths relate in terms of both the type of building and the architectural style.

Another aspect in which the Alhambra exerted influence was in gardens, the truth being that the landscape and vegetation of the Generalife gardens in the Alhambra was copied just as often as the architecture of the palaces. In the La Tropical gardens in Cuba, not only did they imitate the columns, arches and tiles of the Alhambra in the main building, but also the adjoining gardens were organized around fountains and irrigation channels like those used in the palace.

In Argentina the same concept underlies the residences of Enrique Larreta, both the house-museum in Buenos Aires, which today houses the Museum of Spanish Art, and El Acelain, which is inspired by the Main Canal Courtyard of the Alhambra. Another unique example is the Granada Courtyard of the Art Museum in Ponce, Puerto Rico (1964), in which René Taylor, the first director of the institution, on his return from a visit to Granada, designed a courtyard inspired by the Alhambra’s adjoining garden, the Generalife.

Living in Dreamland

As was the case in Europe, in Latin American architecture during the latter half of the 19th century, eclecticism began to allow for both the fusion of styles and the appearance of notably hybrid historicist forms, in particular in reference to exotic private residences. These fantasy homes served individuals as a means of social distinction particularly in the 1920s and ’30s, though earlier and later examples are still to be found. The upper echelons and new American bourgeoisie lost no time in adopting these architectural daydreams as a means of portraying an external image of eccentric wellbeing.

The first Moorish-style building in Latin America dates to 1862 and is known as the “Palace of the Alhambra,” the work of architect Manual Aldunate. It is in Santiago, Chile, and today it houses the National Fine Arts Association.

It is interesting to observe this type of construction in countries where Arab traditions are even less prominent, such as Bolivia, where the Castillo de la Glorieta (1893-1897), just a few kilometers from Sucre, offer a burst of oriental fantasy in the very heart of the Andes. Not all these residences echoed the Moorish style throughout, on occasion this being reserved for just some of the rooms, as is the case with the Palacio Portales (1912-1927) in Cochabamba, Bolivia, which is the work of Simón Patiño, a businessman known as “The King of Tin,” which features a billiards room in the Moorish style.

In the Río de la Plata region of Argentina, we can highlight the courtyard of the Arana residence, which originally housed a replica of the Fountain of the Lions in the Alhambra palace in Granada. It was constructed between 1889 and 1891 by the Spanish sculptor Ángel Pérez Muñoz, based on an idea brought from Europe by the founder of the city, Dr. Dardo Rocha. In Montevideo, Uruguay, we can highlight La Quinta de Tomás Eastman (1880), also known as La Quinta de las Rosas (quinta means country home or estate), as well as some private residences in the city center.

While we can find examples of notable private residences in the neo-Arabic style throughout virtually the entire continent, only a handful of which have been selected as examples here, it is in the Caribbean region where these are most abundant. As was customary at the time, these residences were widely dispersed, having been conceived as iconic, unique buildings. In Puerto Rico we can point out the home of Enrique Calimano in Guayama, entrusted to architect Pedro Adolfo de Castro in 1928, who also incorporated a replica of the Fountain of the Lions in the Alhambra palace that is identical to the one built years later in the Casa de España in San Juan.

The most impressive example of Moorish architecture in the Caribbean can be found in Punta Gorda, a slice of land belonging to the town of Cienfuegos, Cuba, and housing a palace that was entrusted to the architect Pablo Donato by Asturian-born Aciscio del Valle y Blanco and built between 1913 and 1917. The building is noted for a marked eclecticism that manifests itself in the provenance of the materials used, which includes Carrara marble, Italian alabaster, ceramics from Venice and Granada, Spanish ironwork, mosaics from Talavera, European glasswork and Cuban mahogany.

In terms of residential neighborhoods, the Caribbean is also where we find ensembles that, in the main, are noted for Moorish influences, such as Lutgardita in the Cuban district of Rancho Boyeros. In Puerto Rico the houses built using reinforced concrete in the Bayola district of Santurce are worthy of note, as are those of the Gazcue district in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and the Moorish-style houses of the Manga district of Cartagena de Indias, Colombia. Other localized sectors display similar characteristics, including the notable presence of neo-Arabic architecture, such as the San Francisco neighborhood of Puebla, Mexico.

You may also be interested in...

Meet Sculptor Marie Khouri, Who Turns Arabic Calligraphy Into 3D Art

Arts

Vancouver-based artist Marie Khouri turns Arabic calligraphy into a 3D examination of love in Baheb, on view at the Arab World Institute in Paris.

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

Handmade, Ever Relevant: Ithra Show Honors Timeless Craftsmanship

Arts

“In Praise of the Artisan,” an exhibition at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, aims to showcase Islamic arts-and-crafts heritage and inspire the next generation to keep traditions alive.